S Wraparound and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports in the Schools

advertisement

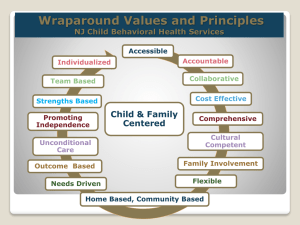

jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 171 Wraparound and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports in the Schools LUCILLE EBER, GEORGE SUGAI, CARL R. SMITH, AND TERRANCE M. SCOTT S TUDENTS WHO DISPLAY SEVERE EMO- tional and behavior problems in our schools represent a relatively small proportion of a school’s total student enrollment; however, they require significant amounts of expertise, time, and resources. They can also be major destabilizing influences in schools. Although most educators are dedicated to meeting the academic and behavioral needs of these students, they become frustrated by their inability to establish and sustain effective programming options. In addition, for many of these students, the development and implementation of effective behavior supports requires active and efficient involvement of more than just school personnel—in particular, it requires the family to be involved. Together, the wraparound process (Burns & Goldman, 1999) and the positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) approach (Sugai, Horner, et al., 2000) offer a potentially important and efficient means of improving the educational and behavioral programming of students with or at risk of developing severe problem behaviors. The wraparound process is a tool for building constructive relationships and support networks among youth with emoJOURNAL OF EMOTIONAL Effective school-based programming for students with behavioral difficulties continues to challenge educators. Consensus is growing that prevention and early intervention must be prioritized, agencies must collaborate, and family–school partnerships must be improved so that effective interventions are actually implemented.This article explores how the school-based wraparound approach and a school-wide systems approach to positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) work together to create more effective school environments and improved outcomes for students with or at risk of behavioral challenges. Complementary aspects of these wraparound and PBIS approaches are described, and future directions for research and practice are explored. tional and behavioral disorders (EBD) and their families, teachers, and other caregivers. Careful and systematic application of the wraparound process can increase the likelihood that appropriate supports and interventions are adopted, implemented, and sustained (Burns, Schoenwald, Burchard, Faw, & Santos, 2000; Eber, 1997, 1999), thereby leading to improved behavior functioning for a given youth. Programming for these students is more likely to be effective in school environments that support and promote positive, proactive behavior among all students. PBIS is a systems approach for establishing a continuum of proactive, positive discipline procedures for all students and staff members in all types of school settings (Sugai, Sprague, Horner, & Walker, 2000). Based on a three-tiered AND B E H AV I O R A L DISORDERS, FALL 2002, prevention model, PBIS offers a consistent research-based approach for promoting prosocial behavior of (a) students without chronic problems ( primary prevention), (b) those students at risk for problem behavior (secondary prevention), and (c) students with intensive behavioral needs (tertiary prevention). Within this model, elements of the wraparound process are evident, especially at the secondary and tertiary levels, and the comprehensive wraparound process is used for implementing tertiary interventions for students with the most intensive needs. The application of school-wide PBIS enhances wraparound for students with intensive needs by providing an environment of proactive interventions across all students and a school- and communitywide “systems” approach for prevention VOL. 10, NO. 3 , PAG E S 1 7 1 – 1 8 0 171 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 172 and early intervention. PBIS augments wraparound by giving educators, family members, students, and community agency staff members access to researchvalidated practices and processes for changing behavior across the range of student life domains. The purpose of this article is to describe how a school-wide approach to PBIS complements the school-based wraparound process to improve outcomes for students with severe emotional and behavioral problems. We describe the background and need for wraparound and PBIS; define and describe the wraparound process in schools, including the legal context of expectations for school personnel under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1997 (IDEA ’97); describe the features of school environments that support the wraparound process; present guidelines for the development of effective wraparound teams and plans within the context of schoolwide PBIS; and propose future directions for practice and research to improve our understanding and use of wraparound and school-wide PBIS approaches. BACKGROUND AND NEED The need for collaborative and comprehensive systems that identify and organize relevant services for students with EBD and their families has been clearly indicated in the literature (Knitzer, Steinberg, & Fleisch, 1990; S. W. Smith & Coutinho, 1997; Sugai, Horner, & Sprague, 1999). Children and youth with EBD have not fared well in our public schools. For example, compared to typical students and students with other disabilities, students with EBD have disproportionately higher rates of dropout and academic failure, and they are more likely to be arrested, poor, unemployed, involved with illicit drugs, and teen parents (Carson, Sitlington, & Frank, 1995; Kauffman, 1999a; Nelson & Pearson, 1994; U.S. Department of Education, 1998). Students who are labeled EBD also are among the most likely of any disability group to be educated in restrictive and exclusionary placements (U.S. Department of Education, 1998). Even more disturbing is the fact that these stu- 172 JOURNAL OF EMOTIONAL AND dents are more likely to spiral through multiple special education, mental health, juvenile justice, and child welfare services and agencies and to have a poor prognosis for success (Koyanagi & Gaines, 1993). Although collaborative efforts have shown some promising outcomes for youth and systems (Bruns, Burchard, & Yoe, 1995; Eber, Rolf, & Schrieber, 1996; Malloy, Cheney, & Cormier, 1998; Stroul, 1993), blending resources, language, decision making, and best practices across systems and disciplines remains a complex and sometimes daunting task (Malloy et al., 1998; Schorr & Julius, 1998). In addition, discipline-based differences regarding treatment choice and priorities, implementation fidelity, criteria for treatment success, and outcome accountability create slow and ineffectual systems and processes. These expectations may be particularly relevant as we face challenges in designing and providing appropriate programs for youth who may be involved with the juvenile justice system or who may have significant mental health needs (Coalition for Juvenile Justice, 2000). Many of these same interdisciplinary hurdles also are apparent even within the school itself (e.g., categorical classroom delivery, multiple teaming