Climate Adaptation Planning for Homeless Services and Other District Services Kevin Partowazam

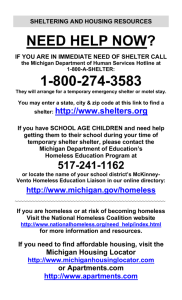

advertisement

Climate Adaptation Planning for Homeless Services and Other District Services Kevin Partowazam Table of Contents Partowazam 1 I. Purpose ................................................................................................................................................. 2 II. Scope ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. Background on Homelessness ................................................................................................... 5 IV. Background on Climate Change Adaptation Planning ....................................................... 8 V. Background on DC Homeless Services .................................................................................... 12 VI. Climate Change Projections....................................................................................................... 15 VII. Climate Change Adaptation Recommendations for DC Homeless Services ............ 18 Recommendation 1: As a matter of policy, conduct a summer PIT survey ........................... 19 Recommendation 2: As a matter of policy, develop an annual summer shelter plan ....... 20 Recommendation 3: As a matter of policy, implement existing summer right to shelter requirements .................................................................................................................................................. 20 VIII. Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 21 I. Purpose Partowazam 2 The following report aims to fill a gap in the District of Columbia’s climate change adaptation planning efforts by identifying, analyzing, and recommending how the District of Columbia can develop climate adaptation plans for specific city services. This effort is the result of initial consultation with District Department of the Environment (DDOE) staff, in which staff indicated efforts were already underway for a District-wide climate change adaptation plan, which is meant to analyze climate change impacts, assess the District’s vulnerabilities to climate change, and propose adaptation plans to make the District more resilient to climate change impacts. 1 Given that this high-level work is already underway, this project is intended to demonstrate the next level of climate change adaptation planning, in which the District would begin to consider how its individual Agencies, and the services that provide, could begin preparing for the impacts of climate change based on the impacts, vulnerabilities, and strategies that are to be identified in the District-wide adaptation plan. While one could choose to focus on any District of Columbia Agency or city service, this report focuses on the District’s homelessness services. This particular service was chosen for two reasons, one being an observed gap in planning efforts, and the other being the high-profile challenges that this service already faces in its daily, seasonal, and annual operations. The observed gap in planning efforts originates in an initial review of 2012 Sustainable DC Plan 2, which has Climate and Environment Goals focused on adaptation and preparedness, with efforts led by DDOE for energy infrastructure planning, DC’s Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency (HSEMA) for emergency service planning, DC’s Office of Planning (OP) 1 "Request for Applications - Climate Adaptation Planning." District Department of the Environment, 9 Aug. 2013. Web. <http%3A%2F%2Fddoe.dc.gov%2Fnode%2F624992>. 2 "Sustainable DC Plan." Sustainable DC, 2012. Web. <http://www.sustainabledc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/SDC-FinalPlan_0.pdf>. Partowazam 3 for development planning, and the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) for transportation infrastructure planning. While these are excellent and necessary efforts, the only service-focused planning effort is limited to HSEMA’s emergency planning efforts and does not appear to include partner agencies (these are identified as the Metropolitan Police Department, District of Columbia Fire Department, DDOE, and OP) that administer aid to key populations, like the homeless, that are uniquely vulnerable to emergencies caused by weather extremes (e.g., extreme heat, storms, and flooding). The high-profile challenges of the District’s homelessness services are seen regularly in local media, and have spanned multiple mayoral administrations, including the Fenty Administration 3, the Gray Administration 4, and the Bowser Administration 5. Specific criticisms and concerns with District’s homelessness services typically focus on the sheer volume of need, the living conditions at the District’s main shelter located at DC General, and seasonal winter housing of families and individuals in motels due to overcrowding at existing shelters. These concerns have prompted the recently elected Bowser Administration to propose an increase in sales tax to support homelessness services and a plan for new local shelters. 6 These proposals are important, and underscore the high profile of the District’s homelessness challenges. 3 Jouvenal, Justin, Robert Samuels, and DeNeed L. Brown. "D.C. Family Homeless Shelter Beset by Dysfunction, Decay." Washington Post. The Washington Post, 12 July 2014. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-family-homeless-shelter-besetby-dysfunction-decay/2014/07/12/3bbb7f50-f739-11e3-a3a5-42be35962a52_story.html>. 