and the Outdoor Recreation 47#4.1111 Public Interest: Proceedings of the

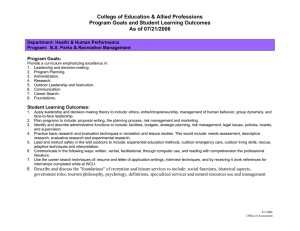

advertisement