2409.26c,40 Page 1 of 10 FOREST SERVICE HANDBOOK

advertisement

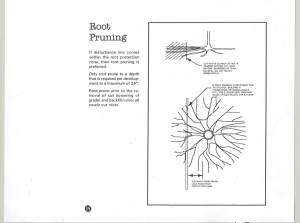

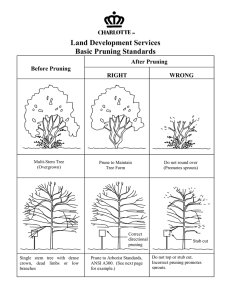

2409.26c,40 Page 1 of 10 FOREST SERVICE HANDBOOK PORTLAND, OREGON 2409.26c - TIMBER STAND IMPROVEMENT HANDBOOK R-6 Amendment No. 2409.26c-93-2 Effective May 13, 1993 POSTING NOTICE. Amendments to this handbook are numbered consecutively. Check the last transmittal sheet received for this handbook to see that the above amendment number is in sequence. If not, obtain intervening amendment(s) at once from the Information Center. Do not post this supplement until the missing one(s) is received and posted. After posting, place the transmittal at the front of the title and retain until the first transmittal of the next calendar year is received. The last Amendment to this handbook was 2409.26c-93-1 (!2409.26c Contents). Document Name Superseded New (Number of Sheets) 2409.26c,40 Digest: Chapter 40 - New Chapter, updates pruning for wood quality processes. JOHN E. LOWE Regional Forester 10 R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 2 of 10 FSH 2409.26c - TIMBER STAND IMPROVEMENT HANDBOOK R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-2 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 CHAPTER 40 - PRUNING 41 INTRODUCTION 41. 1Objectives of Pruning 42 PRETREATMENT EVALUATION 42. 42.2 1Acceptable Stand Types and Management Areas Analysis of Potential Gain in Clear Wood Volume and Increased Value 43 PROJECT PLANNING 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.31 43.32 43.33 43.4 Environmental Analysis Silvicultural Prescription Interdisciplinary Coordination Fire Management Wildlife Pest Management Implementation of Project Plans 44 TREATMENT METHODS 44.1 44.2 44.3 Hand Saws Power Saws Powered Pruning Equipment 45 MONITORING 45.1 45.2 45.3 Objectives Operational Monitoring Post-Project Monitoring 46 RECORDS AND REPORTS 47 AVAILABLE RESOURCES R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 3 of 10 41 - INTRODUCTION. This chapter provides guidelines for the use of pruning as a timber stand improvement treatment. Identification of specific methods, techniques, and priorities is left to Forest supplementation. Pruning may be defined as removal of limbs on the lower portion of a tree. 41.1 - Objectives of Pruning. The primary objectives of pruning are to increase the clear wood volume of a tree when harvested, and disease control. Other objectives may include wildlife habitat improvement and aesthetics. 42 - PRETREATMENT EVALUATION. An analysis should be completed to determine the need for pruning, predict the expected financial return and outcome in increased clear wood volume, effective disease control, and so forth. The analysis should include the effect of pruning on nontimber values and assess possible beneficial and adverse impacts from the activity. An evaluation does not have to be done for all pruning projects but should be done when first considering a project, or when factors affecting the analysis significantly change. The following is the recommended process for evaluating a pruning project. 42.1 - Acceptable Stand Types and Management Areas. Pruning should be considered only in stand types where documented research indicates a positive return on investment, or where substantial resource benefits from disease control can be demonstrated, for example, control of dwarf mistletoe, white pine blister rust, and western gall rust. 1. Acceptable Species. Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine have had sufficient analysis on an operational and research basis to warrant investment within Region 6. Other species may be considered if a justification of a pruning investment can be made, such as pruning western white pine for blister rust control, or integrating pruning of trees for bough collection or other special forest products. Species which exhibit significant epicormic branching should not be considered for operational pruning. 2. Acceptable Management Areas. Forest Plans outline the management objectives for each management type within the Forest. The silvicultural regimes for these areas will determine the appropriateness of pruning. For example, management areas which would not allow the removal of pruned trees in sufficient number (that is, areas allowing salvage type operations only) or areas requiring long rotations well past financial maturity of a pruning investment may not be compatible with pruning. However, such constraints should not preclude the option of further analysis. Possibilities, such as removing pruned trees in a thinning within the long rotation areas, may be feasible. 42.2 - Analysis of Potential Gain in Clear Wood Volume and Increased Value. The following are recommended steps in determining the wood quality gain from pruning. Steps 1 through 3 identify assumptions which need to be addressed and step 4 identifies a method to analyze pruning operations which incorporate the latest research in pruning recovery. R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 4 of 10 1. Pruning Height. To determine the length of the bole to be pruned, the following factors should be considered: a. Projected log length standards at time of harvest. To help assure the highest value from the clear wood produced, pruning lengths should accommodate the most likely log lengths marketable at time of harvest. b. Relation of pruning costs with pruning height. Considering the available pruning tools, what are the incremental costs of increasing the pruning height? c. Number of pruning entries. If the final pruned log length is 20 feet, one alternative may be to prune once to approximately 10 feet (considering percent of live crown) when the stand is younger