The Bio-economics of Sea Turtle Use in Mexico: History of... Lepidochelys olivacea

advertisement

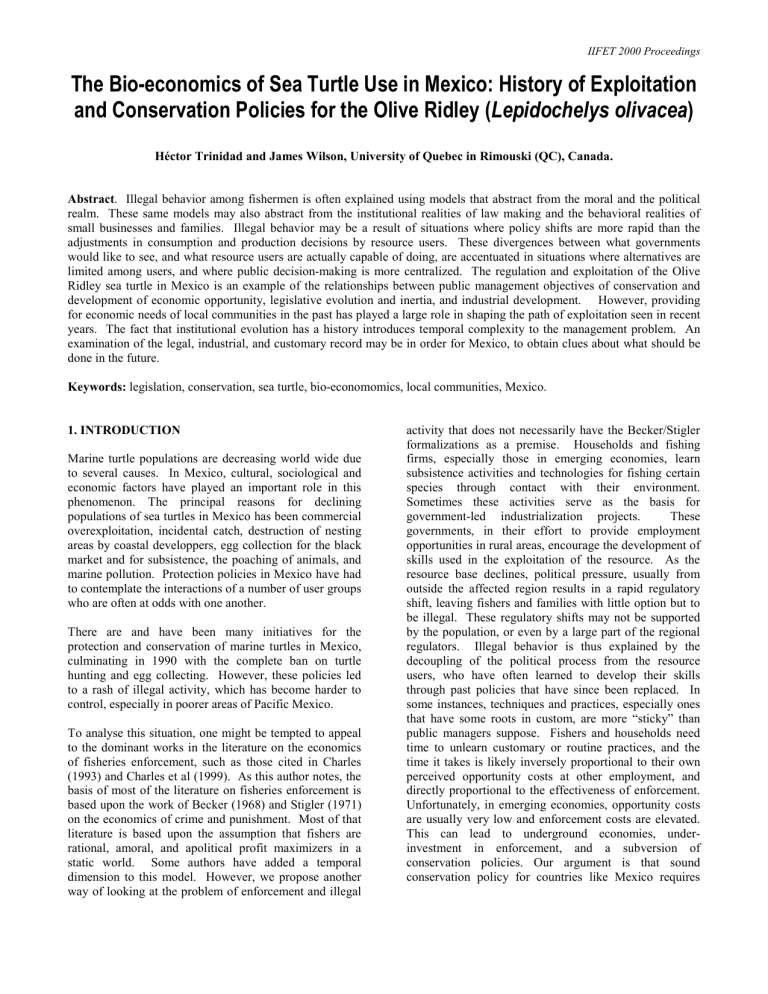

IIFET 2000 Proceedings The Bio-economics of Sea Turtle Use in Mexico: History of Exploitation and Conservation Policies for the Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) Héctor Trinidad and James Wilson, University of Quebec in Rimouski (QC), Canada. Abstract. Illegal behavior among fishermen is often explained using models that abstract from the moral and the political realm. These same models may also abstract from the institutional realities of law making and the behavioral realities of small businesses and families. Illegal behavior may be a result of situations where policy shifts are more rapid than the adjustments in consumption and production decisions by resource users. These divergences between what governments would like to see, and what resource users are actually capable of doing, are accentuated in situations where alternatives are limited among users, and where public decision-making is more centralized. The regulation and exploitation of the Olive Ridley sea turtle in Mexico is an example of the relationships between public management objectives of conservation and development of economic opportunity, legislative evolution and inertia, and industrial development. However, providing for economic needs of local communities in the past has played a large role in shaping the path of exploitation seen in recent years. The fact that institutional evolution has a history introduces temporal complexity to the management problem. An examination of the legal, industrial, and customary record may be in order for Mexico, to obtain clues about what should be done in the future. Keywords: legislation, conservation, sea turtle, bio-economomics, local communities, Mexico. 1. INTRODUCTION Marine turtle populations are decreasing world wide due to several causes. In Mexico, cultural, sociological and economic factors have played an important role in this phenomenon. The principal reasons for declining populations of sea turtles in Mexico has been commercial overexploitation, incidental catch, destruction of nesting areas by coastal developpers, egg collection for the black market and for subsistence, the poaching of animals, and marine pollution. Protection policies in Mexico have had to contemplate the interactions of a number of user groups who are often at odds with one another. There are and have been many initiatives for the protection and conservation of marine turtles in Mexico, culminating in 1990 with the complete ban on turtle hunting and egg collecting. However, these policies led to a rash of illegal activity, which has become harder to control, especially in poorer areas of Pacific Mexico. To analyse this situation, one might be tempted to appeal to the dominant works in the literature on the economics of fisheries enforcement, such as those cited in Charles (1993) and Charles et al (1999). As this author notes, the basis of most of the literature on fisheries enforcement is based upon the work of Becker (1968) and Stigler (1971) on the economics of crime and punishment. Most of that literature is based upon the assumption that fishers are rational, amoral, and apolitical profit maximizers in a static world. Some authors have added a temporal dimension to this model. However, we propose another way of looking at the problem of enforcement and illegal activity that does not necessarily have the Becker/Stigler formalizations as a premise. Households and fishing firms, especially those in emerging economies, learn subsistence activities and technologies for fishing certain species through contact with their environment. Sometimes these activities serve as the basis for government-led industrialization projects. These governments, in their effort to provide employment opportunities in rural areas, encourage the development of skills used in the exploitation of the resource. As the resource base declines, political pressure, usually from outside the affected region results in a rapid regulatory shift, leaving fishers and families with little option but to be illegal. These regulatory shifts may not be supported by the population, or even by a large part of the regional regulators. Illegal behavior is thus explained by the decoupling of the political process from the resource users, who have often learned to develop their skills through past policies that have since been replaced. In some instances, techniques and practices, especially ones that have some roots in custom, are more “sticky” than public managers suppose. Fishers and households need time to unlearn customary or routine practices, and the time it takes is likely inversely proportional to their own perceived opportunity costs at other employment, and directly proportional to the effectiveness of enforcement. Unfortunately, in emerging economies, opportunity costs are usually very low and enforcement costs are elevated. This can lead to underground economies, underinvestment in enforcement, and a subversion of conservation policies. Our argument is that sound conservation policy for countries like Mexico requires IIFET 2000 Proceedings conservation and the improvement of living conditions of rural populations, and the prevention of the destruction of these goods. These articles provide important legislation defining the relationship between economic activities and environmental protection measures. The earliest effort at marine turtle protection is the Fishery Regulation of February 17, 1927. Article 97 prohibited collecting turtle eggs and the destruction of nests (INP 1990, Márquez 1996a). In 1929, closed seasons and minimum sizes were in force for several species of marine and river turtles. Prohibitions on collecting turtle eggs and nest destruction was reaffirmed in the National Decree of February 14 and in its reforms enacted in October (Instituto Nacional de la Pesca (INP), 1990). These measures continued in the Decree of April 10, 1930; in the Fishery Regulation of January 20, 1933; and in the decree of May 7, 1945. first that we understand the economic history of the management failure. This is an historical account of Mexico’s attempt to manage marine turtles, with reference to the Olive Ridly turtle population in the State of Ouaxaca. A brief discussion of the resource is presented. In the next section, we discuss the legislative history of Mexico. In Section 3, we discuss the industrial evolution of turtle exploitation. We finish the article with recent management problems caused by the ban on turtle hunts and egg harvests. We argue that these problems are holdovers from past policies. The paper concludes with a discussion of likely policies to stabilize resource use. Márquez (1996a) cites eight species and three subspecies of marine turtles in the world oceans. Of these eleven different varieties of sea turtles, ten are present in Mexico. Among the species of sea turtles, the olive ridley exhibits rapid growth rates. Adults measure between 51 cm and 78 cm with an average of 67,6 cm (n=844) for both sexes, and with a weight of 33 to 43.4 Kg (Márquez 1977, 1996a). The average clutch size of the olive ridley is 110 eggs (Márquez 1996a). Its geographic distribution covers practically the entire tropical ocean in the Northern Hemisphere (Márquez 1990, 1996a). This species of marine turtle is believed to have the largest population in the world at this time (Márquez 1990). At present, some of the principal remaining rookeries are Gahirmatha, in India (Pandav 1999); Nancite and Ostional in Costa Rica, and Escobilla in Mexico (Márquez 1990). Since 1960, the protection, conservation and research efforts of the Fishery authorities increased, in response to development of the industry. The Federal Government also acted to protect marine turtle species from overexploitation and poaching. In 1962 it formed the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones BiológicoPesqueras (National Institute of Fishery and Biological Investigations). The first Program of Research and Protection of Marine Turtles was started, with initial missions in Cozumel and Isla Mujeres, Quintana Roo (INP 1990). In this year, the total capture of marine turtles was 1,400 tons (Figure 1) (INP 1990). During this time, marine turtle population dynamics became better known. Field research located nesting beaches, and obtained data of biological interest. The Institute published studies of marine turtles on a regular basis starting in 1964 (Márquez 1977). In 1965, turtle campsites were installed at Boca de Pascuales and Boca de Apiza in the Pacific coast of Colima, and Barra de Calabazas in the Gulf of Mexico coast of Tamaulipas (INP 1990). The catch in 1965 was 2,200 tons (Figure 1). The olive ridley has a survival strategy known as arribazón (Márquez 1990). These mass aggregations occur at specific periods during the nesting season, especially in the last quarter of the moon (Peñaflores 1988, Márquez et al. 1997). Olive ridley nesting areas in Mexico cover the entire Pacific coast (Márquez 1996a, Briseño et al. 1999) from Baja California to Chiapas. Their migratory routes in Mexico reveal that they are based upon feeding and nesting patterns. Briseño et al. (1999) concludes that the East Pacific olive ridley nests on more than one beach, and that the Escobilla population probably contributes to the gene flux in other rookeries. During the 1966-1967 period, Federal legislation reiterated prohibitions on collection, commerce, and destruction of turtle eggs, as well as the capture of females during nesting (Márquez et al. 1992). Three more turtle campsites were created at Mismaloya in Jalisco, Piedra de Tlalcoyunque in Guerrero and Escobilla in Oaxaca. In 1968, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry through the General Direction of Fisheries and Related Industries imposed conditions on permit holders who hunted turtles. These included conservation measures in rookeries, the banning of on-board slaughter and processing, and the application of fines and permit cancellations for offenders (Secretaría de Industria y Comercio 1968). Even with these attempts at regulation, the catch increased, and in this same year the landings reached a maximum of 15,000 tons (300,000 turtles). 2. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY The Mexican Federal Government first took measures with respect to environmental goods and services in the 1917 Mexican Political Constitution, presently in force. Article 25 calls for environmental protection by declaring that national development policies must support economic growth, but must also protect the public interest and preserve the environment. Article 27 defines the Federal role in the distribution of natural resources and environmental goods for the social benefit, their 2 IIFET 2000 Proceedings middle and late 1980’s. In this same year, Rancho Nuevo became the first reserve for the protection of the Kemp’s Ridley turtle in Tamaulipas coast (INP 1990, SEPESCA 1990, Márquez et al. 1992). The capture of the hawksbill sea turtle stopped in 1979 since no quota was authorized for that species (SEPESCA 1990). Even so, hawksbill sea turtle products were regularly found in tourist locations like Cancun, Cozumel, Acapulco, and Puerto Vallarta. This was more than the 50% of world catch in that year (Márquez 1977, 1996a, 1996b; Márquez et al. 1992). The olive ridley had important populations in the Mexican Pacific. Due to this relative abundance, the fishery turned to this species (Márquez et al. 1992, Márquez 1996a). From this year to the beginning of the 1970’s, landings declined by more than 50%. In 1971, the first fishery legislation specifically aimed at the sea turtle fishery appeared in the Official Federation Journal (Secretaria de Pesca (SEPESCA), 1992). These initial regulations dealt with the leatherback and the Kemp’s ridley, giving them the status of protected species with a permanent prohibition on harvest (Sánchez et al. 1989, SEPESCA 1990). Despite these measures, the marine turtle populations continued to diminish. A total ban on harvest for all species was declared by the Mexican Fishery authorities for the 1971-1972 period (Márquez 1977, 1996a; INP 1990, Márquez et al. 1992). In 1982, the Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano y Ecología (Secretariat of Urban Development and Ecology) was created (SEPESCA 1990). Among the duties of this Federal Agency were the protection and conservation of endangered species, including all the marine turtle species within the national jurisdiction. Due to population declines, the capture permits for the black sea turtles were not renewed in 1983. Capture permits of 200 animals per tribe were only given to the Seri, Pómaro and Huave Indian groups (Márquez 1996a). In 1972, a juridical exception gave a global catch quota to the Sociedades Cooperativas de Producción Pesquera (Cooperative Societies of Fishery Production). This quota gave the Cooperatives an exclusive right to catch marine turtles in national waters (Márquez 1977, 1996a; INP 1990; SEPESCA 1990; Márquez et al. 1992). This initiative is found in the Ley Federal para el Fomento de la Pesca (SEPESCA 1990). Because of the heavy exploitation and the slow recuperation of turtle populations, the closed season was prolonged to 1972, and in 1973 seasonal bans was declared. These bans were from May to August in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, and from June to September in the Pacific (Márquez et al. 1992, Márquez 1996a). In 1975, this ban was extended one month to September and October in the respective areas (Márquez et al. 1992, Márquez 1996a). In 1986, Mexico’s President signed legislation naming 17 sea turtle nesting refuges within Mexico on the Pacific, Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean coasts (Diario Oficial de la Federacion (DOF), 29 October 1986; INP 1990; SEPESCA 1990). These areas were called Reserve Zones for the conservation, re-population, development, and control of marine turtle rookeries. The presidential decree made Rancho Nuevo a natural reserve, and included Playa Escobilla in this category as well. In that same year, however, the Government maintained quotas for the Cooperatives. It was still illegal of the destroy nests, or to collect eggs. In 1987, to combat declines in marine turtle populations, the Fishery authorities permitted the capture of the olive ridley sea turtle only for the Cooperatives of Oaxaca, Michoacán and Guerrero (Anonymous 1988). Nine of these cooperatives were in the State of Oaxaca. Even with the quota system, quota overshoots persisted. From 1973 to the end of the 1970’s, public managers tried to maintain the total annual catch at 100,000 animals (INP 1990). However, turtle populations continued to decrease. Indications are that the Cooperatives over-shot their quota, and illegal catch by unauthorized fishermen increased as well (Table 2). Since the surveillance of the fishery was weak, the black market of turtle leather and eggs escalated (Márquez 1977). Legislation has sometimes been adapted to the cultural and subsistence importance of marine turtles to Coastal Indian communities. In 1988, the Mexican Government promulgated its environmental legislation, the Ley General de Equilibrio Ecológico y Protección al Ambiente (SEPESCA 1990). This law gives strict measures not only to protect the habitat and the species of marine turtles, but also to preserve biodiversity and natural habitat of the flora and fauna within the national territory (Article 45, II; Art. 79). Finally, on May 28, 1990, the Federal Government proclaimed the National Program for the Protection, Preservation and Research of Marine Turtles. It involved a total ban on harvest of turtles and eggs, and on the trade in sea turtle products (SEPESCA 1990; Márquez et al. 1992; Márquez 1996a, 1996b), including all the captures of olive ridley turtles. A job re-training and subsistence re-orientation plan was included in this program to help the Cooperatives search for other economically viable alternatives to turtles. This was to be done with the help of the Fishery Ministers in the affected regions In 1976, these groups from the Pacific coast received permission for a limited capture of black sea turtle (SEPESCA 1990). In 1977, the Fishery authorities introduced a franchise system during the closed seasons to avoid the illegal capture by the means of a legal and controlled capture (Márquez et al. 1989, 1992; SEPESCA 1990; Márquez 1996a). During the existence of this system, the capture increased to 150,000 (Márquez et al. 1989). It then diminished to 110,000 animals in the 3 IIFET 2000 Proceedings 16000 14000 12000 Tons 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 1989 1988 1987 1986 1985 1984 1983 1982 1981 1980 1979 1978 1977 1976 1975 1974 1973 1972 1971 1970 1969 1968 1967 1966 1965 1964 1963 1962 1961 1960 1959 1958 1957 1956 1955 0 Year Figure 1. Turtle Catch in Pacific Mexico, 1955-1989. has coastal zone inspectors charged with enforcement of environmental norms and laws, such as those that concern the illegal market of marine turtle products. (Márquez et al. 1992). This attempt at re-tooling the fishing industry appears to have had limited results. A quota of 23,000 animals was allocated from July 1989 to May 1990 (SEPESCA 1990; Márquez 1996a) despite the program. The offshore shrimp fishery is an important factor in sea turtle mortality. For this reason, and also because the United States threatened embargos of Mexican shrimp products, the National Fishery Institute began preliminary tests on Turtle Excluder Devices (TED’s) in national waters. Legislation subsequently emerged (NOM-002PESCA-1993, Federation Official Journal the 25th February 1993) obliging the utilisation of TED’s in Mexican shrimp trawlers of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea (Ramírez 1995). To reinforce this new plan, and to assure successful attempts at research, preservation