Appellate, Constitutional & Governmental Litigation Alert Extraterritorial Reach of U.S. Laws After

advertisement

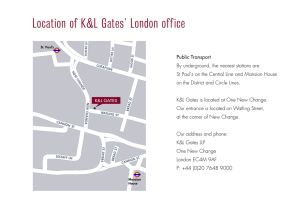

Appellate, Constitutional & Governmental Litigation Alert July 1, 2010 Authors: John P. Krill, Jr. john.krill@klgates.com +1717.231.4504 Amy O. Garrigues amy.garrigues@klgates.com +1.949.466.1275 K&L Gates includes lawyers practicing out of 36 offices located in North America, Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and represents numerous GLOBAL 500, FORTUNE 100, and FTSE 100 corporations, in addition to growth and middle market companies, entrepreneurs, capital market participants and public sector entities. For more information, visit www.klgates.com. Extraterritorial Reach of U.S. Laws After Morrison v. National Australia Bank The United States Supreme Court has held that key anti-fraud provisions of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (“Exchange Act”) and regulations promulgated under it do not apply outside the borders of the country. While this decision immediately affects securities litigation, it seems likely also to have an impact in other areas of law, to the extent it revitalizes the presumption against extraterritorial application of laws enacted by Congress. Morrison et al. v. National Australia Bank involves a complaint filed in U.S. District Court in New York by three Australians who had bought shares of stock in National Australia Bank (“National”) that were traded on the Australian Stock Exchange, but not on any American exchange. Their suit alleged that National deceived them by overstating the value of an American subsidiary, a mortgage servicer. The shareholders sued National, its American subsidiary and their officers. In its June 24, 2010, decision in Morrison, the Court held that Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act does not apply outside the United States. Section 10(b) makes it unlawful, “in connection with the purchase or sale of any security,” to use “any means of interstate commerce or … any national securities exchange” for the purpose of promoting “any manipulative or deceptive device or contrivance” that is contrary to the regulations of the Securities and Exchange Commission. Even though the plaintiffs alleged deceptive conduct within the United States, the Court held that the law, which applied “in connection with the purchase or sale of any security,” did not extend to transactions on a foreign stock exchange.1 Activities allegedly related to the deception that took place in the United States were insufficient to bring the conduct within the scope of the statute. Because Section 10(b) does not state that it applies outside the U.S., the Court held that the presumption against extraterritorial application controlled. The opinion of the Court, authored by Justice Scalia, recites a history of how the Courts of Appeals cut back and ultimately discarded the presumption in 10(b) cases. For example, in Schoenbaum v. Firstbrook,2 the Second Circuit said that “neither the usual presumption against extraterritorial application of legislation nor the specific language . . . show Congressional intent to preclude application of the Exchange Act to transactions regarding stocks . . . which are effected outside the United States.”3 In Schoenbaum, the Second Circuit effectively reversed the presumption by requiring that there be evidence of legislative intent to restrict the territorial reach of a law. 1 Another plaintiff, Morrison, was an American who bought American Depositary Receipts (“ADRs”) for shares of National. The ADRs were traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Morrison’s claims were dismissed by the District Court and he did not appeal. The Supreme Court therefore did not decide whether Section 10(b) would cover his claims. 2 405 F.2d 200 (2d Cir. 1968). 3 Shoenbaum, 405 F.2d at 206. Appellate, Constitutional & Governmental Litigation Alert The Supreme Court also criticized Leasco Data Processing Equipment Corp. v. Maxwell,4 where the Second Circuit said, in effect, that the presumption only applies when Congress would not have “prescriptive jurisdiction,” i.e. lawmaking authority, over conduct within the United States. Leasco, in other words, said that when Congress has no authority within the United States, it cannot be presumed to have it outside the country.5 Schoenbaum and Leasco essentially abrogated the presumption against extraterritorial effect of laws that are valid within the country. The Supreme Court reinstated the presumption by simply noting that the statute in question did not express the intent of Congress for it to have extraterritorial effect. Morrison may signal a return to basic principles of jurisprudence in the territorial application of U.S. law. If so, securities law is not the only area that may be affected. In federal environmental laws there are questions of extraterritorial effect. For example, in Pakootas v. Teck Cominco Metals, Ltd.,6 the Ninth Circuit gave extraterritorial application to the federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (“CERCLA”). Pakootas held that a Canadian smelter could be held liable to U.S. plaintiffs for the discharge of waste into a river that flows across the border. The Ninth Circuit in Pakootas applied CERCLA to a foreign entity, based on the domestic effects of the waste on U.S. soil without using the presumption against extraterritoriality. CERCLA, like Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act, does not identify its territorial limits.7 Similarly, courts have found the National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”) to apply extraterritorially, although NEPA does not explicitly grant extraterritorial jurisdiction. For example, in Environmental Defense Fund v. Massey,8 the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia held that NEPA’s Environmental Impact Statement 4 468 F.2d 1326 (2d Cir. 1972). Id. at 1333-1334. 6 452 F.3d 1066 (9th Cir. 2006). 7 Id. at 1077-1079. 8 986 F.2d 528 (D.C. Cir. 1993). 5 requirement applied to the waste incineration plan of a U.S. base in Antarctica even though the environmental impact would not affect the American environment, or that of any other sovereign.9 The questions of extraterritorial effect also extend to health care laws. For example, Section 111 of the Medicare and Medicaid SCHIP Extension Act of 2007 imposes reporting requirements on insurers that make payments to Medicare beneficiaries for medical treatment of personal injuries or that have the effect of releasing such medical claims. The statute does not state any territorial limits on where the insurer is located or where the treatment or payment occurs. The United States Department of Health and Human Services, through its Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”), has indicated that it considers the reporting requirement to apply to foreign insurers. CMS expects both domestic and foreign insurers to register and to commence reporting in the near future. In light of Morrison, perhaps the government will reevaluate its position. Morrison does not say that Congress cannot make a law applicable to conduct outside the United States. If a statute expressly extends its reach outside the country, the presumption against extraterritoriality does not apply. In such instances, there will still be a question of whether Congress has the legislative jurisdiction to regulate foreign conduct, but that would be decided under other principles of jurisprudence. Morrison’s reassertion of the presumption against extraterritoriality will be well received by many who seek to promote international commerce. The amici in support of the successful respondent included both private trade organizations and governments, such as France and the United Kingdom. Morrison is a step in the direction of the International Chamber of Commerce’s 2006 policy statement, calling upon courts, as well as legislatures, to recognize the negative impact on world trade that the extraterritorial application of national laws can have. 9 Id. at 536-537. July 1, 2010 2 Appellate, Constitutional & Governmental Litigation Alert Anchorage Austin Beijing Berlin Boston Charlotte Chicago Dallas Dubai Fort Worth Frankfurt Harrisburg Hong Kong London Los Angeles Miami Moscow Newark New York Orange County Palo Alto Paris Pittsburgh Portland Raleigh Research Triangle Park San Diego San Francisco Seattle Shanghai Singapore Spokane/Coeur d’Alene Taipei Tokyo Warsaw Washington, D.C. K&L Gates includes lawyers practicing out of 36 offices located in North America, Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and represents numerous GLOBAL 500, FORTUNE 100, and FTSE 100 corporations, in addition to growth and middle market companies, entrepreneurs, capital market participants and public sector entities. For more information, visit www.klgates.com. K&L Gates is comprised of multiple affiliated entities: a limited liability partnership with the full name K&L Gates LLP qualified in Delaware and maintaining offices throughout the United States, in Berlin and Frankfurt, Germany, in Beijing (K&L Gates LLP Beijing Representative Office), in Dubai, U.A.E., in Shanghai (K&L Gates LLP Shanghai Representative Office), in Tokyo, and in Singapore; a limited liability partnership (also named K&L Gates LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining offices in London and Paris; a Taiwan general partnership (K&L Gates) maintaining an office in Taipei; a Hong Kong general partnership (K&L Gates, Solicitors) maintaining an office in Hong Kong; a Polish limited partnership (K&L Gates Jamka sp. k.) maintaining an office in Warsaw; and a Delaware limited liability company (K&L Gates Holdings, LLC) maintaining an office in Moscow. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations in the jurisdictions in which its offices are located. A list of the partners or members in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office. This publication is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. ©2010 K&L Gates LLP. All Rights Reserved. July 1, 2010 3