Document 13737247

advertisement

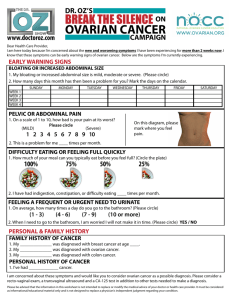

7/2/15 I have no financial rela.onships to disclose. Approach to imaging of pelvic pain • To emphasize the importance of ultrasound as the imaging modality of choice for the most commonly presen6ng diagnoses in the se7ng of acute and chronic pelvic pain in gynecology • Discuss imaging findings and an imaging approach useful in making the diagnosis • Discuss the role of imaging, primarily sonography, in the management of acute and chronic disease • Acute pain is intense pain characterized by sudden onset. • Chronic pain is non-­‐cyclic pelvic pain that lasts 6 months or longer which is severe enough to cause func6onal disability or the need for medical care. Acute pelvic pain Chronic pelvic pain Dysmenorrhea Pain associated with the menstrual cycle Dysmenorrhea 1 7/2/15 • In a specific situation, if the clinician is considering an imaging study, what study (or studies) are most likely to provide the necessary information? • Provides this information for various clinical problems based on the best available clinical data • Sonography the modality of choice and usually only modality necessary for a suspected gynecologic or obstetric abnormality • MRI as problem solving tool for suspected GYN abnormality • CT “may be appropriate” for GYN abnormality but more useful for a GI or GU abnormality although MRI is favored over CT in the pregnant pa6ent Determined by clinically suspected differential diagnosis following careful evaluation! • Reproductive age female presents with pelvic pain and gynecologic etiology is supected • Serum β-hCG is negative 2 7/2/15 • Reproductive age female presents with pelvic pain and non-gynecologic etiology is supected • Serum β-hCG positive Non-invasive Radiation free Cost effective • Transvaginal US (TVS )whenever possible due to better resolution • Transabdominal sonography provides more information when structures are beyond field of view of vaginal probe Sonography gives high resolution anatomic detail of uterus and adnexa! 3 7/2/15 • • • • Displaces bowel Brings structures closer to the transducer Identifies focal areas of tenderness Can use the “sliding organ sign” to separate structures Spectral and color or power Doppler imaging can be used to characterize vascularity to the: – ovaries – fallopian tubes – uterus And narrow the differential considerations Problem-solving tool for specific indications: – If further characterization of a disorder is required – If the patient’s pain fails to resolve becoming more chronic in nature • Should ectopic pregnancy be under consideration? • Is there concern for fetal exposure to ionizing radiation, making ultrasound the initial imaging modality of choice? • Check a serum β-hCG! Negative level essentially excludes the diagnosis of an intrauterine pregnancy and ectopic pregnancy. 4 7/2/15 • • • • • Urgent life-threatening conditions requiring surgical intervention – ectopic pregnancy – appendicitis – ruptured ovarian cyst – ovarian torsion • Fertility-threatening conditions – pelvic inflammatory disease Fever Nausea and vomi6ng Leukocytosis Abnormal vaginal bleeding Functional ovarian cysts Pelvic inflammatory disease Ovarian torsion – ovarian torsion Acute abdominal pain caused by : – large size (> 3 cm) – hemorrhage – rupture or leakage Usually spontaneously resolve following normal menstruation 5 7/2/15 With hemolysis and retraction of clot a reticular network of stranding Is demonstrated 10 days later Fluid-fluid level between fluid components and congealed red blood cells • Peripheral color Doppler signal • No central vascularity Acute hemorrhage is hyperechoic and may be suggestive of a solid mass • A diffuse pattern of low level echoes • More commonly associated with an endometrioma 6 7/2/15 • Inflammation of the endometrium, fallopian tubes, pelvic peritoneum and adjacent structures causing fever, leucocytosis and cervical motion tenderness. • Ascending infection usually by N. Gonnorhea, Chlamydia and superinfecting anaerobes from the vagina • Manifested by tubo-ovarian complexes, peritonitis and abscess formation • Usually bilateral but may be unilateral in patients with IUD’s (most commonly within 3 weeks of insertion) • Lower abdominal pain with no other cause for the illness identified • One or more of the following minimum criteria are present on pelvic examination: Ø cervical motion tenderness Ø uterine tenderness Ø adnexal tenderness Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, August 2014. • Clinical findings nonspecific • Unnecessary antibiotics prescribed • Due to a low threshold for initiating antibiotic therapy • oral temperature >101° F (>38.3° C) • abnormal cervical or vaginal mucopurulent discharge • presence of abundant numbers of WBC on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid • elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate • elevated C-reactive protein • laboratory documentation of cervical infection with N. gonorrhea or Chlamydia 7 7/2/15 • Best “gold standard”: Laparoscopic abnormalities