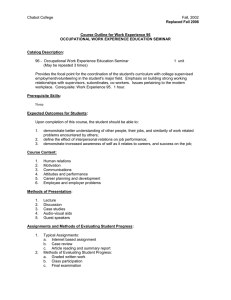

UCL MEDICAL SCHOOL RESEARCH DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY CARE & POPULATION HEALTH

UCL MEDICAL SCHOOL

RESEARCH DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY CARE & POPULATION HEALTH

Community Based Teaching

Year 5

Core General Practice

Course Materials

2015/16

Core General Practice

Course Materials

Contents

Introduction to the attachment

Seminar 1

The organisation of General Practice and Primary Care

Seminar 2

The content of general practice

Seminar 3

Common problems in general practice: an afternoon surgery

Seminar 4

Chronic care in general practice

Seminar 5

Introduction to Occupational Medicine

Sample Timetable

Assessment forms

(copies for information)

- Essay marking schedule

- Student checklist

Miscellaneous

21

27

28

29

23

26

16

20

3

4

2

Introduction to the fifth year Core GP Attachment

This booklet provides an outline of each of the Core GP Seminars provided during this attachment. Reading materials are also provided for some of the seminars. The booklet is provided for use in combination with the Year 5 Study Guide. Please refer to the Study Guide for details of the GP Course aims, objectives, core curriculum, assessment details etc.

Seminar teaching in general practice

In order to give you a maximum amount of exposure to the day-to-day work of general practice we have kept the seminar programme to a minimum. The short programmes of seminars in week one are seen as an important part of the course and will help you to get the most out of your GP attachment.

Seminar teaching in week one will include case studies and small group work. The following topics are included in the programme:

The organisation of primary care

What goes on in general practice?

Common problems in General Practice

Chronic care in General Practice

Occupational medicine

No formal preparation is necessary though discussion benefits from your raising examples of patients you have seen in consultations in practice.

The seminars in the department are an integral part of the course.

Full attendance at these is required.

Please arrive promptly as the seminars will start at the allocated time.

All absences will be reported to the medical school. If you have a genuine reason for being unable to attend a seminar, please let Mrs Sandra Gerrard, the course administrator, know

(tel: 020 7830 2599 or email s.gerrard@ucl.ac.uk

).

On Friday of weeks one and four you will be attending Clinical and Professional Practice

(formerly VM) teaching at the medical school.

3

Core GP Seminar 1

The Organisation of General Practice and Primary Care

Aims:

Objectives:

1.

To introduce the programme for the four week Core GP attachment within the Child and Family Health Block

2.

To explore the meaning of primary health care and how primary health care services are organised in the UK

By the end of the seminar you should be:

1. clear about the aims and requirements of the teaching programme for the 4 week Core GP attachment

2. able to provide a broad definition of primary health care.

3. able to describe the current organisation of primary care in the UK

References : Simon C, Everitt H, Van Dorp F. Oxford Handbook of General

Practice. Oxford University Press 2009

Cartwright S & Godlee C. Churchill’s Pocketbook of General Practice.

Churchill Livingstone 2008

Stephenson A. A Textbook of General Practice. Hodder Arnold, 2011

Booton P, Cooper C, Easton G, Harper M. General Practice at a

Glance Wiley-Blackwell 2012

GP Websites

There are numerous websites related to general practice and quality is variable often with commercial interests affecting content. We do recommend that all students browse the

Internet to see the sort of information, which is available both to patients and to health professionals. In particular the following may be useful

NHS Choices on:

Department of Health website on:

Doctors.net.uk on:

Royal College of General Practitioners http://www.nhs.uk/Pages/HomePage.aspx

http://www.dh.gov.uk/ http://www.doctors.net.uk/ http://www.rcgp.org.uk/

National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence

Prodigy: NHS Clinical Knowledge Summaries (Prodigy)

GP Notebook http://www.nice.org.uk/ http://cks.library.nhs.uk/ http://www.gpnotebook.co.uk/

4

Notes for Seminar 1

1. A Background to General Practice

In UK society general practice occupies a central position in terms of people’s use of formal health care provision. Most people when they refer to “their doctor” are talking about their

General Practitioner.

Today general practice forms the largest sector of the National Health Service and 90% of contacts with the NHS take place in this setting. GPs are on the front line of healthcare dealing with the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of health problems and providing continuity and coordination when patient care involves other aspects of the health care system.

The title “General Practitioner” was first used in the early 19th century to describe doctors available to be directly approached by patients regarding medical or surgical problems of any sort. Until the 1970s in the UK any doctor could theoretically take up work as a GP. Since that time however regulations have been introduced so that all GPs must be “vocationally trained” This means they must have completed a minimum amount of four years in a variety of hospital posts and a year as a GP Registrar before gaining accreditation. Primary Care

(sometimes referred to as Primary Health Care) is a more general term which has come into use in recent years to include general practice but also cover other aspects of health care delivered by a variety of health professionals as discussed below. In broad terms we can think of primary care services as those services, usually based in the community, to which people have direct access. This is in contrast to secondary care, which describes services, usually more specialised and hospital based, which can only be accessed following referral from a primary care professional. In other countries, general practice is sometimes referred to as “Family Practice” or “Family Medicine”, reflecting the unique role of the GP in providing universal medical care for whole family rather than just individuals with a particular type of problems or of particular age or gender.

GPs must have a range of medical knowledge and skills and be capable of bringing many different approaches to bear on a problem. The GP also provides continuity of care for the patient - both through her or his own knowledge of the patient and through access to the patient’s life-long NHS records. The average length of contact between one person and their

GP is eleven years. As well as dealing with existing illness, disease and disability GPs are very much involved in health promotion and disease prevention

GPs hold a “contract”, currently with a local Primary Care Trust and as such they are not direct employees of the NHS in the way that hospital doctors are. This “independent contractor” status allows a considerable degree of independence as to how different practices organise their services. However the overall flavour of General Practice tends to be retained whatever profile and working arrangement the practice has. It is very hard to define what “good general practice” is - we hope you will be able to draw your own conclusions during this course and discuss your thoughts with your GP tutor and the tutors in the seminars.

