Duplicate Laboratory Test Reduction Using a Clinical Decision Support Tool

advertisement

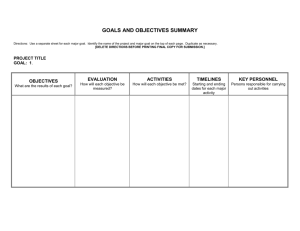

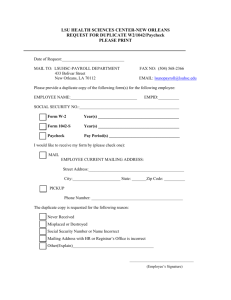

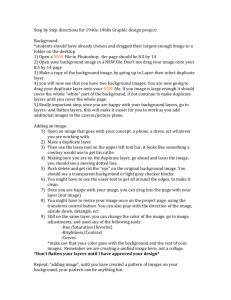

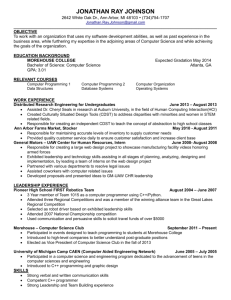

AJCP / Original Article Duplicate Laboratory Test Reduction Using a Clinical Decision Support Tool Gary W. Procop, MD,1 Lisa M. Yerian, MD,1,2 Robert Wyllie, MD,2 A. Marc Harrison, MD,3 and Kandice Kottke-Marchant, MD, PhD1 From the 1Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute and 2Medical Operations, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, and 3Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Am J Clin Pathol May 2014;141:718-723 DOI: 10.1309/AJCPOWHOIZBZ3FRW ABSTRACT Objectives: Duplicate laboratory tests that are unwarranted increase unnecessary phlebotomy, which contributes to iatrogenic anemia, decreased patient satisfaction, and increased health care costs. Materials and Methods: We employed a clinical decision support tool (CDST) to block unnecessary duplicate test orders during the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) process. We assessed laboratory cost savings after 2 years and searched for untoward patient events associated with this intervention. Results: This CDST blocked 11,790 unnecessary duplicate test orders in these 2 years, which resulted in a cost savings of $183,586. There were no untoward effects reported associated with this intervention. Conclusions: The movement to CPOE affords real-time interaction between the laboratory and the physician through CDSTs that signal duplicate orders. These interactions save health care dollars and should also increase patient satisfaction and well-being. 718 718 Am J Clin Pathol 2014;141:718-723 DOI: 10.1309/AJCPOWHOIZBZ3FRW Upon completion of this activity you will be able to: • outline ways that the use of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) can afford the opportunity to interact with clinicians at the time of order entry through clinical decision support tools (CDSTs). • describe how a CDST, such as the one used in this study, can avert thousands of unnecessary duplicate tests and save thousands of dollars without interruption of patient care. • list the various factors that can make an intervention of CPOE and CDSTs possible and sustainable. The ASCP is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The ASCP designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit ™ per article. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. This activity qualifies as an American Board of Pathology Maintenance of Certification Part II Self-Assessment Module. The authors of this article and the planning committee members and staff have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose. Questions appear on p 755. Exam is located at www.ascp.org/ajcpcme. A major initiative of the Obama administration is the continued deployment of electronic medical records throughout the health care system of the United States, and an important component is the demonstration of meaningful use. The institution of electronic medical records often has the accompanying benefit of computerized physician order entry (CPOE). In addition to decreasing transcription error that may occur when physician orders are translated and entered by unit clerks or other health care professionals, CPOE, in conjunction with clinical decision support tools (CDSTs), offers the opportunity to present real-time information to the provider that can alter decision making. It is clear that unnecessary and wasteful practices in medicine add cost to an already strained health care system.1-3 When a thorough retrospective review is undertaken, many © American Society for Clinical Pathology Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 28, 2016 CME/SAM Key Words: Test utilization; Clinical decision support; Meaningful use AJCP / Original Article Material and Methods CDST The Cleveland Clinic uses Epic (Epic, Verona, WI) as the hospital information system and Sunquest (Sunquest, Tucson, AZ) as the laboratory information system. The CDST that was designed consisted of an immediate electronic notification alert that a same-day duplicate test was being ordered (ie, a pop-up box) ❚Image 1❚. In addition, the alert was configured to display the most recent result for the order that was being attempted, if available. This latter feature has been particularly appreciated by the users. This CDST had to be evaluated extensively in the test environment prior to implementation. Challenges © American