consistent with PID although subtle inflammation may go undetected • Endometrial biopsy with histopathologic evidence of endometritis (may be only sign of PID) The accuracy with which signs and symptoms predict the presence of PID has been evaluated using a laparoscopic "gold standard.” * *Simms I, Warbuton F, Westrom L. Diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease: time for a rethink. Sex Transm Infect 2003;79:491–4 • Transvaginal sonography with Doppler or magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating imaging findings of PID • The data set included women who attended the department of O&G, Lund University Hospital, Sweden, with suspected PID collected between 1960 and 1969. • All patients included in the study had an initial diagnosis based on clinical presentation (signs and symptoms). • A total of 623 patients were included in the analysis; 494 patients were laparoscopically confirmed as having PID and 129 were not. • Three variables significantly influenced the prediction: Ø elevated ESR Ø fever Ø adnexal tenderness • Together, they correctly classified only 65% of women with laparoscopically diagnosed PID. • Can usually only detect complications of PID • Early changes are often subtle although color Doppler may enhance our capabilities Ø Increased vascularity within fallopian tube wall • Difficulty visualizing tubal wall without fluid 8 7/2/15 • In the presence of tubal fluid, common findings include: – wall thickness > 5 mm – incomplete septa – thickening of endosalpingeal folds (cogwheel sign) Thickening of endosalpingeal folds (cogwheel sign) Wall thickening Increased vascularity within fallopian tube wall • Nonspecific findings: – fluid in the endometrial cavity and /or cul-de-sac – ovarian enlargement often with numerous small cysts (“polycystic ovary” appearance) Incomplete septa • Progression of disease with exudation of pus from the distal fallopian tube • An inflammatory mass including the tube and adjacent ovary is formed • The ovary is still visualized as a separate structure • Complete breakdown of architecture • Separate structures are no longer identified ovary Fallopian tube 9 7/2/15 • Retrospective review of 7 studies using US with laparoscopy or endometrial biopsy “gold standard” • Patients with clinical findings of PID • High sensitivity and specificity of 3 findings Romasan and Valentin, Arch Gynecol Obstet (2014) 289:705–714. • ‘‘Thick tubal walls” when tubal walls can be demonstrated • Cogwheel sign (less sensitivity) • Bilateral adnexal masses appearing either as small solid masses or as cystic masses with thick walls Romasan and Valentin, Arch Gynecol Obstet (2014) 289:705–714. • Given the vague and non-specific symptoms, CT is often the first imaging study performed • Thick walled fluid filled fallopian tubes • Difficult to differentiate among pyosalpinx, TOC and TOA • Exposes patients to ionizing radiation, problematic among young women! 10 7/2/15 T2 weighted MRI • May be more accurate than TVS without Doppler* • Highly accurate in abscess evaluation • However, cost, lack of access and limited data preclude widespread use *Ueda H, et.al., Adnexal masses caused by pelvic inflammatory disease: MR appearance.Magn Reson Med Sci. 2002 Dec 15;1(4):207-15. Tubo-ovarian abscess Images courtesy of Dr. Susanna Lee, Dept of Radiology Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Mass. T2 T1 fat sat with contrast • Fluid and inflammation • Wall enhancement • Make the diagnosis • Determine type of management Mild or moderate clinical severity- outpatient therapy yields clinical outcomes similar to inpatient therapy Ø Cefoxitin 2 g IM in a single dose and Probenecid, 1 g orally administered concurrently in a single dose PLUS Ø Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days WITH or WITHOUT Ø Metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 14 days 11 7/2/15 Ø surgical emergencies (e.g., appendicitis) cannot be excluded Ø pregnant patient Ø unresponsive clinically to oral antimicrobial therapy Ø unable to follow or tolerate an outpatient oral regimen Ø severe illness, nausea and vomiting, or high fever Ø tubo-ovarian abscess • With mild or moderate clinical severity, outpatient therapy yields short- and longterm clinical outcomes similar to inpatient therapy • Sonography as well as laparoscopy can visualize extent and severity of disease and determine type of management • Diagnosis strongly considered with abrupt onset of severe unilateral pain • Most commonly seen with associated nausea and vomiting • Pain constant or intermittent • May progress to peritonitis • However: Symptoms may be variable, abdominal pain being the only consistent symptom Ø Cefotetan 2 g IV every 12 hours OR Ø Cefoxitin 2 g IV every 6 hours PLUS Ø Doxycycline 100 mg orally or IV every 12 hours Parenteral therapy can be discontinued 24 hours after clinical improvement and oral therapy continued for 14 days • Classically treated with IV followed by oral antibiotics • If fails, laparoscopy or laparotomy with drainage, BSO and/or hysterectomy • Alternatively, image guided drainage in combination with antibiotics- success rate of 90% reported • Commonly benign ovarian tumors or cysts (50-80%) may act as a fulcrum to potentiate torsion due to increased ovarian volume or weight. • Ovarian hormone induction leading to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and enlargement • Corpus luteum cyst of pregnancy • Hyper mobile adnexa 12 7/2/15 Pampiniform plexus 0varian artery & vein Uterine Artery & vein 1. Lymphatic and venous drainage is compromised 2. Congestion and edema 3. Loss of arterial perfusion Infundibulo-pelvic ligament Utero-ovarian ligament • Can progress rapidly to occlusion of the arterial circulation. • The organ may quickly become very dark black in color due to hemorrhage, necrosis and gangrenous changes Enlarged ovary or ovarian complex Early intervention is key! • Decreases the incidence of complications and improves ovarian salvage rates • The use of pelvic sonography has enhanced our ability to determine when intervention is advisable Irregular internal texture suggesting hemorrhage 13 7/2/15 Assumption: Peripherally placed follicles “Ground glass” pattern centrally consistent with edema Color and spectral Doppler would prove to be an accurate tool for the evaluation of ovarian torsion. In actuality: Doppler findings vary depending on degree of torsion and its chronicity • Lack of arterial and venous signal should enable confident diagnosis • False positive diagnoses may be obtained – Depth of penetration greater than beam capabilities – Improper Doppler or grayscale settings (ie. PRF setting) Ovarian color Doppler signal has been frequently reported in cases of surgically proven torsion! Retrospective series of 39 patients with pathologically proven ovarian torsion performed at Vanderbilt University Medical Center: – 21 (54%) patients had documented ovarian arterial Doppler signal – 13(33%) had documented ovarian venous and arterial signal *Shadinger, Andreotti and Kurian. Preoperative sonographic and clinical characteristics as predictors of ovarian torsion, J Ultrasound in Med 27: 7-13, 2008. 14 7/2/15 • Observation is a reasonable option for smaller masses with benign sonographic characteristics • Surgical management encouraged for larger, >7 cm benign appearing mass –risk of torsion! • Highest risk for torsion in pregnancy-late first trimester & postpartum SAG TRV • Underwent laparoscopic cyst drainage and right oophorectomy with intraoperative finding of a twisted pedicle c/w ovarian torsion • Path report: Luteinized follicular cyst with torsion SAG TRV • An enlarged edematous ovary or ovarian complex is the most consistent finding • Doppler findings vary likely depending on degree and chronicity. • Lack of Doppler flow enables fairly confident diagnosis but ovarian arterial and venous Doppler signal has been reported in a third of surgically proven cases of ovarian torsion.* *Shadinger, Andreotti and Kurian. Preoperative sonographic and clinical characteristics as predictors of ovarian torsion, J Ultrasound in Med 27: 7-13, 2008. 15 7/2/15 • Sonography is initial exam of choice • Computed tomography is being used more frequently Appendicitis most common reason! • Specific sign • Poor sensitivity Thickening of fallopian tube Target sign • The role in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion has not been established. • Similar diagnostic findings have been demonstrated both on MR and CT.* *Rha SE et al. CT and MR imaging features of adnexal torsion. Radiographics 2002; 22(2)283-94. Deviation of uterus Infiltration of fat • Most common GI cause of pelvic pain in women T2 Images courtesy of Dr. Susanna Lee, Dept of Radiology Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Mass. • Marked ovarian enlargement • Heterogeneous, hyperintense pattern due to edema and hemorrhage • Peripherally displaced follicles • Diffuse or periumbilical pain that migrates to the right lower quadrant 16 7/2/15 • CT with contrast imaging modality of choice to confirm diagnosis in non-pregnant female (sensitivity 95%-100% and specificity 87%-98%) • MRI is favored in the pregnant patient • US with graded compression initial imaging test in pregnant females but often inconclusive due to large uterus • MRI next appropriate imaging modality due to lack of ionizing radiation • But US may be an effective substitute with a sensitivity (67%-100%) and specificity (83%-96%) • Blind ended thick walled, tubular, noncompressible, aperistaltic structure • At least 3 mm single wall thickness • Intact echogenic submucosal layer • Surrounding echogenic fat Increased color Doppler vascularity within wall • Enlarged appendix (>6mm) with thickened enhancing wall (>2mm) • Pericecal fat stranding 17 7/2/15 • Similar to CT • A negative oral contrast agent (Gastromark) may be used to demonstrate low signal in bowel and in a normal appendix Acute pain Suspect Gyn cause β-hCG Acute pain Suspect Gyn cause β-hCG Suspect nongyn cause +β-hCG -β-hCG US US or MRI MRI ?CT +β-hCG -β-hCG US Suspect nongyn cause US or MRI CT or US CT or US MRI ?CT 18