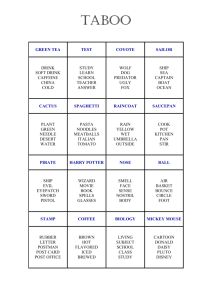

option. [Schelling] A taboo is a particularly forceful type... refers to danger, and it involves expectations of awful or... Tannenwald, “Stigmatizing the Bomb: Origins of the Nuclear Taboo,” 29(4)

![option. [Schelling] A taboo is a particularly forceful type... refers to danger, and it involves expectations of awful or... Tannenwald, “Stigmatizing the Bomb: Origins of the Nuclear Taboo,” 29(4)](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/013668600_1-4fd7d3b44e58bd958e9d6a767f11f3f0-768x994.png)

Tannenwald, “Stigmatizing the Bomb: Origins of the Nuclear Taboo,” 29(4)

International Security (2005): 5-49.

Nuclear Taboo – normative belief that the first use of nukes is an “unthinkable” policy option. [Schelling] A taboo is a particularly forceful type of norm – “it is a prohibition, it refers to danger, and it involves expectations of awful or uncertain consequences or sanctions if violated.” (9) Nuclear taboo is a de facto , not a legal, norm.

Argument

Tannenwald argues that this taboo has constrained use of nukes since 1945 by reinforcing deterrence (embedding deterrence within a set of shared practices, institutions, and expectations) and inducing restraint in the absence of deterrence. It also served as a crucial instrument in deterring proliferation.

Tannenwald’s argument focuses on the factors explaining the evolution of this taboo. She argues that “[a]lthough rationalist variables are important, the taboo cannot be explained simply as the straightforward result of rational adaptation to strategic circumstances.” (7) This is because:

Rise of taboo has not been a simple function of interests of nuke states, and in fact developed in face of official resistance by the U.S. and other states.

Evolution of taboo has a normative/moral dimension shaped by competition of two approaches to the interpretation of nukes: o

Military argument that technology is value-neutral – moral nature depends on use of weapon. o

Argument that any use is prohibited because nukes themselves are proscribed. The line between conventional and nuclear weapons had to be created.

Tannenwald draws on a constructivist approach to demonstrate how this international norm developed and become implemented domestically through processes of instrumental adaptation and strategic bargaining, moral consciousness raising, institutionalization and habitualization.

Evidence

Process tracing and discourse analysis of primary and secondary sources.

History of the taboo

A.

Emergence (1945-1962)

•

First developed in 1950s as a result of operational policies and categories that established nuclear weapons as different from other kinds of weapons.

(Truman policy – refused to let military have custody of the nukes; UN definition of category of WMD; Soviet Union regularly proposed prohibition on their use in 40s and 50s as step towards disarmament).

• Grassroots movement in Western Europe, U.S. and Japan. Antinuke movement led to shift in U.S. public opinion on nukes prior to change in leaders’ opinions. Movement contributed to creation of taboo by expanding discourse on nukes to non-security issues, by engaging in moral consciousness-raising, and by mobilizing public support.

• As the taboo emerged, the Eisenhower administration sought to resist it and to promote a competing norm of selective use of nuclear weapons

(process of strategic social construction of norm that tactical nukes should be treated as ordinary weapons)

• By 1957 Eisenhower administration had instrumentally adapted to pressures of the antinuclear movement and public opinion, though did not share the emerging taboo.

• U.S., Soviet Union and UK adopted testing moratorium (1958) and atmospheric test ban (1963) in response to mobilized public opinion.

B.

Institutionalization and internalization

• Institutionalization of taboo in multilateral agreements, U.S.-Soviet bilateral arms control agreements, and U.S. policy made possible by widespread acceptance that nukes should be for deterrence and not use

[Examples include JFK administration (1961) seeking to reduce reliance on nukes and develop more flexible and conventional alternatives; ABM

Treaty with Soviet Union ((1972) essentially a ‘no strategic first use’ treaty); nuke states extended negative security assurances to nonnuke states (1978)].

• Factors contributing to institutionalization: strategic superpower stalemate reinforced nuclear role of deterrence, not use; emergence of nonalignedcountry majority in UN General Assembly; democratization of nuke policy process in the U.S.; strong personal objections of administration officials [Sec of Defense Robert McNamara and Sec of State Dean Rusk].

• Revival of the nonnuclear movement in 1980s – challenged deterrence itself. Protests helped bring Reagan administration back to arms control table, which it had previously repudiated.

Alternative Explanations/Critiques

Realist view – story of taboo is one of self-interest and prudence. Sagan’s interpretation that it constitutes a ‘tradition of nonuse’ and not a taboo, b/c best explained by prudential and not normative considerations.

1

Rationalist view – rationality of having a social convention on non-use of nukes

(due to uniquely destructive nature and impossibility of defense). Taboo is selfenforcing and easier to monitor and enforce b/c it operates within small (rather than large) group of nuke states. Tannenwald does not disagree, but argues that actors have attached a normative – and not simply rational/prudent – dimension to the taboo, and few policymakers have viewed it as self-enforcing.

1

Sagan distinguishes between a tradition – easily disrupted by a violation – and a taboo – which is more robust. But it is not clear that all violations would necessarily disrupt the nuclear taboo, i.e. if used in a terrorist attack, by a rogue state etc. A hard case would be a deliberately ‘rational’ use by a major nuke power, and disruption of the taboo would depend on circumstances and response of the international community. Tannenwald views the nuclear taboo as a prohibitive norm – that do not render violations impossible, but make them unlikely by raising “threshold of what counts as a legitimate exception to the rule.” (40)