processes). Such issues hamper efforts to provide the effective and sustainable behavior supports necessary to establish and sustain competent school cultures or host environments that support the adoption and sustained use of research-validated practices and systems (Horner & Sugai, 1999; Latham, 1988; Zins & Ponti, 1990). Under these circumstances, disagreements, cynicism, and lack of collaboration result in inconsistent policy and practice. Curriculum decisions tend not to be databased, and when a practice is adopted, it often is implemented incompletely, inconsistently, or for too short a period of time (e.g., 2 to 4 years; Latham, 1988). Failures with practice create increased cynicism and dissatisfaction, promoting new practices that are adopted with similarly insufficient zeal. C. Smith (2000) suggested that the behavioral and discipline expectations of IDEA ’97 are at risk for such broad-based systemic failure unless sustained training efforts and system B E H AV I O R A L DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. supports are established to ensure that school personnel reliably demonstrate the skills required to meet the mandate (e.g., conducting functional behavioral assessments and designing behavioral intervention programs). These conditions and challenges inhibit systemic supports and processes and interfere with sufficient and sustained provision of effective and efficient educational programs for students with emotional and behavioral problems. One response to improving the adoption and sustained implementation of effective practices involves a careful consideration of both the host environment (Zins & Ponti, 1990) in which those practices are being considered and the manner and degree to which planning among key stakeholders is conducted. Such systemschange consideration reflects the intimate connection of PBIS and wraparound adoption across domains and stakeholders (Hienemann & Dunlap, 2001; Knoster, Villa, & Thousand, 2000). Such systemic adoption of best practices is consistent with the positions being advocated by various professional and parent advocacy organizations (see, e.g., Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorders, 1998; U.S. Department of Education, 1998). DEFINING AND DESCRIBING WRAPAROUND The wraparound process has emerged from the concept known as system of care, which is a community-based approach to providing comprehensive, integrated services through multiple professionals and agencies and in collaboration with families (Stroul & Freidman, 1986). There has been a proliferation of demonstration projects and systems-change initiatives that attempt to create (a) collaborative systems in local communities across the United States and (b) positive change for these children, youth, and their families (Burns & Goldman, 1999; Hoagwood, 1997; Stroul, 1993). Wraparound, an innovative approach for implementing individualized, comprehensive services within a system of care, has developed as a promising practice for improving out10, NO. 3 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 173 comes for children and youth with EBD and their families (Burns & Goldman; Eber et al., 1996; Malloy et al., 1998). Wraparound is a philosophy of care with a defined planning process for creating a unique plan for a child and family that is designed to achieve a set of outcomes that reflect their voices and choices (Burns & Goldman, 1999). Wraparound incorporates a family-centered and strength-based philosophy of care to guide service planning for students with EBD and their families. It involves all services and strategies necessary to meet the individual needs of students and their families. The child, family members, and their team of natural support and professional providers define the needs and collectively shape and create the supports, services, and interventions linked to agreedupon outcomes. The 10 elements of wraparound considered to be essential to the process are listed in Table 1. Although primarily initiated through mental health or child welfare systems, the direct application of wraparound in schools has led to reports of improved outcomes for students with EBD in a variety of educational settings, including general education classrooms (Eber, 1996; Eber & Nelson, 1997). Application through community-based transitional programs for young adults has increased rates of school completion, career focus, job performance, and other postschool indicators (Malloy et al., 1998). Wraparound is not a service or a set of services; it is a planning process. This process is used to build consensus within a team of professionals, family members, and natural support providers to improve the effectiveness, efficiency, and relevance of supports and services developed for children and their families. This interagency process emphasizes strengthbased interventions that blend the perspectives of all involved persons to ensure success across life domains and settings. Careful monitoring of implementation and outcomes is an integral part of the process. The wraparound process brings teachers, families, and community representatives together to commit unconditionally to a way of conducting problem solving JOURNAL OF TABLE 1 Elements of Wraparound 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Community based Individualized and strength based Culturally competent Families as full and active partners Team-based process involving family, child, natural supports, agencies, and community supports Flexible approach and funding Balance of formal and informal community and family resources Unconditional commitment Development and implementation of an individualized service/support plan based on a community/neighborhood, interagency, collaborative process Outcomes determined and measured through the team process Note. Based on data from Burns and Goldman (1999). and planning that gives equal importance and support to the child and his or her family, teachers, and other caregivers. A key element is blending perspectives to achieve consensus on specific and individualized desired outcomes (e.g., improved academic and behavioral results, greater capacity for family participation, enhanced school–home transitions). In addition, the supports that family members and educators need to effectively implement interventions for the child also must be considered. Fundamental to this process is incorporating a strengths perspective that bases the selection and implementation of all interventions, supports, and services on the needs and outcomes identified by the family, child, and teacher (e.g., social behavior gains, personal goals, academic performance, positive and cohesive family activities, extracurricular and/or work opportunities). Therefore, behavior support planning is initiated from student and family personal, interpersonal, and academic strengths rather than from their weaknesses, deficits, and problem behaviors. Instead of being told what services and supports professionals will provide, the family members and the child are asked to indicate their strengths and prioritize their needs. They will select team members who they feel can support and assist them in achieving their goals. Once commitment and consensus regarding roles, strengths, and needs are established, team EMOTIONAL AND