Society for Clinical Pathology ❚Image 1❚ The hard stop clinical decision support tool (CDST) informs the provider that the test being ordered is a duplicate that is not usually warranted more than once per day. It also provides the most recent result for this test. A nonelectronic means to override this test is provided, but it will necessitate a telephone call to Client Services. Note: This is a mock-up of the hard stop CDST; the patient and physician information is construed and does not represent actual individuals. encountered during testing included dealing with a single duplicate test when multiple tests were ordered simultaneously (ie, the duplicate test was within an order set) and standardizing the use of exclusion codes used by laboratory processing personnel, so that when duplicate tests were necessary because of broken tubes or other specimen collection/transport issues, the CDST tool would not be activated (ie, a duplicate would be appropriate in those instances). Notification, Feedback, and Implementation This study was reviewed by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. The program was introduced to the medical staff following approval from Medical Operations and the institutional leadership. It was introduced via a common home page used by all physicians at our institution. The initial phase of the rollout consisted of a pilot of 13 tests. Feedback was sought from the entire medical staff concerning the project and the tests for which the CDST would be used prior to initiation. Feedback was used to modify the test list by one test due to valid practice differences that were not considered initially. The second phase of implementation consisted of adding 77 tests to the activation list. The final phase consisted of implementing the CDST on the remaining tests in the entire orderable test menu for which it was deemed medically appropriate. This list was too extensive to vet with the entire medical staff, so it was reviewed by all physician members of the Test Utilization Committee and the most conservative consensus was used. The final hard stop list consisted of 1,259 tests that would not be allowed more than once per day. 719 Am J Clin Pathol 2014;141:718-723 DOI: 10.1309/AJCPOWHOIZBZ3FRW 719 719 Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 28, 2016 laboratory tests performed during a patient care episode may be unnecessary. Thereby, the value and associated cost of the test in the diagnostic or management process may be determined. Duplicate testing, although valid in some instances, is often unnecessary. This, in our experience, is often performed because the second ordering physician is unaware of the existing order. Duplicate laboratory tests have several potential untoward affects. These include pain associated with the additional phlebotomies; the contribution toward iatrogenic anemia, which in turn affects wound healing and infection; and increased health care costs accrued through specimen collection, transport, testing, resulting, and the clinical response to the result.4,5 Finally, tests with less than 100% specificity all have a false-positive rate. False-positive test results must be addressed and may lead to unnecessary additional testing, which have further implications with respect to patient safety and increased health care costs. The Cleveland Clinic has fully implemented CPOE. Therefore, we examined the possibility of using a CDST to alert the ordering physician of duplicate test orders. The earliest form of this CDST that we tried allowed the physician to bypass the alert and continue to place the duplicate order, if he or she desired (ie, a soft stop). Two pilot projects were performed that examined this type of CDST intervention (data not shown). It proved effective in decreasing redundant orders for expensive molecular diagnostics tests that were ordered by specialists on select patient populations (eg, quantitative cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus polymerase chain reaction [PCR] in transplant recipients). However, it proved ineffective for stopping duplicate test orders for routine assays (eg, Clostridium difficile PCR). The Test Utilization Committee of the Cleveland Clinic, therefore, proposed to the medical leadership of the institution to change the CDST so that unnecessary duplicate test orders would be completely blocked for select tests (ie, a hard stop). The impact of this intervention with respect to financial savings was monitored for 2 years. We also reviewed patient safety records for the first year following implementation. Procop et al / Duplicate Laboratory Test Reduction Using CDST A method was devised to allow for a physician to bypass the blocked duplicate order and still place the order, if he or she felt strongly that a duplicate test was necessary. This was done to ensure that this intervention could in no way interfere with patient care. The clinicians who wanted to override the hard stop were required to call our Client Services area and provide their name, the duplicate order request, and the reason they needed the duplicate test. These interactions were recorded and a monthly report was generated. Results In total, 11,790 unnecessary duplicate orders were blocked by the hard stop CDST in 2 years of activity (2011 and 2012). Of the 12,204 times that this CDST alerted, the clinician called to request that the duplicate test still be performed only 414 times (3%). A cost avoidance analysis of the impact of this revealed a savings of $183,586, which included materials and labor for laboratory personnel ❚Table 1❚, ❚Figure 1❚, and ❚Figure 2❚. ❚Table 1❚ Hard Stop Alert for Laboratory Ordersa Year/ Month Initial Total AttemptsAttempts Actual Mean to Order to Order Total Technical Supply Cost Laboratory Laboratory Reduction Cost per Monthly AccumuLabora- Labora- Technical Labor Cost, Savings, Order Orders in Cost Laboratory Cost lated Cost tory Test tory Test Time, min Cost, $ $ $ Permitted Prevented Savings, $ Test, $ Savings, $ Savings, $ 2011 January 237 416 1,181 567 1,990 2,557 10 227 –108 10.79 2,449 2,449 February 217 401 1,362 654 2,776 3,429 14 203 –221 15.80 3,208 5,657 March 196 307 1,312 630 2,228 2,857 4 192 –58 14.58 2,799 8,456 April 148 243 1,011 485 2,008 2,494 5 143 –84 16.85 2,409 10,865 May 543 1,105 3,301 1,584 6,427 8,012 25 518 –369 14.75 7,643 18,508 June 589 986 3,994 1,917 8,544 10,461 12 577 –213 17.76 10,248 28,757 578 991 4,063 1,950 5,109 7,060 12 566 –147 12.21 6,913 35,670 July August 659 1,251 5,068 2,433 9,287 11,720 16 643 –285 17.78 11,435 47,105 1,006 3,830 1,838 6,681 8,519 20 552 –298 14.89 8,221 55,326 September 572 October 552 986 4,301 2,064 4,810 6,875 19 533 –237 12.45 6,638 61,964 November 577 973 4,128 1,981 5,926 7,908 16 561 –219 13.70 7,688 69,652 December 642 1,137 4,888 2,346 15,601 17,947 17 625 –475 27.95 17,472 87,124 2012 January 594 1,009 4,162 1,998 5,480 7,517 20 574 –253 12.66 7,264 94,388 February 532 958 3,612 1,734 6,009 7,751 21 511 –306 14.57 7,445 101,834 March 539 992 4,265 2,047 5,981 8,032 20 519 –298 14.90 7,734 109,567 720 938 5,409 2,596 9,114 11,717 18 702 –293 16.27 11,424 120,991 April May 689 850 5,100 2,448 7,587 10,083 14 675 –205 14.63 9,878 130,870 June 594 1,053 4,274 2,052 6,361 8,429 24 570 –341 14.19 8,088 138,958 545 914 3,391 1,628 6,819 8,621 23 522 –364 15.82 8,257 147,215 July August 553 952 3,204 1,538 6,636 8,218 23 530 –342 14.86 7,876 155,091 September 458 816 2,896 1,390 4,901 6,360 10 448 –139 13.89 6,221 161,312 October 419 690 2,714 1,303 5,329 6,811 19 400 –309 16.25 6,502 167,814 November 487 924 3,056 1,467 5,880 7,389 21 466 –319 15.17 7,070 174,885 December 564 1,074 3,422 1,643 7,540 9,208 31 533 –506 16.33 8,701 183,586 183,586 Total 12,20420,97283,944 40,293149,025 189,973 414 11,790b a The table demonstrates 2 years of data. The number of initial duplicate order attempts per month is listed. In addition, the total number of attempts to order duplicate tests is listed; the great difference between the total attempts to order duplicate tests and the initial attempt suggests the physician is not reading the alert, which supports the notion of clinical decision support tool fatigue (ie, pop-up fatigue). The number of duplicate laboratory tests that were permitted is listed, and the difference between this and the initial duplicate order attempts represents the actual laboratory orders permitted. The mean cost per laboratory test avoided, the monthly cost savings, and the accumulated cost savings are given, as well as the totals. b Total laboratory orders prevented: 2011, n = 5,340; and 2012, n = 6,450. 