Retrieval strategies for tutorial stories* Robin Burke

advertisement

From: AAAI Technical Report WS-93-01. Compilation copyright © 1993, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

Retrieval strategies for tutorial stories*

Robin Burke

Institute for the LearningSciences

1890 Maple Ave., Evanston IL 60626, USA

burke@ils.nwu.edu

suggestions, to namejust a few possibilities. This paper

describes in detail three of the retrieval strategies that are

used to produce SPIEL’s storytelling

behavior. Each

involves a comparisonbetweena story and the situation in

which it might be told, a comparisonthat differs according

to the needs of the educational context. SPIEL’sretrieval

strategies select different subsets of features froma story’s

index and use a variety of measurements of fitness

including similarity, dissimilarity and other kinds of

relations.

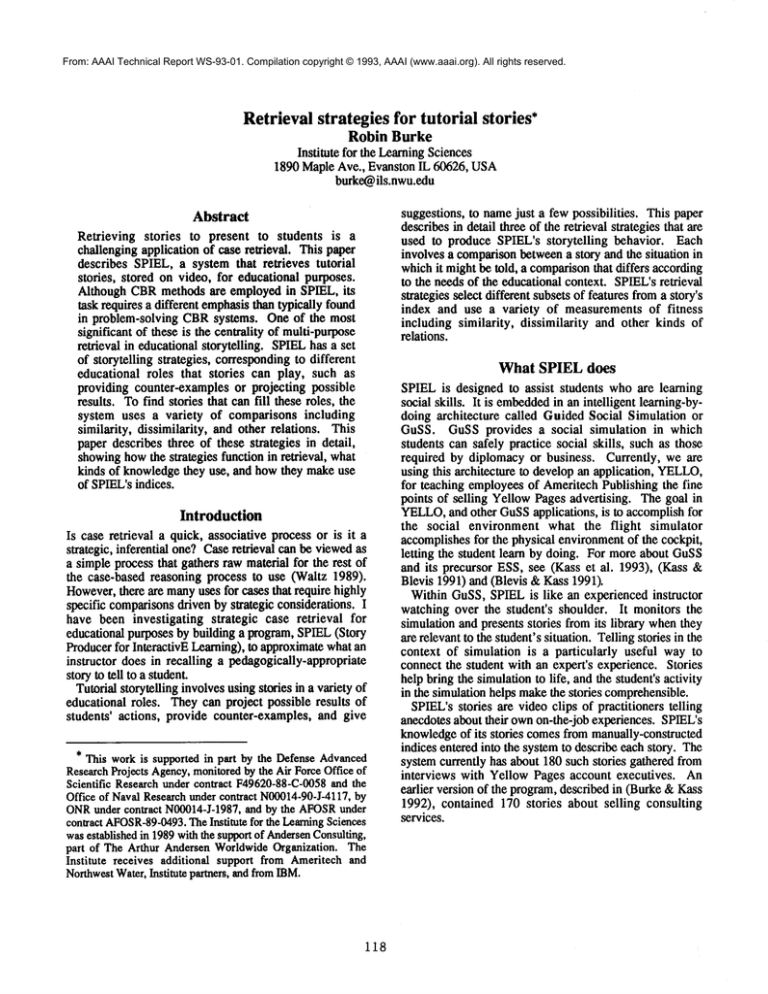

Abstract

Retrieving stories to present to students is a

challenging application of case retrieval. This paper

describes SPIEL, a system that retrieves tutorial

stories, stored on video, for educational purposes.

Although CBRmethods are employed in SPIEL, its

task requires a different emphasisthan typically found

in problem-solving CBRsystems. One of the most

significant of these is the centrality of multi-purpose

retrieval in educational storytelling. SPIELhas a set

of storytelling strategies, corresponding to different

educational roles that stories can play, such as

providing counter-examples or projecting possible

results. To find stories that can fill these roles, the

system uses a variety of comparisons including

similarity, dissimilarity, and other relations. This

paper describes three of these strategies in detail,

showinghowthe strategies function in retrieval, what

kinds of knowledgethey use, and how they make use

of SPIEL’sindices.

What SPIEL does

Introduction

Is case retrieval a quick, associative process or is it a

strategic, inferential one? Case retrieval can be viewedas

a simple process that gathers raw material for the rest of

the case-based reasoning process to use (Waltz 1989).

