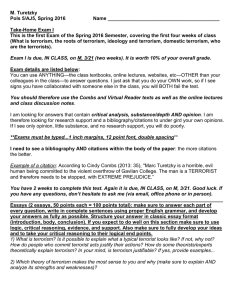

Homeland Security and the Rule of Law:

Methodology and Myth

Remarks by Dick Thornburgh, Former

Attorney General of the United States,

to The Dickinson School of Law Chapter

of the Federalist Society at Pennsylvania

State University

Dick Thornburgh

(202) 778-9080

dick.thornburgh@klgates.com

www.klgates.com

The rule of law today is under enormous stress worldwide and is indeed a subject

of considerable concern within our own borders. Threats to this cardinal principle

underlying our democracy deserve our constant attention, lest we fall prey to the threat

of disorder and chaos which afflicts so many areas of our world in this 21st century.

The rule of law is the linchpin in efforts to promote democracy and human rights

around the world and we dare not overlook its significance in the effort to harmonize

differences and promote social and economic growth worldwide as well as in our

United States.

Our world was changed completely by the events of September 11, 2001. On that date,

the ramparts of our fortress America were breached, not by an invading army or by an

alien enemy air armada, but by fanatic terrorists with no regard for innocent human

life, or indeed for their own. Their cowardly attacks that day on New York, Washington

and in the fields of Central Pennsylvania took the lives of some 3,000 innocent persons,

most of them going about their ordinary pursuits on that fateful day. This dreadful

assault on our country has obliged us to rethink many of our basic assumptions about

national defense and homeland security. We are now forced to confront threats totally

unlike those we have had to face in times past. But this nation and our people have

proved equal to the challenges of the past and we have no reason to suspect that we

will be tried and found wanting in responding now.

In devising a strategy for responding to these threats, one of the first considerations

we have had to deal with is the preservation of our own treasured rights and liberties.

Today, the United States continue to stand throughout the world as the prime exemplar

of the rule of law and of a democratic political system. We are the envy of many other

nations and their peoples for characteristics which, frankly, we all too often take for

granted. What we enjoy in our nation is looked on with covetous eyes by many of

the world’s people -- especially those still living under despotic rulers, fearful of the

knock on the door at night, unable to speak out against injustice, mired in poverty and

laboring within backward economies which are often corrupted by their leaders. Worst

of all, too many of the world’s peoples today are denied any means to peaceably effect

necessary changes in their political and governmental systems.

K&L Gates comprises approximately

1,700 lawyers in 28 offices located

in North America, Europe and Asia,

and represents capital markets

participants, entrepreneurs, growth

and middle market companies,

leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE

100 global corporations and public

sector entities. For more information,

visit www.klgates.com.

True, we must take note of the fact that, in times of stress, our constitutional principles

can be severely tested. The effort to balance national security and individual liberty

inevitably produces tension. The late Chief Justice Rehnquist once noted: “in wartime,

reason and history both suggest that [the balance between freedom and order] shifts

to some degree in favor of order -- in favor of the government’s ability to deal with

conditions that threaten the national well-being.”

And sometimes that shift runs to excess. History reminds us of the late 18th century

Alien and Sedition Acts which posed a genuine threat to freedom of speech and

association in the early days of our republic. During the Civil War, even our most

revered president, Abraham Lincoln, it must be remembered, felt obliged to suspend the

ancient writ of habeas corpus, a move many scholars today view as unconstitutional.

Following the end of World War I, the infamous Palmer raids scooped up hundreds

Homeland Security and the Rule of Law:

Methodology and Myth

of aliens in dragnets directed at so-called “radicals.”

And, during World War II, Japanese- American

citizens were taken from their homes and confined

for the duration of hostilities for no reason other

than their ethnic background, surely one of the most

shameful episodes in U.S. history.

So we must always be on the lookout for overreaction

in times of war or national emergency, when law

enforcement or our intelligence agencies may be

tempted to push the envelope of constitutionality too

far in defense of our nation. Care must be exercised

lest they cross the line into violation of our civil

rights and civil liberties.

I.

Today there is, I perceive, a broad consensus in

our nation about the need to fully empower those

to whom we have assigned the task of fighting

terrorism on our shores. Yet, we as a people have a

strong tradition of fearing centralized, secret police

power. This view is reflected in the National Security

Act of 1947 that created the Central Intelligence

Agency but expressly forbade the CIA from having

law enforcement authority. Memories of the Nazi

Gestapo were still very fresh in our minds in 1947.

