Crises of Rule: Insurrectionary Geographies and the Impacts of War

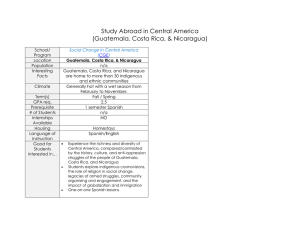

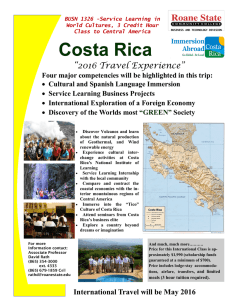

advertisement