However,there are manyuses for cases that require highly

specific comparisonsdriven by strategic considerations. I

have been investigating strategic case retrieval for

educational purposes by building a program, SPIEL(Story

Producer for Interactive Learning), to approximatewhat an

instructor does in recalling a pedagogically-appropriate

story to tell to a student.

Tutorial storytelling involves using stories in a variety of

educational roles. They can project possible results of

students’ actions, provide counter-examples, and give

* This workis supported in part by the DefenseAdvanced

ResearchProjects Agency,monitoredby the Air ForceOffice of

Scientific Research under contract F49620-88-C-0058

and the

Office of NavalResearchunder contract N00014-90-J-4117,

by

ONRunder contract N00014-J-1987,and by the AFOSR

under

contract AFOSR-89-0493.

The Institute for the LearningSciences

wasestablished in 1989with the supportof AndersenConsulting,

part of The Arthur Andersen WorldwideOrganization. The

Institute receives additional support from Ameritech and

NorthwestWater,Institute partners, and fromIBM.

118

SPIEL is designed to assist students who are learning

social skills. It is embedded

in an intelligent learning-bydoing architecture called Guided Social Simulation or

GuSS. GuSS provides a social simulation in which

students can safely practice social skills, such as those

required by diplomacy or business. Currently, we are

using this architecture to develop an application, YELLO,

for teaching employees of Ameritech Publishing the fine

points of selling Yellow Pages advertising. The goal in

YELLO,

and other GuSSapplications, is to accomplish for

the social environment what the flight simulator

accomplishes for the physical environment of the cockpit,

letting the student learn by doing. For more about GuSS

and its precursor ESS, see (Kass et al. 1993), (Kass

Blevis 1991) and (Blevis &Kass 1991).

Within GuSS, SPIEL is like an experienced instructor

watching over the student’s shoulder. It monitors the

simulation and presents stories from its library whenthey

are relevant to the student’s situation. Telling stories in the

context of simulation is a particularly useful way to

connect the student with an expert’s experience. Stories

help bring the simulation to life, and the student’s activity

in the simulation helps makethe stories comprehensible.

SPIEL’sstories are video clips of practitioners telling

anecdotes about their ownon-the-job experiences. SPIEL’s

knowledgeof its stories comes from manually-constructed

indices entered into the systemto describe each story. The

system currently has about 180 such stories gathered from

interviews with Yellow Pages account executives. An

earlier version of the program, described in (Burke &Kass

1992), contained 170 stories about selling consulting

services.

Standard problem-solvinl~

Story retrieval in SPIEL

Incremental

Beforeretrieval

Cue composition

Relrieval criteria

Solves a similar problem

Makesan educational point

Case structure

Represents problem solution

Video clip

No

Yes

Mandator~retrieval

Yes

No

Case evaluation

Between-case competition

Yes

No

Table 1. Differences betweencase retrieval in _oroblem-solvingCBRand story retrieval in SPIEL

Story retrieval vs. case retrieval

Educational tasks emphasize different requirements for

case retrieval than most problem-solving tasks. Table 1

summarizes some of the most important differences in

emphasis.

Cue composition: One of the major differences between

SPIEL and the standard problem-solving CBRmodel

(Kolodner & Jona 1992) is the way retrieval cues are put

together. CBRsystems create a retrieval cue by analyzing

a statement of the problem to be solved. SPIELretrieves

its stories based on a continuous stream of actions by the

student and the GuSSsimulation. Anyevent in the history

of the interaction could be relevant to the retrieval of a

tutorial story. So, SPIELhas to build its retrieval cues

incrementally throughout this on-going process.

Mandatoryretrieval: A case-based problem solver

must retrieve something, otherwise there will be no basis

for building a solution. If what is retrieved is not a

directly-applicable solution, it can be adapted. However,

in teaching, there are manystudent states for which there

will be no appropriate story to tell. Becauseit cannot adapt

its stories, SPIELhas to retrieve only closely-relevant

ones. A story that is far afield from the student’s

immediate concerns will be confusing. If SPIEL cannot

find a very good story, it is better off waiting for the

student to do something else. Usually, there is an

appropriate story about once every 10-20 student actions.