4 Davis, Aaron C. "Judge Issues Restraining Order, Forcing D.C. to Provide Safer Housing for Homeless Families." Washington Post. The Washington Post, 7 Mar. 2014. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-politics/judge-issues-restraining-orderforcing-dc-to-provide-safer-housing-for-homeless-families/2014/03/07/e1879716-a653-11e3-9cff-b1406de784f0_story.html>. 5 Davis, Aaron C., and Mike DeBonis. "In 11th-hour Move, D.C. Finds More Hotel Rooms for Homeless Families." Washington Post. The Washington Post, 6 Feb. 2015. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-politics/dc-files-emergency-motion-toallow-homeless-placements-in-makeshift-shelters/2015/02/06/3aea1848-adf5-11e4-ad71-7b9eba0f87d6_story.html>. 6 Davis, Aaron C. "D.C. Mayor Proposes Tax Increases to Confront Homeless Crisis, Metro Woes." D.C. Mayor Proposes Tax Increases to Confront Homeless Crisis, Metro Woes. The Washington Post, 2 Apr. 2015. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-politics/dc-mayor-proposes-tax-increase-to-confront-homeless-crisis-metrowoes/2015/04/02/eab91c10-d730-11e4-ba28-f2a685dc7f89_story.html>. II. Scope Partowazam 4 Given the potentially broad range of items that may be included in a climate change adaptation plan for homeless services, this report aims to have a very narrow focus for the sake of clarity for the reader, feasibility for potential implementation, and the practical constraints of what can be effectively achieved in a single report. The causes of homelessness are complex, as are the unique causes in the District of Columbia. While these items will be discussed for background purposes, this report does not aim to propose to solve these issues, or do away with homelessness altogether. Rather, this report will focus on observed and projected trends, and consider how climate change impacts may factor into policy and planning decisions, with the assumption that homelessness will continue to exist in some capacity. In terms of climate change projections and planning scenarios, this report will rely on broad, high-level trends. While many tools for analyzing climate change impacts and downscaling models to the local level exist, these efforts will be addressed in the District of Columbia’s existing climate change adaptation efforts. Thus, climate projections used in this report will focus more on generalized impacts, and use range projections where appropriate. Using a highlevel approach will make it easier to adjust and revise the approach taken in this report based on the specific scenarios DDOE identifies in its District-wide climate change adaptation plan. It is expected that any District Agency that embarks on developing its own plan will be informed by DDOE’s efforts, if not directly assisted and guided by DDOE itself. Overall, the approach taken in this report is meant to be adaptable to any District Agency or city service. While it focuses on homelessness, its intended that other services (e.g., sanitation services, public health services, etc.), may turn to this report as a case study when developing their own climate change adaption plans. Often, agencies without a clear and explicit Partowazam 5 environmental mission may hesitate or struggle to identify how their mission and services are impacted by the environment and climate change. It is hoped that by stepping through the approach taken in this report, it will become clear that all agencies can identify that they will indeed be impacted by climate change, and that they have the means to address those impacts in their planning and polices moving forward. III. Background on Homelessness Establishing baseline context and looking at recent trends in homelessness across the U.S. and in the District of Columbia is important for understanding the existing state of the District’s challenges with homelessness, which is critical for any planning exercise. Looking first to how the District compares to the rest of the country, it is immediately clear that the District is both performing worse than much of the rest of the country and it is failing to follow national trends towards decreasing levels of homelessness. The highest-level measure and most fundamental statistic to consider is the District’s performance in the Point-in-Time (PIT) estimates in the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD’s) Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress (AHAR). 7 The PIT estimates represent a single night’s survey, conducted each year in January, in communities across the country; PIT surveys are required for recipients of grants under the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. It captures both sheltered and unsheltered homeless populations, and includes details on key subpopulations, like the chronically homeless, veterans, and others. Nationally, the number of homeless people either sheltered or unsheltered decreased by 2.3 percent over 2013-2014, and decreased by 11.2 percent over the longer term of 2007-2014 (see Figure 1). 7 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) Report to Congress. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Oct. 2014. <https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2014-AHAR-Part1.pdf)>. Figure 1: Estimates of Homeless People By Shelter Status, 2007-2014 Partowazam 6 Source: 2014 AHAR to Congress 8 In contrast, the number of homeless people in DC, sheltered or unsheltered, increased by 12.9 percent over 2013-2014 and increased by 45.6 percent over the longer term 2007-2014 9 (see Figure 2). Figure 2: DC Estimates of Homeless People By Household Type, 2010-2014 Source: District of Columbia Interagency Council on Homelessness Strategic Plan, 2015-2020 10 8 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) Report to Congress. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Oct. 2014. <https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2014-AHAR-Part1.pdf)>. 9 Ibid. Partowazam 7 Note, that Figure 1 and 2 are to different scales and cover different time periods, they still illustrate a downward sloping trend line nationally, and an upward sloping trend line in the District, made all the more alarming when considered using the previously mentioned percent change. When compared to other states, the District finds itself amongst the top 5 states with the greatest absolute increase in homeless people in both time periods in HUD’s PIT survey, which is astonishing when considering the size of the District relative to any of the 50 states (see Figure 3). Figure 3: Largest Changes in the Numbers of Homeless People by State, 2007-2014 Source: 2014 AHAR to Congress 11 These comparative trends make the case clear that the District of Columbia faces a disproportionate homelessness challenge, and that planning for even a modest future uncertainty, let alone climate change, is likely to effect a large population in a system that has historically operated beyond its capacity. 10 "Homeward DC: District of Columbia Interagency Council on Homelessness, Strategic Plan, 2015-2020." District of Columbia Interagency Council on Homelessness, Mar. 2015. <http://www.legalclinic.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ICH-Strat-Plan-andAppendices-3-24-15.pdf>. 11 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) Report to Congress. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Oct. 2014. <https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2014-AHAR-Part1.pdf)>. IV. Background on Climate Change Adaptation Planning Partowazam 8 When developing a climate change adaptation plan, there are many frameworks and approaches that an Agency could pursue, depending on their needs. Based on the approach DDOE has already taken, whereby the Agency is developing a district-wide climate change vulnerability assessment and planning document, it makes most sense to choose a framework that uses a tiered approach in which a centralized body coordinates development of individual Agency-specific plans based on common guidance, science, and scenarios. Such an approach closely resembles that taken by the federal government, based on the climate change adaptation requirements set forth in Executive Order (EO) 13514, Federal Leadership in Environmental, Energy, and Economic Performance, and the subsequent EO 13653, Preparing the United States for the Impacts of Climate Change. While it should be noted that this EO has recently been superseded by EO 13693, Planning for Federal Sustainability in the Next Decade, the approach laid out in EO 13514 has served as one of the main drivers of federal climate adaptation efforts in recent years, and its approach should still be considered valid; additionally, the requirements set forth in EO 13653 have not been revoked. EO 13693 does introduce even more specific requirements for federal agencies than EO 13514, however, given its recent signing, implementing instructions are not yet available and thus federal agencies have not yet had an opportunity to begin applying its requirements. Per EO 13514, the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) is required to provide a report on federal agency actions in support of a national adaptation strategy and take further actions as necessary. As a result, federal agencies were to develop climate change adaptation plans, which were subsequently made into a recurring requirement, to be updated regularly, per EO 13563. These federal climate change adaptation plans are structured based on Partowazam 9 EO 13514 Implementing Instructions 12 and Support Document 13 issued by CEQ issued on March 4, 2011. The Implementing Instructions set out five main actions for Agencies: A. Establish an agency climate change adaptation policy B. Increase agency understanding of how the climate is changing C. Apply understanding of climate change to agency mission and operations D. Develop, prioritize, and implement actions E. Evaluate and learn This high-level outline, perhaps with some level of modification, provides an excellent general structure for any District of Columbia agency developing its own climate change adaptation plan. Actions A and B, to establish an agency climate change adaptation plan and to increase agency understanding of how the climate is changing, may be adopted either at the Agency level, as with the federal government, or more broadly at the district-level. Since DDOE is already developing a climate change vulnerability and adaptation assessment, the District of Columbia may opt to either have DDOE establish a climate change adaptation policy for the district, or direct each agency to do so. Likewise, the District may opt to have DDOE provide the authoritative information and analysis of how the climate is changing in the region, or direct each agency to do so. Indeed, per DDOE’s Climate Adaptation Plan Solicitation, these actions may already be underway, and depending on the final product, may be able to be incorporated by reference in agency-specific plans. DDOE’s solicitation already includes language that would increase district-wide understanding of how the climate is changing, such as, “an analysis of the potential impacts of specific climate change impacts, including sea level rise, storm surge 12 "Federal Agency Climate Change Adaptation Planning Implementing Instructions." White House Council on Environmental Quality, 4 Mar. 2011. <https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ceq/adaptation_final_implementing_instructions_3_3.pdf>. 