Until April 2005 all GPs were required to provide adequate access to patients during surgery hours and also an emergency service 24 hours a day, 365 days a year as part of their defined contractual responsibilities. However, since the 2004 GP Contract most GPs have taken the option then made available to opt out of providing full 24-hour cover and hand over the responsibility for out of hours care of their patients (ie between 6pm – 8am on weekdays and throughout weekends and bank holidays) to the local Primary Care Trust (PCT).

5

Referrals from primary to secondary care in this country are made predominantly by general practitioners. GPs have been termed ’gatekeepers’ to the NHS. This implies their role in protecting specialist services from inappropriate demands, and on occasions protecting patients from unnecessary (often costly) investigations or interventions. The vast majority of problems presented to GPs will be managed within the practice. Of any 100 problems presented to GPs, on average no more than ten will be referred on to a specialist for their assessment and advice. This contrasts with other countries which do not have such a welldeveloped general practice system. There, patients may self-refer to one or many specialists.

Many investigations may be performed and the overall cost of health care to the individual and/or society may be much greater.

If there is one clinical task for all GPs which predominate, it is that of assessment. How ill?

How urgent? How many problems? Which matters most? Can a diagnosis be made? What might be the outcome? What sort of management? Can I manage alone? Who else is being affected? How much time can I spend on this problem as I have many other patients besides?

There are many opportunities within general practice for detecting illness at an early stage.

The potential and real effects of illness on a patient and those around them are generally best recognised within primary care. Illness and recovery affect more than the medical dimension to peoples’ lives - as shown in figure 2 physical

Fig 2: The holistic model showing how illness affects different dimensions of the sufferer’s life psychological social

The GP recognises the effects that illness has on the patient - and sees that the patient lies within the intersection of the above three regions. The broad scope of the GP, the contact over a longer period of time and familiarity with the patient in a variety of situations forms the basis for personal doctoring.

NHS changes in 2013

In July 2010, the Secretary of State for Health published the White Paper ‘Equity and

Excellence: Liberating the NHS’. It set out a number of changes to the way the NHS is structured and the way that care for patients is managed. The main changes are that:

Groups of local GPs and other clinicians (known as Clinical Commissioning Groups) will plan and buy most of the health care for the people in their area. This is known as

‘commissioning’. Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) will be in charge of real budgets for their area. The new arrangements will be very different and mean that GP groups are in charge. Strategic health authorities will be abolished by April 2013 and primary care trusts (PCTs) will formally hand over their commissioning responsibilities to GPs by April 2013.

6

A new national NHS Commissioning Board will allocate money to GP groups. The Board will also be in charge of commissioning dental, pharmacy, optometry and some specialist services.

Responsibility for health improvement – to promote good health and prevent illness, will be handed to local councils. A new body, called Public Health England will be created to help improve public health and reduce health inequalities.

Each local council area will have a HealthWatch, part of a national network of organisations that can look into complaints and scrutinise the performance of local health and social care providers.

All NHS hospital trusts will become foundation trusts, or become part of foundation trusts by 2013/14.

2. The Content of General Practice

Throughout the UK GPs on average have around 1,745 patients on their list. 70% of these patients will consult their GP at least once a year, and 90% will consult their GP at least once within a five-year period. The average length of consultation rose from 8.33 minutes in 1990 to 11.7 minutes in 2007. More recent data is not available but it is generally felt that this length has continued to increase. The national average consultation rate per person is 5 consultations per year (6 for women, 4 for men) Around 261 million GP consultations take place each year in the UK. This is equivalent to about 740,00 people (approx. 1.3% of the population) per day consult a G.

Government targets for “advanced access” have ensured that patients have fast access to

GPs and other health professionals in primary care. In 2014 97% of patients could see a GP within 2 working days

The reasons for patient consultations can be analysed in various ways. Table 1 shows a breakdown according to disease/system but many consultations will be for unclassified problems and about one in five will be for ’non-illness’ reasons - e.g. medical certificates, screening procedures, forms etc. Prevention of illness within General Practice now accounts for around 25% of the general practice workload.

Table 1. Types of problems presenting to GPs in order of frequency

Disease/ condition

Number of patients consulting per year (x 1000)

1 Respiratory system

2 Musculoskeletal system

13876

9937

3 Skin

4 Circulatory system

9775

8047

5 Genitourinary system

6 Digestive system

7 Injury and poisoning

6738

6476

5832

8 Infectious Diseases 5496

9 Mental Health and behavioural disorders 5270

10 Eye problems

11 Ear problems

4025

4007

12 Endocrine and metabolic problems

13 Nervous system

14 Neoplasms

15 Blood disorders

16 Pregnancy

17 Congenital anomalies

3986

3012

1500

651

348

309

18 Perinatal conditions 59

Source: Office of Health Economics. Compendium of Health Statistics 15 th

Edition 2003/4

7

3. Organisation and Finance of General Practice

3.1

The General Practitioner's contract (please also see 3.4):-

The GP Principal is an “independent contractor”, i.e. a self-employed person who has entered into a contract of services with the NHS. As independent contractors, GPs have considerable freedom as to how they run their practices. This freedom in turn carries administrative and financial responsibility for running the business of the practice and responsibility for the clinical services provided.

3.2

Doctors' Availability to Patients:-

Under their terms of contract General Practices are responsible for their own patients between 0800 and 1830 Monday to Friday. This responsibility can be shared amongst doctors within the practice. Until April 2004 all GP Principals were responsible for providing medical services for patients 24 hours a day, every day of the year.

Since April 2004 however, GPs have had the option to hand over responsibility for out-of-hours care (during evenings, nights, weekends and bank holidays) to the local primary care organization (PCO).

3.3

The Organisation of General Practice:-

There is enormous variation in GPs interests, premises and practices. Some GPs work outside the NHS, e.g. in Occupational Medicine, insurance etc. Some GPs are trainers, i.e.

selected and paid to train GP Registrars during their vocational training period.

Approximately 95% of practices are now computerised.

Currently the central feature of health care organization at a local level in England is the

Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG). These units have a responsibility for the health care of a large population (60-100,000) and the provision of a wide range of services.

3.4

General Practitioners' Pay under General Medical Services (GMS)

GPs are paid a gross income by the NHS out of which they meet their practice expenses, including staff salaries and the cost of providing surgery premises. Individual GPs receive greatly varying amounts of net income depending on the particular circumstances of their practices. The Average Income for GPs is negotiated with the Government each year by the

Independent Review Body.

