DETERMINING SURFACE TYPE FROM SURFACE NORMALS

advertisement

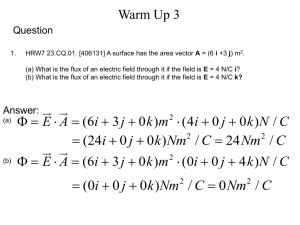

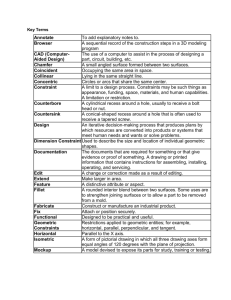

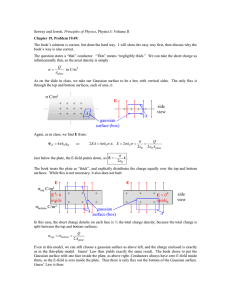

From: AAAI-82 Proceedings. Copyright ©1982, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved. DETERMINING SURFACE Paul Amaranth Academic Computer Services Oakland University Rochester, TYPE FROM SURFACE Intelli.gent Department and MI ABSTRACT By exploiting the relationship which exists between the Gaussian image and gradient space, can be utilized in the two representations conjunction to facilitate the interpretation of set of surface normals. The projection of the a can provide clear Gaussian image onto a plane quickly surface. I yield general knowledge is but only the binary image. This binary image a discreet version of the space we term the Unit Gradient Space (UGS). Analysis using the UGS quickly technique for provides a promising information about the surfaces acquiring basic under consideration. The ion recogni t i on [5] and segmentat ion [3] us i ng these however, the process of normals. In general, interpreting this local information to infer the underlying surface type is not well understood. Given a the question: This addresses paw collection of surface normals generated from a what can be determined single, smooth surface, variation of the about the surface? Using a for gradient space, we present an approach simple is purposely is to quickly the surface. surfaces. Our simple and limited obtain some basic If surface translated spatial normals image The and Gaussian is looks mode 1 observer centered. with the Y axis pointing projected The to the right. onto the image at pointing Space viewer entirely along up and scene is the Z axis the X axis orthogonally Z=l. image coordinate system defined, With the the system of coordinate we now consider the is closely The UGS spaces. gradient various and the gaussian space to gradient related If the equation for a smooth surface is sphere. then the observer directed of the form z=f (x,y), normals to that surface are Cp, q, -11 = C x/ 2, given by: y/ z, -11 eq. 1 (Fig. 1) Gradient space consists of the points [p,q] each of which represents a parti;ilar a surface orientation. The gaussian sphere Each point on its surface sphere of unit radius. the orientation of the plane tangent represents to the sphere at that point. The gaussian sphere space can be defined as tangent to the gradient Kender gradient space origin. c71 the at various illustrates the relationships among the very spaces I I Image I I I I ntroduct University Ml 48202 of There are many methods in low-level machine orientation vision which derive the 3-D surface coordinate point in an image. Optical at each texture gradient and flow Cl981, c71, [2,6] are all techniques used photometric stereo vectors. generate these surface norma 1 to for object have been suggested Methods distinguishing representation as our object knowledge of William Jaynes Systems Laboratory of Computer Science Wayne State Detroit, 48063 traces which the underlying NORMALS If clearly. the gaussian sphere and Representation information generated is from ignored and an image all are to a common origin, the gaussian image is formed [4,8]. This image can be seen as the locus of points formed by the intersection of the unit normals with a unit sphere called the Gaussian sphere. Any rotation in the scene causes a corresponding rotation of the Gaussian sphere about its origin. Histograming the X and Y components of the unit normals produces a 2-D approximation of the Gaussian image cal led the Gauss ian [3]. At the present histogram time, we do not utilize the cell counts of the histogram, Fig. 1. The ob server conica 1 and dir a ected CYl indric norma al sur S ace. of a the gradient space sys tern coord i nate conditions hold: 1) The gradient plane Z=-1 2) The the are embedded that such space is within the defined the scene following by intermediate genera consequently, p and q axes are aligned same units as the x and with and y axes sl / CP. IlCP9 q9 Pl = Discussion concerned with surfaces, not entire is The embedding gradient space, i nto space system. the = 0 eq. 3. 