Research

Original Investigation

Effect of a Clinical Practice Guideline for Pediatric

Complicated Appendicitis

Zachary I. Willis, MD; Eileen M. Duggan, MD, MPH; Brian T. Bucher, MD; John B. Pietsch, MD;

Monica Milovancev, MSN, CPNP; Whitney Wharton, MSN, CPNP; Jessica Gillon, PharmD, BCPS;

Harold N. Lovvorn III, MD; James A. O’Neill Jr, MD; M. Cecilia Di Pentima, MD, MPH; Martin L. Blakely, MD, MS

Invited Commentary

IMPORTANCE Complicated appendicitis is a common condition in children that causes

substantial morbidity. Significant variation in practice exists within and between centers. We

observed highly variable practices within our hospital and hypothesized that a clinical

practice guideline (CPG) would standardize care and be associated with improved patient

outcomes.

Supplemental content at

jamasurgery.com

OBJECTIVE To determine whether a CPG for complicated appendicitis could be associated

with improved clinical outcomes.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A comprehensive CPG was developed for all children

with complicated appendicitis at Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, a

freestanding children’s hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, and was implemented in July 2013.

All patients with complicated appendicitis who were treated with early appendectomy during

the study period were included in the study. Patients were divided into 2 cohorts, based on

whether they were treated before or after CPG implementation. Clinical characteristics and

outcomes were recorded for 30 months prior to and 16 months following CPG

implementation.

EXPOSURE Clinical practice guideline developed for all children with complicated appendicitis

at Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The primary outcome measure was the occurrence of any

adverse event such as readmission or surgical site infection. In addition, resource use,

practice variation, and CPG adherence were assessed.

RESULTS Of the 313 patients included in the study, 183 were boys (58.5%) and 234 were

white (74.8%). Complete CPG adherence occurred in 78.7% of cases (n = 96). The pre-CPG

group included 191 patients with a mean (SD) age of 8.8 (4.0) years, and the post-CPG group

included 122 patients with a mean (SD) age of 8.7 (4.1) years. Compared with the pre-CPG

group, patients in the post-CPG group were less likely to receive a peripherally inserted

central catheter (2.5%, n = 3 vs 30.4%, n = 58; P < .001) or require a postoperative computed

tomographic scan (13.1%, n = 16 vs 29.3%, n = 56; P = .001), and length of hospital stay was

significantly reduced (4.6 days post-CPG vs 5.1 days pre-CPG, P < .05). Patients in the

post-CPG group were less likely to have a surgical site infection (relative risk [RR], 0.41; 95%

CI, 0.27-0.74) or require a second operation (RR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.12-1.00). In the pre-CPG

group, 30.9% of patients (n = 59) experienced any adverse event, while 22.1% of post-CPG

patients (n = 27) experienced any adverse event (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.48-1.06).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Significant practice variation exists among surgeons in the

management of pediatric complicated appendicitis. In our institution, a CPG that

standardized practice patterns was associated with reduced resource use and improved

patient outcomes. Most surgeons had very high compliance with the CPG.

JAMA Surg. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0194

Published online March 30, 2016.

Author Affiliations: Department of

Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University

School of Medicine, Nashville,

Tennessee (Willis); Department of

Pediatric Surgery, Vanderbilt

University School of Medicine,

Nashville, Tennessee (Duggan,

Bucher, Pietsch, Milovancev,

Wharton, Lovvorn, O’Neill,

Di Pentima, Blakely); Division of

Pediatric Surgery, University of Utah,

Salt Lake City (Bucher); Monroe

Carell, Jr. Children’s Hospital at

Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tennessee

(Gillon).

Corresponding Author: Martin L.

Blakely, MD, MS, Monroe Carell Jr

Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt,

2200 Children's Way, Ste 7100,

Nashville, TN 37232 (martin.blakely

@vanderbilt.edu).

(Reprinted) E1

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/ by a Vanderbilt University User on 04/01/2016

Research Original Investigation

A Clinical Guideline for Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis

A

ppendicitis is a common surgical condition, with a cumulative lifetime incidence of 9%.1 Children experience

the greatest risk of disease, and incidence among children is 4 times greater than the overall population. Appendicitis is often categorized as uncomplicated or complicated, with

the latter referring to a gangrenous or perforated appendix and

characterized by greater morbidity.2 Children, particularly those

younger than 15 years, are at very high risk of perforated appendicitis compared with young adults.1 The Healthcare Cost and

Utilization Project3 estimates that appendicitis with peritonitis accounted for 25 410 pediatric hospital admissions in 2012,

with a mean length of stay of 5.2 days and mean costs of $13 076.