Practices are also paid on the basis of providing 3 types of service – essential, additional and enhanced:

Essential o Every practice will provide essential services. This covers day-to-day work of general practice, looking after patients during an episode of illness, the general management of chronic disease and the non-specialist care of patients who are terminally ill.

Additional o Most practices will offer a range of additional services.

This covers areas such as contraceptive services, maternity services excluding intra-partum care, child health surveillance, cervical screening and some minor surgery.

Enhanced o These are optional and come in three types ie Local, National or Directed enhanced services. In essence they are specialised services which the CCG contracts particular practices to provide, at extra remuneration, to cover their own patients and also and those of other practices in the PCT area.

8

Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)

In addition to the above a new source of income introduced under the new GMS contract lies in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). “QOF points” are available to each practice for achieving a variety of quality standards and every point can be translated into income for the practice.

Points can be scored in any or all of four areas:

Clinical

Organisational

Additional services

Patient experience

19 areas are currently specified for Clinical QOF points. These were selected because there was good, UK-wide evidence of the health benefits likely to result from their inclusion in the framework. In addition, their inclusion was reinforced by the fact that responsibility for ongoing management of the disease is principally that of the GP and primary care team.

In the process of deciding which categories to include, some illnesses are left out even where there is good evidence because of the need to have reliable and measurable successful outcomes that were amenable to computerised scrutiny, in keeping with a high trust model of monitoring.

The clinical areas included in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (2013) are as follows:

Atrial fibrillation (AF)

Coronary heart disease (CHD)

Heart failure (HF)

Hypertension (HYP)

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD)

Stroke and transient ischaemic attack (STIA)

Diabetes mellitus (DM)

Hypothyroidism (THY)

Asthma (AST)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Dementia (DEM)

Depression (DEP)

Mental health (MH)

Cancer (CAN)

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Epilepsy (EP)

Learning disabilities (LD)

Osteoporosis: secondary prevention of fragility fracture (OST)

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Palliative care (PC)

For details of clinical QOF see: http://www.bma.org.uk/employmentandcontracts/independent_contractors/quality_outcomes

_framework/index.jsp

9

Personal Medical Services (PMS)

Not all general practitioners work under the General Medical Services (GMS) system. A second model of payment called Personal Medical Service (PMS) has been taken up by some practices.

PMS pilots were introduced to explore different ways of contracting for general medical services. The intention was to address local service issues and pilot new ways of delivering and improving services by allowing local flexibility.

Aims of PMS

Various aims have been cited and these include:

Promoting consistently high quality services

providing opportunities and incentives for primary care professionals to use their skills to the full

providing more flexible employment opportunities in primary care

addressing recruitment and retention problems in respect of GPs

reducing the bureaucracy involved in the management of primary care provision.

3.5

GP Commissioning

“Commissioning” is a term used variably within the NHS. For some, it is simply the process of purchasing services from providers by contract; for others, it includes the planning and design of integrated care pathways. GP Commissioning involves the devolution of some or all of these commissioning responsibilities from PCTs to individual or groups of general practices.

GP Commissioning is a key part of the Government’s strategy for improving the NHS. It aims to shift the focus of the NHS more towards prevention, moving more services – like diagnostics, minor operations and other treatments – out of hospital and ensuring all communities get the services they need. The logic is that by giving GPs the responsibility for local commissioning they will act more cost effectively, analysing the need for hospital care and redesigning services across the hospital-community interface. PCTs are now encouraging all their practices or localities to take on budgets for commissioning community health services and secondary care on behalf of their own populations.

GPs vary in their views on this development. While Practice Based Commissioning is likely to deliver a number of benefits for patients and local health economies, there is a risk the initiative will also induce a range of negative outcomes.

Likely benefits of GP Commissioning include:

A lowering in elective referral rates to hospitals

Reduced emergency related occupied hospital bed days

Shorter waiting times for emergency treatments

Improved co-ordination of primary, intermediate and community support services

Better engagement of GPs in the commissioning and developing integrated care pathways

Likely negative effects include:

Reduced patient satisfaction

Increased management costs

Reduced coordination of care delivery

Decreased cooperation with secondary care

We recommend you ask your GP tutors their views on GP Commissioning and what local arrangements are being implemented to implement this process.

10

3.6

Types of Practice Premises

GP Premises may be:

Part of doctor's residence - usually long-established single-handed or 2 partner practice, still found mainly in some rural areas but becoming rare, especially in cities.

"Lock-up" surgery - small “shop front” premises rented by 1-2 doctors usually in poorer areas of inner cities. Doctor may live a long way away; premises only open during surgery hours. Such surgeries have been gradually phased out by Primary Care Trusts and are now rarely seen.

Adapted premises - residential building in suburban area (e.g. 3 bedroom house), owned and converted for use as practice premises for multi-doctor practice. Some may have resident caretaker in upstairs flat. Open during surgery with ancillary staff present during most of the day.

Purpose built group practice premises - usually built for, and owned or leased by medium to large group practice (4-8 GPs) with adequate accommodation for employed and attached ancillary staff.

Health Centre - usually large purpose built premises, provided by Primary Care Trust with surgery suites for GPs (6-12 or more) who may be practising in groups, pairs or singlehanded within the Health Centre, or there may be a practice manager for the whole centre with all staff appointed centrally. Usually one or more fully equipped treatment room for practice or PCT employed nurses - Health Centres may also includes all facilities normally housed in a PCT Health Clinic.

Health Clinic - serves geographical catchment area - base for PCT employed staff eg district nurses, midwives, health visitors, school dental and medical services, speech therapy, audiometry, chiropody and other local services, ante-natal clinics, baby clinics, family planning, well woman clinics. Does not contain any accommodation for general practice.

Polyclinic: Following Lord Darzi’s Healthcare for London Review in 2007 the term

“polyclinic” was widely used to describe proposals for the development of large community healthcare facilities intended to provide a wider range of services than offered by most GP practices. A number of such centres have subsequently opened but the term polyclinic has generally been rejected. It is likely that different models will be used in different areas.

This may be an interesting topic of discussion with your GP tutors in relation to local arrangements in their area.