and surveillance, several Federal institutions signed an agreement in May 1990 (SEPESCA, 1992). Even with the moratorium, illegal catch and egg harvests continued, and continue to the present day. In fact, illegal turtle eggs still supply markets in Mexico City, Guadalajara, Mazatlán, Oaxaca and Acapulco (Ramírez 1995). To encourage conservation, protection and research efforts, as a part of the Código de Ensenada, (Ensenada Code) the Federal Government (September 24, 1991) opened the Turtle Museum and the National Mexican Turtle Center, in Mazunte, Oaxaca in September of 1991. Illegal sea turtle catch, poaching of eggs, as well as commerce in sea turtle parts are now punishable by prison terms, beginning in December 1991 (SEMARNAP 1997). The Federal Government created the Inter-ministerial Commission for the Protection and Conservation of Marine Turtles. The academic sector became a necessary part of this effort. In April 1994 the National Committee for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles was established. This committee was to support research, protection, conservation, and sustainable development of sea turtle populations, and to promote economic alternatives to foster local and regional development of coastal communities that rely on sea turtles (Comité Nacional para la Protección y Conservación de las Tortugas Marinas, 1995). PROFEPA (Procuraduria Federal de Proteccion al Ambiente) is an environmental enforcement agency created in 1992, dedicated to enforcing environmental legislation and responding to popular complaints related to ecological damage. It works in co-ordination with governmental police and military agencies. PROFEPA 4 IIFET 2000 Proceedings period, and the ban was invoked in 1991, parts of the population had learned to depend on both the resource and certain techniques of exploitation. The ban then forced these activities underground, especially in poor areas. The Mexican Official Norm NOM-ECOL-059-1994 determines the species and subspecies of terrestrial and aquatic wildlife flora and fauna in danger of extinction, threatened, scarce and subject to special protection (Comision Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, (CONABIO). 1997). All marine turtle species in national coastal waters are considered endangered species and measures are proposed for its protection. In December 1994 the Secretariat of the Environment, Natural Resources, and Fisheries (SEMARNAP) was created to implement the environmental reform. In the Pacific Mexican waters legislation requiring the employment of the Turtle Excluder Devices in shrimp fishery operations came out in the Mexican Official Norm of Emergency NOM-EM001-PESC-1996 (SEMARNAP 1996). The areas subject to these laws is an important factor. For example, the State of Oaxaca, is in southeast Mexico. It is often caracterized as resource rich but with large populations of poor and underemployed persons, especially in rural areas. There are important native populations as well. The coast in Oaxaca is 340 kilometers, which has nesting sites for the olive ridley. Playa La Escobilla is one of the most important olive ridley nesting sites in the world. The area is not only important for this species, but also for others like the leatherback turtle. The coast of Oaxaca is home to 95% of sea turtles in Mexico (Vasconcelos, pers. comm. 1999). The size of Oaxaca’s coast makes it difficult to enforce anti-poaching laws. Therefore, a substantial illegal harvest probably continues in certain areas. Natural factors can also affect turtle populations. In October 1997, hurricane Paulina damaged almost all of the 806,000 nests registered that year (Vasconcelos Pérez, pers. comm.). Recently, the SEMARNAP announced a legal initiative concerning wild flora and fauna (Cantú 2000, personal communication). Cantú remarks that there are two articles having application to marine turtles in Mexican waters. Article 1 refers to the sustainable exploitation of species whose total life cycle depends on water, except for populations or species in danger. Article 7 (a provisional article), allows the Federal Government to amend decrees, bans and international commerce restrictions which are opposed to this new law; and to repeal them if necessary. This proposal has already been adopted without analysis by the Congressional Commission on Ecology. It’s implications are uncertain, and could even mean that the ban on turtle exploitation could be abolished. There has been a partial rebound of the olive ridley at Playa Escobilla since the beginning of the 1990’s (Márquez et al. 1996 in Godfrey, 1997). Discussions have arisen between some Cooperatives and the Mexican Government about the possibility of a season opening (Márquez 1996b). Fishermen argue that the population has increased, so their exploitation would cause little damage. Although there is some evidence of this, there is still uncertainty about the validity of the data used to make these arguments. Others argue that the existence of other natural and human induced factors must be considered besides the growth of the nesting sites in La Escobilla. For example, fishing fleets from Venezuela and Spain, operating off the Pacific coast of Guatemala, take large incidental catches of olive ridleys, as well as other turtles. Several aspects of the Penal Code concerning environmental crimes, which deal directly with marine turtles and their eggs, may be repealed as well. One proposed Article says that no sentence will be applicable in cases where a person identified as a fisher engages in egg collection for purposes of subsistence, or for satisfying basic needs of him or his family. As Cantú (2000, pers. comm.) remarks, there is no clear definition yet as to what “satisfying basic needs” actually means. Pritchard (1997) provides some reasons to continue with protection policies in Mexico. First, controlled turtle exploitation for local people is recommended in places where the turtle populations are stable. Yet it remains unclear what the best institutional setting should be for this exploitation, and how the appropriate levels of exploitation should be established. Pritchard also points out that slaughter of turtles for the leather market does very little for local people. However, this may or may not be true, depending upon the structure of the market, and the nature and enforceability of the bans on turtle parts. Although the international market of olive ridley leather is banned by both Mexico and its major trading partners, a modest black market in leather still exists. Policies having 2.1 Discussion of the Legislative History Mexico’s efforts to conserve the turtle resource did not lack legal frameworks. The legislative attempts at managing the resource follow steps that suggest continual effort to evolve the law to fit a number of realities, including subsistence issues. However, the conservation laws were significantly weakened by attempts to use the then abundant resource for regional developement, first through private enterprises, and then through state cooperatives. These attempts accentuated the dependence of local communities on the resource. When conservation objectives became important at the end of the industrial 5 IIFET 2000 Proceedings the 1940’s with 82% of the total catch. Yet, turtle eggs and turtles have been an important source of food for coastal groups and even to populations far from rookeries in Oaxaca (Hernández & Elizalde 1989). Turtle eggs were taken to Tehuantepec, Salina Cruz or Juchitán markets. Juchitán is also a distribution center to other localities, such as Veracruz, Puebla, Mexico City, Guadalajara, Monterrey, and Central America. a conservation objective based upon interdiction may not eliminate economic waste or the underground economy. Eco-tourism shows potential, because a sub-set of the tourist population is interested in observing natural events like the arribada phenomenon. Turtle camp site provisions were an effort to place local volunteer and federally funded observers on site, both as a deterrent to poaching, but also as a means of collecting scientific information on turtle populations. Different sectors are now involved in this work: education and research institutions, non-governmental organisations, state governments and fishermen groups. In 1990, the World Bank gave financial support to the campsite program, with the objective of making them (12 camps) financially self-sufficient within a 7-year period, mostly through tourist activity (Garduño 1999, pers. comm.; INE 1999). This objective of financial self-sufficiency has not been met. There are now approximately 27 camps under the supervision of the National Ecology Institute (INE) and the National Fishery Institute (INP), although this number may rapidly decrease due to cutbacks in funding. On the other hand, the region has experienced an increase in unofficial campsites. For example, INE (1999) estimates that more than 80 unofficial campsites are in place each year. These sites may be in place for a number of economic and social reasons, including poaching. Clearly, self-financing with the sole objective of conservation has not worked well, yet the campsite concept continues for complex social and economic reasons. 