Does English Need its Pronouns? Ezra Van Everbroeck

advertisement

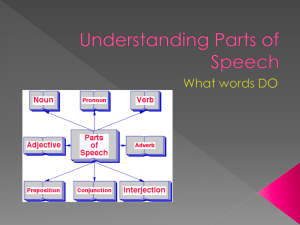

Does English Need its Pronouns? Simulating the Effect of Pro-drop on SVO Languages Ezra Van Everbroeck Maria Polinsky UC San Diego Linguistics 0108 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, CA 92093 ezra@ucsd.edu UC San Diego Linguistics 0108 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, CA 92093 mpolinsky@ucsd.edu Abstract We present the results from a large set of connectionist simulations exploring the effect of subject omission (prodrop) on languages with an SVO word order. We show that pro-drop only affects the learnability of the languages if there are no cues available to tell nouns and verbs apart. We also argue that neither creoles nor Mandarin Chinese instantiate the language type which was unlearnable in the simulations. Introduction It is well documented that many of the world’s languages allow sentential subjects to remain unexpressed (i.e. prodrop; Gilligan 1987): e.g. in Spanish, A comido la sopa ‘(S/He) has eaten the soup’ is a perfectly fine sentence even though it lacks an overt subject. Linguists have been studying this phenomenon for several decades, but it is still unclear to what extent pro-drop is correlated with other linguistic properties. While it was originally assumed that languages could only exhibit pro-drop if they also featured rich subject-verb agreement — like Italian and Spanish, where the agreement affixes on the verb essentially replace the information which is lost by omitting the subject (Jaeggli and Safir 1989) — it was soon pointed out that some languages which lack agreement systems altogether, like Mandarin Chinese and Thai, also exhibit frequent pro-drop (Huang 1984, 1989). To gain insight into the interactions between pro-drop and other linguistic parameters, we have run 12,000 neural network simulations to systematically investigate how languages with different basic word orders and varying degrees of overt morphological marking are affected by the introduction of pro-drop. By using computational models and artificial languages, we can control each parameter separately and also look at combinations of properties (i.e. types of languages) which are unattested in the real world — neither of which would be possible if we limited ourselves to more traditional, grammar-based typological research. In order to keep the results and discussion sections manageable, we will restrict ourselves here to the network models which had to learn languages with a basic Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) Garrison W. Cottrell UC San Diego Computer Science & Engineering 0114 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, CA 92093 gary@ucsd.edu word order. Cross-linguistically, the SOV word order is more frequent (Tomlin 1986; Dryer 1989), but SVO languages are more interesting for our purposes because they display more morphological variation than SOV languages (Siewierska 1996, 1998) and because a number of well-studied languages like English, Spanish and Mandarin Chinese are SVO. Experiment The use of neural networks for typological studies is a recent development in cognitive science, but there have already been several successful models (Christiansen and Devlin 1997; Lupyan and Christiansen 2002; Van Everbroeck 1999, 2003). For our simulations, we created simple context-free grammars capable of generating many different artificial languages, each of which represented a specific language type. The lexicon used to generate the training corpora consisted of 300 nouns (half animate, half inanimate), 100 verbs (half transitive, half intransitive) as well as several pronouns and morphological markers. The test lexicon contained new nouns and verbs but the same pronouns and markers. For each language type, the grammars were used to generate training and test corpora of 3,000 simple sentences. The possible sentences were SV and SVO, as well as V and VO for the language types in which subjects could remain unexpressed. In addition to word order and the presence/absence of pro-drop, the two other crucial parameters were the presence/absence of Subject/Object case-marking on the nouns, and the presence/absence of head-marking on the verbs. The latter could take the form of simple Tense/Aspect/Modality markers which essentially only help identify the verbs (Bybee 1985), valency markers indicating the number of arguments in the clause (e.g. McWhorter 1998), or rich subject-verb agreement. The architecture of the model used in our simulations consisted of a simple recurrent network (Elman 1990) augmented with a recurrent layer for the output units (see Figure 1). The latter functioned as a short-term memory and led to much faster training. At the input layer, the networks SVO Head-marking No prodrop [-case] [+case] None T/A/M Valency Agreement 96.2% 97.0% 96.8% 97.4% 96.8% 97.1% 96.5% 96.8% 45.8% 92.8% 95.8% 96.4% 96.1% 96.3% 92.6% 93.2% pro-drop Figure 1. Model architecture: Activation flows from the input layer at the bottom to three banks of output units (S, V, O). were shown one word of a sentence at a time. At the end of each sentence, a special ‘period’ pattern was presented to signal to the network that a new sentence was about to start. At the output layer, the networks were trained to build a representation of the entire sentence: there were separate banks of units for the subject, object and verb of the sentence and each bank had to be filled with the appropriate word from the sentence, or left empty if the sentence didn’t contain the element — e.g. the object bank was to remain empty in all intransitive sentences. The networks were trained using back-propagation for 10 epochs, and then tested on the sentences from the appropriate test corpus. The main error measure was the percentage of sentences for which the network got all three output banks correct; i.e. the pattern of activation over each bank of output units had to be closer to the correct word than to any other one. Results An ANOVA test reveals the importance of each linguistic parameter used for generating the artificial languages: prodrop, case-marking on the nouns, and head-markers on the verbs are all statistically significant (see Table 1). Effect SS Case 3177. 1 3177. 34.31 .000* Head 104E2 3 3460. 37.37 .000* 5403. 1 5403. 58.35 .000* Pro DF MS F p Table 1. ANOVA analysis results. If we look at individual language types and how well the trained networks were able to generalize to the new sentences in the test corpora, we find that test performance was excellent (> 90%) for all but one combination of linguistic features (see Table 2; the percentages in each cell are averages over 20 networks with different initial weights). The problematic language type combines an SVO word order with pro-drop, no case-marking on the nouns and no marking on the verbs. [-case] [+case] Table 2. Percentages of novel sentences of each language type which are parsed correctly. An analysis of the errors made by the various networks shows that telling the nouns apart from the verbs is the main problem caused by pro-drop. When all subjects are expressed, SVO languages are easy to parse because the first word is always the subject, the second word always the verb, and the third (if present) the object. (Note that these networks still make some mistakes because they are being forced to analyze sentences with nouns and verbs which they have never been trained on.) When there is pro-drop, however, this simple parsing strategy no longer works because the first word can be either the subject (in SV, SVO) or the verb (in V, VO); similarly, the second word can be either the verb or the object. Because the nouns and verbs are novel in the test corpora, some additional information is needed to identify which is which. The results in Table 2 demonstrate that marking the nouns (through case-marking) is as successful for the disambiguation task as marking the verbs (through any of its three types of marking). Interestingly, marking both simultaneously has very limited benefit. But if no marking is available to tell the nouns from the verbs, the networks fail to generalize to the novel sentences in the test corpus. Discussion A comparison of the network results in Table 2 with typological data on SVO languages suggests that some possible language types may be unattested (see Table 3). These ‘gaps’ in the space of possible languages could well be due to random historical events (Diamond 1997). On the other hand, the potential absence of natural languages which correspond to the type the networks found problematic suggests that some gaps could be motivated by cognitive factors such as learnability. There are two groups of natural languages which may correspond to the supposedly unattested type in Table 3. The first group consists of creole languages, i.e. languages which developed over the last 400 years or so in contact situations where speakers from mutually unintelligible languages were forced to communicate (Bickerton 1981; Thomason and Kaufman 1988; McWhorter 1998). SVO Head-marking No prodrop None T/A/M Valency Agreement [-case] [+case] English Russian ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? (45.8%) Hebrew Spanish Polish ?? Pasamaqoddy ?? prodrop [-case] [+case] ?? Table 3. Natural languages which correspond to the ones learned by the networks. All creoles share several linguistic properties, including an SVO word order and very little morphological marking on nouns and verbs. Many also derive partially from Spanish and Portuguese, both of which have frequent pro-drop. Nonetheless, if we look at the pro-drop phenomena observed in most creole languages, we find that they hardly ever go beyond the kinds of constructions which are also possible in English, a prominent non-pro-drop language. For example, it is possible to say the creole equivalent of ‘Seems like a good idea’ in Spanish-based Capeverdean Creole (Baptista 1995), Portuguese-based Papiamento (Kouwenberg 1990) and French-based Haitian Creole (DeGraff 1993). But the equivalent of Spanish Está comiendo la sopa ‘(S/He) is eating the soup’ is not acceptable, even in the creoles which derive from Spanish (Muysken and Law 1991). Moreover, in the few cases where creoles do allow pro-drop, they have also developed subject-verb agreement — e.g. Bislama (Meyerhoff 2000) and São Tomé Creole (Gilligan 1987). So, there is no evidence that creoles represent the language type which the networks have problems learning. The second group of potential counter-examples can be found among the languages of South-East Asia, including Thai, Lao, Vietnamese, and the varieties of Chinese. Although not all of them are historically related, they share a large number of linguistic features, including an SVO word order and minimal noun and verb morphology, due to their pro-longed geographical proximity (Cooke 1968; Bisang 1996). Crucially, some of these languages also exhibit very frequent pro-drop. In Thai, for example, unexpressed subjects occurred in about every second sentence in a large corpus (Aroonmanakun 1999). Similar numbers are often mentioned for Mandarin Chinese (Huang 1984, 1989; Tao 1996; Tardif, Shatz, and Naigles 1997). We limit ourselves to a discussion of Mandarin here because it is the best documented of these languages. A closer analysis of Mandarin shows that there are a number of discourse and structural constraints on the usage of pro-drop. In general, pro-drop is only allowed when the unexpressed element can be readily recovered from the discourse or the situational context (Huang 1995). The structural constraints involve co-verbs and pivotal nouns in serial verb constructions (Li and Thompson 1981); in both cases, they prevent pro-drop from causing a verb to appear where a noun would normally be expected. In addition, Mandarin actually has some clues which help identify verbs (e.g. aspect markers, auxiliaries and co-verbs — Li, Bates, and MacWhinney 1993) and nouns (e.g. numerals, classifiers, prepositions, and the ba and bei particles — Chang 1992). Finally, there is considerable evidence from acquisition studies that children learning Mandarin Chinese prefer a fixed SVO word order, both in perception and production, and also don’t make mistakes in using nouns as verbs or vice versa (Erbaugh 1983, 1986; Miao and Zhu 1992). The combination of all these factors suggests to us that Mandarin, although it may come closer than most SVO languages, is not an instantiation either of the type which the models could not learn. Conclusion Our connectionist simulations of the effect of pro-drop on SVO languages show that the presence of unexpressed arguments need not create serious problems for a language learner, at least if some morphological marking is available to distinguish the nouns in the language from the verbs. If no such source of information is available, the networks fail to generalize to sentences containing novel words. This finding meshes well with what is known about human language processing because people, and especially young children, do poorly when faced with structural ambiguities (Trueswell et al. 1999; Hawkins 2002). From a typological perspective, our results are relevant because they help determine which SVO language types are unattested for cognitive reasons as opposed to the result of historical accident. The fact that no real languages appears to instantiate the type which the networks found unlearnable, even when they could have been expected to do so as in the case of Spanish-based creoles, is a strong indication for us that computer simulations can make a valuable contribution to linguistic typology. On the other hand, we also want to stress that language simulations like ours currently have limited explanatory value because they do not include semantic or pragmatic information. Adding lexical semantics of the type described by Li, Burgess, and Lund (2000) is definitely possible, however, so this deficiency can presumably be addressed. Other future work includes the analysis of the verb-final (mostly SOV) and verb-initial (VSO, VOS) language types, as well as closer look at Riau Indonesian and Singapore English, two SVO languages about which controversial claims have been made with respect to their linguistic features (Gil 1994, 2003). References Aroonmanakun, Wiroote (1999). Extending focusing for zero pronoun resolution in Thai. Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University Baptista, Marlyse (1995). On the nature of Pro-drop in Capeverdean Creole. Harvard Working Papers in Linguistics 5: 3-17 Bickerton, Derek (1981). Roots of Language. Ann Harbor: Karoma Bisang, Walter (1996). Areal typology and grammaticalization: processes of grammaticalization based on nouns and verbs in East and Mainland South East Asian languages. Studies in Language 20.3: 519-597 Bybee, Joan L. (1985). Morphology. A Study of the Relation between Meaning and Form. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Chang, Hsing-Wu (1992). The acquisition of Chinese syntax. In HsuanChih Chen & Ovid J.L. Tzeng (eds.), Language Processing in Chinese, 277-311. Amsterdam: North-Holland Christiansen, Morten H. and Joseph Devlin (1997). Recursive Inconsistencies Are Hard to Learn: A Connectionist Perspective on Universal Word Order Correlations. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual Cognitive Science Society Conference, 113-118. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Cooke, Joseph R. (1968). Pronominal reference in Thai, Burmese, and Vietnamese. Berkeley: University of California Press DeGraff, Michel Frederic (1993). Is Haitian Creole a Pro-drop language? In Francis Byrne & John Holm (eds.), Atlantic meets Pacific. A global view of pidginization and creolization, 71-90. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York, NY: W.W. Norton Dryer, Matthew S. (1989). Discourse-governed word order and word order typology. Belgian Journal of Linguistics 4: 69-90 Elman, Jeffrey L. (1990). Finding structure in time. Cognitive Science 14: 179-211 Erbaugh, Mary S. (1983). Why Chinese children's acquisition of Mandarin predicates should be "just like English". Papers and Reports on Child Language Development 22: 49-57 — (1986). Taking stock: The development of Chinese noun classifiers historically and in young children. In Colette Grinevald Craig (ed.), Noun Classes and Categorization, 399-436. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Gil, David (1994). The structure of Riau Indonesian. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 17: 179-200 — (2003). English goes Asian: Number and (in)definiteness in the Singlish noun phrase. In Frans Plank (ed.), Noun phrase structure in the languages of Europe, 467-514. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter Gilligan, Gary Martin (1987). A Cross-Linguistic Approach to the Prodrop Parameter. Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California Hawkins, John A. (2002). Symmetries and asymmetries: their grammar, typology and parsing. Theoretical Linguistics 28: 95-150 Huang, C.-T. James (1984). On the distribution and reference of empty pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 15.4: 531-574 — (1989). Pro-drop in Chinese: A generalized control theory. In Osvaldo Jaeggli & Kenneth J. Safir (eds.), The Null Subject Parameter, 185214. Dordrecht: Kluwer Huang, Yan (1995). On null subjects and null objects in generative grammar. Linguistics 33: 1081-1123 Jaeggli, Osvaldo and Kenneth J. Safir (1989). The Null Subject parameter and parametric theory. In Osvaldo Jaeggli & Kenneth J. Safir (eds.), The Null Subject Parameter, 1-44. Dordrecht: Kluwer Kouwenberg, Silvia (1990). Complementizer pa, the finiteness of its complements, and some remarks on empty categories in Papiamento. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 5.1: 39-51 Li, Charles N. and Sandra A. Thompson (1981). Mandarin Chinese. A Functional Reference Grammar. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press Li, Ping, Elizabeth Bates and Brian MacWhinney (1993). Processing a language without inflections: A reaction time study of sentence interpretation in Chinese. Journal of Memory and Language 32: 169192 Li, Ping, Curt Burgess and Kevin Lund (2000). The acquisition of word meaning through global lexical co-occurrences. In Eve V. Clark (ed.), Proceedings of the Thirtieth Stanford Child Language Research Forum, 167-178. Stanford, CA: Center for the Study of Language and Information Lupyan, Gary and Morten H. Christiansen (2002). Case, word order, and language learnability: Insights from connectionist modeling. In Wayne Gray & Christian Schunn (eds.), Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 596-601. McWhorter, John H. (1998). Identifying the creole prototype. Vindicating a typological class. Language 74.4: 788-818 Meyerhoff, Miriam (2000). The emergence of creole subject-verb agreement and the licensing of null subjects. Language Variation and Change 12: 203-230 Miao, Xiaochun and Manshu Zhu (1992). Language development in Chinese children. In Hsuan-Chih Chen & Ovid J.L. Tzeng (eds.), Language Processing in Chinese, 237-276. Amsterdam: North-Holland Muysken, Pieter and Paul Law (2001). Creole studies. A theoretical linguist's field guide. Glot International 5.2: 47-57 Siewierska, Anna (1996). Word order type and alignment type. Zeitschrift für Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung 49.2: 149-176 — (1998). Variation in major constituent order: a global and a European perspective. In Anna Siewierska (ed.), Constituent Order in the Languages of Europe, 475-551. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter Tao, Hongyin (1996). Units in Mandarin conversation. Prosody, discourse, and grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Tardif, Twila, Marilyn Shatz and Letitia Naigles (1997). Caregiver speech and children's use of nouns versus verbs: A comparison of English, Italian, and Mandarin. Journal of Child Language 24: 535-565 Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman (1988). Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press Tomlin, Russell S. (1986). Basic Word Order. Functional Principles. London: Croom Helm Trueswell, John C., Irina Sekerina, Nicole M. Hill and Marian L. Logrip (1999). The kindergarten-path effect: studying on-line sentence processing in young children. Cognition 73: 89-134 Van Everbroeck, Ezra (1999). Language type frequency and learnability: A connectionist approach. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 755-760. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum — (2003). Language type frequency and learnability from a connectionist perspective. Linguistic Typology 7.1: 1-50