B E H AV I O R A L members engage in a process that results in carefully designed interventions that are directly linked to clearly stated outcomes. For children and families, supports and services might include respite; mentoring; peer supports; parent partners; or basic assistance in such areas as housing, transportation, job assistance, childcare, or health and safety. For schools, supports and services in wraparound plans can address quality programming and legal/compliance issues that may include functional behavioral assessment; instructional accommodations for strengthbased academic, behavioral, and social skills; and consultation and supports for teachers. These services may be provided by school-based personnel or on an asneeded basis by other qualified persons or agencies identified by the team. An effective child–family wraparound team is prepared to step outside of the box of the usual categorical service options to create or reorganize services based on unique needs and circumstances. Combining natural supports (e.g., childcare, transportation, mentors, parent-to-parent network) with interventions (e.g., behavioral strategies, social skills instruction, reading instruction, therapy, medication) can lead to more effective outcomes. Wraparound planning has resulted in decreasing the numbers of out-of-home and restrictive school placements while at the same time improving behavioral, academic, social, and postschool adjustment DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. 10, NO. 3 173 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 174 indicators for students with EBD (Bruns et al., 1995; Burns et al., 2000; Eber et al., 1996; Eber & Nelson, 1997; Malloy et al., 1998). WRAPAROUND IN SCHOOLS The wraparound process can be integrated into school-based planning for students with special needs regardless of the type of special education label or multiagency involvement (Eber & Nelson, 1997). Although wraparound originally was initiated for those students with the most chronic and intensive emotional and behavioral needs (Burchard, Burchard, Sewell, & VanDenBerg, 1993; VanDenBerg & Grealish, 1996), many schools and communities also have begun integrating this approach with students whose schools have recognized them as being at risk for chronic problems (Burns et al., 2000; Eber, 1998). This includes students who may not have come to the attention of mental health, juvenile justice, or other community agencies but for whom the school and/or family have recognized that such attention is likely if effective interventions are not provided. For these students, elements of the wraparound process are integrated into prevention planning (i.e., student support teams or teacher assistance teams) or through the Individualized Education Program (IEP) process. School systems also are applying the wraparound process directly through special education for students with the most intensive and complex needs, which particularly means students with EBD (Eber, 1996, 1998; Eber & Nelson, 1997). Bringing family members, friends, and other natural support persons together with teachers, behavior specialists, and other professionals involved with the student and family is essential to the planning process because teams must combine the supports and services directed toward reducing risk factors (Walker & Sprague, 1999) with effective clinical, medical, behavioral, and instructional strategies. In this manner, the wraparound process creates a team context within which effective behavioral and instructional strategies are more likely to occur. 174 JOURNAL OF EMOTIONAL AND Effective wraparound planning requires skilled facilitation of the planning process within the child–family team. Schools can provide such facilitation for greater numbers of students because they have characteristics not available in other community agencies. For example, schools have (a) structures and routines for daily contact with children and regular interactions with their families; (b) broad-based support services (e.g., nursing, psychological/counseling, academic remediation); (c) formalized individualized educational planning through special education; (d) integrated learning opportunities; and (e) multiple opportunities for exposure and interactions with positive peer and adult role models. The wraparound process is applied in schools to increase the family/child voice in the design of school-based interventions and to achieve better outcomes across settings (Eber, 1999). In addition, from a policy and legal perspective, schools are being called upon to provide these interventions as a part of the related services that must be provided by schools if they are determined to be needed for a student to receive an appropriate program (Maag & Katsiyannis, 1996). CONNECTIONS WITH SPECIAL EDUCATION AND THE IEP The wraparound process is consistent with the values and mandates of the original special education law (Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975) as well as the reauthorized version, IDEA (Skiba & Peterson, 2000; C. Smith, 2000). Wraparound can be used to guide the development of effective IEPs that reflect the family’s voice and include outcomebased supports, services, and interventions (Eber & Nelson, 1997). In fact, use of this strength-based process has helped teams move from placement-driven discussions, often filled with conflict and blame placing among schools, agencies, and families, to productive problemsolving sessions where families, teachers, and students are heard and supported. School-based wraparound planning guides the implementation of interventions that develop and support academic and behavB E H AV I O R A L DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. ioral skills needed for students to succeed at school, at home, and in the community. Furthermore, intervention integrity, described by C. Smith as the degree to which an IEP team can develop interventions that are calculated to provide meaningful benefit for a student being served, would be more likely to emerge from such a process. School-based wraparound planning creates access for more family and community supports that can enhance the effectiveness of academic and behavioral interventions for students with EBD. Team attention to teacher concerns and needs results in a greater willingness by teachers to problem-solve with other professionals and with families. In addition to the discipline provisions of IDEA ’97 delineated previously, the IEP provisions of these amendments specify that under “special considerations,” if a student’s behavior is interfering with his or her learning or the learning of others, the IEP team will consider the use of positive behavioral supports needed to address such behavior (see, e.g., Turnbull, Wilcox, Stowe, & Turnbull, 2001). Our experiences suggest that careful implementation of the wraparound process creates a context for effective implementation of research-based behavioral, instructional, and clinical interventions while meeting our legal and procedural duties as educators. Although wraparound is consistent with the intent of the IEP process, implementation differences have occurred as the IEP process has evolved with a mandate focus over the past 30 years. Wraparound teams include individuals other than