Case evaluation: In the standard CBRmodel, the

retrieval step uses indices to retrieve a set of candidate

cases. The candidate cases themselves are then examined

and evaluated, and the best case is chosenas the basis for a

problem solution. The evaluation step enables the system

to reject inappropriately retrieved cases. SPIELhas no

language capacity with which to understand or evaluate the

video clips it retrieves. It must retrieve conservatively,

because whatever is retrieved will be presented to the

studenL

Between-casecompetition: Educational stories are not

in competition to be the single right answer, as in many

retrieval models,such as (Thagardet al. 1990). If there are

stories from experts with opposing viewpoints on the

student’s situation, SPIELneeds to showthe student the

whole range of opinion by making all retrieved stories

available.

These differences have three notable consequences for

the designof a tutorial case retriever.

119

Because SPIEL does not have access to the content of

what it is retrieving, the index has to contain everything

that the system will need to decide to tell the story. It

needs indices that are more detailed and complex than

those typically used in case retrieval.

There is an implicit theory of problem solving in the

similarity metrics found in problem-solving CBR:the more

similar the input problem is to the problemsolved by the

case, the morelikely it is that the solutions will also be

similar. SPIEL’sretrieval strategies also embodya theory

of good cases for the educational context. They involve

different kinds of judgmentsfrom those found in similarity

metrics.

In SPIEL,a tutorial opportunity is defined as a situation

for which there is a relevant story to tell. It does a

storyteller no goodto recognize a goodtime to tell a story

it doesn’t have. A similar insight was behind the design of

ANON(Owens 1990), which used its case base

determine what features to search for in the input problem.

SPIEL uses its story base in a similar way to guide the

search of the events in the simulation.

The rest of this paper focuses mainly on retrieval

strategies,

but I touch briefly on the indexing and

implementationissues to put the strategies in context.

Implementingstorytelling strategies

One way to think about the problem an educational

storyteller faces is to think of each story as a possible

lesson and each strategy as a way to teach it. Storytelling

strategies indicate the conditions under which the goal of

telling a story can be achieved. Since a storyteller has

manystories, any one of which could be relevant at any

time, it is useful to think of it as an opportunisticsystem.

However,educational storytelling is not as open-ended

as the general case of opportunism whose complexities

were laid out in (Birnbaum 1986). SPIEL’s storytelling

strategies comparestories about an activity to specific

contexts of student action. They seek coherence and

relevance, not distant analogies. It is possible to describe

concretely what an opportunity to tell a story using a

particular strategy wouldlook like.

SPIELalso has a strong advantage over the problem of

opportunism in that it is embeddedin a simulation. No

truly novel actions can occur in GuSSsince the student is

constrained by the program’s interface and the simulation

operates in known ways. SPIEL knows with certainty

what actions can and cannot happenin its world.

Storage

generation

~ IMic~~ St°rytelling

I strategies

Opportunity-recognition

rules

Retrieval

C

Opportunity-recognition

rules

Retrieved

Eventsfrom---{~1 Marcher

~- story/strategy

simulation

I

I

Language

generat~

Story with bridge andcoda

Figure 1. SPIEL’sprocessing

SPIEL’s problem of opportunism is therefore much

simpler than the general one. The simulated world

provides a limited space in which events can occur;

storytellingstrategies single out preciseareas of the space

that constitute opportunities. Theseproperties enable

SPIELto use what Birnbaumcalls the "elaborate and

index" modelof opportunism:

...spend someeffort, whena goal is formed, to

determinea numberof situations in whichit mightbe

easily satisfied...and then indexthe goal in termsof

all the features that mightarise in suchsituations.

(pg. 146)

SPIELworksfrom its database of stories to determine

whatis an opportunityfor intervention.Its processingcan

be dividedinto two phases: storage time, whennewstories

are put into the system and the systemconsiders howit

mighttell them;andretrieval time, whena studentinteracts

with the GuSSsystem and and SPIEL watches for

opportunities to give tutorial feedback. Figure 1 shows

these phases.

At storagetime:

1. Indicesare attachedto eachstory in the database.

2. SPIEL’sstorytelling strategies are applied to each

index.If the strategyis applicableto the index,a set

of rules is generated that will recognize an

opportunityto tell that story using the storytelling

strategy.