4 UGS for a right circular cone 1 / / (b’ + (b2 + l), 1) eq. 5, 6 given by 1 / (1 / q12> - 1 eq. 7 In real scenes, it is unlikely that objects wi 11 be so conveniently oriented. As consequence, the UGS represenation of either cone or a cylinder in some arbitrary orientation Y a a may describe a section of an ellipse. Consequently, the various surf aces not are distinquishable. Another possibility for standard orientation is suggested by the fol lowing observation. If a singly-curved surface is oriented such that a plane tangent to the surface is parallel to the image plane, the UGS curve of that surface will pass through the origin. The point on the curve at the origin corresponds to the rul ing on the surface determined by the tangent plane. Conversely, if the UGS curve of a singly-curved surface passes through the origin, then there exists a ruling on the surface with a tangent plane which is parallel to the image plane. Thus, a standard orientation can be defined as one in which some ruling of the surface is parallel to the image plane. For a cylinder, this equivalent to is setting the axis of the surface parallel to the image plane and results in a straight 1 ine Unit Gradient 1 I Space 2. in b = ; Fig. oneand, where b is the ratio of height to the radius of the base. These equations show that in the given orientation, conical and cylindrical surfaces give rise to straight line segments in the UGS. I ntui tively, it is easy to see that the projection of an arc of a sphere onto a plane perpendicular to the plane defined by that arc will result in a line segment. The UGS line for a cyl i nder will pass through the origin, while that of the cone cannot. Further, the ratio of the height to the radius of the base of a cone objects [5] and, at this point, we wil 1 narrow single our perspective to encompass only restriction, we will surfaces. As a further surfaces consider only conical and cylindrical cross section. We do this for with a circular two reasons. First, the form of their Gaussian images straightforward and easy to are great visualize. Cylinders lie along arcs of cones form arcs on lesser circles. circles and they are singly curved surfaces and Secondly, therefore representative of a class of surfaces Gradient :s Space , ql = b*sin(t) ql = We are the a [lo] 2 Pl IV sin(t), The curve is given by -1111 eq. in in Given a curve in the UGS, we want to know if we can determine whether it indicates a cylinder or a cone and what, if any,, parameters of the surface can be determined. First, let us assume that the axis of the cone or cyl inder generating the surface is parallel to the image plane. Since a rotation about the Z axis results in a corresponding rotation in the UGS, we can assume without loss of generality that the axis is parallel to the Y axis. It can be shown that a right circular cylinder results in points on a curve in the UGS given parametrically by be seen as an orthogonal projection of the same is a hemisphere onto the Z=-1 plane. Hence, it of gradient space and consists version bounded of the points = also result space UGS. between any of The center of the Gaussian sphere is at the origin number of interesting properties become then a current For the understandable. readi ly the most important result however, discussion, various the is that the rotational coupling of to figure 2. Refer obv i ous . becomes spaces Gradient space then corresponds to a central one hemisphere of the gaussian project ion of clearly sphere onto the Z=-1 plane. The UGS can q13 falling In particular, and singly-curved parameter the 3) CPl9 in complexity; planar surfaces. surface must curve in gradient 1 of the Gaussian sphere, and the unit gradient coordinate the scene 56 through a cone Thus we the origin will have of still a fast the UGS. The UGS curve for lie on an ellipse, however. method of distinguishing the symmetrical aligning the surfaces, projection surface the with ql this has y of the axis of the the axis effect of of the UGS. surfaces. cylindrical conical and At this point, is also surfaces are easily distinguished. It recover the ratio of height to the possible to angle at radius of the base in the form of the In this orientation, the apex of the cone. the in distance between the endpoints of the curve the UGS is a measure of the angle of the apex of the original conical solid. For a circular cone, this angle is equal to: In this standard orientation, equation 7 wi 11 not necessarily be valid. It is still possible to recover the ratio of height to the radius of the base, however, by exploiting the fact that symmetries in a surface are reflected symmetries in the Gaussian image. The center by of the arc in the Gaussian image will correspond to a ruling down the center of the cylinder or cone. The following procedure is based on this observation. 