mandated special education personnel. Natural support persons, community representatives, and individuals who have positive relationships with the student and family are sought as members. Wraparound plans go beyond the IEP itself to include supports and services for home and community settings, many of which do not need to be included in the actual IEP document. Wraparound plans are designed to fit an individual student’s unique needs as opposed to fitting a student to a program (Eber & Nelson, 1997). This individualization includes identifying, accessing, and creating resources and strate10, NO. 3 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 175 gies to enhance the school’s capacity to effectively educate the student. Pinpointing effective instructional and behavioral interventions and comprehensive support plans for students and teachers is essential. Application of the wraparound process requires professionals and family members to think differently about each other and about the needs of a student with EBD. Instead of focusing on where the student will be placed or what consequences he or she will receive for inappropriate behavior, the team problemsolves concerning needs identified by the family, the student, and the student’s teacher (e.g., having friends, learning to read, staying in school). When the teacher and family define these needs, the supports and services associated with the selected interventions will be practical and accepted (Eber, 1999). Supported by skilled education staff members, the team proceeds with the identification and application of strategies that will be effective in producing positive social and academic skills (Eber, 1999). When the voices of those who spend the most time with the student are heard and united, realistic and creative problem solving, positive school–family relationships, and the design of effective interventions are facilitated. The family and child should feel it is their team and their plan. SCHOOL FEATURES THAT SUPPORT WRAPAROUND The wraparound process organizes and supports programming for students with EBD and for those who are at risk for significant problem behaviors and their families. Wraparound represents only one aspect of a comprehensive system of positive behavior support in schools, however. Increased concerns about school safety have broadened the focus beyond students who have been identified as having EBD, forcing educators to look closely at how behavior is related to contexts and conditions in the larger school environment. Prevention of and early intervention for EBD are now recognized as critical needs in schools (Sprague & Walker, JOURNAL OF 2000; Walker et al., 1996). Professionals and parents realize that strategies such as conducting functional behavioral assessments or designing and implementing behavioral intervention programs should be considered long before a student is facing major disciplinary actions by school officials (Iowa Department of Education, 1998). As with the systems changes in mental health and child welfare, general and special educators are recognizing the need to adopt a proactive systems approach toward student behavior. Reactive and punitive discipline systems are not achieving positive results, and more educators and other professionals are seeing the need for system-wide approaches that will produce the prosocial behaviors required for safer school environments (Council for Exceptional Children, 1999; Sugai & Horner, 1999–2000). Recently, educators have been encouraged to conceptualize and apply a continuum of positive behavior interventions across all students in a school (Kerr & Nelson, 1998; Lewis & Sugai, 1999; Scott & Nelson, 1999b; Sugai & Horner, 1999– 2000; Walker et al., 1996). This continuum illustrates the need to combine the technology of effective behavior change with interagency collaborative approaches to meet the needs of all children and youth. Building on Zins and Ponti’s (1990) concept of effective “host environments,” Sugai and colleagues (Sugai et al., 2000) proposed that interventions for students with the most complex needs be enhanced by building consistent structures for organizing and applying effective behavior interventions throughout school environments. Figure 1 illustrates this continuum of PBIS and the features of the three-tiered approach, which is based on the following assumptions: • A majority (approximately 80%– 90%) of students in schools will not demonstrate serious problem behavior if a well-defined, consistent, researchbased, and universal system of positive behavior support is implemented throughout the school (Colvin, Kameenui, & Sugai, 1993; Lewis & Sugai, 1999). These school-wide discipline systems emphasize the identiEMOTIONAL AND B E H AV I O R A L fication and description of expected behaviors for all students and include strategies that adults use to teach and encourage prosocial skills in the school. In addition, a continuum of procedures to discourage rule violations and formatively monitor the effectiveness of the school-wide system are put in place. • Targeted interventions are designed for the relatively small number (approximately 5%–15%) of students who do not respond to the universal approaches. These interventions are more specialized and intensive but are administered individually or in small groups (Sprague, Sugai, & Walker, 1998). Moreover, these elements incorporate aspects of the wraparound process, including (a) functional assessment–based behavior support planning that considers the strengths and needs of the student and his or her family, and the teaching and positive reinforcement of prosocial behaviors to replace problem behavior; (b) behavioral and academic interventions that include supports for the student’s caregivers in the school, home, or community; and (c) collaboration with mental health or community agencies on targeted interventions for students and their families at the first indication of need. • Students who have chronic and intensive emotional and behavior problems (approximately 1%–7%) warrant a comprehensive plan covering the home, the school, and the community. Intervention and support features are similar to those in targeted interventions, but they are more individualized, are of higher intensity, and involve more comprehensive planning and interventions. A family-centered team that is unique to each student ensures that the family and student are heard and that consensus is achieved regarding needs and outcomes. Careful analysis of the student’s unique needs in life domains (e.g., safety, medical, social, psychological, familial, vocational) drive the planning process. Effective behavioral and academic interventions also represent an DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. 