Atretrieval time:

1. Opportunity-recognition

rules are matchedagainst the

state of the simulation.

2. Whenthe rules for a particular combinationof story

andstrategymatchsuccessfully,the story is retrieved.

120

.

After retrieval, natural languagebridgeand codaare

generatedto integrate the story into the student’s

current context.

Indices for educational stories

SPIEL’sindices are created manually.Sincethe stories are

in video form, automaticprocessing wouldentail speech

(and possibly gesture) recognition as well as natural

languageunderstanding.SPIEL’sdesigntherefore calls for

a humanindexerto watcheach story being told and use an

indexing tool to compose indices that capture

interpretationsof the story’s meaning.

Theseinterpretations havethe general form, "Xbelieved

Y, but actually Z," which is a form of anomaly. An

anomaly is a failure of expectation that requires

explanation (Schank 1982). Typically, anomalous

occurrencesare whatmakestories interesting and useful,

and they are a natural wayto summarizewhat a story is

about. Anomalies

are especially importantin stories about

social activity since students are learning what

expectations they should have and how to address

expectationfailures.

The anomaly forms the core of SPIEL’s indexing

representation. Considerthe story transcribed here whose

indexis shownin Figure2.

I wentto this auto glass place onetime whereI had

the biggest surprise. I walkedin; it wasa big, burly

man; he talked about auto glass. So we were

workingon a display ad for him.

It waskind of a rinky-dinkshop and there wasa TV

playing and a lady there watchingthe TV.It was a

soap operain the afternoon.I talked to the mana lot

but yet the womanseemedto be listening, she was

Setting: step-of-sales-process(salesperson,

pre-call)

business-type(service)

business-size(small)

business-partnership(auto-glass

man,wife)

marded(auto-~lass

man,wife)

sales-target(salesperson,autc-~lass company)

Anomaly:l salesperson [ assumed

ii MeI

theme I

Assumed ~

’ Actual

Theme: housewife

business panner

Goal: hospitalit~

help in decision

Plan: small

talk

evaluatepresentation

Result:

positive evaluation

Pos.side-effect:

sale for salesperson

Neg.side-effect:

Fit, ure 2. Indexfor "WifewatchingTV"story_

asking a couple of questions. She talked about the

soapoperaa little bit andaboutthe weather.

It turns out that after he and I workedon the ad, he

gaveit to her to approve.It turns out that after I

broughtit backto approve,she approvedthe actual

dollar amount.Hewas there to tell me about the

business, but his wife wasthere to hand over the

check.

So if I hadignoredher or had not givenher the time

of day or the respect that she was deserved, I

wouldn’thave madethat sale. It’s important when

youwalkin, to really listen to everyoneandto really

payattention to whateveris goingon that yousee.

Theindex contains

¯ the anomalyin the story, whichcan be phrased as

"the salesperson assumedthe wife wouldhave the

role of housewife,but actually she was a business

partner."

¯ the setting, the story’s position within the overall

social task, includinga representationof the social

relationshipsbetweenthe actors in the story, and

¯ intentional chains surrounding and explaining the

anomalousoccurrences.

SPIEL’sindices are considerably more complexthan

those typically found in case-based reasoning systems.

Thefact that SPIEL’scases are video clips is part of the

reason. Its indices have to say everything that SPIEL

needsto knowaboutits stories since the stories themselves

cannot be evaluated. Anotherreason that SPIEL’sindices

showcomplexityis the task of educational storytelling

itself. SPIELhas a variety of reasonsfor telling stories,

each of whichrequires a slightly different perspectiveon

the index. SPIELneeds complexindices to meet the

demands

of a variety of strategies. Thethree strategies I

describe next showsomeof these uses. Theothers can be

foundin (Burkein preparation).

121

The Warn about plan storytelling

strategy

Astorytelling strategy is a wayof using a story to teach.

Consider Example1, which shows the Warnabout plan

strategy in action. Thestudent is pressing for a large ad

campaign,muchlarger than the client needsor can really

afford. The customeris an evasive type, and does not

immediately

reject the idea: instead, he stalls. Thestudent

couldlose a lot of time in a futile effort to makethis sale.

