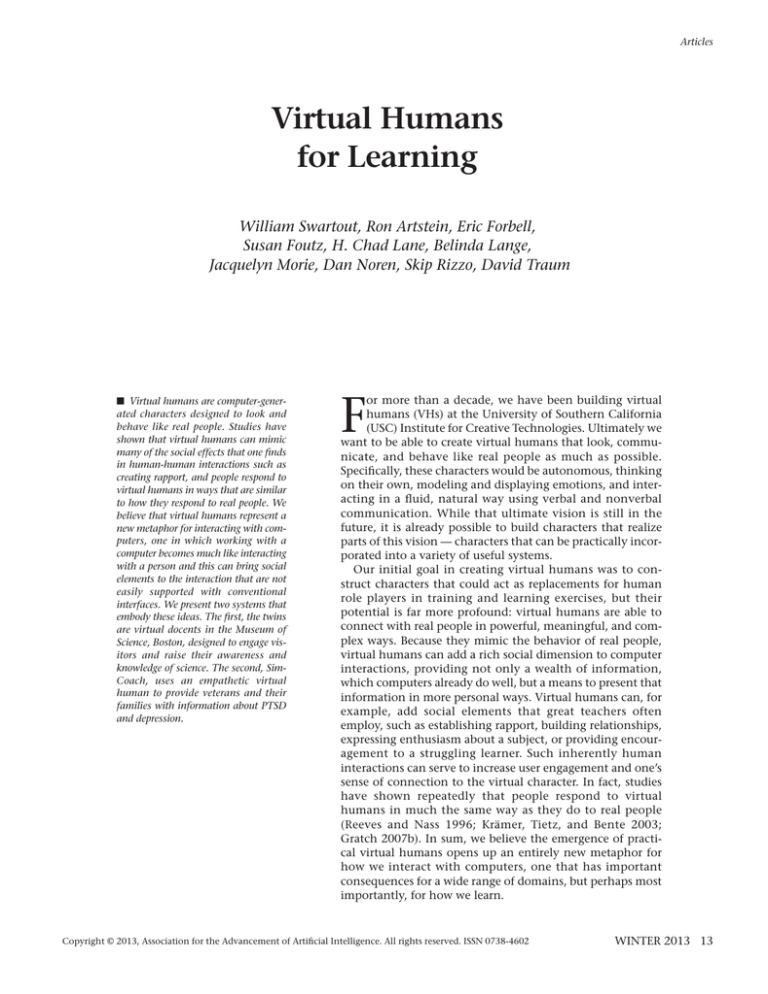

Virtual Humans for Learning

advertisement