From: FLAIRS-01 Proceedings. Copyright © 2001, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

Knowledge Managementand Case-Based Reasoning: a Perfect Match?

lan Watson

AI-CBR

Department of ComputerScience

University of Auckland

Auckland

ian@ai-cbr.org

Abstract

This paper demonstratesthat case-basedreasoningis

ideally suited to the creation of knowledge

management

systems.Thisis becauseof the close matchbetweenthe

activities of the CBR-eycle

and the requirementsof a

knowledge management system. The nature of

kalowledge

withinan organisationis briefly discussed

and the paper illustrates the dynamicrelationship

betweendata, informationand knowledge,showinghow

case-basedreasoningcan be usedto help the manage

the

acquisition and reuse ofknowledge.

1

Introduction

The function of knowledgemanagement(KM)is to allow

an organisationto leveragethe informationresourcesit has

and to support purposefulactivity with positive definable

outcomes (Checkland & Scholes 1990). Knowledgeand

consequently its management

is currently being touted as

the basis of future economiccompetitiveness,for example:

In the information age knowledge, rather than

physical assets or resources is the key to

competitiveness... Whatis newabout attitudes to

knowledgetoday is the recognition of the need to

harness, manageand use it like any other asset.

This raises issues not only of appropriate

processes and systems, but also how to account

for knowledgein the balance sheet (Moran,1999).

Entrepreneursare no longer seen as the ownersof capital,

but rather as individuals whoexpress their tacit knowledge

by "knowing how to do things" (Casson, 1997). Boisot

(1998) sees information as the key organizing principle

the organization; "information organizesmatter."

The introduction of information technology on a wide

scale in the last thirty years has madethe capturing and

distribution of knowledgewidespread, and brought to the

forefront the issue of the management

of knowledgeassets

(Davenport 1997). The "knowledgemanagement"function

is spreading throughoutthe organisation, from marketing,

information management

systems and humanresources.

With knowledgenowbeing viewed as a significant asset

the creation and sharing of knowledge has become an

important factor within and betweenorganizations. Boisot

(1998) refers to the "paradox of value" whenconsidering

the nature of knowledge,in particular its intangibility and

inappropriateness as an asset and also the difficulty of

assessing and protecting its value (Priest 1994).

Copyright

©2001,A,~I. All rights reserved.

11e

FLAIRS-2001

facihtatesthe

I,°,ormat,onl

I .ow’