Appendicitis is a common and costly condition,4 but the care

of children with appendicitis is highly variable.5 Complicated

appendicitis is associated with substantial postoperative morbidity. Nationwide, the readmission rate following appendectomy for complicated appendicitis is estimated at 12.8%.6 Clinical trials have consistently found a postoperative intra-abdominal

abscess rate of approximately 20% in cases of perforated appppendicitis.7,8 Other adverse events, such as superficial surgical

site infections (SSIs)and small-bowel obstruction, occur less frequently. These adverse events result in substantially increased

costs,6,9 additional exposure to ionizing radiation, additional operative interventions, prolonged antibiotic exposure, and delay

in return to premorbid function.

The appropriate management of children with complicated appendicitis has been the subject of substantial research, focusing on aspects including diagnosis, timing of surgery, surgical approach, preoperative and postoperative

antibiotic management, and discharge criteria. Still, many questions remain about optimal management in all phases.10-12 A

2004 survey of pediatric surgeons revealed considerable variation in the management of appendicitis.12

Medical conditions that are common, costly, and characterized by substantial variation in care are ideal targets for quality improvement via standardization of care. 4 Pediatric

appendicitis has been the subject of effective qualityimprovement initiatives that have reduced the use of computed tomographic (CT) scans for diagnosis13 and standardized the overall care of complicated appendicitis.14 In the

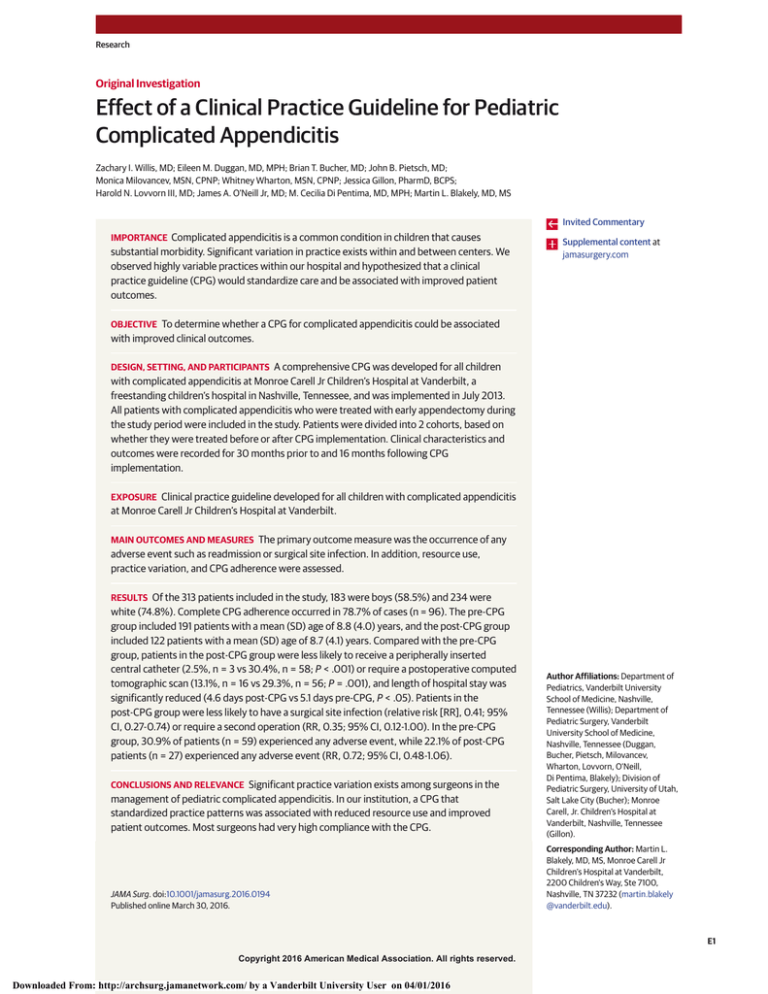

Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, we identified significant variability in the management of complicated

appendicitis along with high rates of intra-abdominal abscess formation and readmission. Therefore, we designed a

clinical practice guideline (CPG) with the goal of standardizing the operative and postoperative management of complicated appendicitis (Figure). The CPG was developed with multidisciplinary input from all services involved in these patients’

care as recommended by the Institute of Medicine.15 We hypothesized that CPG implementation would result in reduced health care use and fewer overall adverse events.

Methods

Question Can a clinical practice guideline for pediatric

complicated appendicitis achieve improvements in health care use

and patient outcomes?

Findings In this study comparing clinical outcomes before and

after implmentation of a clinical practice guideline for the

management of pediatric complicated appendicitis, there were

statistically significant declines in the incidence of postoperative

intra-abdominal abscess and the incidence of additional operative

procedures after guideline implementation. Resource use (eg,

hospital length of stay and peripherally inserted central catheter

use) also improved with clinical practice guideline–directed care.