with a smaller diameter, then pruning the additional 10 feet at a later entry (pruning in two lifts). The other alternative would be to prune once to 20 feet at the older age. 2. Stand Entry Criteria. Consider the following factors when determining the optimum time in stand development to prune: a. Pruned log size and pruning's impact on tree growth. To produce the most clear wood at time of harvest, trees should be pruned at the youngest possible age without significantly affecting growth. This may be accomplished by pruning a tree to the desired height by removing dead limbs on the lower portion of the bole and live limbs on the lower live crown, which are not significantly contributing to stem growth. A review of Douglas-fir pruning trials conducted by O'Hara (1991) indicates it is likely one third of the live crown may be removed from a young Douglas-fir tree without significantly affecting growth. However, considering the one-third live crown removal without relating it to the trees pretreatment live crown ratio, may result in considerably different growth response due to the pruning. If using the onethird rule and assuming the desired pruning height was 18 feet, one option would be to prune when the tree has reached a height of 42 feet and the crown has receded 6 feet off the ground, leaving a 36-foot live crown. Pruning to 18 feet would cut 12 feet into the live crown, removing approximately one-third of the crown. Pruning later, assuming further crown recession, could remove only dead limbs and leave a larger knotty core. Another option, which will result in a pruning height of 18 feet with a small knotty core, is to prune in multiple lifts starting at the sapling stage. However, care must be taken in early pruning to avoid removing enough live crown to cause slowed growth which could affect crown position within the stand and growth potential before harvest. b. Pruned limb size. Pruning of limbs larger than 1 inch in diameter may increase cost due to cutting difficulty; increase the potential for rot because of the increased likelihood of heartwood; and take longer for the cut surface to heal. R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 5 of 10 c. Financial carrying cost of pruning in regard to the harvest age. Pruning a stand later than suggested above to maximize clear wood volume production may be preferred to reduce the length of time between pruning investment and harvest. However, this will increase the size of the knotty core and probably reduce the financial return. When possible, pruning for wood quality should be evaluated in conjunction with special forest products projects. This not only allows earlier pruning, but often times can be incorporated as a requirement of the contract, and be accomplished at no additional cost to the Government. d. Timing with other silvicultural activities. Pruning after a commercial or precommercial thinning may be preferred to assure only crop trees are pruned, but may cause pruning difficulty because of thinning slash. Pruning prior to commercial thinning will premark the stand for thinning, but pruned trees may be damaged during the harvest operation. Pruning without thinning may increase the potential for unpruned competitors to outgrow pruned trees. Also, existing studies indicate higher financial returns from pruning stands with quite low stocking. e. Timing with consideration of possible disease, insect, and wildlife impacts. Childs and Wright (1956) indicate pruning in the fall reduces the potential for incidence of fungal infections in Douglas-fir, compared with spring pruning, although in either case stem decay was insignificant. 3. Pruned trees per acre. Trees to be pruned should be capable of rapid enough growth to produce an acceptable amount of clear wood at time of harvest. Generally, the first priority for pruned tree selection is the larger, faster growing trees in the stand that have the potential of providing the most clear wood and greatest economic return. Prune tree selection may also be influenced by resource needs, such as improving or enhancing wildlife habitat. The target trees per acre to be pruned will depend on projected number of trees reaching final harvest and projected growth rates of trees distributed throughout the various crown classes. A small allowance for mortality may be necessary. 4. Project Value and Volume Gained from Pruning. Determining the value and volume gained from pruning requires a number of financial and lumber recovery assumptions. A list of publications found in subsection 47 contain some of the more applicable studies and analysis procedures for Region 6. The Douglas-fir "DF PRUNE Users Guide" (Fight, 1991) and ponderosa pine "PP PRUNE Users Guide" (Bolon, 1991) simulators are recommended for projecting the value of pruning Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine. The use of "Price Projections for Selected Grades of Douglas-fir, Coast hem-fir, Inland hem-fir, and ponderosa pine lumber (Haynes and Fight, 1992)" is recommended to estimate future lumber values needed in the above simulators. "Production, Prices, Employment and Trade in Northwest Forest Industries" (Res. Bull. Published quarterly) is recommended for current lumber prices and past trends. The following data are also required in order to use the simulators: R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 6 of 10 a. Pruning and harvest age. b. Diameter of potential pruned trees at time of pruning and harvest. c. Height of potential pruned trees at time of pruning and harvest. d. Limb diameter. (An estimation of the diameter of the largest limb on the pruned portion of the bole, at time of pruning and final harvest. This, along with the diameter breast height at age 20 is needed for the DF PRUNE simulator only.) e. Estimated pruning cost per tree. It should be noted that current log grading rules for Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine rely heavily on knots and knot indicators for determining grade and value. Due to the nature of tree growth, knot indicators will remain on the bark surface even though several inches of clear wood may exist below the indicator. 