",ol

creation of m~

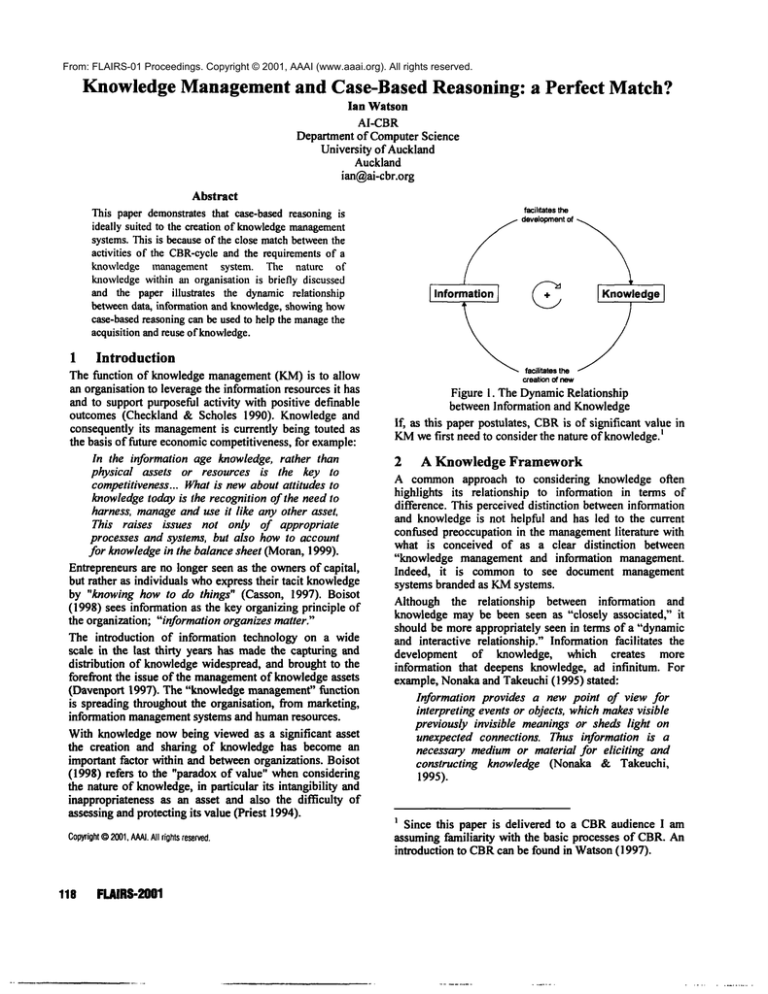

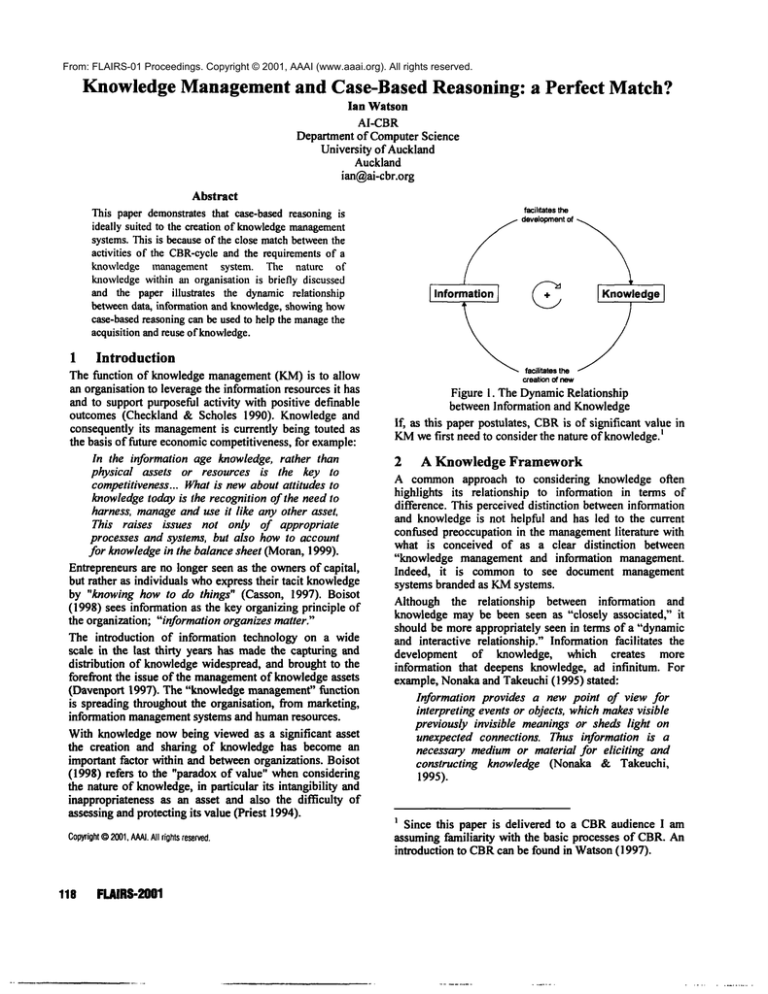

Figure 1. The DynamicRelationship

between Information and Knowledge

If, as this paper postulates, CBR

is of significant value in

KMwe first need to consider the nature of knowledge)

2

A Knowledge Framework

A commonapproach to considering knowledge oRen

highlights its relationship to information in terms of

difference. This perceiveddistinction betweeninformation

and knowledgeis not helpful and has led to the current

confused preoccupation in the management

literature with

what is conceived of as a clear distinction between

"knowledge managementand information management.

Indeed, it is commonto see document management

systems branded as KMsystems.