13 "Federal Agency Climate Change Adaptation Planning Support Document." White House Council on Environmental Quality, 4 Mar. 2011. <https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ceq/adaptation_support_document_3_3.pdf> Partowazam 10 flooding, riverine and interior stormwater flooding, extreme storms, and extreme heat. This analysis should identify projections for each impact under various emission scenarios into the future, out to 2020, 2050 and 2100.” 14 While the District of Columbia can choose either a District-wide approach, or an Agency-specific approach, for items A and B, it may be more efficient to leave these planning actions at the District-level since much of the work appears to be already underway. It is clear, however, that item C (to apply understanding of climate change to agency mission and operations) must be taken at the agency-level. It would be inappropriate for a centralized body to identify how the individual operations and mission of an agency interacts with the climate and apply that understanding to its operations. It may, however, be unclear for an agency to realize that it interacts with the climate n the first place; therefore it may be beneficial for DDOE or another body to provide implementing instructions for how this may be done. At the federal level, CEQ’s Support Document lays out steps for how they propose agencies conduct this step via two main questions: • • How is climate change likely to affect the ability of your agency to achieve its mission and strategic goals? How can your agency coordinate and collaborate with other agencies to better manage the effects of climate change? While this is a good starting guideline, it may be difficult for an agency that is not driven by an environmental mission to make the planning leap from its annual operations to a long-term concept like climate. Thus, DDOE guidance, or individual agencies on their own volition, may first choose to ask: • Is your agency’s mission impacted by weather (e.g., rain, snow, heat, etc.) or changes in the season? If so, how? 14 "Notice of Funding Availability and Request for Applications: Developing a Climate Change Adaptation Plan for the District of Columbia." District Department of the Environment, 8 Sept. 2013. <http://ddoe.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ddoe/page_content/attachments/RFA%20%23%202013-9-OPS.pdf>. Partowazam 11 Opening the planning exercise by considering weather and seasons will make it more clear to individual agencies that they can and will be impacted by longer-term trends like climate change. Some agencies will immediately understand how their mission and operations vary seasonally, especially if they are involved in services like snow removal or street sweeping. Others will realize that though their activities aren’t directly tied to weather and seasons, their employees may work in the elements and be exposed to varied weather and seasons, particularly services like trash removal or emergency services. It’s important that this step not only identifies impacts to direct operations, but also covers impacts to funding and strategic planning. If, for example, an agency realizes it spends more money during winter months to complete its missions, it will be important to flag those budget line items as it conducts its subsequent planning steps. Once item C is completed, items D (develop, prioritize, and implement actions) and E (to evaluate and learn) will be easier for agencies to complete on their own. When developing actions, it’s important that agencies cast a wide net and consider their direct operations, the funding for their operations, and the strategic context of their operations. If, for example, an agency realizes it spends more money during winter months to complete its missions (e.g. snow removal), but anticipates spending less in the future due to climate change (i.e., due to less snow), it should consider whether those funds should be used to bolster other strategic initiatives or whether those funds should be used to prepare for a climate change impact that could result in greater cost to agency operations (e.g., increased utility bills due to increased HVAC use in summer months). Subsequently, item E should be relatively straightforward, and should be done on a recurring basis, depending on changes to agency mission, experiences in its implementation, or changing climate projections. Partowazam 12 As applied to homelessness services in the District of Columbia, the subsequent content of this report will focus on exploring how District agencies could develop items C (to apply understanding of climate change to agency mission and operations) and D (develop, prioritize, and implement actions) and E (to evaluate and learn). This will be done at a high-level, since the actual plan must be developed by subject matter experts, practioners, and planners in the actual agencies involved, but will attempt to make select specific policy recommendations based on observed gaps identified as part of the exercise. V. Background on DC Homeless Services Providing homelessness services in the District of Columbia, like any jurisdiction, is a complex system involving many District Agencies and stakeholders. At the highest level, services or coordinated