Even seven years after the tragic events of September

11, 2001, we continue to face the need to develop

new techniques to deal with the threat of terrorist

activities. The American people rightly will not

accept a government that fails to “connect the

dots.” It is unacceptable that one federal agency

with information about, for example, terrorists’

planned use of weapons of mass destruction should

be prevented by law from sharing that information

with another agency that might be lacking that

very piece of the puzzle needed to thwart the

terrorists’ plan.

Important distinctions must be made between

the roles respectively, of law enforcement and

intelligence gathering in the effort to protect our

citizenry and our institutions from the menace

of terrorism.

•Law enforcement seeks legally admissible evidence

to prove a specific criminal offense in court before

a judge and jury;

• Intelligence gatherers, on the other hand, seek

enough information, whether legally admissible or

not, to thwart planned terrorist attacks.

• And these are not the same. One is designed to

punish those who have committed terrorist attacks

after the fact; the other is designed to prevent

terrorist attacks before the fact.

This is one of the principal reasons why cooperation

between the FBI and the CIA or other intelligence

agencies has sometimes been less than ideal in the

past. Grand jury testimony and information obtained

from court-authorized FBI wiretaps often could

not legally be passed on by law enforcement for

use by the intelligence community. By the same

token, intelligence information often could not be

transmitted for use by law enforcement for fear of

compromising the sources and methods by which

it was obtained, i.e., by jeopardizing the lives of

under-cover operatives or cooperating witnesses

or by disclosing highly sophisticated electronic

surveillance techniques in criminal trials held in

open court.

Particularly in the wake of September 11, however,

the American public would be understandably

outraged if told that the information in the files of

one government agency was not being fully shared

with other agencies when the stakes are as high

as they inevitably are in both the prevention and

prosecution of terrorist activities.

So the law was changed. In the fall of 2001, the

Congress by overwhelming margins passed the

USA Patriot Act, which sought to remove some

of the barriers to full cooperation. These changes

may still not prevent some very evil people from

escaping actual prosecution sometime in the future.

Legally admissible evidence may not, in fact be

available to convict them. But the changes will

certainly heighten the prospects of thwarting terrorist

designs and preventing potential widespread harm

and destruction. And I am confident that our criminal

justice process can reconcile the need for enhanced

homeland security and the observance of our basic

constitutional rights and liberties. After all, as United

States Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson once

observed, “our bill of rights is not a suicide pact.”

2

Homeland Security and the Rule of Law:

Methodology and Myth

II.

The task is a formidable one. Particularly since not

all our laws are accessible to the lay person. Take,

for example, Section 104 of the USA PATRIOT Act.

That section states, in its entirety:

Section 2332e of title 18, United States

Code, is amended —

(1) b y striking ‘‘2332c’’ and inserting

‘‘2332a’’; and

(2) by striking ‘‘chemical’’.

Without access to the existing statute, a reader cannot

tell that the old law permitted the Attorney General

to ask the Secretary of Defense for assistance in

the event of a chemical attack whereas the new law

applies to any weapon of mass destruction attack.

The USA PATRIOT does not read like a novel. To

understand it, a reader must have the Act in one

hand and all the laws it amended in the other. With

158 sections in ten titles as diverse as providing

monetary benefits to survivors of terrorist attacks

to changing the statute of limitations for terrorism

related offenses, the Act and its counterparts are

not an easy read and they have given rise to various

myths and misunderstandings. Let me deal with just

a handful.

Myth Number One: Time and again in the media I

hear it said that the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance

Act (FISA) is unconstitutional because it does

not require probable cause and is an attempt to

circumvent the Fourth Amendment itself.

This simply is not true The FISA statute itself

states plainly that before the Court may issue an

order authorizing electronic surveillance, it must

first find – and I quote -- “on the basis of the facts

submitted by the applicant there is probable cause to

believe that—“

• the target of the electronic surveillance is a foreign

power or an agent of a foreign power…;

• and each of the facilities or places at which the

electronic surveillance is directed is being used, or

is about to be used, by a foreign power or an agent

of a foreign power;

Indeed, even the most recent additions to FISA

enacted just this past summer, which extended the

FISA Court’s reach to the targeting for electronic

surveillance purposes of United States persons

outside of the United States require the court to

find that “there is probable cause to believe that

the target is –

• a person reasonably believed to be located outside

the United States; and

• a foreign power, an agent of a foreign power, or an

officer or employee of a foreign power.