Although the relationship between information and

knowledgemaybe been seen as "closely associated," it

should be more appropriately seen in terms of a "dynamic

and interactive relationship." Informationfacilitates the

development of knowledge, which creates more

information that deepens knowledge, ad infinitum. For

example, Nonakaand Takeuchi(1995) stated:

Information provides a new point of view for

interpreting events or objects, whichmakesvisible

previously invisible meaningsor sheds light on

unexpected connections. Thus information is a

necessary mediumor material for eliciting and

constructing knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi,

1995).

Since this paper is delivered to a CBRaudience I am

assumingfamiliarity with the basic processes of CBR.An

introduction to CBRcan be found in Watson(1997).

fi

Perceptual

andconceptual

filters

...................................

p, !

:

p’,

Event

(experientialdatasource)

Agent

(tacit knowledae

source)

I

Information

Data

-~-

Feedback

.......................

J

Source:Adaptedfrom Boisot (1998)

Figure2. Data,InformationandKnowledge

(Boisot, 1998)

Whilst Polyani (1967) and Choo(1998) have viewed

dynamicinteractive relationship as part of the process of

knowingwhichfacilitates the capacity to act in context.

The dynamicnature of this relationship is illustrated below

in Figure1.

Similarly, to look at information purely in terms of the

degree to which it has been processed, i.e., the data,

information, knowledge hierarchy (Davenport 1997;

Checkland & Howell 1998) oversimplifies the complex

relationship betweenthe three intangibles. Stewart (1997)

notes:

The idea that knowledgecan be slotted into a datawisdomhierarchy is bogus, for the simple reason

that one man’s knowledge is another man’s data

(Stewart 1997).

The categories defined by Boisot and their interactions

maybe seen in Figure 2. It is important to note the

feedback element within this figure that illustrates the

dynamicand interactive relationship of information and

knowledgeas a positive feedbackloop.

Datais discriminationbetweenstates - black, white, heavy,

light, dark, etc. - that mayor maynot conveyinformation

to an agent. Whetherit does or not dependson the agents

prior stock of knowledge.For example,the states of nature

indicated by red, amberand green traffic lights maynot be

seen as informative to a bushmanof the Kalahari. Yet,

they mayperceivecertain patterns in the soil as indicative

of the presenceof lions nearby.

Thus, whereasdata can be characterised as a property of

things, knowledgeis a property of agents predisposing

themto act in particular circumstances.Informationis that

subset of the data residing in things that activates an agent

- it is filtered fromthe data by the agent’s perceptual or

conceptualapparatus (Boisot, 1998). This has a direct echo

in AlanNewell’sprinciple of rationality:

"If an agent has knowledgethat one of its actions

will lead to one of its goals, then the agent will

select that action" (Newell1982)

3

CBR is a methodology for KM

What then are the requirements of a KMsystem? At a

recent workshopheld at CambridgeUniversity a group of

people active in KMand AI identified the mainactivities

needed by a KMsystem (Watson 2000). These were

mapped to AI methods or techniques. The main KM

activities were identified as the: acquisition, analysis,

preservation and use of knowledge.This section will show

howCBRcan meet each of these requirements.

I argued in 1999 that CBRis not’an AI technology or

technique like logic programming,rule-based reasoning or

neural computing. Instead, CBRis a methodology for

problem solving (Watson 1999). Checkland & Scholes

(1990) define a methodologyas:

"...an organised set of principles which guide action in

trying to "manage" (in the broad sense) real-world

problem situations" (Checkland&Scholes 1990)

Nowconsider the classic definition of CBR:

".4 case-based reasoner solves problemsby using

or adapting solutions to old problems."(Reisbeck

& Schank 1989)

This definition tells us "what"a case-based reasoner does

and not "how"it does what it does. It is in Checkland’s

sense an organised set of principles. The set of CBR

principles are morefully defined as a cycle comprisingsix

activities 2 called the CBR-cycle

as shownin Figure 4.

2 Note that the original CBR-cycleof Aamodt& Plasa

(1994) comprisedonly four activities.