10, NO. 3 175 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 176 FIGURE 1. Continuum of positive behavior interventions and supports. important part of comprehensive wraparound plans for these students. This concept of a continuum of behavior support offers a context for understanding how wraparound and PBIS are connected in schools. The emphasis is on (a) a positive, proactive continuum of positive behavior supports; (b) more intensive, specialized, and individualized interventions as problem behaviors and needs intensify; (c) a family-centered, teambased planning process; and (d) comprehensive planning that considers the strengths and needs of the student, the family, the teacher, and other natural support caregivers. The goal is to increase the impact of academic and behavioral interventions by improving the effectiveness, efficiency, and relevance of behavior support planning that considers the student and his or her family’s strengths and risk factors. Walker and Sprague (1999) advocated connecting wraparound approaches and positive behavior strategies to improve and sustain outcomes: Altering a student’s life course usually requires that a risk factor’s approach be used that leads to a comprehensive intervention 176 JOURNAL OF EMOTIONAL AND involving caregivers, teachers, and peers at a minimum. To divert students at risk for BD from an at-risk life path, it is essential that key social agents in students’ lives be directly involved in the intervention, due to the complexity and spillover factors that characterize students with BD. (p. 336) WRAPAROUND PROCESS FEATURES WITHIN SCHOOL-WIDE PBIS Although dynamic and individualized, the wraparound process has defined features and processes. In this section, we briefly discuss the steps in the wraparound process and describe guidelines that improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and relevance of the process outcomes. Wraparound Process Steps The wraparound planning process has been described as a series of steps that are conducted by a team unique to an individual child and family. To maximize outcomes, these steps should be carefully followed, written plans developed and implemented, and effectiveness monitored on an ongoing basis. B E H AV I O R A L DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. Step 1: Engage in Initial Conversations. Before conducting a wraparound team meeting, the first step is to engage family members and members of their natural support network in individual conversations about their ideas, frustrations, views, values, and dreams regarding the child in question. This step is important not only for creating trusting relationships and establishing a consensus-building environment but also for collecting information used to design effective interventions. During these individual conversations, the team facilitator can encourage family members and teachers to describe their past and current efforts and successes, share their concerns and frustrations, explain their goal for their role with the student, and identify the strengths of the family and other members of the student’s support network. One of the most important outcomes of these initial conversations is to identify information (e.g., strengths, needs, behavioral data, concerns of family) used to design interventions that directly address outcomes in major life domains (e.g., academic, behavioral, personal, vocational) across home, school, and community contexts. Other outcomes are to establish trust and rapport and solicit involvement in a strengthbased team process. Step 2: Start the Meeting with Strengths. The initial meeting begins with a summary of the strengths identified during the initial conversations. The facilitator ensures that different perspectives of the child’s strengths (i.e., teacher, student, family) are addressed across multiple life domains (i.e., social, educational, physical). Describing the strengths of the family, the teachers, and other providers is also encouraged. All strengths should be stated in specific and functional terms (e.g., likes to help younger kids in wheelchairs in the hallway) as opposed to a list of adjectives (e.g., nice kid). The strengths profile should be reviewed and updated at all subsequent meetings. Step 3: Develop a Mission Statement. A mission statement is a clear, concise description of why this team exists. It should be agreed upon by all the team members 10, NO. 3 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 177 who may have an active role with the student. This simple statement should guide the team’s actions to ensure that activities are connected to the mission. The following is an example of a mission statement: “The student will live at home and succeed at school.” Step 4: Identify Needs Across Domains. Based on information obtained during initial conversations, the team summarizes all the needs of the student and his or her family across the life domains. The facilitator guides the team toward normalized needs or replacement behaviors with questions such as, “What does this student need to be more like a student who is doing OK in our school and community?” The student, family members, and the teacher are encouraged to express all the needs they believe must be met for the student to succeed. take ownership of the intervention design. Facilitators must ask team members whether the proposed action will work for them. Teams must take the time to confirm commitment to task completion and to ensure common understanding of the intervention’s procedures by those committed to implementation. Step 8: Document the Plan: Evaluate, Refine, Monitor, and Transition. A clear consensus regarding needs, strategies, and outcomes sets the context for a defined team evaluation/monitoring process. Each meeting should begin with a review and progress rating of actions defined at the previous meeting. If a need has not been met to the team’s satisfaction, refining, redesigning, or reevaluating available data should take place. Integration Guidelines Step 5: Prioritize Needs. The facilitator guides the team to consensus regarding which specific needs the team will strategize about at the current meeting and which needs will be addressed at subsequent meetings. The individuals who spend the most time with the student or have the most responsibility for him or her (e.g., family members, teachers) should have the primary role in determining the priority of needs. Step 6: Develop Actions. The team develops specific strategies for meeting needs and clearly defined outcomes. The team must decide which needs are ready for immediate action and which require additional information. Initial actions may then address gathering additional information (e.g., conducting functional or reading assessments) so that interventions may be designed. For other need areas, the team may have enough information to immediately move to action planning (e.g., creating a daily communication strategy between home and school, obtaining transportation to medical appointments, selecting specific instructional interventions). Step 7: Assign Tasks/Solicit Commitments. The person or persons responsible for implementing given actions should JOURNAL OF Effective wraparound plans are the byproduct of effective child/family teams and effective and efficient meetings, and they can blend easily with PBIS practices and systems. Attending to the following guidelines can maximize the outcomes of the wraparound process and the extent to which the wraparound process and PBIS practices and systems are integrated. Use a Highly Trained Facilitator. If the wraparound process is to be successful, someone must be responsible for ensuring that the team process is conducted efficiently and effectively. Potential school-based PBIS facilitators are individuals who have responsibility for leading IEP