via the District of Columbia’s Interagency Council on Homelessness (ICH), which was established by the Homeless Services Reform Act (HSRA) of 2005. The ICH is comprised of representation from the District’s Department of Human Services, Department of Behavioral Health, Child and Family Services, Department of Housing and Community Development, Department of Health, the DC Housing Authority, the Department of Corrections, the Department of Employment Services, DC Public Schools, HSEMA, the Department of General Services, and emergency services agencies like MPD and DCFD. ICH is meant to facilitate interagency coordination via planning, policymaking, program development, and budgeting, and is required to prepare a strategic plan every five years that sets out the District’s overarching plans. Given the number of stakeholders, and overarching mission of ICH, its clear that no single agency can provide the District’s homelessness services alone, and that any effort to plan for climate impacts should be done across all stakeholders, via ICH. Partowazam 13 DC administers its homelessness services via three overarching Program Models – “Front Porch” Services, which are provided to residents before they reach the front door of the homeless services system; “Interim Housing”, which provides housing that is time limited and designed to provide a stable environment while individuals or families work to find permanent housing; and “Permanent Housing”, in which residents are a leaseholder and can remain as long as they choose. These Program Models are further subdivided in ICH’s most recent Five Year Plan, detailed in Figure 4 below. Figure 4: DC Homeless Services Program Model Categories Source: Homeward DC: DC ICH Strategic Plan, 2015-2020 15 15 "Homeward DC: District of Columbia Interagency Council on Homelessness, Strategic Plan, 2015-2020." District of Columbia Interagency Council on Homelessness, Mar. 2015. <http://www.legalclinic.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ICH-Strat-Plan-andAppendices-3-24-15.pdf>. Partowazam 14 In the context of climate change adaptation planning, the “Emergency Shelter” category should require the greatest attention, especially given the emergency “right to shelter” provisions in HSRA 16, the overarching law that directs the District’s homeless services. Per HSRA § (9)(5), clients of the District’s Continuum of Care (its system of homelessness services) have a right to shelter in severe weather conditions. HSRA further defines severe weather conditions as “the outdoor conditions whenever the actual or forecasted temperature, including the wind chill factor or heat index, falls below 32 degrees Fahrenheit or rises above 95 degrees Fahrenheit.” 17 Notably, ICH’s Five Year Plan describes HSRA’s right to shelter provision as “limited to hypothermia conditions only” and questions whether it is appropriate to expand the right to shelter and indicates that data does not exist on whether families and individuals that do not receive shelter in summer months would otherwise seek emergency shelter. Given this data gap, and seemingly incomplete description of HSRA’s right to shelter provision, the Five Year Plan defers to future work by the Department of Human Services to better define shelter availability in summer months; this policy decision has a clear climate change impact and should be considered when developing an adaptation plan. Additionally, HSRA § (5)(9) requires ICH to develop an annual winter plan, consistent with the right of clients to shelter in severe weather conditions, describing how member agencies will coordinate to provide hypothermia shelter and identify sites that will be used as hypothermia shelters. The overlap between Interim Housing, which serves the majority of households entering the homeless services system, and HSRA’s mandated right to shelter in severe weather conditions, makes climate adaptation in the clear and immediate interest of the District’s homelessness services. 16 "The Homeless Services Reform Act of 2005." Interagency Council on Homelessness. District of Columbia Government Oct. 2005. Web. <http://ich.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ich/publication/attachments/HSRActOf2005.pdf>. 17 Ibid. VI. Climate Change Projections Partowazam 15 Understanding the existing climate of the District of Columbia and how it may change in the future is a fundamental step of climate change adaptation planning. Data and reports can often be difficult to interpret, especially for agencies or planners unaccustomed to environmental missions or scientific backgrounds. Furthermore, different levels of detail, in terms of climate change projections and climate variables, may be appropriate for different Agencies or services; those tasked with design or engineering standards may need far finer detail and certainty due to the longevity and criticality of their mission. For the sake of this report, the emphasis will be placed on explaining trends most likely to impact city services, particularly homelessness services, followed by a discussion of the sorts of guidance or scenarios that DDOE may consider providing to District Agencies conducting their own climate adaptation plans. The first stop for planners identifying climate change impacts for District of Columbia’s region is the National Climate Assessment’s chapter on Climate Change Impacts on the Northeast. 