CASEBASEDREASONING 119

o

/-----7

i

new problem

i

~,~

J

’

?

i

/---7, REwsE

....... 7/’REwEw

/ /" e

new case

new solution

Figure 3. The CBR-cycle

This cycle comprisessix activities (the six-REs):

1. Retrieve similar cases to the problemdescription

2. Reusea solution suggestedby a similar case

3. Reviseor adapt that solution to better fit the new

problemif necessary

4. Reviewthe new problem-solution pair to see if

they are worthretaining as a newcase

5. Retainthe newsolution as indicated by step 4.

6. Refine the case-base index and feature weights as

necessary.

The six-REs of the CBRcycle can be mapped to the

activities required by a knowledgemanagementsystem.

Let us revisit Figure 2 and superimposethe steps of the

CBR-cycleupon it.

Nowwe can easily see that the event is the episodic data

that comprisesa case. The case is retained in a case-base

but typically undergoessomepre-processing and filtering

(indexing and feature weighting in CBRterminology). The

agent or the reasoner retrieves the case to solve some

problemand attempts to reuse it. This mayresult in some

revision or adaptation of the case’s solution resulting in a

newepisodic data and hence a newcase being created. The

newease is reviewed(involving comparingit against cases

already retained in the case-base) and if it is judgeduseful

retained. In addition, the use of the case (successfully or

otherwise) mayresult in the case-base’s indexing scheme

being or the feature weights refined. This completes the

knowledge management cycle indicated on Boisot’s

original diagram.

refine

Perceptual

andconceptual

filters

~

retention

Event

(experiential data source)

3ase-Base

retrieval~

Agent

(tacit knowledgesource)

Data

revision

reuse~

Figure 4. The CBR-cyclesupporting KnowledgeManagement

120

FLAIRS-2001

4 Multiple

Knowledge Sources

CBRsystems have traditionally been built around single

case-bases designed to solve a particular problem(Watson

1997). However, KMsystems may draw upon multiple

heterogeneous knowledgesources, just as you might use

several sources whenresearching a paper. Conventional

CBRsystems that use a proprietary case-base format

cannot integrate knowledgeresources and therefore may

not support a user with complex knowledgeneeds. Note

that creating multiple case-bases each searched by the

sameinterface is onlya partial solution to this problem.

Brown et al., (1995) proposed a solution whereby

knowledge could be drawn from multiple distributed

heterogeneous sources and temporarily held in "virtual

cases." This would still require someone(probably

knowledgeengineer) to design the structure of the virtual

cases in advance. The content of the virtual case-base

wouldbe obtained on demand.This is again only a partial

solution though it does have merit were real-time dynamic

data is usedin cases.

Dubitskyet al., (1999) describe the architecture of a CBRwarehousethat could contain multiple heterogeneouscasebases to solve this KMproblem.Their systemrelies on the

use of an ontology to overcomethe semantic differences

betweencase-bases. Thus, allowing a single CBRretrieval

systemto retrieve cases fromdifferent knowledgesources.

eGain3 (www.egain.com)have developed a product called

eGain KnowledgeGatewaythat provides seamless access

to multiple knowledgesources through a single interface

(eGain, 2001). This system uses a core CBRcomponent

retrieve solutions based upona conversational query from

a user. Knowledgecan be retrieved from Lotus Notes

databases, Microsoft Office documents, HTML

and PDF

files, e-mails as well as specifically authoredcase-bases.

5 Conclusion

CBRtherefore closely matchesKM’srequirements for the

acquisition (revision and retention), analysis (refinement),

preservation (retention) and use of knowledge(retrieval,

reuse and revision). Dubitskyet ai. (1999) refer to this

KM/CBR

synergy and it explains why CBRhas been used

successfully in manyKMsystems (Aha et al., 1999).

However,it is not a one-sided relationship. KMhas as

much to offer the success of CBRas vice versa. In

particular KMresearchers and practitioners have recognise

the importanceof organisational issues in the success of a

KMsystem and there is muchthat CBRpractitioners can

learn from the KMcommunity.