2.2 The Industrial Period Márquez et al. (1992) described the first phase of the industrial exploitation between 1948 and 1959 as a rudimentary industry. Some of these rustic establishments were in Yucatán and in Baja California. The catches were on the order of 500 to 600 tons by year (Figure 1), principally from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean coast (Márquez 1977, Márquez et al. 1992). The relative lack of regulation in the turtle fishery provoked intensive captures that drove the Kemp’s ridley population in the Gulf of Mexico nearly to extinction (Márquez et al. 1992). In the 1960’s, industrial exploitation in the Pacific began. From 1955 to 1963, the average capture was 810 tons. For the 1964-65 period, it went to 2050 tons. Marine turtle leather replaced crocodile hide, in response to a growth in international demand during the early 1960’s, especially for the leather of the olive ridley turtle and for the shell of the hawksbill sea turtle. In 1966, the Pacific fishery took 97% of the national catch (Secretaría de Industria y Comercio 1972). Hernández & Elizalde (1989) cite 1955 as the starting year of the commercial turtle fishery in Oaxaca. Márquez (1977) indicates that in Oaxaca almost all the turtle catch was olive ridley. 2. THE EVOLUTION OF THE INDUSTRY The laws governing turtle use were not made in a vacuum. Many of the rules seemed to be aimed at regional development and employment, likely at the behest of those who could exert political pressure. When these activities were assumed by the state cooperatives, it became increasingly clear that furthering the objective of employment and economic development in this way might fail. This realization, as well as pressures from abroad to conserve the resource, led first to an attempt by the government to re-sell some of the the infrastructure to the Cooperatives, and then to the bans. In this section, we deal with the evolution of the industry, and the parallels between that development and the evolution of the laws. We concentrate mainly on the turtle and the egg hunts. All the turtles officially captured, and many poached as well, were taken to the San Agustinillo slaughterhouse, in that fishing village near Puerto Angel. In the late 1960’s in San Agustinillo, there was little attention paid to the complete use of the turtles captured, because only the leather had a ready market. Markets for meat were poorly developed, and so waste was on the order of tons (Hernández et al. 1989). It is likely that this is due to the markets for the rights to exploit the resource. Concessions for extractive industries are often accorded by governments at prices that are below the actual economic value of the resource. The choice of only one or two bidders in such a process may also result in an inefficient use of the resource from two perspectives. The competitiveness of the sector is not assured, and those who are particularly good at lobbying government officials for concessions may not be as effective as managers of a living resource and a rural workforce. 2.1 The Pre-industrial Fishery Before the industrial period of exploitation, the olive ridley populations in the Mexican Pacific were certainly self-sustaining at relatively large stock levels (Carr 1982, Hernández et. al 1989). The Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea were the main zones of sea turtle catch in 6 IIFET 2000 Proceedings For this reason, the commodities that were produced may not have reflected all the commercial value. A part of the amenities of wild life may not trade in markets, and in these cases, economic value is only observable from consumer behaviour in the use of other goods or services, and not as a unit of biological diversity (Brown 1986, Gowdy 1992). The opportunity cost of harvesting wild life commercially and using only certain parts can be therefore very elevated. Figure 2 depicts this situation. There is certainly an economic benefit to a trade in turtle skins, for example, which is represented by the area OAB. If the marginal opportunity costs for each turtle are ZX, then the social benefit of allowing a commercial turtle harvest appearing on this diagram, is OAB-XYAB, which in this case would be negative. If the private user had to pay the opportunity cost in this case, then no capture would occur. Y Elizalde 1989). The increasing catches from the beginning of the 1960's, and especially from 1968, may be related to growing international demand for leather (Márquez, 1977). The catch numbers from 1966 to 1971 show two stages of exploitation. The first period (1966-68) was effort expansion and pressure on catch in which catch was likely superior to the growth of the population. The latter period is associated with a harvest decline (1969-71). The outcome was a total capture ban for the years 1971-72. Even during this ban, illegal catch continued (Hernández & Elizalde 1989). The Cooperative fishery activities reopened in 1973, supplied by illegal captures, and due to political pressure from the Cooperatives. Their argument was that it made little sense to ban an economic activity that could not be effectively controlled. Supply of turtles at social opportunity cost. Year 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971* 1972* 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 Supply of turtles for leather only. X B O A Derived demand Z T* Total Average Turtles captured Figure 2. Private versus social cost of harvesting turtles for the leather. Official data Turtles Tons 2737 104 84 368 3206 9053 344 53131 2019 41053 1560 0 0 0 0 53046 2015,74 25493 968,73 58575 2225,84 40407 1535,46 56706 2154,85 424569 16133,62 35381 1344,46 Unofficial data Turtles Tons 60000 2280 120000 4560 65000 2470 60000 22280 50000 1900 25000 950 30000 1140 90000 3420 60000 2280 70000 2660 55000 2090 75000 2850 760000 48880 63333 2406,66 Table 2. Sea Turtle Catch in Oaxaca. Source: Martínez (1978). *ban years. The reason why the industrial fishery developed may be that there were other economic benefits of a more intensive capture which might not be accounted for in this diagram1. Alternatively, the net social benefits in the diagram might be considered a form of externality on society. That is, the acute need for employment in the regions, coupled by political pressure from entrepreneurs involved in the leather trade, may have blinded decisionmakers to the larger social costs. The intent of the 1971-72 ban was the reorganisation of the fishery. This reorganization included a more integral exploitation of the resource, recuperation programs under the management of the Fishermen Cooperatives, quotasystems conferred to coastal States, and a major effort at surveillance (Márquez 1977, Hernández et al. 1989). The protection of nesting beaches by the Cooperatives themselves, one cornerstone of this reorganization, was in some cases a failure. The quotas were not respected, mainly because of the leather and egg black market (Márquez 1977). Hernández et al. (1989) and Guerrero et al. (1989) pointed out that in Oaxaca from 1966-1977, the illegal catch exceeded the official catch by an average of 44,2%, or 760,000 marine turtles. This uncontrolled harvesting of marine turtles helped to cause the collapse of both the re-organization effort and several sea turtle populations in the Mexican Pacific. The all-time maximum of 15,000 tons was taken in 1968. This was taken almost entirely by the north Pacific States. Oaxaca accounted for 2,7% (405 tones) of the total (Hernández and Elizalde 1989). After this year, because of declining turtle populations in northern waters, Oaxaca became the predominant marine turtle fishery, reaching its maximum capture in 1975 (Table 2) (Hernández and 1 For example, benefits might accrue by keeping workers in a labor force, rather than leaving them idle or at subsistence levels for long periods. Market power may have played a role in the distribution of the benefits that did exist within the fishery. The 7 IIFET 2000 Proceedings background history of this structure was related during interviews with the Fishery Director from the Municipality of Pochutla (Herrera, pers. comm., 2000). In the early 1960s, two Cooperatives from Puerto Angel were producing leather from the olive ridley. This product was taken to Mexico City by an entrepreneur who was the only known buyer from the Cooperatives and the independent fishermen. PIOSA, a private fishing firm, controlled the industry from 1973 to 1980 (Hernández and Elizalde, 1989). Herrera points out that the owner of the firm had worked as an accountant in this enterprise in the 1960s. Later in the 1960’s he bought PIOSA. One of the improvements, as Herrera and Romero (1980) mention, was a more complete use of the olive ridley turtles. continued to