At this point, the storyteller interveneswith a story about

an analogoussituation where, instead of stalling, the

customer rejected the ad program and rebuked the

salesperson. Telling the story at this point helps the

student identify the problembefore goingtoo far along in

this direction.

Anaccurate assessmentof howfar to let the student go

wouldrequire a great deal of knowledge

about the scenario

the student is engagedin, moreknowledge

than is available

to SPIEL.GuSS’sopen-endedsimulation design does not

allow any quick read-out of what outcomesare likely and

howfar awaythe student is from obtaining them. SPIEL

would have to perform a complete envisionment of

possible simulationoutcomesto find out, moreprocessing

than can be accomplished in the midst of student

interaction. Instead, SPIELuses prototypical knowledge

about inconclusive outcomes. For SPIELto tell the

"Wouldyou buy this ad?" story in the example,it must

knowthat overcoming

the customer’sstall in this kind of

case is time-consuming

andnot particularly educational.

At storagetime, eachstorytelling strategyselects stories

that are compatiblewith its educationalrole. Astory with

a good outcomecould not be sensibly used with Warn

about plan, for example. The second task of the

storytelling strategy is to generate, for each compatible

story, a Recognition Condition Description (RCD),

representationthat describesa situation in whichthe story

¯ Thestudent doesn’t gather very muchinformationat the

pre-call stage.

¯ Backat the office, the studentpreparesa very large ad

campaign.

¯ Whenthe student presents this to the client, the client

says"Youknow,I really haveto talk to Edaboutthis..."

and is inwardly very doubtful of the value of such a

large expenditure.

Storyteller: Astory abouta failure in a situation similar to

yours...

Youmadea recommendationthat was muchlarger than

Dave’sexpectations. Here is a story in whichdoing that

led to problems:

"I remember

myfirst year 1970.I wason myfirst Yellow

Pagesales canvass. In those days, they didn’t give youa

lot of time to showability andI wasn’tdoingvery well.

Mymanagertold methat I hadone weekto start producing

or they weregoingto let mego.

"I called on a graphicartist in Indianapolis.Hehada 2HS,

a one-inchad. I walkedin, askedtwominorquestions, and

I laid downa quarter-pagepiece of spec in front of this

manand told him he needed this ad. The manlooked at

meandhe said, ’Would

youbuythis ad?’ Heturnedit right

back to me. I didn’t knowwhat to say. It shockedme.

Finally, I said, ’No, I wouldn’t.’Hedidn’t needa quarter

page; a one-inch ad is what he needed. The gentleman

proceededto give it to me,up oneside anddownthe other.

Hetold methat I was there for myowngreedyinterests,

trying to makecommissions

instead of taking care of his

advertisingand caring abouthim. Hesaid, ’If you’reever

goingto makeit in this business,you’dbetter start paying

attention to yourcustomers.’

"I walkedout of that call a different salesmanbecauseI

realized then that the only wayto sell YellowPagesis to

sell whatthe customerneeds, not what I need. Learning

that lesson tamedmysales career around.I started making

sales, andby the end of the canvass,I wasoneof the top

producers."

Youmadea recommendation

that is muchlarger than the

client’s expectations.Thatmightnot be a goodidea.

Example1. Telling "Wouldyou buy this ad?"

using the Warn

aboutnlan strategy

could be told using the strategy, a tutorial opportunity

providedby the story.

Computingthe RCDinvolves makinginferences based

on the story’s index, essentially askingthe question"What

wouldhave to happenfor this story to be goodto tell?"

The answer to this question is different for every

storytelling strategy. For Warnabout plan, the situation

shouldbe pretty muchthe sameas in the story: the student

should have overshot the markby designing a large ad

program.The difference is that the student should be

unlikelyto discoverthis error. Immediate

rejection, which

is the bad outcomeof the story, is not what should be

looked for. Instead, the system needs an inconclusive

outcome

that bodesill.

Whatoccurs in Example1 is one kind of outcomeof this

kind: if the personthe studentis talkingto has authorityto

122

buy and that person defers the decision to someoneelse,

this is usually an evasive maneuver,not motivatedby a

real needfor consultation.Also, if the customerdelaysthe

decision:"I don’thavelime for this now.Let’s talk aboutit

next week."Neitherof these objectionsare associatedwith

any of the importanteducational goals of the system, so

interventionis justified.

