TEXAS Forest Legacy Program ASSESSMENT OF NEED

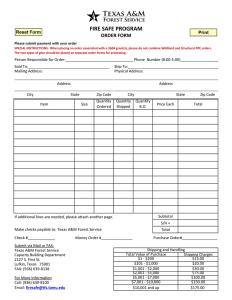

advertisement