18 While the District of Columbia is on the southern border of this region, it is still appropriate for planning purposes. In reading documents like the National Climate Assessment, its important to hone in on impacts most relevant to the Agency or service one is planning for. While discussion of hurricanes and sea level rise is critically important for those planning for emergency services or critical infrastructure, the most important information for most Agencies and services is extremes in temperature, since they may have employees or services administered outdoors, or have missions based on such variables (e.g., cooling shelters). 18 Horton, R., G. Yohe, W. Easterling, R. Kates, M. Ruth, E. Sussman, A. Whelchel, D. Wolfe, and F. Lipschultz, 2014: Ch. 16: Northeast. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 16-1-nn. <http://s3.amazonaws.com/nca2014/low/NCA3_Full_Report_16_Northeast_LowRes.pdf?download=1> Partowazam 16 In terms of extreme heat, the National Climate Assessment (NCA) tells us that the District of Columbia should expect an overall annual increase in days over 90°F (on average between 20412070, compared to average between 1971-2000). While the NCA presents multiple scenarios, the District will increase from an average of approximately 20-30 days over 90°F per year to approximately 50-70 days over 90°F per year, or approximately a doubling in this extreme. For planning purposes, this is important for agencies that have employees or customers that administer or receive services in hot weather, or agencies that have services or expenses associated hot weather (e.g., increased utility bills for cooling or hyperthermia shelters); while cost or service demand may not necessarily double, it is likely that either would increase by some proportion to be assessed by planners. More detail on this extreme is included in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) Technical Report on the Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment, which includes information on other extremes, like number of days above 95°F , including in Figure 5 below. 19 19 Kenneth E. Kunkel, Laura E. Stevens, Scott E. Stevens, Liqiang Sun, Emily Janssen, Donald Wuebbles, Jessica Rennells, Art Degaetano, J. Greg Dobson. "NOAA Technical Report on Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment." Climate of the Northeast U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Jan. 2013. <http://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/technical_reports/NOAA_NESDIS_Tech_Report_142-1-Climate_of_the_Northeast_U.S.pdf>. Partowazam 17 Figure 5: Simulated difference the mean annual number of days with a max temperature greater than 95°F for the Northeast region, for the 2041-2070 time period with respect to the reference period of 1980-2000 Source: NOAA Technical Report on the Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment 20 Similar data on extreme cold is also available form NOAA’s technical document. If one chooses to focus on number of days with a minimum temperature below 10°F, we see the District decreasing from an average range of 50-70 days with a minimum temperature below 10°F to an average of 25-50 days with a minimum temperature below 10°F, or a more precise decrease of nearly 50 percent; more detail on this projection is included in Figure 6, below. This means that agencies that have a cost associated with cold weather may see savings in the future, and may choose to shift their allocated budgets towards other areas (e.g., to summer expenses). 20 Kenneth E. Kunkel, Laura E. Stevens, Scott E. Stevens, Liqiang Sun, Emily Janssen, Donald Wuebbles, Jessica Rennells, Art Degaetano, J. Greg Dobson. "NOAA Technical Report on Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment." Climate of the Northeast U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Jan. 2013. <http://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/technical_reports/NOAA_NESDIS_Tech_Report_142-1-Climate_of_the_Northeast_U.S.pdf>. Partowazam 18 Figure 6: Simulated difference the mean annual number of days with a minimum temperature below 10°F for the Northeast region, for the 2041-2070 time period with respect to the reference period of 1980-2000 Source: NOAA Technical Report on the Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment 21 VII. Climate Change Adaptation Recommendations for DC Homeless Services Based on the above description of the District’s existing homelessness services and the description of the District’s future climate, there are several key adaptive actions that the ICH may consider taking. While funding availability for these actions will ultimately determine their implementation, when considered in the context of a climate adaptation plan, planners may be able to identify adjustments that rebalance seasonal budgets appropriately. The three actions described below may be implemented as a matter of policy, though lawmakers looking to update 21 Kenneth E. Kunkel, Laura E. Stevens, Scott E. Stevens, Liqiang Sun, Emily Janssen, Donald Wuebbles, Jessica Rennells, Art Degaetano, J. Greg Dobson. "NOAA Technical Report on Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment." Climate of the Northeast U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Jan. 2013. <http://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/technical_reports/NOAA_NESDIS_Tech_Report_142-1-Climate_of_the_Northeast_U.S.pdf>. Partowazam 19 the District’s homelessness services may also consider mandating them by law, to compliment existing requirements in HSRA. Recommendation 1: As a matter of policy, conduct a summer PIT survey While HUD only mandates biannual PIT surveys for its grant recipients, ICH should consider conducting its own PIT