The Supreme Court has never reached the issue, but

every Court of Appeals to consider the matter to date

has found FISA’s procedures authorizing electronic

surveillance to be constitutional. The Foreign

Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review examined

FISA after the statute was amended by the USA

PATRIOT Act and concluded in no uncertain terms:

“FISA as amended is constitutional because the

surveillances it authorizes are reasonable.” That is,

after all, what the Fourth Amendment emphatically

requires: “The right of the people to be secure in

their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against

unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be

violated.”

Myth Number Two: The Military Commissions Act

of 2006 (MCA), passed by Congress and signed into

law by President Bush in 2006 creates a system of

“Kangaroo Courts.” Not so. The Commissions may

be used to try only alien, unlawful combatants. The

MCA requires that an accused be given notice of

the charges and specifications against him and be

permitted to:

• present evidence in his defense;

• c ross-examine the witnesses who testify

against him;

• e xamine and respond to evidence admitted

against him on the issue of guilt or innocence and

for sentencing;

• be present at all sessions of the military commission

(other than those for deliberations or voting),

except when the accused persists in conduct that

endangers the physical safety of individuals or

disrupts the proceedings;

3

Homeland Security and the Rule of Law:

Methodology and Myth

• receive the assistance of counsel, both military and

civilian; and

• represent himself, if he so chooses.

Moreover, the MCA explicitly states, “[n]o person

shall be required to testify against himself at a

proceeding of a military commission,” and that

“[a] statement obtained by use of torture shall not

be admissible in a military commission under this

chapter, except against a person accused of torture

as evidence that the statement was made.”

The MCA does not permit the use of secret evidence

that the defendant and his attorneys are not permitted

to see.

All of these provisions are entirely consistent with

the rights granted our own citizens in the federal

district courts. The variances from our civilian

criminal courts found in the MCA are, I submit,

reasonable accommodations to the circumstances

of warfare.

For example, the MCA requires that the traditional

rules of evidence apply “so far as … practicable or

consistent with military or intelligence activities.”

The exception to the traditional rules is that the MCA

permits introduction of hearsay evidence if, but only

if, adequate notice is given to the opposing party

and that party fails to establish “that the evidence

is unreliable or lacking in probative value.” In any

event, no evidence is admissible the “probative

value of which is substantially outweighed …

by the danger of unfair prejudice.” Even in our

civilian criminal courts, hearsay is generally only

excluded if it does not meet any of a long list of

exceptions and if it is presented to a civilian jury.

Federal Rule of Evidence 1101 makes the rules

inapplicable to preliminary questions of fact, grand

jury proceedings and miscellaneous proceedings

such as sentencings, bail hearings, suppression

hearings and similar matters that are normally tried

before judges without a jury. In many instances, it

simply would be impractical or impossible to make

available to testify personally in protracted court

proceedings military or intelligence officers who are

in combat on the other side of the world.

Myth Number Three: The MCA is deficient in

that it does not provide for alien unlawful enemy

combatants to be tried by a jury of their peers.

Although different from the practice in U.S. civilian

courts, this is not unusual in the world at large. The

various international courts such as the International

Court for the Former Yugoslavia or the International

Court for Rwanda also use the commission system,

rather than attempt to locate a lay jury of the

defendant’s peers. Juries are not the norm in those

nations which follow the civil law system, which is

a large part of even the Western Democracies.

Myth Number Four: The military commissions

do not have an exclusionary rule to prevent the

introduction of otherwise reliable evidence “on the

grounds that the evidence was not seized pursuant

to a search warrant or other authorization.” True,

but the exclusionary rule is designed to deter police

misconduct. In the case of military commissions, the

evidence is often gathered by soldiers who cannot be

expected to be trained in evidence collection. Indeed,

U.S. courts are not even authorized to issue search

warrants for places outside of the United States. As

the Supreme Court has stated: “[T]he purpose of

the Fourth Amendment was to protect the people of

the United States against arbitrary action by their

own Government; it was never suggested that the

provision was intended to restrain the actions of

the Federal Government against aliens outside of

the United States territory.” Rather, the standard for

admissibility is this: “Evidence shall be admissible

if the military judge determines that the evidence

would have probative value to a reasonable person.”

This is wholly a truth-seeking standard, without

any trade-offs to serve other societal values such as

deterring police misconduct.