720 720 Am J Clin Pathol 2014;141:718-723 DOI: 10.1309/AJCPOWHOIZBZ3FRW © American Society for Clinical Pathology Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 28, 2016 Monitoring The number of times the hard stop CDST was activated and the types of tests for which it was activated were recorded each month. The internal laboratory costing and timing data, known for each laboratory test, were used to calculate the cost avoidance to the system for not performing these unnecessary duplicate orders; this included materials and labor. We did not capture cost savings associated with decreased phlebotomy or specimen collection by other health care providers, specimen transport, specimen accessioning, specimen processing, or the time needed for the health care provider to review and possibly act on the test results. Therefore, although we believe the laboratory cost avoidance data to be accurate, there was likely a larger cost avoidance to the system that was more difficult to quantify. We monitored activity for untoward complications. One author (G.W.P.) was the contact for any complaints. In addition, the Cleveland Clinic uses the Safety Event Reporting System (SERS) to archive and report untoward events and injuries. We reviewed the SERS database for the first year following implementation to determine if there were any untoward events or patient safety concerns associated with this project. AJCP / Original Article There has been support of this initiative from the medical staff. During the final phase of implementation, there were only two instances when clinicians reported that they felt the CDST was inappropriate for a particular test. Those complaints were deemed valid, and the tests in question were removed from the hard stop test list. The retrospective review of the SERS database for the first year following implementation demonstrated that there were no untoward events or patient safety concerns associated with this project. Discussion The annual cost of health care in the United States has consistently exceeded the annual growth of the gross domestic product since 1965.6 Costs continue to grow at an Initial attempt to order lab test Total attempts to order lab test Lab orders permitted Actual lab orders prevented 1,400 1,200 1,000 600 400 200 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 2011 2012 ❚Figure 1❚ The total number of times the hard stop alert fired (blue line), the number of times it initially fired (red line), and the number of override requests made to Client Services (purple line). The number of actual duplicate tests averted (green line) is the difference between the number of initial alerts (red line) and the override requests (purple line). The great difference between the initial firing of the alert and the total attempts made for a particular test (blue line) suggests the physician is not reading the alert, which supports the notion of clinical decision support tool fatigue (ie, pop-up fatigue). $250,000 Accumulated cost savings Monthly cost savings $200,000 $150,000 $100,000 $50,000 $0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 ❚Figure 2❚ Monthly and cumulative cost savings achieved using this automated clinical decision support tool. © American Society for Clinical Pathology 721 Am J Clin Pathol 2014;141:718-723 DOI: 10.1309/AJCPOWHOIZBZ3FRW 721 721 Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 28, 2016 800 Procop et al / Duplicate Laboratory Test Reduction Using CDST 722 722 Am J Clin Pathol 2014;141:718-723 DOI: 10.1309/AJCPOWHOIZBZ3FRW since intervention in the laboratory would not help avert unnecessary phlebotomy and its sequelae or save on specimen collection/transport costs. We first studied the effects of an electronic notification of the presence of a duplicate test order as a means to reduce unnecessary testing. These pilot projects demonstrated that if the provider were given the option of continuing with an inappropriate duplicate order, this would occur often, particularly for a routine test. In addition, a detailed analysis of order entry patterns during the implementation of the hard stop CDST showed that in many instances, providers would try multiple times to place the same duplicate order without calling Client Services, which suggested that they were not reading the alert. Electronic order entry and the electronic medical record represent significant advances in medical care. However, systems that do not clearly show pending orders may be associated with ordering patterns that are excessive and costly. Electronic notification of duplicate orders through a CDST, as we have described, is possible in some of these systems. Our findings suggest that a substantial number of unnecessary, redundant orders may be blocked with such a CDST and that significant health care costs may be saved with no untoward effects on patient care. This project resulted in the avoidance of 11,790 unnecessary same-day duplicate orders within 2 years, which resulted in a cost avoidance of $183,586. There were no SERS events or significant complaints associated with this project. We believe this initiative was successful for several