control operations (Hernández & Elizalde, 1989). During the 1989-1990 seasons, with the total and permanent closed season for turtle catch, the situation became difficult for the Cooperatives. San Agustinillo Cooperative fishermen provided information to the authors about the status of the turtle fishery from their perspective. This Cooperative was founded in 1975 with 80 members, and during the peak years, it had a membership of 250 persons. Presently, it has 35 members. According to some sources, some years before the total ban, the maximum permitted quota was so low that revenues were insufficient to cover costs. However, this forced the exit of many fishers from the legal fishery to the illegal fishery, driving the harvesting activities underground. Four Cooperatives continued fishing. The quota allocations of 20 000 turtles was surpassed by an estimated 12,000 turtles (Guerrero et al. 1989, Aridjis 1990), and 99.66% of captured turtles were females. The promise of viable economic alternatives or employment opportunities as expressed in the 1990 Federal Agreement did not materialize. Conditions of fishers have deteriorated since the closure (Herrera 1999, pers. comm.). In June 1980, the Federal Government acquired the three processing industries of Suárez; PIOSA in Puerto Angel (Oaxaca), IPOSA in Barra de Navidad (Jalisco), and Procesadora del Pacífico in Lázaro Cárdenas (Michoacán) (Romero 1980). The total transaction was 36 million pesos ($1,566,580 US)2. The reason for the buyout was again to reorganise the fishery by involving fishermen as direct members of the transformation and conservation industry (Romero 1980). Cooperatives would have a 45% share in the business, and their debt would be paid with product. PROPEMEX (Productos Pesqueros Mexicanos) was thus created (Hernández & Elizalde, 1989) as a government enterprise to continue with the turtle monopoly and, according to one of the objectives, to improve the welfare of fishermen. However, the catch continued it’s downward trend, and in 1986 the Federal Government sought to sell the slaughterhouse at San Agustinillo and the processing establishment of Puerto Angel for 150 million pesos ($228,238 US) to the Cooperatives (Hernández & Elizalde, 1989). This deal included a fishermen compromise of paying the debt with product (67% of each turtle price), obliging them to sell to PROPEMEX. Only five Cooperatives (Mazunte, San Martín, Santa María, Puerto Escondido, and Pastoría) accepted the agreement, while the other four opted out. The turtle unit price was of 12,000 pesos ($8,20 US) for those Cooperatives who accepted the deal and 17,800 pesos ($12,16 US) for the others, in 1987. Even the Cooperatives who stayed out of the arrangement were obliged to sell their catch to PROPEMEX, mainly through extra-legal pressure. During the 1989-1990 season, PROPEMEX bought each turtle at 35,000 pesos ($12-14 US) for both groups of Cooperatives. There is some evidence that during this period, the fishers themselves did not experience many improvements in their commercial conditions. This may be because monopsony power was exercised both by private and state monopolies. In addition, corrupted government officials Throughout the existence of the industry, the wealth distribution among the stakeholders seemed skewed toward the transformation and distribution sector. Some socio-economic data from the 1989-1990 periods shows important differences in prices paid between Cooperative laborers, intermediaries, and illegitimate fishermen (Hernández & Elizalde, 1989). Hide buyers generally hired poacher/fishermen, who either were paid a salary or were paid by each turtle caught. The price for poached turtles was the highest to fishers at the time (Elizalde 1989). They received 350,000 pesos ($130 US) a day per person. Buyers also paid 40,000 pesos ($15 US) per turtle leather. The total daily capture for a crew of four was from 60 to 100 turtles for betwen 2,400,00 to 4,000,000 pesos ($900 to $1,500 US). On the other hand, Cooperative fishermen made 50,000 pesos ($18,7 US) for a capture day per person, only 14% of that obtained by poachers. Government administratively set the Cooperative price lower than that of the black market, for the reasons that were explained previously. Hernández & Elizalde (1989) remark that during these times, fishery restrictions permitted only 5 days of capture to Cooperatives, concluding that 250,000 pesos ($93,8 US) a month was the best a legal fisherman could do. In the national market, finished leather from one turtle was sold at more than 500,000 pesos ($188 US). The hide was usually tanned in one of the northern States of Mexico. The principal importers of leather were Spain, Japan, and the United States (Mack et al. 1981). A Federal State company, RETESA, distributed the product 2 All US dollar values are given in the exchange rate of the correspondent year. 8 IIFET 2000 Proceedings areas. Interviews with researchers as well as illegal resource users were conducted between the 96° 44’ W and 15° 47’ N between Puerto Angel and Puerto Escondido in the State of Oaxaca, during the summer of 2000. Conversations with members of the village of Escobilla were carried out to obtain information about the black market for the eggs of the olive ridley. These interviews also explored socio-economic conditions, and obtained perceptions of villagers as to the subsistence use of turtles during the ban. The information obtained, though not statistically representative, reveals interesting information about this area. It is important to note that the community in question does not exhibit large socioeconomic differences. The village of Escobilla has a population of approximately 478 habitants from which 235 are women and 243 men, within 93 families with an average of 5 persons per household. The schooling level of the population is low; 68% of the villagers have a primary education level (50,2%) or no school instruction (17.8%). in the United States. After the ban, Aridjis (1990) and a PROFEPA inspector in Puerto Escondido, Oaxaca, identified the city of Cacalotepec as a center of illegal traffic of the olive ridley (1999, pers. comm.). Presently, poachers are paid 50 pesos ($5.3 US) per turtle leather. An average of 60 olive ridley turtles brings 3,000 pesos ($320 US) for a working day. This suggests that the black market for turtle leather is less lucerative, compared to the past, but that it has not disappeared because of the ban. 2.3 Egg Harvesting for the Black Market Interviews with PROFEPA's inspector in 1999 reveal that the black market for turtle eggs is now a profitable and complex business. However, funding, human resources, and coordination are common difficulties encountered in the surveillance and enforcement of environmental legislation. At present, the coastal zone of Oaxaca has only 6 inspectors. They are responsible not only for fishery activities, but also look after forestry, wildlife, terrestrial and maritime federal zones, as well as following up on issues related to environmental impact assessment. Administrative bureaucracy is another issue that impedes the performance of PROFEPA. According to villagers, turtle egg commerce has been an important source of income. Nevertheless, the larger economic benefit is said to stay with the acaparadores. Egg poaching can be a lucrative business, with gains comparable with those from the traffic in drugs (Inspector of PROFEPA 1999, pers. comm.). In 1988, some 3 million olive ridley turtle eggs were harvested from Escobilla and Morro Ayuta rookeries. Each egg had a value of 50 pesos ($0.021 US) to the poachers, so the gross revenue to the egg poachers was 150 million pesos ($65,430 US) (Aridjis 1990). The price of turtle eggs in a Mexico City market was at the time 1,500 pesos ($0.65 US) each. Based upon this information the mark-up was close to 4500 million pesos ($1,962,922.6 US). These figures come from a case where a Marine officer used his office to confiscate turtle eggs, and then sold them himself on the black market (Aridjis 1990). On the other hand, the level of organization of poachers may exceed that of law enforcement. Distribution channels of black market turtle eggs covers the principal nesting beaches, local communities and routes, sometimes operating in co-operation with official agents and public bus drivers. When army check points are established, drivers communicate this information by radio contacts. The presence of corruption at different levels of government, the lack of coordination between enforcement agencies, and indifference to the problem (or even complicity) by some Federal Agencies contributes to enforcement problems. Corroborated interviews suggest that Fishery Inspectors and the Marines did not make inspections during arribazones to permit the collection of olive ridley eggs, in exchange for payoffs, during the 1989-1990 seasons (Aridjis 1990). Because PROFEPA attempts to intervene on the black market for turtle eggs, agents of the PGR attempt to pressure PROFEPA agents to abort their investigations. Enforcement data reveals that PROFEPA has been increasingly active during the 1995 to 1998 periods. In July 1999, PROFEPA, in coordination with the Mexican army confiscated approximately 180,000 olive ridley eggs from Escobilla beach poachers. It is estimated that 10 million turtle eggs a year supply the Mexican black market (Aridjis 1990). However, an important part of these margins, as in the case of drug traffiking, make up for the costs of risk bearing, both from the standpoint of price fluctuations and also from the standpoint of enforcement. During the peak season for turtle eggs, from July to December and especially during an arribazón, the price is extremely low, fluctuating between 10 to 30 pesos ($1,16 US- $3,22 US) for 100 eggs (one nest). As the eggs become scarce, from January to May, the prices rise to the 60-80 peso range ($6,4 US-$8,6 US) per 100 eggs. Egg buyers, being few, tend to establish the egg price. Egg collecting is usually done at peak season when eggs are abundant, and poachers are usually paid after the sale of the merchandise by the acaparador , thus shifting the risk to the collectors. 