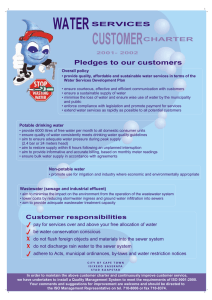

W , C , p

advertisement