A descriptionof the RCD

that characterizes the tutorial

opportunitywouldthereforelook somethinglike this:

WHEN

the student is closing the sale andspeakingto

someonewhois the decision maker,

LOOK

FORthe student to present a very large

ad program,

the client to havea negativebelief about

that program,and

the client to defer the decisionto another,

or the client to put the decisionoff to

anothertime,

THENTELL"Wouldyou buy this ad?"

ASa "Warnabout plan" story.

This is the formatof an RCD.It contains a trigger (the

"when"part) that describesthe conditionsunderwhichthe

opportunity becomespossible, usually a function of the

stage of the sales processthat the studentis in, combined

with characteristics of the other agents involvedin that

stage. If the triggeringconditionsare met,the systemtries

to gather evidencethat similar intentionsare at workin the

simulation.

Warnabout plan can also be used to showeffects that

wouldnot appear within the scenario. For example,scare

tactics maypersuadea customerto buy once, but they hurt

the client relationship and eventually result in lost

business. This problemdoes not showup in YELLO

since

a scenario ends whenthe student makes one sale. A

student whosuccessfullyuses this tactic in the simulation

might think it is a good idea in general unless the

storyteller can showan exampleto demonstrateotherwise.

Another use of the storytelling strategy is in the

generationof the natural languagetexts that surroundand

explain the story. As shownin Example

1, there are three

parts to the explanation:the headline, for the attentiongetting initial statement; the bridge, the introductory

paragraphexplaining whythe story has comeup; and the

coda, that closes the story presentation with a

recommendation

or evaluation. Eachstrategy has a set of

natural languagetemplatesfor these texts, whichare filled

in by generatingappropriatephrasesat retrieval time.

The Demonstrate risks storytelling

strategy

There is tremendousvariability in the social world.

Approachesthat have always workedmayfail in a new

situation for no apparentreason; unlikely strategies may

fortuitously succeed.Bothin GuSS’ssimulator andin real

life, the learner gets to see only one outcomeat a time.

Oneimportantrole that real-world stories can play is to

illustrate the range of real experience by presenting

counter-examplesthat contrast with what is happeningto

the student. Studies of apprenticeshipsituations indicate

that experts often use stories in exactly this way(Lave

Wenger1991).

TheDemonstraterisks strategy showsthat a successful

result in the simulationis not alwaysrepeatablein the real

world. Considerthe situation wherethe student closes a

sale, but continuesconversingwith the customer.This is

risky, since it gives the customer an opportunity to

reconsider. To show the risk, SPIEL tells about a

salespersonwholost a sale througha careless remarkmade

after a sale wasclosed.

This strategy resembles Warnabout plan because it

uses a story about a failure to warn the student. The

difference is that the Warn

aboutplan strategy is used

whenthe simulation is not likely to give immediate

feedback about the student’s actions. The Demonstrate

risks strategy looksfor the simulationgivingfeedback,but

of the wrongkind. It waits for the simulation to do

somethingopposite from the outcomefound in the story,

and tells a story to show howthe real world can be

different fromthe simulation.

This approachto retrieving counter-examplesdiffers

from existing CBRsystemsthat use contrasting examples,

such as HYPO

(Ashley & Rissland 1987). HYPO

retrieves

cases based on similarity along certain dimensionsand

buildsa structure, the claimlattice, of the retrievedcases,

enablingit to identify contrasts along other dimensions.

SPIELuses its knowledgeof contrasts in the retrieval

processitself, so that it onlyretrievesthosecasesthat make

the needededucationalpoint.

To arrive at the recognition condition description for

such a tutorial opportunity,SPIELmustlook for a result

that wouldbe opposite fromwhatoccursin the story. The

story described aboveshoweda salespersonlosing a sale

during conversationafter the close of a sale. SPIELuses

an opposite-finding inference mechanismto identify a

outcomewhich is opposite from the one shownin the

story. Thestory is a goodcounter-example

if the student

doesa similar action, but doesnot lose anything.

The "Warn about assumption" strategy

Newcomersto a social domain may inappropriately

transfer expectationsfromthe rest of their social lives. A

newsalespersonmaythink, for example,that a friendly,

talkative customeris morelikely to buythan a "get down

Storytellingstrategy Summary

Tell a story aboutan unsuccessfulplan

Warnabout plan

whenthe student has begunexecutinga

similar plan.