Myth Number Five: The MCA exempts its

proceedings from the speedy trial provisions of

the Uniform Code of Military Justice. True again,

but this, too, makes sense in context. Many of the

unlawful enemy combatants held by the military

were arrested in order to obtain intelligence, and

they are not detained as a result of the pendency of

proceedings before the military commissions. As

Justice O’Connor noted in the Hamdi case: “The

capture and detention of lawful combatants and the

capture, detention, and trial of unlawful combatants,

by ‘universal agreement and practice,’ are ‘important

incident[s] of war,” and the United States may detain

4

Homeland Security and the Rule of Law:

Methodology and Myth

such people – separate and apart from trials by

military commissions – “for the duration of the

relevant conflict.”

Myth Number Six: The MCA does not always require

a unanimous vote for conviction. Again true, but it

does require the commission to have at least twelve

members and that they be unanimous as to both guilt

and sentence before imposing a death penalty.

The use of secret military tribunals to try those

charged as unlawful combatants is a procedure first

approved by our Supreme Court in the 1942 Ex Parte

Quirin case involving World War II Nazi saboteurs.

Such tribunals must be available as an option where

sensitive intelligence information might be disclosed

in a trial in open court or where it is deemed wise

to avoid providing a public platform for terrorists to

spew their messages of hatred and extremism. Such

a tribunal might well be appropriate, for example,

for the trial of Osama bin Laden himself if and when

he is finally brought to justice.

Myth Number Seven: Is not a myth at all, but a

shocking reminder of a lingering deficiency in

our system of justice. There is, in fact, no crime

of terrorism triable in our federal criminal courts.

In 1996, Congress passed the Anti-terrorism and

Effective Death Penalty Act – commonly known as

the AEDPA – which added Section 2332b to Title 18,

the Federal criminal code. Subsection (g)(5) states

that “the term ‘Federal crime of terrorism’ means an

offense that … is calculated to influence or affect the

conduct of government by intimidation or coercion,

or to retaliate against government conduct; and …”

is a violation of any one of a list of offenses that

includes such things as destroying aircraft, taking

hostages, and using a weapon of mass destruction.

Presumably, these particular offenses were listed

because Congress believed them to be the sort of

things that terrorists do.

But, what some academics call the “dirty little

secret of Section 2332b” is that Congress did not

impose any penalty for committing such a defined

“federal crime of terrorism.” Nowhere. What the

section actually prohibits is conduct that transcends

national boundaries and is a violation of one of a

wholly separate and substantially shorter list of

offenses contained in subsection (a). Nowhere

in the entire 106 pages of the AEDPA is the term

“federal crime of terrorism” used except in its own

definition! Apparently, having trouble agreeing on a

definition of terrorism, Committee members drafting

the bill adopted the concept of “transcending

national boundaries” as a surrogate for a definition

of terrorism. They altered the “prohibited acts”

portion of the statute so that it referred to “conduct

transcending national boundaries” instead of to a

“federal crime of terrorism,” but no one thought

to remove the now orphaned definition from

the statute.

The only actually crime of “terrorism” as such is

set forth in the Military Commissions Act. Section

950v(b)(24) of the MCA creates an offense named

simply “Terrorism,” which prohibits an unlawful

combatant from intentionally killing or inflicting

great bodily harm upon protected persons if they

do so in a manner calculated to influence or affect

the conduct of a government or civilian population

by intimidation or coercion or to retaliate against

government conduct.

There are at least 14 other definitions of “terrorism”

in the United States Code. Sometimes the law defines

it by the purpose for which an act is committed, such

as to coerce a government. Sometimes Congress

defines it by simply providing a list of offenses that

are deemed to be terrorism-related. And, sometimes

the definition combines both the purpose and a list of

offenses. Still other offenses are generally deemed to

be terrorism because of the conduct involved – such

as using a biological weapon – without any specific

mention of the word “terrorism.” A fifth definitional

approach employs a surrogate concept, such as the

above-noted “transcending national boundaries.”

One statute, Title 18, Section 2332, although in

a chapter entitled “Terrorism” does not use that

word at all, but attempts to limit its otherwise very

broad scope by providing that “No prosecution

for any offense described in this section shall be

undertaken by the United States except on written

certification of the Attorney General or the highest

ranking subordinate of the Attorney General with

responsibility for criminal prosecutions that, in the

judgment of the certifying official, such offense was

intended to coerce, intimidate, or retaliate against a

government or a civilian population.” Apparently,

5

Homeland Security and the Rule of Law:

Methodology and Myth

Congress decided it was better to assign the

determination of whether an act constitutes terrorism

to the Attorney General rather than to a judge

and jury.

To be sure, Congress is not alone in finding it

difficult to define “terrorism.” There is no agreed

definition under international law or in academia,

either. Much academic literature defines terrorism

as the unlawful targeting of non-combatants, a

concept generally absent from legal definitions.