2.2.1 Subsistence and Black Markets in Escobilla The problem of egg poaching is considerably complicated by the fact that it is an economic activity of last resort, which provides both cash and food to people in rural Within the population of Escobilla, each family or group of persons coordinate themselves individually to harvest 9 IIFET 2000 Proceedings and sell the eggs. Each band or individual takes their own risks. According to some inhabitants of La Escobilla, it is usual for youths to be involved in egg poaching just before the school year (in September) in order to pay for school supplies. In these communities, the lure of high pay attracts not only collectors but also buyers. Since the market is underground, it is difficult for sellers to develop coalitions to negotiate better prices for the product. of the resource. To the contrary, institutional arrangements contributed mainly to management of the sea turtle resource as a centralized regulatory activity. As the olive ridley fishery developed in the Mexican Pacific, protection and conservation measures were mainly concentrated on the establishment of global quotas, enterprise allocations to Fisheries Cooperatives, closed seasons, as well as surveillance and control mechanisms. A look at the applicable law, however, suggests that little attention was paid to the social and cultural institutions already in place, and to the industrial organisation in the marine turtle fishery. Policies in force were not subjected to scrutiny and revision. As Townsend and Wilson (1987) point out: “the fundamental issue in the management of resources is the nature of the economic institutions.” On August 20th 1999, the Annual Reunion of Inspection and Surveillance Coordination of the Marine Turtle Program during the season 1999-2000 took place at the Mexican Turtle Center (Mazunte). The meeting concerned the problems in enforcing conservation programs, the activities to date, the future agreements to reinforce surveillance, and the use of alternative mechanisms (opening of a quota market, eco-tourism) to counteract illegal trade of sea turtle products. PROFEPA’s delegate in Oaxaca points out that the actual legislation does not sufficiently discriminate between a subsistence resource user and an acaparador. Perhaps more disturbing is that from the persons captured for egg poaching, a large number are women and children. Throughout much of the industrial exploitation of the sea turtles in Mexico, the understanding of the population dynamics was limited. The ecology of turtle populations, the influence of harvesting, and the response of populations to the fishing activities and regulations were also not very well recorded. Libecap (1987) distinguishes these limitations as constraints on fishers (and on legislators) which limit their ability to anticipate the possible effects of their actions. These are different from agreements or imposed rules. From 1929 to 1990, at least nine closed seasons, and several other measures were applied, which redistributed catch and income for those fishers who remained in the fishery. 3. DISCUSSION 3.1 Lessons From the Mexican Experience The turtle fishery in Mexico went from being fairly localized and limited to a full-blown industrial fishery over a relatively short period. This development was assisted by a several historical conditions. First, the legislative history reveals divided objectives of regional development and conservation, as perhaps it should have. At the same time, developments in world markets for leather pushed development of the fishery along as well. Although it is difficult to say with certainty, the passage of the industry from private to government hands was probably because the asset value of the resource declined, motivating private interests to sell to the Government. The government was then saddled with a public project that, from a financial standpoint, was destined to fail because the resource was failing. Pressure from abroad and at home caused the Federal government to make conservation a priority, and in 1990, the ban was put in place. From a strictly dynamic control standpoint, opening and shutting exploitation in this manner makes some sense3. However, the regulatory structure proposed did not sufficiently take into account the challenges confronted by the both families and fishers in changing their economic activities to better fit with a conservation effort. Few incentives, other than purely regulatory, appear to have been created to promote the conservation The ability of fishermen to act as lobbyists depends upon their opportunity to act as a homogeneous group, as well as their numbers. They were numerous, but this circumstance may have been more an obstacle because of transaction costs. In this case, where sellers were more atomistic, small numbers of buyers may have been able to exert market power. Even the Cooperatives had to adapt to industrial conditions where market power was held by the government. The 1987 exclusive permits for capturing marine turtles given to the Cooperatives of Michoacan, Guerrero and Oaxaca (9 of them in this last State) was not simply to favor rent seekers who happened to successfully lobby the government. It was also to assure that the Cooperatives would be able to repay their government loans and to guarantee the delivery of turtles to a Federally owned processing industry. The way in which turtles have been managed in Mexico led to an industry structure less based upon sustainable management, responding instead to employment needs through centralized management. The Mexican Federal Government appears then to have been centralized in its approach to resource management. This condition may have induced political pressure by many claimants; each one of them demanding benefits 3 This might be thought of as the institutional equivalent of an on/off control. 10 IIFET 2000 Proceedings programs seemed ineffective. In addition, the moratorium was partially lifted for some and not for others, which may have been seen by some as unjust. Therefore, as other fisheries where moratoriums were imposed with little back-up policy, the result has been the perpetuation of the common pool condition, and the development of an underground market. Even with the ban now in place, a number of social and economic issues remain that appear to be related to policies from the past. Legislative history and industry practice are two reasons why poaching is persistant today. Also, conservation laws do not explicitly recognize the existence of government corruption, and no measures are outlined for curbing abuses. Many examples seem to suggest directly unproductive profit seeking. Low salaries of public officials and the lack of incentives for good behavior exacerbate this problem. from the resource. Fishing permit owners (Cooperatives and independant fishers as well as poachers) increased during the peak harvesting years. Central authorities, especially those having personal stakes in resource exploitation, might be expected to encourage common pool conditions for a number of reasons. The Federal government heavily invested in regional projects to provide employment to marginalized work forces. During these periods, protection and conservation were less important than development objectives. However, catch was allowed to expand, and capture technologies and markets consequently developed and persisted. It is this persistance and resistance to change that eventually stressed the turtle resource. In this case, the effort eventually was concentrated at over 90% on female reproductive turtles. Signs of population decline appeared, and by 1980, commercial profitability was in decline. In this year, the original concession holder sold three slaughterhouses to the Federal Government. Non-enforceability might also have to do with the