Demonstraterisks

Warnabout

assumption

to business"type, whenin manycases, the oppositeis true.

Sincethe indices usedfor stories incorporatethe difference

betweena person’s view of the world and howthe world

actually turned out to be, SPIELis well poised to help

studentsby pointingout their unrealisticexpectations.

If the programhas evidence that the student has a

particular assumption, the Warnabout assumption

strategy calls for it to tell a story about a time whena

similar assumptionwas wrong.Supposethe student has an

opportunityto gather informationabout a client’s business

fromthe client’s spouse,but doesnot take that opportunity.

It is reasonableto infer that the student assumesthat the

spouse does not have an importantrole in the business.

SPIELcan tell the "WifewatchingTV"story at this point,

showinga case wherea similar assumptionprovedwrong.

I call this type of strategy is a perspective-oriented

strategy, becausewhat is important is the contrasting

perspective in a story. Recognizingstories that are

relevant in this wayis moredifficult than recognizing

stories that contain similar actions. Perspective-oriented

strategies need knowledgeabout howcertain actions are

characteristic indicators of the student’s mentalstate.

Students do not alwaysact in waysthat clearly indicate

their beliefs, but if they do, the systemshouldbe prepared

to respond. In this story, the salespersonassumes,in an

information-gathering

context, that the client’s spousewill

not havea business role. Whatactions wouldindicate such

an assumption on the student’s part? In information

gathering, the primarytask is to ask questions about the

client’s business.If the studentfails to ask suchquestions

of someonewhengiven the opportunity, this is a good

indicationof an assumption

on the student’spart that there

is no information to gather. Anotherpossible indicator

wouldbe a deliberate act on the student’s part to exclude

the spousefromthe sales presentation.

Conclusion

Thethree storytelling strategies describedin this paperand

summarized

in Table 2 showsomeof the demandsthat the

task of educationalstorytelling places on a case retrieval

system. The retriever must not only respond to crucial

similarities between

a story andthe situation in whichit is

told, but also differences, such as opposite outcomesas

called for by the Demonstrate risks strategy, and

Tutorial opportunity

Lookfor similar setting, similar

goal andsimilar plan.

Lookfor a negative, but

inconclusive outcome.

The negative

Lookfor similar setting, similar

Tell a story abouta negativeresult of a

outcomeof a plan. goal andsimilar plan.

particular plan whenthe studenthas just

Lookfor an opposite outcome.

executeda similar plan but hadsuccess.

Tell a story aboutan erroneousassumption An assumptionthat Lookfor similar setting.

didn’t hold.

Lookfor actions that are

that someonemadewhenthe student

appears to have madethe sameassumption.

indicative of the assumption.

Table2. Summary

of the three storytelling strategies

123

Storyis about:

The negative

outcomeof a plan.

evidential relations, used by Warnaboutassumption

and

other perspective-orientedstrategies that look for actions

that indicatebeliefs.

Thedesign of SPIELis a responseto these demands.It

uses structured, strategic comparisons

betweenstories and

the situations in whichthey are told. Theseretrieval

strategies are an explicit counterpartto whatis implicit in

the similarity metrics used in standard problem-solving

case retrieval: a theory of whatcases are useful for the

task. Extensionsof the standardproblem-solving

paradigm

(Kolodner, 1989) and newapplications for case-based

reasoning technology, such as education, entail new

notions of utility, and with them,newmetrics that combine

similarity judgmentsandother measuresof fimess.

Putting such strategies to workneed not render case

retrieval prohibitively inefficient. Since strategies are

implementedas proceduresthat operate at storage time,

SPIELperformsa minimum

of inference at retrieval time,

yet still remainssensitive to the strategic considerations

involvedin recognizingtutorial opportunities.

Acknowledgments

The GuSSproject has prospered under the guidance of

RogerSchank,Alex Kass and Eli Blevis. I wouldlike to

acknowledge

their contributionto the ideas in this paper.

