Document 13805396

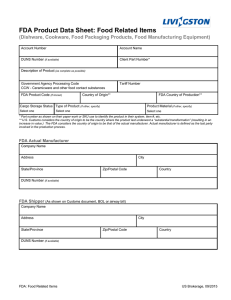

advertisement