social attitudes about the justice of the conservation laws. If many people believe that the turtle populations are in less danger now, then poaching might be an expression of civil disobedience aimed at an unjust law. Mexican coastal populations might take the attitude that their activity is not the primary reason for declining turtle populations. Rather, it is offshore fishing pressure and the incidental catch of turtles. Why should they stop doing something they have always done, adds to the local economy, feeds people, and provides employment, when turtles are being slaughtered by the thousands as incidental catch, often by illegal foreign fishermen? The economic history of this story has some significance. Centralized governments sometimes search for centralized solutions to their problems. Granting concessions for resource exploitation to a limited number of entrepreneurs is one way of rapidly developing a resource using the managerial skills of the private sector. However, there is no guarantee that the entrepreneur who is favored with the concession will act in a resourceconserving manner. Also, monopoly behavior is thought to be resource conserving in some cases. Why then, did we see a decline in the turtle resource in Mexico? It may be that the entrepreneur in question treated the turtle resource as a damaged capital asset. If the entrepreneur used his own resources to obtain the concession, and if he was not liable for the depreciation of the asset, he might exploit it until its residual earnings were equal to earnings he could make in an alternative venture. At this point, he would then attempt to sell. The terms of the concession or contract between the Federal Government and the concession holder may have motivated the overexploitation. Governments are sometimes faulted for selling public assets at very low prices, sometimes for objectives of regional employment. They may even buy the residual asset back for other uses, sometimes at unreasonably high prices, again to stabilize regional employment. This may have been the case for the turtle resource in Mexico. 3.2 Conclusion: Where to Go From Here? If our historical interpretation is correct, it may be important for the Mexican government to institute regulatory and conservation policy which is consistent with the new realities of sustainable resource management. This may require models of governance that encourages a more active participation by resource users in local communities. It would also be useful to have policies that encourage the generation of information on the removals of turtles and eggs, and that more carefully tracks impacts on the communities by gathering sociological and economic data. Also, whatever policy proposed should also create incentives for sustainable use of the resource. By the time that the Federal Government decided that the species group was endangered, a culture of hunting and egg collection was strongly in place. An adjustment period, and policies of adjustment in order to allow those who depended upon the resource to develop other sources of revenue, did not appear to be well organized. The moratorium on turtle fishing got little support from the fishing community mainly because they were not consulted, and the re-training and re-orientation of labor One policy already discussed by PROFEPA is legal subsistence quotas for eggs and turtle harvests; a sort of controlled exploitation allowance. It is obvious that the black market has not been eradicated. There is even evidence of a flourishing underground economy of turtle products, most of the time favored by corruption. RoseAckerman (1998), in her analyses of anti-corruption reforms, has proposed legalization of unlawful activities 11 IIFET 2000 Proceedings The promotion of tourism in areas of exotic bio-diversity probably should be more seriously attacked. In addition, the active implication of members of the local community in a tourist industry could go far in encouraging the sustainable use of the resource. The more destructive aspects of the Mexican experience have to do with locals simply trying to make a living. If it is not too costly to retrain locals to make a living from the turtle resource in less destructive ways, this might promte a more sustainable use of the resource. Rookeries usually occur in regions with magnificent geographic attributes. This could be used as an opportunity to develop eco-tourism destinations, employing local people as well. This may also have the effect of increasing the likelihood of enforcing conservation measures. There are drawbacks to this proposal. Coastal development aimed at attracting tourists often requires important investments in infrastructure. Coastal development aimed at attracting the eco-tourist may be less costly, but then eco-tourists do not usually have a demographic profile synonymous with big spending, although this may be changing. These are other, and possibly happier, problems that await resource managers in Mexico. However, these problems probably cannot be tackled effectively unless the status quo is recognized as unacceptable, and unless the present situation is understood as the cumulative result of Mexico’s own conflicting policies in the past. as a way to diminish corruption. Making the harvest of some turtle eggs and hide legal might diminish enforcement costs, and diminish conflicts between stakeholders. Another possible reform might be management decentralization to the regions. Promoting decentralization of resource management to the States, with appropriate federal funding, could reduce some costs of bureaucracy and administrative procedures, and would give the opportunity to each particular region to develop its own management strategies. This might also promote better communication among stakeholders, by lowering the costs of being heard. Related to the issue of information costs, regional jurisdictions that conform more or less to different nesting beaches might give regional resource users more say in how regional resources are being used. This should help enforcement efforts by encouraging some policing by the resource users themselves. It would also reduce the probability of decisions being made in Mexico City without due consideration to regional realities. Such a policy might also reduce the number of federal agencies in management and enforcement actions. Related to this proposal might be a recomnendation of promoting increased community participation in management decisions. Sea turtle international agreements (like the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles) have so far given limited attention to the issue of participatory management by local communities and the need to incorporate sea turtle conservation in socioeconomic development. However, in many developing countries of the world, user participation is playing an increasingly important role in establishing the rules by which resources will be used. This is because protection and enforcement activities by central authorities are too costly without the implication of the resource users themselves. Labor problems may be partially solved by establishing appropriate subsistance policies for local inhabitants. Those living close to rookeries could be able to pursue their traditional activities as part of this participation. Communities adjoining important ecosystems could play an important role in bio-diversity protection in conservation zones, if their function is legally recognized. This issue of legal recognition of local management bodies is recognized by some institutional analysts to be an important aspect of successful community based management policies. Conservation of cultural resources may also be critical in promoting and achieving the conservation of biological resources (Nietschmann 1983). Another approach could be to establish a legally constituted association including both communities and the government, with a mandate to manage specific zones. Acknowledgements The authors thank the staff at Centro Mexicano de la Tortuga, representatives at Procuraduria Federal de Proteccion al Ambiente, as well as contacts at Productos Pesqueros Mexicanos, Instituto Nacional de la Pesca, Secretaria de Marina, Secretaria de la Defensa Nacional, Secretaria del Medio Ambiente Recursos Naturales y Pesca and Secretaria de Desarrollo Urbano et Ecologica. The authors benefitted from travel grants from Université du Québec à Rimouski. Comments can be directed to James_wilson@uqar.uquebec.ca. The authors are responsible for remaining errors. 4. References Anonymous. Mexico’s Sea Turtle Program. Marine Fisheries Review, Vol. 50, No. 3, 70-72, 1988. Aridjis, H. La tortuga marina, a la extinción (2a. y 3a. parte). Diario La Jornada, 24 y 25 de enero de 1990, 1990. Bjorndal, K.A., ed. Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles, Proceedings of the World Conference on Sea Turtle Conservation, Washington, D.C. 2630 nov. 1979, Smithsonian Institution Press, 602 p, 1981 . 