3.7

The Representation of GPs

GPs are elected to Local Medical Committees (LMC) and LMCs in turn elect GPs to the

General Practice Committee (GPC).

The GP is represented by means of the GPC in negotiations on terms and conditions of service with the government. The GPC is one autonomous "craft committee" of the British Medical Association.

3.8

The Primary Health Care Team (PHCT)

This consists of those members whose work entails caring for patients in a primary care setting.

General Practitioners (self-employed, contracting their services to the NHS via the HA)

Practice Nurses (nurses directly employed by the practice)

District Nurses (attached to the practice, usually employed by the Community Trust)

Health Visitors (usually employed by the Community Trust)

Receptionists, clerks, secretaries and practice managers (all employed by the practice)

Midwives (employed by the Community Trust)

Others e.g. social workers, counsellors, chiropodists, physiotherapists, community psychiatric nurses, (employed by a variety of arrangements)

11

Thus, we can see that though different members of the PHCT work together, they have different employment arrangements and different areas of responsibility and accountability.

3.8.1

Staff employed by the GP

The amount of money available for staff reimbursement is now limited by the Government; this percentage now varies between HAs and may be very low. Training usually is based on the job though some courses are now available.

Clerical/Administrative

Receptionist

Basic duties:-

receiving and directing patients

answering telephone

making appointments

taking requests for visits and repeat prescriptions

getting out and returning patients' records

filing correspondence and reports

transference of records between practice and HA

arranging hospital appointments and admissions

writing out repeat prescriptions (in some practices)

Secretary

Shorthand/typing of letters and reports. If no Practice Manager, may also perform some of duties listed below.

Practice Manager (usually in large group practice or health centre).

hiring of other ancillary staff

wages, tax and NI records of employed staff and doctors

keeping of accounts and financial records

preparation and submission of financial claims to HA

co-ordination of work of doctors and other staff, on call rota, weekend duties, holidays

care of premises - organising attendance of builders, plumbers, decorators, etc.

Nursing Staff

Practice Nurse

Employed by GP. Training; usually a Registered General Nurse (RGN) but occasionally an

Enrolled Nurse (General) (EN(G)).

Based in practice premises and should have own treatment room.

Duties may vary according to experience, training and practice arrangements but likely to include;

new patient checks

chronic disease management (eg asthma, hypertension, diabetes)

advising on minor illness

family planning

running cervical screening programme

cardiovascular risk assessment

antenatal care

injections and vaccinations

dressings

taking blood and urine samples, swabs

testing urine

monitoring weight and blood pressure

ear syringing

preparing for and assisting with minor surgery.

may take ECGs

may act as a chaperone for the doctor

12

In some practices the practice nurse may make visits to patients at home for example to do ear syringing, take samples, make preliminary assessment where visit is requested or do the over 75 check which all GPs should offer annually to their elderly patients. They may also help with reception duties in small practices when one of the reception staff is on holiday

(e.g. filing, repeat prescriptions, etc.) and give telephone advice to patients.

Nurse Practitioner (NP)

The nurse practitioner is a relatively new post which has specific training. Nurse practitioners are independent clinicians who are trained beyond pure nursing roles and have some responsibilities for limited diagnosis and management of conditions in their own right. There is a limited list of medications and appliances from which NPs may prescribe. NP posts are being developed in many different settings - not only general practice (such as A&E

Departments and Family Planning Clinics).

Other Clinical Staff

There may be a variety of other clinicians who hold sessions within a GP surgery.

Counsellors, complimentary practitioners (such as acupuncturists, osteopaths, hypnotherapists), consultants providing outreach sessions, all may do sessions. These practitioners will all have unique arrangements with their particular practice. In some cases the patient may pay them a fee, and the practice charges the clinician for the use of the room, heating etc. Another arrangement is that the practice itself may purchase the practitioner’s skills and provide these for the patient, with or without HA reimbursement. This may be how an under spending fund-holding practice may chose to spend the money it saves in one financial year.

A relatively recent development in general practice is the role of Healthcare Assistant

(HCA). The role of a healthcare assistant is, after appropriate training, to support medical and nursing staff by carrying out a range of basic clinical procedures eg measuring patients’ height, weight, blood pressure, urine testing etc, as well assisting practice nurses in the day to day running of clinics and treatment rooms. They may sometimes be trained in phlebotomy also.

3.8.2

Staff usually employed by the Primary Care or Community Trust

District Nurse (sometimes called Home Nurse or Community Nurse)

Training; RGN and may have done a 1 year course in district nursing. Based in a Health

Authority Clinic or Health Centre. May be attached to a group practice or to two smaller practices for liaison purposes, but works mainly in patients' homes.

District nursing duties depending on policy of particular Community Trust may include:

general nursing care of elderly, handicapped, acutely ill or post operative patients

dressing of let ulcers and wounds

regular injections -eg insulin, cytamen, modecate

changing of catheters, management of incontinent patients

enemas/manual removal of faecal impaction

administration of medicine, eye drops etc. to elderly or disabled patients

supervision of treatment of family for head lice, scabies etc. (sometimes done by health visitor)

immunisations, occasional family planning clinics.

Her or his duties in the Health Centre may be to perform similar duties to a Practice Nurse

Specially trained district nurses may take responsibility for stoma care, mastectomy counselling, home care of terminally ill patients, drug or alcohol work. Additional assistance may be provided by bath attendant (may be EN(G)) and night sitters.

13

Health Visitor

Training: RGN, Registered Midwife (RM) or obstetric course, and registered as Registered

Health Visitor (RHV) (1 year course). Based either in local authority clinic with responsibility for a geographical patch, or attached to a general practice or health centre. The function of the HV is to promote preventive Health Care/Health Education. Duties may be as follows:-

At Home:

Routine and regular home visiting of babies, pre-school children, and the elderly. Statutory duty to visit new babies at home at 10 days. Care of families with special problems e.g. one parent families, socially deprived families, families with physically or mentally handicapped child, child on “at risk” register (suspected non-accidental injury), family with patient who is violently alcoholic, mentally ill etc., where counselling required for bereavement, marital problems etc.

In the Clinical or Health Centre:

Mother craft classes

Baby clinics, involving:

immunisation

development assessment

advice on care and feeding

initial advice on behavioural problems, e.g. tantrums, enuresis etc.