2 I acos( dist / 2 ) This yields only an approximate value, because of the digitization problem later. V method 8 however, mentioned Method VI The eq. standardizing the object to the observer consists of position relative two parts. The first part rotates the Gaussian image so that the center of the arc lies on the the center of the arc is at the Z axis; that is, origin of the UGS. This effectively rotates the the plane tangent to the surface so that approximate middle of the surface is parallel to the image plane. The second part performs a rotation about the Z axis so that the UGS curve For is symmetrical with respect to the ql axis. Resu 1 ts of analysis was generated by a Data for the parameters of an given program which, produced the normals for the visible object, surface. The surface normals were produced by analytically determining the orientation of each surface patches as sampled through a 30 of the space. A variety of image by 30 grid in the surfaces at various conical cylindrical and The .resulting manufactured. orientations were of normals were processed using the method sets described above. In all cases, the surfaces were standard brought either to, or very close to, a Figures 3 and 4 show typical orientation. -------------------------,----------------------*-0 I I A. i --------~---“---q--~---*-3--L--p--~*-~-- S--5--~-‘-,-SI B, Fig. 3. Gaussian histograms for a cylinder (a) an unstandardized pos i t ion and (b) the standard position. Fig. in 57 4. Gaussian histograms for a cone (a) an unstandardized position (b) the standard position. in and results for The cone. simi circular cylinder and a and between conical For apparent. are readily used to equation 8 was a circular differences cylindrical conical surfaces surfaces, determine illustrated the angle of in table the apex. As can 1. Results are be the seen, used of the surface. Table Apex angles circular cones using equation in to surf aces distinct aid in at traces different . This orientations fact could be [3]. segmentation Finally, there is much more which has yet to be exploited. Flatter yield a more condensed image in parameters of the elliptical curve reflect on the curvature of the surface. The counts in the cells of histogram concern the relative size of curvature of a surface. These are for further investigation. percent of computed values are within thirteen actual values calculated analytically. Note the values the robustness of the method; consistent starting the regard 1 ess of obtained are orientation lar result information surf aces the UGS. The in the UGS generating the Gaussian and/or rate all matters 1. calculated for various at different orientations, 8. All values in degrees. REFERENCES Cl1 Actual Angle Z Rotation X Rotation 53 Computed Angle 61 20 45 -45 2: 67 90 90 1; -45 0 0 0 110 110 127 127 viI 0 45 0 -20 -20 ;: :: Concluding Dl 59 76 76 96 96 :i Our of method of the adjusting 112 112 Remarks c41 Horn, B.K.P. representations A.I. Lab., M.I.T., c51 lkeuchi, using IJCAI-81 “Sequ i ns and Quillssurf ace topography. for A.I. Memo 536 (1979). K. “Recognition of the Extended Gaussian (19811, pp. 595-600. 3-D Image.” ” Objects Proc. C61 “Determining lkeuchi, K. Surface Orientations of Specular Surfaces by Using the Photometric Stereo Method.” IEEE Trans. m, 3 (1981). pp. 661-669. 171 Kender, J. Computer University, L81 standard initial it may in a Prazdny, K. From Map Cybernetics, c91 equivalent to the standard defined above. A variety of approaches were used to counter this difficulty, it has not been completely eliminated. This but the problem as does not appear to be a major orientation and ideal difference between the that obtained is only a few percent. “Shape from Science, Texture.” Dept. Carnegie-Mellon ~~~-~~-81-102 “Egomotion Optical 36 of (1981). and Relative Depth Biological Flow.” (1981) pp. 87-102. “Us i ng D.A. A. I. Lab., Smith, Images.” Enhanced M.I.T., A.I. Spherical Memo 530 (1979) [IO] Woodham, R.J. “Reflectance Analyzing Surface for Castings.” A. I. Lab., (1978) singly-curved When dealing with it may not be necessary for the input only one surface. Different types of R. “Three-Dimensional The Gaussian Image and Proc. PRIP-81 (1981). symmetrical in the the however, resulting quite m-328.- Dane, C. and Bajcsy, Segmentation Using Spatial Information.” resolution. the PP. c31 134 134 makes use of surfaces apparent nature Depend i ng on orientation. the surface, orientation of asymmetr i cal , appear somewhat that is not final orientation Coleman, E.N. and Jain, R. “Obtaining 3Shape of Textured and Specular Dimensional Surfaces Using Four Source Photometry.” Computer Graphics and Image Processing 18 (1982), The UGS image is formed by quantizing and [3] histograming the normals. As Dane and Bajcsy in 1 ies have pointed out, a major problem determine quantization effects. Resolution will whether a curve in the UGS is seen as a point, a smooth curve or as disjoint points. Dealing with allows the time, however, one surface at a possibility Clocksin, W.F. “Determining the Orientation Flow.” of Surfaces from Optical Proc. AISB/GI, Hamburg (1978), pp. 93-102. surfaces, to contain surfaces or 56 . Map Defects M. I .T., Techniques in Metal A I -TR-457