12 IIFET 2000 Proceedings Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF). « ACUERDO por el que se establece veda para todas las especies y subespecies de tortuga marina en aguas de jurisdicción nacional de los litorales del Océano Pacífico, Golfo de México y Mar Caribe », 28 de mayo de 1990. Becker, G. S., Crime and Punishment: an Economic Approach, Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169-212, 1968. Briseño-Dueñas R., R. Márquez-Millán, D. Ríos-Olmeda, B. Bowen and F.A. Abreu-Grobios. Population structure of olive ridley rookeries in the eastern pacific: what does the mtDNA offer management practices? Poster presented at: Nineteenth Annual Simposium on Sea Turle Conservation and Biology, 1-5 March 1999, South Padre Island, Tex.USA. Elizalde, C., Programa de Educación Ambiental: Apoyo a la Conservación de Tortugas Marinas in Hernández et al., 51-63, 1989. Godfrey, M.H., Further Scrutiny of Mexican Ridley Population Trends. Marine Turtle Newsletter No. 76, 17-18, 1997. Gowdy, J.M., Economic and Biological Aspects of Genetic Diversity, Society and Natural Resources, Vol. 6, pp. 1-16, 1992. Brown, G. Jr., Preserving endangered species and other biological resources, The Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 56, pp. 89-97, 1986. Carr, A.F., Sea Turtles and National Parks in the Caribbean, in McNeely & Miller (eds.), 601-606, 1982. Guerrero, L.; Ruiz, G.; Hernández, E.; Elizalde, C.; Silva, J.; Hernández, G. and Macho, G., Rastro San Agustinillo, Proyecto de Tortugas Marinas en las Costas de Oaxaca, especial atención a Lepidochelys olivacea , in Hernández et al., pp. 41-50, 1989. Charles, A. T., Fishery Enforcement: Economic Analyses and Operational Models. Halifax: Oceans Institute of Canada, 1993. Hernández, E.; Ruiz, G.; Elizalde, C.; Guerrero, L., Programa de Investigación y Conservación de Tortugas Marinas en las Costas de Oaxaca, México; especial atención a la Tortuga Golfina (Lepidochelys olivacea); Reporte Técnico Temporada, 87 p, 1989. Charles, A.T., R. L. Mazany, and Melvin Cross. The Economics of Illegal Fishing: A Behavioral Model, Marine Resource Economics, 14, 95110, 1999. Comité Nacional para la Protección y Conservación de las Tortugas Marinas, Informe Anual del Comité Nacional para la Protección y Conservación de Tortugas Marinas (abril de 1994-abril de 1995). 37 p, 1995. Hernández, E.; Elizalde, C., Algunos Aspectos de la Problemática en torno al Recurso Tortuguero en el Estado de Oaxaca, in Hernández et al., pp. 6473, 1989. CONABIO, Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-ECOL-0591994, que determina las especies y subespecies de flora y fauna silvestres terrestres y acuáticas en peligro de extinción, amenazadas, raras y las sujetas a protección especial y que establece especificaciones para su protección, 1997. URL:http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/n om-059.htm Hurricane Paulina destroyed 40 million sea turtle eggs in the Oaxacan Beach of Mazunte. Marine Turtle Newsletter, No. 78, pp. 26. Instituto Nacional de Ecología (INE), Programa de Protección y Conservación de Tortugas Marinas, 1999.URL:http://www.ine.gob.mx/upsec/progra mas/prog_cvs/tortmar.htm Universidad de Guadalajara. Constitución Política Mexicana,URL:http://webdemexico.com.mx/poli tica/constitucion/index.html Instituto Nacional de la Pesca (INP), XXV Años de Investigación, Conservación y Protección de la Tortuga Marina, Secretaría de Pesca, 48 p, 1990. Lagueux, C.J., Economic Analysis of Sea Turtle Eggs in a Coastal Community on the Pacific Coast of Honduras; in Robinson & Redford (eds.), pp. 136-144, 1991. Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF). «Decreto por el que se determinan como zonas de reserva y sitios de refugio para la protección, conservación, repoblación, desarrollo y control, de las diversas especies de tortuga marina, los lugares en que anida y desova dicha especie », 29 de octubre de 1986. Ley General del Equilibrio Ecológico y Protección al Ambiente(LGEEPA),URL:http://www.cespedes. org.mx/sistemas/contexto/lgeepa/ 13 IIFET 2000 Proceedings Nietschmann, B., Indigenous Island Peoples, Living Resources and Protected Areas, in McNeely, J.A. and K.E. Miller (eds.), National Parks, Conservation, and Development: The Role of Protected Areas in Sustaining Society, Proceedings of the World Congress on National Parks, Bali, Indonesia, 11-22 October 1982. Smithsonian Institution Press, 825 p, 1983. Libecap, G., Contracting for property rights, Cambridge University Press, 132 p, 1987. Mack, D., N. Duplaix and S. Wells, Sea Turtles, Animals of Divisible Parts: International Trade in Sea Turtle Products, in Bjorndal, 545-563, 1981. Márquez, R. 1977. Estado Actual de las Pesquerías de Tortugas Marinas en México. Memorias 5o Congreso Nacional de Oceanografía, Guaymas, Sonora, México 1974, pp. 369-391. Pandav, Bivash and Choudhury, B.C. , An Update on the Mortality of the Olive Ridley Sea Turtles in Orissa, India. Marine Turtle Newsletter, No. 83, 10-12, 1999. Márquez, R. Sea Turtles of the World. FAO Fisheries Synopsis, No. 125, Vol. 11, 74 p, 1990. Márquez, R. Las Tortugas Marinas y Nuestro Tiempo. Colección La Ciencia 144, Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, D.F., 197 p, 1996a. Peñaflores-Salazar, C. and J. Nataren, Resultados de las Acciones Proteccionistas para las Tortugas Marinas en el Estado de Oaxaca. Los Recursos Pesqueros del País, 339-350, 1988. Márquez, R. Olive Ridley Turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) show signs of recovery at La Escobilla, Oaxaca. Marine Turtle Newsletter, 73, 5-7, 1996b. Pritchard, P.C.H. A New Interpretation of Mexican Ridley Population Trends. Marine Turtle Newsletter, No. 76, 14-17, 1997. Márquez, R., A. Villanueva, C. Peñaflores, D. Ríos, Situación Actual y Recomendaciones para el Manejo de las Tortugas Marinas de la Costa Occidental Mexicana, en especial la Tortuga Golfina Lepidochelys olivacea, in SEPESCA, 715, 1989. PROFEPA, Escobilla olive ridley turtle eggs confiscation. Videocassette VHS, 18 min., sound, color, 1999. Ramírez, J. 1995. Las Tortugas Marinas en México. Biodiversitas, Año 1, núm.1, URL:http://www.conabio.gob.mx/biodiversitas/t ortugas.htm Márquez, R., Vasconcelos, J., López, L., Bolaños, E. Diagnóstico de la situación de las acciones de conservación, protección y repoblación de las tortugas marinas: I Reunión Regional de Trabajo sobre la Problemática Camarón-Tortuga Marina. Secretaría de Pesca. Instituto Nacional de la Pesca, 1992. Robinson, J.G. and K.H. Redford (eds.), Neotropical Wildlife Use and Conservation, The University of Chicago Press, 520 p, 1991. Romero, N., La Tortuga Marina, Protección o Ecocidio. Técnica Pesquera,Vol. 13, No. 153, 22-27, 1980. Márquez, R., Peñaflores, C., et Vasconcelos, J., Monitoring the Abundance of Olive Ridley Sea Turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea), in La Escobilla, Oaxaca, Mexico. Developing and sustaining world fisheries resources. The State of Science and Management, 620-624, 1997. Rose-Ackerman, S., Une stratégie de réforme anticorruption. Mondes en Développement, Tome 26, No. 102, 41-54, 1998. Sánchez, J., J. Vasconcelos, and J. Díaz, Campamentos para Investigación, Protección y Fomento de Tortugas Marinas, in SEPESCA, pp. 17-26, 1989. Martínez, G..A., Informe de Avances sobre la Pesquería e Incubación del Huevo de Tortuga Marina en el Estado de Oaxaca, 1978. Secretaría de Industria y Comercio, Disposiciones sobre la captura, aprovechamiento y comercializacion de la tortuga marina. Dirección General de Pesca e Industrias Conexas, 1968. McCay, B.J. and J.M. Acheson, (ed.), The Question of the Commons: The Culture and Ecology of Communal Resources. The University of Arizona Press, 452 p, 1987. Secretaría de Industria y Comercio, Monografía de la Tortuga. Subsecretaría de Pesca, 1972. 14 IIFET 2000 Proceedings Secretaría de Pesca (SEPESCA), Compilación TORTUGAS Golfina, Laúd, Prieta, Lora, Blanca, Cahuama y Carey, 65 p, 1989. Secretaría de Pesca (SEPESCA), Programa Nacional de Investigación, Conservación y Fomento de Tortugas Marinas, 15 p. , 1990. Secretaría de Pesca (SEPESCA), Protección a la Tortuga Marina. 75 p., 1992. SEMARNAP (Secretaría del Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca), 1996. URL:http://www.semarnap.gob.mx/Noticias/dof/ diario.htm SEMARNAP (Secretaría del Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca), Acciones de México para la Conservación de Tortugas Marinas, 1997. URL:http://www.semarnap.gob.mx/indices/vario s/tortugas.htm Skonhoft, A. and J.T. Solstad, The Political Economy of Wildlife Exploitation. Land Economics, Vol. 74, No. 1, 16-31, 1998. Stigler, G.J. Theories of Economic Regulation. Bell Journal of Economics, 2(1), 3-21, 1971 Townsend, R. and J.A. Wilson, An Economic View of the Tragedy of the Commons in McCay & Acheson, 311-326, 1987. Vasconcelos, J. and E. Albavera, National Mexican Turtle Center. Marine Turtle Newsletter, No. 69, 14-16, 1995. Woody, J.B., Mexico Establishes Sea Turtle Refuges. Marine Turtle Newsletter, No. 39, p.9, 1986. 15