teams and intervention planning for students with or at risk for EBD (e.g., social workers, psychologists, intervention specialists, team leaders) and who may possess many of the skills needed for effective wraparound facilitation. These required skills include (a) recognizing and blending differences in perspectives among team members; (b) guiding consensus and problem solving; (c) recognizing antecedents, setting events, and replacement behaviors for problem behaviors; (d) accessing needed services and persons skilled in providing the appropriEMOTIONAL AND B E H AV I O R A L ate interventions and supports; (e) ensuring that all team members have a participatory role in the process; and (f) linking all supports, services, and interventions to outcomes and guiding the team in monitoring effectiveness over time. Focus on Strengths, Needs, and Perspectives. Similar to the function-based approach for the behavior support planning process (Sugai & Horner, 1999– 2000; Sugai, Lewis-Palmer, & HaganBurke, 1999–2000; Todd, Horner, Sugai, & Sprague, 1999), effective wraparound plans are the result of a teaming process that maintains a focus on strengths as a means of addressing needs. Hearing each other’s perspectives fosters active participation and team ownership; considers the constraints that each member of the team brings to the conversation (either personally or because of their agency/job role); creates a safe environment in which team members are able to express concerns; and collaboratively develops solutions that are designed to meet student, family, and teacher needs across situations and settings. Prepare for Team Meetings. Before conducting wraparound team meetings, facilitators should review information obtained during initial conversations so that a productive and efficient planning meeting can take place. Similarities and differences in perspectives should be identified and organized so that at the meeting team members can be assured that their concerns have been heard, thus necessitating less time to reach consensus. School-wide PBIS leadership teams and behavior support planning meetings function in a similar way. Develop Comprehensive Plans. Like the features of functional-based behavior support plans, effective wraparound plans include uniquely designed supports, services, and interventions for the student and other members of the wraparound team. These plans are designed to address a broad range of needs that may include access to clothes or transportation, supports for caregivers (e.g., respite, assis- DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. 10, NO. 3 177 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 178 tance with obtaining a job), peer supports to enhance friendships, specialized academic instruction, and function-based behavior support plans or clinical interventions. Effective wraparound plans include strategies that (a) modify the physical context (e.g., schedules, routines, supervision); (b) support skill development (i.e., instructional strategies designed to teach, practice, and reinforce adaptive skills and behaviors; (c) enhance and build on student strengths; (d) improve access to resources; (e) enhance processes for handling information and problem solving; and (f) enhance team members’ capacity to anticipate, prevent, and respond to safety needs and emergency situations. Adhere to the Value Base During Implementation. Wraparound is grounded in a set of values that include family voice and choice, unconditional commitment, flexibility, and cultural competence (Burns & Goldman, 1999; VanDenBerg & Grealish, 1996). These are similar to the person-centered values Carr and his colleagues (2002) described as related to the applied science of positive behavior supports. The team involved in a wraparound process adheres to this humanistic value base by listening to the individuals who are most involved in the lives of the student without assigning blame and by building new partnerships that are effective, efficient, and relevant. This effort may require that traditional agency boundaries be remapped, preconceived notions of blame put aside, prior ways of doing business discontinued, or divergent perspectives given serious consideration. FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR PRACTICE AND RESEARCH Although the joining of the wraparound process and the PBIS approach have logical appeal and programmatic support, research evidence is needed to enhance our understanding of their implementation features and requirements. As Kauffman (1999a) stated regarding the role of science in the education of students with EBD, more research is needed before we can confidently say that the wraparound process and PBIS approach are scientifically 178 JOURNAL OF EMOTIONAL AND supported and rule-governed approaches to solving problems. Although research studies are needed to test and confirm the effectiveness and efficiency of the wraparound process, program evaluation data at national, state, and local levels offer strong indications that wraparound is a promising process, and guidelines for effective implementation, training, and evaluation are surfacing (Burchard et al., 1993; Burns & Goldman, 1999; Burns et al., 2000; Eber, 1996, 1998; Stroul, 1993). The PBIS approach offers a systems framework (host environment) that is designed to support the adoption and sustained use of research-validated practices (Lewis & Sugai, 1999; Sugai & Horner, 1999–2000) for all students, but especially those with or at risk for challenging behavior. The PBIS approach provides an integration of (a) behavioral science, (b) practical, function-based interventions, (c) social values, and (d) systems perspective (Sugai et al., 1999). Like wraparound, more research is needed to confirm the effectiveness and efficiency with which PBIS provides positive behavioral support to all students in a school. Supporting the integration of wraparound and PBIS is easy in one regard because they share many similarities (e.g., individualized behavior support planning for students and their families; use of effective academic and social behavior interventions; team-based planning and problem solving; a proactive, outcomedriven perspective). In addition, wraparound and PBIS are most effective when used together. Wraparound offers an emphasis on coordinated interagency supports and services, family voice, and blended perspectives. The PBIS approach contributes a functional assessment– based approach to behavior support planning, a school-wide implementation of positive behavior support, and a databased emphasis to intervention monitoring and evaluation. Empirical support for the integration of these two still is needed to improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and relevance of supports and services provided to students with or at risk for EBD and their families. Future research efforts must answer a number of important questions. First, alB E H AV I O R A L DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. though we know which practices for educating students with EBD are research supported and most likely to have a positive effect (Peacock Hill Working Group, 1991; Walker, Colvin, & Ramsey, 1995), we do not have a clear understanding as to why schools often do not adopt and sustain their use (Latham, 