And, of course, the parameters of a definition may

vary by the use to which the term is put. Still, the

many, varied, and inconsistent definitions in the

United States Code reflect the lack of a unified legal

theory for identifying just what conduct should

be prohibited.

The AEDPA is itself an example of this reactive

approach. The statute was largely a result of

recommendations from the Department of Justice

based upon its experiences in trying those who

bombed the World Trade Center in 1993 and in

related cases involving al Qaeda members in New

York. The Department found the best available

statute in the early 1990s to be the 19th Century

prohibition on seditious conspiracy. That was the

charge used because at the time the Code lacked

suitable offenses for intervening in a terrorist

scheme before the terrorists actually struck. The

AEDPA added the offenses of providing material

support for terrorism in order that the criminal law

might be brought to bear to deprive terrorists the

resources needed to carry out attacks. We should

remember that the notion of prevention, rather than

prosecution, is properly given priority in the field

of terrorism. As noted, public expectations may

be disappointed in some cases where terrorist acts

are thwarted by effective intelligence gathering

that did not produce legally admissible evidence

that would support a criminal prosecution or when

prosecution is deemed to be unwise because of the

potential exposure of informants or sophisticated

intelligence gathering techniques. The public and

the media must understand that not all bad guys

will be prosecuted, and many of those who are will

be charged with offenses less dramatic than actual

bombings or killings.

III.

The AEDPA is hardly the only example of Congress

taking a somewhat addled approach to defining

criminal offenses. Our federal criminal law has

developed largely as a series of sporadic responses

to widely publicized criminal conduct that either

touched upon a federal interest or provoked an

expression of congressional outrage. It has been

cast in a multitude of fashions that reflects the

idiosyncratic imprint of a two century-long parade

of draftsmen possessing quite different views of

crime, justice, and the English language, but that is

a story for another day.

Suffice to say that while Congress may not have

identified what constitutes the offense of “terrorism,”

it has found time to create over 4,450 separate

crimes, including such supposedly nefarious federal

offenses as:

• using a motor vehicle to capture a wild burro on

public land;

• reproducing the image of “Smokey Bear” without

authorization;

• wearing the uniform of a postman in a theatrical

production that tends to discredit the postal

service;

• taking artificial teeth into a state without approval

of a local dentist;

• using a personal check to pay a debt of less than

one dollar; and

• broadcasting information concerning prizes in a

fishing contest conducted for profit.

It has long been clear that we need a body of law

that is reasonably accessible, permitting both

lawyers and laymen, if so disposed, to locate its core

provisions with the expenditure of only a modest

amount of effort. But that effort has languished

without progress over nearly two centuries.

6

Homeland Security and the Rule of Law:

Methodology and Myth

***

We must recognize that some of the actions taken

since 9/11 are controversial. That controversy will

continue. We must work to make sure that the

debate and the dissenters are correctly informed

about just what the various legal reforms do and

do not do. The law will continue to evolve as law

enforcement focuses on a prevention paradigm and

as, one continues to hope, the federal criminal law is

someday truly codified in a rational manner.

When all is said and done, I am confident that

ways will be found to reconcile our liberties with

our national security. The key will be in our longestablished reliance on the principles of democracy

and the rule of law. An observer once noted that

the beauty of our system is not that it is always

right, but that it is usually responsive. And so it is

and, I expect, will continue to be. I am banking on

this principle to help guarantee that we not only

survive the present challenges, but continue to stand

as an exemplar for all those countries which seek

the blessings of liberty and justice and security for

their people.

K&L Gates comprises multiple affiliated partnerships: a limited liability partnership with the full name K&L Gates LLP qualified in Delaware and

maintaining offices throughout the U.S., in Berlin, in Beijing (K&L Gates LLP Beijing Representative Office), and in Shanghai (K&L Gates LLP

Shanghai Representative Office); a limited liability partnership (also named K&L Gates LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining our London

and Paris offices; a Taiwan general partnership (K&L Gates) which practices from our Taipei office; and a Hong Kong general partnership (K&L

Gates, Solicitors) which practices from our Hong Kong office. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations in the jurisdictions in which its offices

are located. A list of the partners in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office.

This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used

or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer.

Data Protection Act 1998—We may contact you from time to time with information on K&L Gates LLP seminars and with our regular newsletters,

which may be of interest to you. We will not provide your details to any third parties. Please e-mail london@klgates.com if you would prefer not

to receive this information.

©1996-2008 K&L Gates LLP. All Rights Reserved.

7