GuSSis the product of manymindsand efforts including

those of Mark Ashba, Greg Downey,Debra Jenkins,

SmadarKedar, Jarret Knyal, MariaLeone,Charles Lewis,

John Miller, Thomas Murray, Michelle Saunders,

JeannemarieSierant, and MaryWilliamson.Thesales and

sales training organizationsof AmeritechPublishinghave

also contributedto this researchin manyways.

References

Ashley,K., and Rissland, E. 1987. Compare

and Conlrast,

ATest of Expertise. In Proceedingsof the 6th National

Conference

on Artificial Intelligence. AAAI.

Birnbaum,L. A. 1986. Integrated Processing in Planning

and Understanding. PhD thesis, Dept. of Computer

Science,YaleUniversity.

Blevis, E. andKass, A. 1991.Teachingby Meansof Social

Simulation.In Proceedingsof the International Conference

on the LearningSciences. AACE.

Burke, R. 1992. Knowledge

acquisition and education: a

case for stories. In Proceedings of the Symposium

on

Cognitive Aspectsof Knowledge

Acquisition. AAAI.

Burke, R. in preparation. Representation, Storage and

Retrieval of Stories in a GuidedSocial Simulation. PhD

thesis, Dept. of EECS,

Northwestern

University.

Burke,R. and Kass,A. 1992.Integrating CasePresentation

with Simulation-basedLearning-by-doing.In Proceedings

of 14th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science

Society, 629-634.Hillsdale, NJ: LawrenceErlbaumAssoc.

Domeshek,E. 1992. Do the Right Thing: A Component

Theoryfor IndexingStories as Social Advice.PhDthesis,

Dept. of ComputerScience, Yale University. Issued as

124

Technical Report No. 26, Institute for the Learning

Sciences.

Edelson, D. 1993 Learning from Stories: Indexing,

Remindingand Questioning in a Case-based Teaching

System. PhD thesis, Dept. of EECS, Northwestern

University.

Gentner, D. and Forbus, K. 1991. MAC/FAC:

A Modelof

Similarity-BasedRetrieval. In Proceedingsof 13th Annual

Conferenceof the Cognitive Science Society. Hillsdale,

NJ: LawrenceEflbaumAssoc.

Hammond,K. 1989. Case-based Planning: Viewing

Planningas a Memory

Task. Boston: AcademicPress.

Kass, A. and Blevis, E. 1991. Learning Through

Experience: An Intelligent Learning-by-DoingEnvironment for Business Consultants. In Proceedings of the

Conference on Intelligent Computer-AidedTraining.

NASA.

Kass, A.; Burke, R.; Blevis, E.; and Williamson,M. 1993.

Constructing Learning Environmentsfor ComplexSocial

Skills. Journalof the LearningSciences.Toappear.

Kolodner,J. 1989. JudgingWhichis the ’Besf Casefor a

Case-basedReasoner. In Proceedings of the Case-Based

Reasoning Workshop. DARPA/ISTO.

Kolodner,J. and Jona M. 1992. Case-basedReasoning.In

Encyclopedia

of Artificial Intelligence(2nded.), S. Shaprio

(ed.). NewYork: Wiley.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. 1991. Situated Learning:

legitimate peripheral participation. NewYork:Cambridge

UniversityPress.

Owens,C. 1989. Integrating Feature Extraction and

MemorySearch. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual

Conferenceof the Cognitive Science Society. Hillsdale,

NJ: LawrenceErlbaumAssoc.

Schank, R. C. 1982. Dynamic Memory: A Theory of

Learning in Computersand People. NewYork: Cambridge

UniversityPress.

Schank, R. C. 1991. Tell Mea Story. NewYork: Charles

Scribner’sSons.

Stevens, S. 1989.Intelligent Interactive VideoSimulation

of a CodeInspection. Communications

of the ACM,32(7),

832-843.

Thagard, P.; Holyoak,K.; Nelson, G.; and Gochfeld,D.

1990.Analogretrieval by constraintsatisfaction. Artificial

Intelligence, 46(3): 259-310.

Waltz, D. L. 1989. Is Indexing Usedfor Retrieval7 In

Proceedings of the Case-Based Reasoning Workshop,

DARPA/ISTO.

Williams,S. M. 1993.Putting Case-Based

Instruction into

Context: Examplesfrom Legal, Business, and Medical

Education.Journalof the LearningSciences. To appear.