Scope Inversion * Abstract

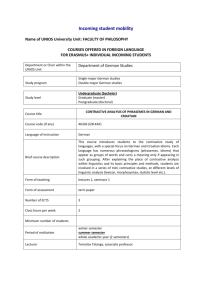

advertisement