GAO FOREIGN ASSISTANCE U.S. Democracy

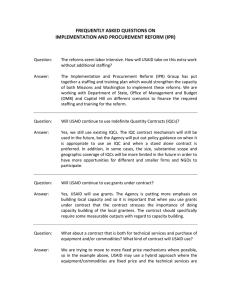

advertisement