KMsystems are perhaps best viewedin a holistic systemthinking manner (Checkland & Howel, 1998) rather than

the morerestrictive technologyviewof a system. As such,

a KMsystem must support all activities that would

encourage a knowledgesharing culture within a learning

3 eGain have recently acquired Inference

pioneering CBRcompany

Corp. a

organisation. CBRonly provides methodological support

to someof those activities.

6

References

Aha, D., Becerra-Fernandez,I., Maurer, F. &MunozAvila, H. (1999). Exploring Synergies of Knowledge

Managementand Case-Based Reasoning. AAAITechnical

Report WS-99-10. ISBN1-57735-094-4

Aamodt,A. &Plaza, E. (1994). Case-BasedReasoning:

FoundationalIssues, MethodologicalVariations, and

SystemApproaches.AI Communications,7(i), pp. 39-59.

Boisot, M. (1998). Knowledge

Assets, Securing

Competitive Advantagein the Information Economy,

OxfordUniversity Press, Oxford, UK.

Brown,M., Watson,I. &Filer, N. (1995). Separating the

Cases from the Data; TowardsMoreFlexible Case-Based

Reasoning. In, Case-BasedReasoning Research and

DevelopmentVeloso, M., & Aamodt,A. (Eds.) Lecture

Notesin Artificial Intelligence 1010Springer-Verlag

Berlin.

Casson, M. (1997). Information and Organization, A New

Perspective on the Theoryof the Firm, ClarendonPress,

Oxford, UK.

Checkland,P. &Howel,S. (1998). Information, Systems

and InformationSystems, MakingSense of the Field, John

Wiley & Sons, UK.

Checkland,P. &Scholes, J. (1990). Soft Systems

Methodologyin Action. Wiley, UK.

Choo, C. W. (1998). The KnowingOrganization, Oxford

University Press, Oxford, UK.

Davenport,T. D. (1997). Information Ecology,Mastering

the Information and knowledgeEnvironment,Oxford

University Press, Oxford, UK

Dubitzky,W., Btichner, A.G. &Azuaje, F. J. Viewing

KnowledgeManagementas a Case-Based Reasoning

Application. In Exploring Synergies of Knowledge

Managementand Case-Based Reasoning David Aha, Irma

Becerra-Fernandez, Frank Maurer, and Hector MunozAvila, (Eds.) AAAIWorkshopTechnical Report WS-9910, pp.23-27. AAAIPress, MenloPark CA, US.

EGain(200 !). eGain KnowledgeGateway:rapidly access

unstructured

knowledge.

www’egain’c°m/d°esdpr°ducts/egain-kn°wled

ge-gateway

Pdf

Moran, N. (1999). Becominga KnowledgeBased

Organization, Financial TimesSurvey - Knowledge

Management, 28 th May1999, London, UK.

Newell, A. (1982). The Knowledge

Level. AI Vol. 18 pp.

87-127.

Nonaka,I. &Takeuchi, H. (1995). The KnowledgeCreating Company:HowJapanese CompaniesCreate the

Dynamicsof Innovation, OxfordUniversity Press, Oxford,

UK.

Polyani, M. (1967). The Tacit Dimension,Routledge

Kegan Paul, London, UK

CASEBASEDREASONING 121

Priest, W.C. (1994), AnInformationFramework

for the

Planning and Design of’Information Highways’,Berkley

InformationSite.

Riesbeck, C.K. &Schank, R. (1989). Inside Case-Based

Reasoning.Erlbaum,Northvale, N J, US.

Stewart,T.. A. (1997). Intellectual Capital, Nicholas

Brearly.

122

FLAIRS-2001

Watson,I. (1997). ApplyingCase-BasedReasoning:

techniques for enterprise systems. MorganKaufmann,San

Francisco, US.

Watson,I., (1999). CBRis a methodologynot

technology. In, the Knowledge

BasedSystemsJournal,

Vol. 12. no.5-6, Oct. 1999, pp.303-8. Elsevier, UK.

Watson,I. (2000). Report on Expert Systems

Workshop:Using AI to Enable KnowledgeManagement.

In, Expert UpdateVoi. 3 No. 2, pp. 36-38.