reasons. Foremost, the Test Utilization Committee has broad representation from multiple disciplines. All members are focused on best practice and optimal test algorithms for patient care and not on cost reduction. The recommendations from this group were thereafter discussed with senior medical leadership, so as to pilot a systemwide change. Support of medical leadership was essential, as was found by Kim et al.1 The partnership with leaders and technical experts in informatics to design, test, and implement the suggested interventions was the next most important step. The thorough assessment of the CDST in the test environment was critical to discover anomalies prior to a true rollout, since these anomalies, when present in the clinical environment, frustrate users and diminish support for the project. These assessments also uncovered inefficiencies in the clinical laboratory that required attention prior to implementation. The solicitation of feedback from the medical staff, as well as the ability to remove tests from the hard stop list in a prompt manner, was also useful for initial and continued support for this project. The collegial and nonconfrontational interactions when requests were made to remove a test from the hard stop list maintained good working relationships between this team and the medical staff. The cost savings associated with © American Society for Clinical Pathology Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 28, 2016 alarming rate, with the implementation of new and expensive diagnostics and interventions. Although many of these tests and procedures are lifesaving, it has been estimated that more than $6 billion of the annual expenses for medical care in the United States are spent on tests and/or procedures that are unnecessary.7 Many studies have demonstrated great variation of the use of laboratory testing between different health care providers for similar diseases, which suggests there is waste in the system.8-12 More important than the impact of unnecessary tests and procedures on financial considerations, in some instances, these may result in patient harm.7 A review of this literature demonstrates not only the serious need to control unnecessary testing but also the need for evidence-based best practices for the appropriate use of these diagnostic tools. The Test Utilization Committee at the Cleveland Clinic is a multidisciplinary task force that reports to and is supported by institutional leadership. This structure affords the opportunity for participation from all interested staff members from all departments, which ensures the engagement of participants. The activities of the committee are approved by institutional leadership, and the results of interventions are monitored and reports are provided, which is similar to other models that have been demonstrably effective.1,13 Kim et al1 provide an excellent review of their 10-year test utilization experience in a major urban academic medical center, wherein similar and other tools were employed. Through these active interventions and support from institutional leadership, their group was able to save millions of dollars in blood components and reduce the amount of inpatient testing by 26%. Their approach and ours provide opportunities for input and communication from end users, as well as obtaining support and guidance from institutional leadership. An evaluation of the causes of unnecessary, same-day duplicate orders by our Test Utilization Committee disclosed that duplications occur for a variety of reasons. One important reason was that some caregivers considered themselves too busy to review the pending order list for each patient. Admittedly, navigation from the routinely used ordering screen to check for pending orders does take additional steps. These providers also informed us that they were more likely to simply place the orders they needed, with the supposition that the laboratory would find and ameliorate duplicate requests. Although laboratory technologists may occasionally intercept duplicate test orders, using them to detect and eliminate redundant tests would be a gross misappropriation of these valuable human resources. Therefore, given this understanding, and knowing that it has been estimated that physicians control as much as 80% of the cost in the health care system, we decided to use a CDST in conjunction with CPOE to intervene directly with the physician in a reasonable way to control cost.14 In addition, we wanted to intervene before the specimen was collected, AJCP / Original Article Address reprint requests to Dr Procop: Dept