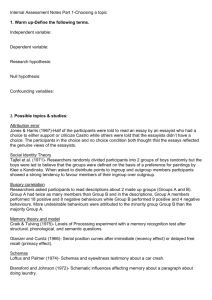

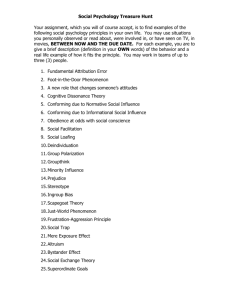

Ingroup Identification as the Inclusion of Ingroup in the Self

advertisement