As Information Source:

In Schools:- talks or advice on health education for teachers or pupils (e.g. hygiene, sex education)

For clients: - e.g. welfare benefits, self help groups etc.

Care of the Elderly (may be specialist geriatric HV): may be involved in the annual surveillance of patients >75 years.

Also:

supervision and liaison with GP

screening for illness/disability

advice on services, e.g. meals on wheels, chiropody, home help, hearing aids

arrangement for admission to geriatric unit or part III accommodation.

Midwife

Training; RM usually RGN also. Usually based in Health Authority Clinic. May attend health centre or group practice on specific days for ante-natal clinic. Main duties:

visits patients at home prior to accepting domiciliary booking

sees patients for ante-natal care at clinic or in practice

attends confinement and gives postnatal care for two weeks after birth

post natal care for "planned early discharged" patients after hospital confinement.

Community Psychiatric Nurse (=Community Mental Health Nurse)

Training - Registered Mental Nurse (RMN) with or without other general nursing qualifications. Usually based in local psychiatric hospital - works in the community, visiting and supervising:

patients discharged from hospital

outpatients between hospital attendances

patients not under hospital care, at request of GP.

CMHNs May hold sessions within the GP surgery and accept direct referral from the GP for counselling.

14

3.8.3

Staff usually employed by Social Services Department of the Local Authority

Social Worker

Training and Qualifications; some university graduates, all have college based Certificate of

Qualification in Social Work (CQSW). Based mainly in area offices. Occasionally attached to health centre - degree of liaison with GP varies widely. Hospital based social workers liaise with GPs and community colleagues as necessary.

Core duties:

Counselling and care work with individuals and families with social problems (e.g.

delinquency, school refusal, financial problems).

Assessment and feedback to others in primary care team.

Statutory duties with regard to provisions of Mental Health Act and care of children at risk.

Access to resources provided by local authority for handicapped, elderly and needy, e.g..

telephones, housing adaptations, aids for disabled holidays and outings.

Home Help

Domestic staff sent to homes or elderly or handicapped people or families during a crisis period. Duties mainly include shopping and housework. Often act as contact between patient and GP, collecting prescriptions for patients and reporting back any sudden change in patient's circumstances. Often, the patient has to pay a small amount towards having a

Home Help.

15

Core GP Seminar 2

What goes on in General Practice?

Aims :

Objectives:

To consider the content of general practice, the sorts of problems which present and the strategies available to deal with them.

By the end of the seminar you should have:

1. understood the broad categories making up the clinical content of general practice

2. understood the pattern of problems which commonly present to

GPs

3. appreciated the critical importance and some basic theory of the

GP consultation.

4. become familiar with the common clinically related forms and paperwork in general practice and how to use them

References : Simon et al. Oxford Handbook of General Practice. Oxford University

Press 2014

Cartwright S & Godlee C. Churchill’s Pocketbook of General Practice.

Churchill Livingstone 2008

Stephenson A. A Textbook of General Practice. Hodder Arnold, 2011

Booton et al. General Practice at a Glance Paperback Wiley-Blackwell,

2012

16

Notes for Core GP Seminar 2

The GP Consultation

As students you will have seen many consultations taking place between doctors and patients; on the wards, in the outpatient department and in the GP setting. You are already conducting consultations yourselves in your clinical attachments. Patients in your hospital and GP attachments so far however have in general been highly selected and likely to present their symptoms in a relatively well-organized manner. Things are different in a normal general practice surgery where people often present with apparently unconnected and undifferentiated problems. The consultation in general practice is thus different from the direct history-taking model you have tended to use so far and requires some new skills on your part.

We recognise that you have already learnt a lot during your training so far about the importance of communication skills in medicine. Part of this session is therefore intended to help you revise and build upon your existing knowledge and skills and apply them in the different environment of general practice.

In order to make sense of the problems patients bring to us we must be aware not just of their presenting complaints but also how the behaviour and experience of both doctor and patient affect our interactions. Although the doctor, in most cases at least, controls the character of the consultation, it is possible for the patient to take an equal part in the process if what has been called a "patient-centred" approach is used. This involves the doctor using such methods as open questions, active listening, challenging and reflecting in order to allow patients to express themselves in their own way. The other extreme is a “doctor-centred” approach where the doctor dominates the interview using direct, closed questions, rejecting the patients’ ideas and evading their questions.

Patient-Centred uses patient’s knowledge and experience

Fig 1.Approach to consulting (from Byrne & Long [1976)

Doctor-Centred uses doctor’s skill and knowledge

There is obviously a spectrum between the heavily doctor dominated consultation to the completely patient dominated one but keeping the patient centred approach in mind you will find that you can actually draw out more useful and relevant information in a shorter time, and also, both you and your patient feel more satisfied at the end of the consultation.

17

Stott and Davies in 1979 described four broad areas which the consultation in general practice should aim to cover. These are shown in Fig 2.

A

Management of the presenting problems

(e.g. the sore throat)

C

Management of Continuing

Problems

(e.g. the previous history of asthma)

B

Modification of help-seeking behaviour

(e.g. educating patient as to appropriate use of resources)

D

Opportunistic Health Promotion

(e.g. advice on smoking and weight reduction)

Fig 2. The potential in each primary care consultation (Stott & Davies 1979)

When you start seeing patients at your practice try to consider these four areas. You will find that even in apparently straightforward consultations there are usually issues to be covered in each one.

Five tasks of the consultation - The Calgary-Cambridge Model

Here are some tips, based on the five tasks of the consultation sometimes known as the

Calgary-Cambridge Model. Thinking in terms of this simple structure will almost certainly help you and your patients get more out of each consultation. The tasks are

1. Initiating the consultation

2. Gathering information

3. Building the relationship

4. Giving information - explaining and planning

5. Closing the consultation

1.

Initiating the session

The introduction should be welcoming. Put the patient at ease. The relationship you form now affects the likelihood of a positive outcome.

2.

Gathering information

A.

Determine the reason why patient has come. Explore their ideas , concerns and expectations about their problems. Listen carefully then ask any specific questions you feel are necessary Ask:

18

3

“What do you think might be wrong?”