of Molecular Pathology, 9500 Euclid Ave, LL2-2, Cleveland, OH 44195; procopg@ccf.org. This publication was supported through a cooperative agreement with the Cleveland Clinic with funds provided in part by federal funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services; and Division of Laboratory Science and Standards under cooperative agreement U47CI000831. The findings in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We thank the members of the Test Utilization and Medical Operations Committees for their support and ever-innovative ideas and the members of the Clinical Systems office team for operationalizing these ideas. Special thanks to Shirley Stahl and Donna Adams for programming and informatics efforts and to Rob Tuttle for the financial analyses. © American Society for Clinical Pathology References 1. Kim JY, Dzik WH, Dighe AS, et al. Utilization management in a large urban academic medical center: a 10-year experience. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:108-118. 2. Robinson A. Rationale for cost-effective laboratory medicine. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:185-199. 3. Benson ES. Initiatives toward effective decision making and laboratory use. Hum Pathol. 1980;11:440-448. 4. Lyon AW, Chin AC, Slotsve GA, et al. Simulation of repetitive diagnostic blood loss and onset of iatrogenic anemia in critical care patients with a mathematical model. Comput Biol Med. 2013;43:84-90. 5. Tosiri P, Kanitsap N, Kanitsap A. Approximate iatrogenic blood loss in medical intensive care patients and the causes of anemia. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(suppl 7):S271-S276. 6. Sisko A, Truffer C, Smith S, et al. Health spending projections through 2018: recession effects add uncertainty to the outlook. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28: w346-w357. 7. Good Stewardship Working Group. The “top 5” lists in primary care: meeting the responsibility of professionalism. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1385-1390. 8. Daniels M, Schroeder SA. Variation among physicians in use of laboratory tests, II: relation to clinical productivity and outcomes of care. Med Care. 1977;15:482-487. 9. Bell DD, Ostryzniuk T, Verhoff B, et al. Postoperative laboratory and imaging investigations in intensive care units following coronary artery bypass grafting: a comparison of two Canadian hospitals. Can J Cardiol. 1998;14:379-384. 10. Smith AD, Shenkin A, Dryburgh FJ, et al. Emergency biochemistry services—are they abused? Ann Clin Biochem. 1982;19(pt 5):325-328. 11. Powell EC, Hampers LC. Physician variation in test ordering in the management of gastroenteritis in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:978-983. 12. Ashton CM, Petersen NJ, Souchek J, et al. Geographic variations in utilization rates in Veterans Affairs hospitals and clinics. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:32-39. 13. Lewandrowski K. Managing utilization of new diagnostic tests. Clin Leadersh Manag Rev. 2003;17:318-324. 14. Berndtson K. Managers and physicians come head to head over cost control. Healthc Financ Manage. 1986;40:23-24, 28-29. 723 Am J Clin Pathol 2014;141:718-723 DOI: 10.1309/AJCPOWHOIZBZ3FRW 723 723 Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 28, 2016 this project is the most easily measured metric, in contrast to anemia and patient satisfaction, which are determined by many factors. Although it is more difficult to quantify the amount of blood not drawn and the patient satisfaction associated with fewer phlebotomies, we believe these are important benefits of this initiative. Finally, the indirect measures of safety, as evidenced by a lack of complaints concerning these interventions and the review of SERS events that showed no events related to this intervention, support that this intervention was safe as well as effective. The appropriate use of clinical laboratory tests remains the concern of all health care providers. The resources spent on unnecessary testing could be better used throughout the system, such as for better care of patients with chronic diseases. The initiative described represents a consensus-based approach to the limitation of unnecessary, same-day duplicate test orders that may be employed elsewhere, particularly in hospitals using the same information system. The automated nature of the system requires minimal maintenance and provides automated and consistent interventions. We encourage the formation of multidisciplinary test utilization committees in hospitals and health care systems where they do not exist.