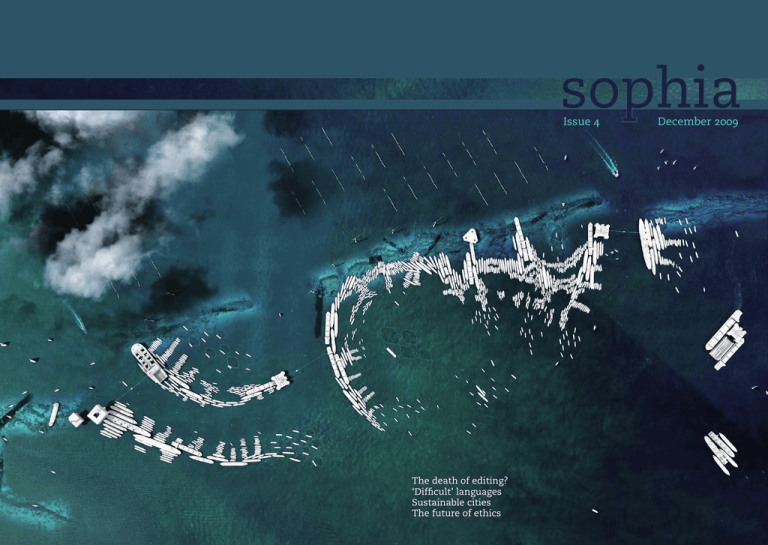

sophia December 2009 Issue 4 The death of editing?

advertisement