“Are you afraid of anything in particular?”

“Why have you come today?”

“What are you hoping I can do to help?”

Physical examination is a key element of your” information gathering”

Building the relationship

This means using your communication skills to demonstrate empathy and understanding. Try to appear confident. Use appropriate non-verbal behaviour. Think about taking notes or using the computer in a way that does not exclude the patient.

4

5

Giving information

When you have made an initial assessment, explain things to the patient at a level and in a language appropriate to that individual. By using simple language you will achieve greater understanding and therefore better compliance with any advice or treatment you recommend. Allow opportunity for questions and be prepared to say if you don’t know the answers and how you will find out more.

Closing the session

Getting the ending of the consultation right is as important as getting off to a good start. Try to check that you and your patient have understood each other and that you have given an opportunity for questions to be asked. Remember that not all consultations have to end with a prescription or a referral. Involve the patient where possible in decision making about management and any plans for follow-up.

The consultation is the central process in general practice and yet studies that have measured such things as patient satisfaction, patient recall and patient compliance, have shown that its potential is often not fully realized. This is why a lot of research has been done to try and untangle what goes on in the consulting room and how techniques might be improved. Several models have been suggested to try and analyze the consultation and the nature of doctor-patient communications. Space does not allow a review of all these ideas here but some key references are listed below.

References

Balint M. (1985) The Doctor, His Patient and the Illness. London: Tavistock Publications.

Byrne P., Long B. (1976) Doctors Talking to Patients. London: HMSO

Kurtz SM & Silverman JD: The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organising teaching in communication training programmes

Medical Education 1996 (30) 83-9

Neighbour R (1999) The Inner Consultation

Pendleton D. (1984) The Consultation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

19

Core GP Seminar 3

Common problems in General Practice: an afternoon surgery

Aim :

Objectives :

References:

To consider the clinical content of general practice by discussing the management of some common problems as might present on any day in the surgery.

By the end of the seminar you should have:

1.

Worked through a series of short case vignettes with the group.

2.

Gained knowledge of the management of some problems which are common in general practice but discussed little in the hospital setting

3.

Developed your ability to think critically about some of the factors which influence our practice.

Birtwistle J, Everitt H, Simon C, Stevenson Brian Oxford Handbook of

General Practice. Oxford University Press 2002

Cartwright S & Godlee Churchill’s Pocketbook of General Practice.

Churchill Livingstone 2003

Forte V, Hopcroft K Symptom Sorter. Radcliffe Medical Press 2003

20

Core GP Seminar 4

Chronic Care in General Practice

Seminar Aim: To explore the impact of chronic illness on patients, families, carers and the caring services and the role of the GP and Primary Health

Care Team.

To understand some theoretical concepts studied in chronic illness and care.

Objectives: By the end of the seminar you should have:

1.

discussed the physical, social, psychological, and financial implications of a chronic illness for a patient and their family.

2.

understood and appreciated the impact of disability on a person’s life.

3.

appreciated the experience of the carers of a person with chronic illness

4.

understood the role of the Primary Health Care Team including the

GP and how this may alter as illness progresses.

5.

Understood the issues involved in supporting people with chronic illness in the community, the resources available and the practical aspects of team working

6.

Understood some theoretical concepts used in the study of chronic illness and care.

7.

understood the requirements for preparing your chronic care essay which forms the written part of your in-course assessment for the

Core GP (see below)

Seminar content

Part 1 A patient’s story of a chronic illness (presented as an MEQ on overhead slides) as it evolves and the interventions of the PHCT and caring services to stimulate thought and discussion.

Part 2 A discussion of some of the key theoretical concepts arising from studies of chronic illness and care.

Part 3 Some short videos of carers talking about their experience to stimulate a discussion of issues of caring.

21

Preparing Your Chronic Care Essay

As the written component of the in-course assessment in General Practice each student will carry out a case study of a patient from their practice with a chronic illness and/or disability.

This will involve interviewing the patient and a major carer in their own home, discussing the management with the GP Tutor and preparing a written report for marking by the GP Tutor.

The essay should be between 1000 and 2000 words long.

Guidelines for preparing the essay

You should approach your GP tutor early on in your Core GP Attachment in order to select a patient with a chronic physical disability who is willing to talk with you at home. Patients with a wide range of conditions may be suitable e.g. arthritis, heart disease, asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, stroke, chronic bowel disorders, multiple sclerosis or other chronic neurological conditions etc. You should have the opportunity to meet family members and other lay and professional carers. More than one visit may be required.

Based on your meeting with the patient and discussions with any other people involved in their care, you must write an essay based on the patient’s and, where relevant, any carers’ experiences of living with a chronic illness or disability. The seminar should have primed you for the main issues in the patient’s, family’s and carer’s lives; past, present and future, physical, psychological, social and financial. You should also discuss the case with your GP

Tutor before writing the essay.

The essay should:

include the Patient’s story written preferably in the first person. This is to demonstrate your perception and understanding of the patient’s view of the progression of the illness, its impact on their life, current situation and how they cope and the future outlook. This is not meant to be a medical case history but is written from the patient’s own viewpoint and should demonstrate their own character in the writing. We recognise that some students feel uncomfortable using the first person like this but commend you to try on this one occasion as many of your colleagues to say that they do find this helps them think about the patient’s view in a different way.

include a view written similarly from a carer’s point of view (where a carer is available)

be longitudinal, including the history, present situation and future outlook

be comprehensive, including the condition and its management, the disabilities arising from it, and the social and psychological consequences for the person and his/her family and carers

demonstrate direct knowledge of the services and resources contributing or potentially contributing to the care of people with chronic disability in the community.

Conclude with a summary of the case from the student’s point of view, discussing what has been observed, learnt and including any suggestions for improvements to the patients care and planning for the future. The role of the GP should be included in this summary. The student is encouraged to take a critical view of the situation and to draw some general conclusions from what has been observed. Some relevant mention of theoretical concepts used in discussion of chronic illness and care will be expected.

The essay must be handed in to your GP tutor by the end of Core GP week three so that they have time to mark it and provide feedback. The Tutors’ grade will be based on a structured marking scheme and will be taken into account towards the overall assessment for your GP clinical attachment. You should also email or send a copy to

Sandra Gerrard in the Department of Primary Care, Royal Free Campus

( s.gerrard@ucl.ac.uk

) by the final day of the attachment.

