NOV 25 XtOrIatiX *6.

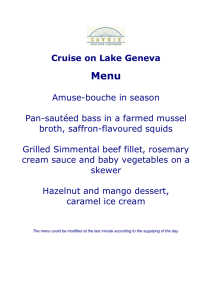

advertisement