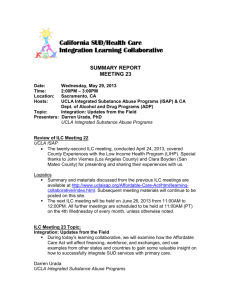

Partnerships between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Local Health Departments

advertisement