22

Core GP Seminar 5

Introduction to Occupational Medicine

Aims: To develop an understanding of Occupational Medicine and the role it encompasses in both clinical medicine and the world we live in.

Objectives: By the end of this session, you should be able to:

1. Describe what Occupational Medicine is.

2. Describe why Occupational Health is important for both the employee and employer.

3. Understand the importance of the new Fit for work Service.

4. Understand the main reasons for sickness absence in the UK.

5. Describe the basics of Health and Safety Legislation in the UK.

6. Explain the difference between a Hazard and Risk.

7. Name some examples of work related health problems.

8. Understand how to take a concise occupational history and assess fitness for work.

9. Understand how to provide an opinion on Disability Legislation.

10. Understand the implications of ill health on driving.

11. To know how to enter a career in Occupational Medicine.

Preparation:

Please choose an example of a patient you have seen in general practice or in a hospital setting where work was an important feature requiring medical advice or intervention. Think about the main features of the case (e.g. age, sex, job, reason for attending and relevance to work) and be prepared to discuss it during the teaching session. Was the sickness or ill health due to health impacting on work or work affecting health?

Further reading

1. DVLA: Drivers and Vehicle Licensing Agency, www.dvla.org.uk.

2. Faculty of Occupational Medicine, www.fom.ac.uk.

3. HPA: Health Protection Agency, www.hpa.org.uk.

4. HSE: Information about Health and Safety at Work, www.hse.gov.uk.

5. Society of Occupational Medicine, www.som.org.uk.

6. ABC of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 3 rd edition. Editors David Snashall &

Dipti Patel. BMJ Publishing Group 2012.

7. Atlas of Occupational Health and Disease. Nerys R Williams and John Harrison. Arnold

2004.

8. Fitness for Work: the medical aspects 5 th edition. Editors Keith Palmer, Ian Brown &

John Hobson. Oxford University Press 2013.

9. Occupational Health (Pocket Consultant) 5 th

Edition. T.C. Aw, K, Gardiner & J.M.

Harrington. Blackwell Publishing 2007.

23

Notes on Occupational Medicine

Occupational Medicine is a branch of medicine, which is concerned, with the effects of health on work and work on health.

Health and Work

Work is a central part of most people’s lives. Work defines a person, determines standards of living, social networks and places to live. Work therefore has a tremendous potential to enhance life, or to damage health. Whenever work has the potential to adversely affect health, it is necessary to identify the hazards, evaluate the risks they pose and take steps to minimise these risks as far as reasonably practicable. When an individual’s health problem impacts on their ability to work (whether through poor performance, sickness absence or unemployment), it is important that return to work, rehabilitation or access issues are addressed to enable individuals to reap the health benefits that being in work confers. (See

Waddell and Burton 2006. Is work good for your health and well-being?)

All clinicians need an awareness of the possible role of occupation in their patients’ illnesses

– both in causation and in modifying the impact of illness on life style. Physicians working in

Occupational Medicine focus on these issues. They have to consider not only individual patients but also groups of workers with similar exposures. Diagnosis extends beyond the individual to the working environment; and treatment, while often only symptomatic for the individual, has the potential for prevention of illness when applied to the workplace.

Many of the ‘classical’ occupational diseases, such as coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and bladder cancer in dye workers, are now uncommon in developed countries. The reasons for this include improved working conditions, strict control over the use of some toxic substances

(in some circumstances supported by specific legislation) and a decline in the manufacturing industry. This does not mean that occupational diseases are on the decline however; new technology brings its own hazards. Materials such as plastics can act as sensitisers causing contact dermatitis and allergic asthma; blood-borne viruses such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV pose a threat to health care workers, and the impact of psychological health and musculoskeletal problems at work are being increasingly recognised, now forming the majority of sickness related ill health.

It is important not to forget the latency of some occupational diseases, such of that in exposure to Asbestos.

Presentation of occupational disease

Work related ill health tends to present in the same ways as other conditions.

For this reason general practitioners and hospital specialists are likely to see as many patients with occupational disease as occupational physicians, if not more. The pathology of diseases is the same whether it is work related or not. The association with work may only become apparent by considering possible causes for a condition and eliciting the relevant history.

The timing of symptoms in relation to work may be a clue, as well as other colleagues presenting with similar symptoms.

The Occupational History

A brief occupational history should be a routine part of the history obtained from every patient. It gives an indication of the patient’s routine both inside and outside of work, and assists in the ultimate diagnosis and decision as to whether work is impacting on health and vice versa.

24

Assessment of medical fitness for work

This forms a large part of the workload of occupational health services. Such assessments are often made at the pre-employment or pre-placement stage; however the benefits of such assessments are controversial, unless there are for safety critical work such as Fire Fighting, or for Life Insurance purposes. Fitness to work may also be required during employment where concerns arise about recurrent or intermittent illness, behaviour problems, absenteeism or safety concerns present.

General Practitioners may also be required to assess their patients’ fitness for work, for example when asked for sick certification and issuing of the ‘fit note’.

In order to make fully informed assessments, it is necessary to consider the specific requirements of the job for which the patient is being assessed, the relevant aspects of the medical history, and the risks that the work may have for the individual, their colleagues, their employer and the public. The interaction of these factors is often complex and dynamic.

Expected Outcome of Seminar

This session aims to increase your knowledge of Occupational Medicine, making use of real life experiences, pictures and videos to create an interactive exciting seminar. No matter what speciality of medicine each of you choose in the future, the importance of Work, Health and Wellbeing is vital to ensure a return to work can be considered a positive clinical outcome. Lastly, the taught content with be assessed in your examinations, so attendance is highly recommended!

Dr Richard Peters

MBBS Curriculum Lead for Occupational Medicine

Department of Primary Care and Population Health

UCL Medical School

Royal Free Campus

Email: Richard.Peters@ucl.ac.uk

25

F

R

I

D

A

Y

R

S

D

A

Y

T

H

U

T

U

E

S

D

A

Y

M

O

N

D

A

Y

Year 5 General Practice Clinical Attachment

Also to incorporate 2 days of Child Heath in Primary Care – dates advised seperately.