1988; Walker et al., 1996). Second, a systems approach clearly is required to ensure the sustained adoption and use of effective practices; however, the precise nature of the features that compose effective and efficient systems has not been verified scientifically. Again, the PBIS approach offers a useful place for defining the features of a systems approach. Third, although we know that a proactive, instructional approach is preferred, we do not understand why schools maintain an overreliance on negative interactions, exclusion, and punishment to address antisocial behavior (Nelson, 1997; Shores & Wehby, 1999; Simpson, 1999). We need to identify which factors cause educators to adopt ineffective practices, why a concerted focus on prevention is difficult to achieve (Kauffman, 1999b; Scott & Nelson, 1999a; Walker et al., 1996), and what needs to be done to ensure consistent use of effective interventions. Finally, we do not understand why collaborative systems of care that have been initiated by mental health and child welfare systems have been slow to include schools as equal partners (Eber, 1998; Eber & Nelson, 1997; Lourie, 1994). In this case, the unit of analysis is not students but the adults who are members of these systems of care. About the Authors LUCILLE EBER, EdD, is currently the statewide coordinator of the Illinois Emotional and Behavioral Disabilities (EBD) and Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports Network. Her areas of interest and expertise include program development, evaluation, and training and technical assistance on systemic application of wraparound and PBIS in schools. GEORGE SUGAI, PhD, is a professor of special education in the College of Education at the University of Oregon. He is currently co-director of the Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports at the university. His areas of expertise include be10, NO. 3 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 179 havior management, school-wide discipline and positive behavior support, functional assessment–based behavior support planning, and education of students with EBD. CARL R. SMITH, PhD, is on the faculty at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, and is director of the Resource Center for Issues in Special Education. His work has primarily focused on policy and legal issues affecting students with behavioral disorders. TERRANCE M. SCOTT, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Special Education at the University of Florida in Gainesville. His research interests include logical and realistic applications of school-wide behavior support systems, functional assessment, and behavior intervention planning. Address: Lucille Eber, ISBE EBD/PBIS Network, 160 Ridgewood Ave., #121, Riverside, IL 60546; e-mail: lewrapil@aol.com Authors’ Note The preparation of this article was supported in part by the Center on Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (U.S. Department of Education Grant H326S980003). Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Education, and such endorsements should not be inferred. References Bruns, E., Burchard, J., & Yoe, J. (1995). Evaluating the Vermont system of care: Outcomes associated with community-based wraparound services. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 4, 321–339. Burchard, J., Burchard, S., Sewell, C., & VanDenBerg, J. (1993). One kid at a time: Evaluative case studies and description of the Alaska initiative demonstration project. Juneau: State of Alaska Division of Mental Health and Mental Retardation. Burns, B. J., & Goldman, S. K. (Eds.). (1999). Promising practices in wraparound for children with serious emotional disturbance and their families (1998 Series, Vol. 4). Washington, DC: Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice, American Institute for Research. Burns, B. J., Schoenwald, S. K., Burchard, J. D., Faw, L., & Santos, A. B. (2000). Comprehensive community-based interventions for youth with severe emotional disorders: Multisystemic therapy and the wraparound process. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9, 283–314. JOURNAL OF Carr, E. G., Dunlap, G., Horner, R. H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A. P., Sailor, W., et al. (2002). Positive behavior supports: Evolution of an applied science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4, 4–16. Carson, R. R., Sitlington, P. L., & Frank, A. R. (1995). Young adulthood for individuals with behavioral disorders: What does it hold? Behavioral Disorders, 20, 127–135. Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorders. (1998). School discipline. (Available from National Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorders, 8181 Professional Place, Suite 201, Landover, MD 20785) Coalition for Juvenile Justice. (2000). Handle with care: Serving the mental health needs of young offenders. Washington, DC: Coalition for Juvenile Justice. Colvin, G., Kameenui, E. J., & Sugai, G. (1993). School-wide and classroom management: Reconceptualizing the integration and management of students with behavior problems in general education. Education and Treatment of Children, 16, 361–381. Council for Exceptional Children. (1999, Winter). Positive behavioral support. Research Connections in Special Education, No. 4, pp. 1–8. Eber, L. (1996). Restructuring schools through wraparound approach: The LADSE experience. In R. J. Illback & C. M. Nelson (Eds.), School-based services for students with emotional and behavioral disorders (pp. 139–154). Binghamton, NY: Haworth. Eber, L. (1997). Improving school-based behavioral interventions through use of the wraparound process. Journal of Reaching Today’s Youth, 1(2), 32–36. Eber, L. (1998). What’s happening in the schools? Education’s experience with systems of care. Washington, DC: Washington Business Group on Health. Eber, L. (1999). Family voice, teacher voice: Finding common ground through the wraparound process. Claiming Children. (Available from The Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health, Alexandria, VA.) Eber, L., & Nelson, C. M. (1997). Integrating services for students with emotional and behavioral needs through school-based wraparound planning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67, 385–395. Eber, L., Nelson, C. M., & Miles, P. (1997). School-based wraparound for students with emotional and behavioral challenges. Exceptional Children, 63, 539–555. Eber, L., Rolf, K., & Schreiber, M. P. (1996). A look at the 5-year ISBE EBD Initiative: End of the year report for 1995–96. LaEMOTIONAL AND B E H AV I O R A L Grange, IL: LaGrange Area Department of Special Education. Hienemann, M., & Dunlap. G. (2001). Factors affecting the outcomes of community-based behavioral support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 3, 75–82. Hoagwood, K. (1997). The Fort Bragg experiment: A comparative success or failure? American Psychologist, 52, 546–550. Horner, R., & Sugai, G. (1999). Discipline and behavioral support: Practices, pitfalls and promises. Effective School Practices, 17(4), 10–22. Iowa Department of Education. (1998). Definitions and essential elements: Student discipline provisions of the Individuals with Disabilities Act of 1997. Des Moines: Author. Kauffman, J. M. (1999a). The role of science in behavior disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 24, 265–272. Kauffman, J. M. (1999b). How we prevent the prevention of emotional and behavioral disorders. Exceptional Children, 65, 448–468. Kerr, M. M., & Nelson, C. M. (1998 ). Strategies for managing behavior problems in the classroom (3rd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill. Knitzer, J., Steinberg, Z., & Fleisch, B. (1990). At the schoolhouse door. New York: Bank Street College of Education. Knoster, T., Villa, R., & Thousand, J. (2000). A framework for thinking about systems change. In R. Villa & J. Thousand (Eds.), Restructuring for caring and effective education: Piecing the puzzle together (pp. 93– 128). Baltimore: Brookes. Koyanagi, C., & Gaines, S. (1993). All systems failure: An examination of the results of neglecting the needs of children with serious emotional disturbance. Washington, DC: National Institute for Mental Health and the Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health. Latham, G. (1988). The birth and death cycles of educational innovations. Principal, 68(1), 41–43. Lewis, T. J., & Sugai, G. (1999). Effective behavior support: A systems approach to proactive schoolwide management. Focus on Exceptional Children, 31(6), 1–24. Lourie, I. (1994). Principles of local system development for children, adolescents, and their families. Chicago: Kaleidoscope. Maag, J. W., & Katsiyannis, A. (1996). Counseling as a related service for students with emotional or behavioral disorders: Issues and recommendations. Behavioral Disorders, 21, 293–305. DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. 10, NO. 3 179 jebd-v10n3-p171 7/31/02 4:08 PM Page 180 Malloy, J., Cheney, D., & Cormier, G. (1998). Interagency collaboration and the transition to adulthood for students with emotional or behavioral disabilities. Education and Treatment of Children, 1, 303–320. Nelson, C. M. (1997). Aggressive and violent behavior: A personal perspective. Education and Treatment of Children, 20, 250– 262. Nelson, C. M., & Pearson, C. A. (1994). Juvenile delinquency in the context of culture and community. In R. L. Peterson & S. IshiiJordan (Eds.), Cultural and community contexts for emotional or behavioral disorders (pp. 78–90). Boston: Brookline Press. Peacock Hill Working Group. (1991). Problems and promises in special education and related services for children and youth with emotional or behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 16, 299–313. Schorr, L. B., & Julius, W. (1998). Common purpose: Strengthening families and neighborhoods to rebuild America. New York: Anchor/Doubleday. Scott, T. M., & Nelson, C. M. (1999a). Functional behavioral assessment: Implications for training and staff development. Behavioral Disorders, 24, 249–252. Scott, T. M., & Nelson, C. M. (1999b). Universal school discipline strategies: Facilitating learning environments. Effective School Practices, 17(4), 54–64. Shores, R. E., & Wehby, J. H. (1999). Analyzing the classroom and social behavior of students with EBD. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 7, 194–199. Simpson, R. (1999). Children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders: A concerned look at the present and a hopeful eye for the future. Behavioral Disorders, 24, 284–292. Skiba, R. J., & Peterson, R. L. (2000). School discipline at a crossroads: From zero tolerance to early response. Exceptional Children, 66, 335–347. Smith, C. (2000). Behavioral and discipline provisions of IDEA ’97: Implicit compe- 180 JOURNAL OF EMOTIONAL AND tencies yet to be confirmed. Exceptional Children, 66, 403–412. Smith, S. W., & Coutinho, M. J. (1997). Achieving the goals of the national agenda: Progress and prospects. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 5, 2–5. Sprague, J., Sugai, G., & Walker, H. (1998). Antisocial behavior in schools. In S. Watson & F. Gresham (Eds.), Child behavior therapy: Ecological considerations in assessment, treatment, and evaluation (pp. 451– 474). New York: Plenum Press. Sprague, J., & Walker, H. (2000). Early identification and intervention for youth with antisocial and violent behavior. Exceptional Children, 66, 367–379. Stroul, B. A. (1993, September). Systems of care for children and adolescents with severe emotional disturbances: What are the results? Washington, DC: CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Center for Child Health and Mental Health Policy, and Georgetown University Child Development Center. Stroul, B. A., & Freidman, R. (1986). A system of care for severely emotionally disturbed children and youth. Washington, DC: CASSP Technical Assistance Center. Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (1999–2000). Including the functional behavioral assessment technology in schools. Exceptionality, 8, 145–148. Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T. J., Nelson, C. M., et al. (2000). Applying positive behavioral support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support, 2, 131–143. Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., & Sprague, J. (1999). Functional assessment-based behavior support planning: Research-topractice-to-research. Behavioral Disorders, 24, 223–227. Sugai, G., Lewis-Palmer, T., & Hagan-Burke, S. (1999–2000). Overview of the functional behavioral assessment process. Exceptionality, 8, 149–160. B E H AV I O R A L DISORDERS, FALL 2002, VOL. Sugai, G., Sprague, J. R., Horner, R. H., & Walker, H. M. (2000). Preventing school violence: The use of office referrals to assess and monitor school-wide discipline interventions. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8, 94–101. Todd, A., Horner, R., Sugai, G., & Colvin, G. (1999). Individualizing school-wide discipline for students with chronic problem behaviors: A team approach. Effective School Practices, 17(4), 72–82. Turnbull, H. R., Wilcox, B. L., Stowe, M., & Turnbull, A. P. (2001). IDEA requirements for use of PBS: Guidelines for responsible agencies. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 3, 3–10. U.S. Department of Education. (1998). Twentieth annual report to Congress on the implementation of IDEA: The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC: USGPO. VanDenBerg, J. E., & Grealish, E. M. (1996). Individualized services and supports through the wraparound process: Philosophy and procedures. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 5 (1), 7–21. Walker, H., Colvin, G., & Ramsey, E. (1995). Antisocial behavior in public schools: Strategies & best practices. Pacific Grove, CA: Brookes/Cole. Walker, H. M., Horner, R.H., Sugai, G., Bullis, M., Sprague, J. R., Bricker, D., & Kaufmann, M. J. (1996). Integrated approaches to preventing antisocial behavior patterns among school-aged children and youth. Journal of Emotional and Behavior Disorders, 4, 194–209. Walker, H. M., & Sprague, J. R. (1999). Longitudinal research and functional behavior assessment issues. Behavioral Disorders, 24, 335–337. Zins, J. E., & Ponti, C. R. (1990). Best practices in school-based consultation. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 673–694). Washington, DC: National Association of School Psychologists. 10, NO. 3 Copyright of Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders is the property of Sage Publications Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.