43 - PROJECT PLANNING. If the above analysis indicates pruning is a viable treatment, specific areas may be identified to implement a project. The above analysis procedure will help provide criteria for stand selection and pruning specifications. 43.1 - Environmental Analysis. An Environmental Analysis (EA) should be completed according to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). NEPA defines a process which provides for scoping and an interdisciplinary approach which helps insure all resources are adequately considered and concerned publics are involved. When an analysis and past experience indicate no significant effect will occur, a categorical exclusion may be considered. Public sensitivity and other local conditions may affect the choice of documentation required. 43.2 - Silvicultural Prescription. After an EA is prepared for a project, a silvicultural prescription should be written displaying the preferred alternative. The analysis and prescription shall include documentation for stand selection criteria and operational specifications. Stand selection criteria shall include; (1) stocking levels (lower stocked stands usually produce a greater return from pruning because pruned trees have more room to grow and produce more clear wood), (2) site index (higher sites will usually produce more clear wood volume per pruned tree), (3) height to live crown, and (4) timing with other silvicultural activities, both completed and planned. Operational specifications should include; (1) pruning height, (2) tree selection (specifications should designate the healthier, well formed trees, most likely to be dominants and codominants at harvest time as pruned trees), (3) allowable live crown removal or minimum live crown ratio following pruning, (4) allowable branch stub length, (5) restrictions on stem damage, and (6) desired pruning equipment. 43.3 - Interdisciplinary Coordination. R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 7 of 10 43.31 - Fire Management. Coordination with Fire Management is specified in WO AMEND FSM 2476.4. It is recommended that fuels treatment needs be evaluated on the basis of a risk analysis to determine the appropriate level of hazard reduction required. In planning pruning projects, emphasis should be placed on avoiding development of excessive hazards that would make adequate protection impractical. Size, location, distribution of pruning units, scheduling of pruning or slash disposal on nearby units, disposal plans, and protection facilities all have a bearing on what may be an excessive hazard. It is unlikely that fuels created from pruning alone would require treatment. 43.32 - Wildlife. Evaluate potential pruning impacts (positive and negative). For example, pruning may encourage big game damage to the cambium of young trees, and in areas with a history of this, pruning may not be advisable; or measures may need to be taken to minimize potential damage. 43.33 - Pest Management. Evaluate the possible insect and disease impacts which may occur in a pruned stand. Specifically, the potential effects of insects and diseases entering trees through wounds, or their attraction to pruned trees, should be addressed in the prescription. It should be noted at this time, there is no documented evidence that this is a problem for Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine. 43.4 - Implementation of Project Plans. The successful implementation of a pruning project should be evaluated on how well it met the objectives stated in the prescription. Pruning may be completed by contract or force account labor, but acceptable performance shall be of equal quality for both, as verified through inspection and project specification compliance. 44 - TREATMENT METHODS. 44.1 - Hand Saws. Cutting limbs with hand saws is the most common method of pruning in the Region. At present, it appears to be the most cost-effective method of pruning trees to a height of 18-20 feet. A number of pruning saws are available with extension poles. 44.2 - Power Saws. Chain saws are an effective method which could be used on the lower portion of the bole, but care must be taken to prevent damage to the tree. If considering the use of chain saws because of large limb size, reevaluate the treatment priority of the age and size of trees to be pruned. Pole mounted power saws and clippers are also available on the market, but have not found widespread use in Forest pruning operations. 44.3 - Powered Pruning Equipment. A number of robot-type pruners have been developed which self-propel up a tree while removing limbs. At present, they seem to be in the developmental stage with little use at the operational level in the United States. 45 - MONITORING. Monitoring is the systematic observation, measurement, collection, recording, and evaluation of data to determine the effects of treatment. R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 8 of 10 The monitoring plan developed at the time the prescription is prepared includes general and specific items to be monitored and the time when the appropriate monitoring is to be accomplished. 45.1 - Objectives. The success of the prescription implementation should be demonstrated by the results of an effective monitoring program. Monitoring also provides information to determine if retreatment is needed, and if results are outside of prescription tolerances. 