surveys six months following the January HUD PIT survey (i.e., in July). This will allow ICH to establish a seasonal reference and point of comparison between its winter shelter rates and its demand for summer shelter. This is an existing data gap that already negatively impacts ICH planning, and is described on page 43 in its Five Year Plan, “Families turned away during the summer may spend months couch surfing, or worse, living in dangerous/violent situations. We do not have exact data on the number of households that present at [Virginia Williams Family Resource Center] for assistance during the summer and return again during hypothermia season, but certainly some percentage of households do, and by the time they return, their situations have often deteriorated, making it that much more difficult to help them stabilize.” Additionally, “Unfortunately, it’s difficult to know whether we would see the same number of households we currently see, with placements more evenly distributed throughout the year, or if we would see placement rates in the summer that mirror the winter months, thereby increasing our shelter capacity needs.” Given that HSRA mandates a right to shelter when the heat index exceeds 95°F, having improved data on shelter demand during the summer will help inform how best to allocate shelter capacity and availability throughout the year. Additionally, based on the above climate projections, the District is expected to see its total number of days exceeding a 95°F nearly double in the coming decades, meaning the District will have more days in which it is required to Partowazam 20 provide shelter. Conversely, as the District sees its days below 32°F nearly halve over the same period, it may choose to allocate funds away from winter months and towards summer months. Recommendation 2: As a matter of policy, develop an annual summer shelter plan While HSRA § (5)(9) currently only requires ICH to prepare a winter plan each year, as a matter of policy ICH should consider developing a similar, complementary summer plan each year. Based on the climate trends discussed above, the District is expected to see its days exceeding 95°F nearly double in the coming decades, while its days below 32°F degrees will nearly halve. While ICH should not cease developing a winter plan (both for practical purposes and for legal requirements), developing a similarly structured summer plan will help the District better plan for its future demand. Development of the summer plan will be complemented by Recommendation 1, whereby improved summer demand data collected via a summer PIT survey will more accurately inform how many beds to allocate and distribute. Recommendation 3: As a matter of policy, implement existing summer right to shelter requirements While HSRA § (5)(9) currently mandates a right to shelter in severe weather conditions, which it defines as “the outdoor conditions whenever the actual or forecasted temperature, including the wind chill factor or heat index, falls below 32 degrees Fahrenheit or rises above 95 degrees Fahrenheit.” This seemingly conflicts with, ICH’s Five Year Plan repeated description that HSRA’s right to shelter provision as “limited to hypothermia conditions only”. While ICH’s Five Year Plan takes time on page 43 to discuss whether year-round access to shelter for families should be guaranteed, it fails to accurately describe that there is an existing right to shelter in hyperthermia season (albeit not to overnight shelter), in addition to hypothermia season. While certainly more study is needed to determine whether a truly year-round right to shelter is Partowazam 21 strategically appropriate or financially feasible, implementing the existing requirement to guarantee shelter during summer severe weather conditions, and possibly extend it to include an overnight right to shelter, will help improve access to shelters with a more modest budgetary impact than a year-round right to shelter. Implementing this requirement now, alongside a summer PIT survey, will also help justify budgetary adjustments that may need to be made as the District sees more days that exceed 95°F and fewer days below 32°F. VIII. Conclusion To effectively prepare and adapt the District of Columbia to the impacts of climate change, climate adaptation planning should be conducted at the agency and city service level. Existing efforts by DDOE are expected to identify District-wide vulnerabilities and recommended adaptive strategies for different climate change scenarios; these same scenarios, along with additional guidance, should be used by DDOE in partnership with District agencies to develop tailored adaptation plans for their services. This approach is consistent with the process developed by the federal government, whereby various Executive Orders issue instruct individual agencies to prepare for the impacts of climate change by developing plans consistent with parameters set out by CEQ. Different District agencies may mimic the approach taken in this report, in which existing programs and climate projections are considered to identify recommended adaptive actions, consistent with the approach outlined at the federal level. To better prepare the District’s homeless services for the impacts of climate change, it is recommended that the ICH take the following actions: 1. As a matter of policy, conduct a summer Point In Time (PIT) survey 2. As a matter of policy, develop an annual summer shelter plan Partowazam 22 3. As a matter of policy, implement existing and expand summer right to shelter requirements