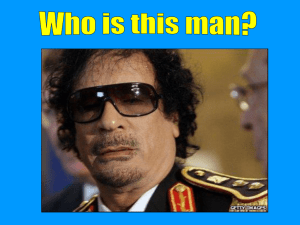

stalemate & siege THE LIBYAN REVOLUTION PART 3 October 2011

advertisement