45.2 - Operational Monitoring. Operational monitoring includes project implementation and achievement of the short-term objectives of the prescription. This phase of monitoring includes compliance with pruning specifications and determining the degree to which resource objectives have been met. It primarily occurs during, and immediately after, the actual pruning operation. 45.3 - Post-Project Monitoring. Post-project monitoring will determine whether or not the stand is developing as projected and whether the long-term objectives of the prescription are being met. Post-project monitoring should address such items as: 1. Stand development. Are the pruned trees gaining as much clear wood as predicted, and more importantly, are they maintaining dominance over unpruned trees? 2. Problems with heal-over of cut limbs. In pruning for wood quality or disease control, operational and post-project monitoring will help provide information to assist in developing future prescriptions for similar stands; provides information for updating of Forest and resource plans through better definition of stand growth models; provides an opportunity to more accurately predict the timing of future stand entries; and allows rescheduling when necessary. It is not feasible or necessary to conduct a thorough long-term monitoring of all pruned stands. Sampling of different stands and treatment prescriptions provides a more efficient method for evaluating performance. The use of benchmark prescriptions is the recommended method for sampling a variety of recurring stand conditions. Information gathered through monitoring shall be recorded and maintained for future use. 46 - RECORDS AND REPORTS. As pruning needs are identified, enter the acreages in the SILVA portion of the automated Timber Activity Control System (TRACS) by productivity class, state, Forest, and Ranger District. These data are essential for displaying funding needs to Congress. R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 9 of 10 Maintaining accurate records is extremely important. The location of pruned stands, volume of clear wood and accompanying value can be accurately estimated if reliable records exist. Although destructive sampling of representative trees near harvest time can determine the amount of clear wood, it would be more efficient to combine this method with accurate records to provide the best data at harvest time. As a minimum, records for pruned stands should include the number of pruned trees per acre, average diameter of pruned trees at time of pruning, pruning height, and the criteria for tree selection. Records should also include accurate maps of pruned stand locations. Reporting is a requirement and shall be timely and accurate. FSM 2496 contains instructions for National reporting requirements. Refer to the Region 6 Guide to Silvicultural Reporting for specific information on reporting attainment and certification of timber stand improvement activities. 47 - AVAILABLE RESOURCES. Forests and Districts are encouraged to exchange information, ideas, and methods for improving pruning practices. A large body of literature exists on the subject of pruning, and has been incorporated into a bibliography (O'Hara, 1989) containing over 1,100 references. This publication and other selected publications are listed below: Barrett, J.W. 1968. Pruning of Ponderosa Pine...effect on growth. USDA Forest Service. Research Paper. PNW-68. 9 p. Bolon, N. ,R.D. Fight and J.M. Cahill. 1992. PP PRUNE Users Guide. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-289. Cahill, James M. 1991. Lumber recovery from pruned young-growth ponderosa pine. Forest Products Journal. Cahill, J.M., T.A. Snellgrove and T.D. Fahey. 1988. Lumber and veneer recovery from pruned Douglas-fir. Forest Products Journal 38(9):27-32. Childs, T.W. and E. Wright. 1956. Pruning and occurrence of heart rot in young Douglas-fir. USDA Forest Service. Pacific Northwest Research Station. Research Note No. 132. 5 p. Fight, R.D., J.M. Cahill, and T.D. Fahey. 1992. DF PRUNE Users Guide (Revision of PRUNESIM). USDA Forest Service. Pacific Northwest Research Station. General Technical Report. PNW-GTR-300. 12 p. Fight, R.D., J.M. Cahill, T.D. Fahey, and T.A. Snellgrove. 1988. A new look at pruning coast Douglas-fir. Western Journal of Applied Forestry. 3(2)46-48. R-6 AMENDMENT 2409.26c-93-1 EFFECTIVE 5/13/93 2409.26c,40 Page 10 of 10 Haynes, R.W. and R.D. Fight. 1992. Price Projections for Selected Grades of Douglas-fir, Coast hem-fir, inland hem-fir, and ponderosa pine lumber. USDA Forest Service. Pacific Northwest Research Station. Research Paper PNW-RP-447. Maguire, D.A., J.A. Kershaw, and D.A. Hann. 1991. Predicting effects of silvicultural regime on branch size and crown wood core in Douglas-fir. (accepted by Forest Science). O'Hara, K.L. 1989. Forest Pruning Bibliography. University of Washington, Stand Management Cooperative/Institute of Forest Resources Contribution No. 67. 74 p. O'Hara. K. L. 1991. A Biological Justification for Pruning in Coastal Douglas-Fir Stands. Western Journal of Applied Forestry. 5p. Shaw, E.W. and G.R. Staebler. 1950. Financial aspects of pruning. USDA Forest Service. Pacific Northwest Research Station. 45p. Staebler,G. R. 1963. Growth along the stems of full crowned Douglas-fir trees after pruning to specified heights. Journal of Forestry. 61(2):124-127. Stein, W.I. 1955. Pruning to different heights in young Douglas-fir. Journal of Forestry. 53:352-355. Warren, Debra D. Published quarterly. Production, prices, employment, and trade in Northwest forest industries. Research Bulletin. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.