(All seminars will take place in Seminar Rooms 1&2, department of Primary Care and Population Health)

WEEK 2 WEEK 3 WEEK 4 WEEK 1

0930 - 1000

Course Introduction

1000 - 1115

The Organisation of

Primary Care

1130 - 1245

What goes on in

General Practice

1345 - 1530

Common Problems in GP: an afternoon Surgery

In

Practice

In

Practice

In

Practice

In

Practice

In

Practice

In

Practice

In

Practice

W

E A

D M

Primary Care Seminars

0930 - 1100

Chronic Care in GP

1130 - 1300 N

E

S

D P

Occupational Medicine

A M

Y

Sport/Self-directed learning

All students in GP based Dermatology teaching (in dedicated dermatology teaching practices)

Sport/Self-directed learning

In

Practice

Sport/Self-directed learning

All students in GP based

Dermatology teaching

(in dedicated dermatology teaching practices)

Sport/Self-directed learning

In

Practice

27 SEPT

In

Practice

In

Practice

4 OCT

In

Practice

In

Practice

11 OCT

In

Practice

In

Practice

18 OCT

Vertical Module

Teaching

See Block Information

Pack

26

Year 5 Child and Family Health with Dermatology (CFHD)

CHRONIC CARE ESSAY – TUTOR’S ASSESSMENT

Your student should give you a copy of their essay by the end of the third week of the attachment. Having discussed the work with your student, please assess and grade the essay using the guidelines below and the marking table over page.

A proportion of essays will be re-marked within the department to monitor consistency in grading therefore students are required to email a copy to Sandra Gerrard once completed.

The essay should be 1000-2000 words long. The good student will have made an effort to carry out this work with enthusiasm and initiative and this should be reflected in the finished essay. The essay should draw out the physical, psychological and social aspects of the story, the caring arrangements and an understanding of how the Primary Care Team, social services and involved others interact. Ideally part of the essay should be written in the first person voicing the views of both the patient and a main carer. The student should be critical and sensitive and should draw out some original observations of their own.

Although the essay may not be written under these headings, the following elements should be present and some general pointers are given as to how to mark under each area. It may be helpful to tick the boxes below and give an overall grade over the page reflecting the majority of ticks.

Elements of the essay

The patient’s story

The Carer’s story

Role of Primary Care

Team

Student’s assessment of role of GP

Student’s assessment of the illness/ disability and the caring situation

Suggestions for improvements to current care and future possibilities

Reference to sociological concepts of chronic illness discussed in seminar

E = Fail

Scanty, or inaccurate. Maybe obviously taken from patient notes.

Absent: no obvious effort made.

Little or no reference to any members

Scanty- no real effort made to show much thought applied.

None or something impractical or irrelevant.

No reference to theoretical concepts.

D = Borderline

Accurate, complete. Maybe dry and matter-offact or written in voice unlikely to be that of the subject.

Present but not particularly illuminating.

At least two PHCT members mentioned appropriatelymaybe some confusion over roles.

Absent or scanty.

Superficial or obvious.

Has attempted, though may be immature or show misunderstanding

At least one sensible suggestion.

At least one mention of theoretical concepts.

C = At level expected

Fleshed out with empathy – clearly different from a medical “clerking”.

Recognisably the patient’s voice.

Adds real substance to the overall story.

PHCT members mentioned with their roles reasonably described.

Showing fair understanding.

A good overview showing a clear understanding.

Several suggested improvements to care. Future view may be limited.

One or two references to theoretical concepts in correct context.

B = Above expected level

Detailed and well written demonstrating student’s ability to

“get under the skin” of the subject.

Showing empathic understanding of issues of caring.

Demonstrating a good sound understanding of the individual roles and how they work together

(or not).

Good practical understanding showing perspective.

Some opinions voiced and a reasonable judgement formed on this situation.

Useful and practical suggestions and evidence of student looking into the future.

Several relevant references to theoretical concepts showing understanding of their significance.

A = Well above level expected

Unusually sensitively written and perceptive.

Empathic, detailed exploration of role and views of this carer.

A detailed discussion of the roles, boundaries, organisational and practical issues relating to the PHCT team showing real understanding.

Critically appraised.

An in depth critical appraisal of this situation drawing many specific points to illustrate general principles.

Mature and sensible discussion of possibilities now and contingencies for future needs.

Frequent, relevant and critical reference to theoretical concepts which illuminate the story.

27

Core General Practice Checklist

It may not always be possible to achieve all the items in this list but you should use it as a guide to discuss progress with your tutor around the mid-point of the attachment.

During the placement so far

— have you:

Tick

1. Observed and discussed tutor’s consultations and those of at least one other practitioner?

2. Conducted at least six consultations before the tutor interviews the patient?

3.

Observed during consultations whether:a diagnostic label is achieved?

the physical, psychological or social aspects predominates?

the problem is urgent or not?

4.

Identified three examples of the influence of social and psychological factors on the presentation, management and outcome of illness?

5.

Described the management of at least three common

acute

conditions and discussed these in the practice?

6.

Described the management of at least three

chronic

conditions and discussed these in the practice?

7.

Visited at least one patient with a chronic condition at home and produced a chronic care essay?

8.

Identified three examples of hospital referral (including one urgent one) and the factors which affected the decision and discussed these in the practice?

9.

Observed the work of receptionists?

10. Observed the work of a practice nurse?

11. Discussed a patient with a social worker?

12. Been on visits with a district nurse?

13. Been on visits with a health visitor?

14. Identified at least four examples of opportunities for health promotion and disease prevention?

15. Had some experience of out-of-hours general practice?

16. Received feedback from the tutor and offered it in return?

Comments:

28

Sample Certificate

29

30

Contact Details for Core GP1 course

Course Administrator

Sandra Gerrard

UCL Medical School

Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health

Royal Free Campus

Rowland Hill Street

London NW3 2PF

Tel: 020 7830 2599

Fax: 020 7472 6871

Email: s.gerrard@ucl.ac.uk

Course Lead

Dr Joe Rosenthal

Senior Lecturer in General Practice

Sub Dean for Community Based Teaching

UCL Medical School

Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health

Royal Free Campus

Rowland Hill Street

London NW3 2PF

Email: j.rosenthal@ucl.ac.uk

31