Meaning The use of a clinical practice guideline for pediatric

complicated appendicitis can result in meaningful improvements

in patient outcomes.

nessee. Prior to guideline development, an internal review of

the management and outcomes of complicated appendicitis

revealed substantial practice variation and high rates of postoperative intra-abdominal abscess and readmission. Therefore, a CPG was proposed with the goals of standardizing practice and improving outcomes. The CPG was developed with

input from pediatric surgeons and pediatric surgery nurse practitioners, residents, and clinic nurses. The development team

also consulted with specialists from radiology; infectious

diseases; emergency medicine; and gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. The final CPG was implemented on July

1, 2013.

The CPG applies to all patients with complicated appendicitis, defined as the operative finding of a gangrenous or perforated appendix. The CPG encourages early rather than interval appendectomy (Figure).16,17 For patients in whom an

abscess is discovered at operation, placement of a closedsuction drain is encouraged. All patients are administered piperacillin-tazobactam before and after the operation,18 with

transition to a 7-day course of oral ciprofloxacin and metronidazole when tolerating a diet. A white blood cell (WBC) count

is not checked to determine the duration of antibiotic therapy

or hospitalization. A follow-up clinic visit is scheduled within

2 weeks. For patients with ongoing fever, diarrhea, or intolerance of oral intake, along with physical examination findings

suspicious for intra-abdominal abscess, a CT scan is obtained

on the seventh postoperative day. If an abscess is discovered,

the patient may undergo operative or percutaneous drainage

or ongoing medical management as clinically indicated at the

discretion of the treating surgeon.

To allow individual surgeons to assess their performance, all pediatric surgeons received monthly reports detailing overall and individual CPG adherence. Small incentives in the form of gift cards were awarded to the monthly top

performer.

Patients and Data Collection

CPG Development

Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt is a 271bed, freestanding, tertiary referral center in Nashville, TenE2

Key Points

From July 1, 2013, the date of CPG implementation, until November 1, 2014, all patients treated for complicated appendicitis in Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt were

JAMA Surgery Published online March 30, 2016 (Reprinted)

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/ by a Vanderbilt University User on 04/01/2016

jamasurgery.com

A Clinical Guideline for Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis

Original Investigation Research

Figure. Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) Used for Suspected and Confirmed Complicated Appendicitis

Patient characteristics

increasing likelihood of

gangrenous or perforated

appendicitis: young age,

>48 h of symptoms,

generalized tenderness on

abdominal examination,

white blood cell count

>19 400 μL, and abscess

identification by imaging

Not improving/responding

Continued fever, examination

not improving, diarrhea, or

otherwise worsening condition,

consider nutrition consult

No

Order

piperacillin-tazobactam.

If penicillin allergy:

ciprofloxacin/flagyl

Early laparoscopic appendectomy

• Local irrigation (500-1000 mL)

• Blake drain if abscess or

widespread contamination

Consider computed tomography of

abdomen/pelvis POD7 if concern for

intra-abdominal abscess

Responding

to treatment?

Interventional

radiology

request consult

Yes

Inclusion criteria

Children with gangrenous or perforated appendicitis

determined intraoperatively by the attending surgeon.

In children with very delayed presentation (>1 wk)

who are nontoxic and have a contained abscess

on imaging, consideration should be given to treatment

with interval appendectomy (with/without initial

drainage of the intra-abdominal abscess) rather than

using this CPG.

Yes

Intraabdominal

abscess?

No

Evaluate for

other infection

source

Interventional radiology

or operative drainage of

intra-abdominal abscess;

obtain culture

Consider oral

ciprofloxacin/flagyl

when taking regular diet

Meets discharge criteria

Discharge criteria

Afebrile (<38°C) >24 h

Tolerating diet

Adequate pain control with oral medications

Benign abdominal examination by attending surgeon

Ambulating without assistance

Discharge home with

ciprofloxacin/flagyl 7 d

Follow-up 1 wk,

if unable to follow up,

telephone call

POD7 indicates postoperative day 7. To convert white blood cell count to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001.

prospectively added to a study-specific REDCap database.19

To determine baseline patient outcomes, resource use, and

practice variation, a cohort of patients treated for complicated appendicitis in the 30 months prior to CPG implementation (January 1, 2011, to June 30, 3013) was created. All

records in that time with an International Classification of

Diseases, Ninth Edition diagnosis code of 540.0 (acute

appendicitis with generalized peritonitis) or 540.1 (acute

appendicitis with peritoneal abscess) were ascertained.

Cases were excluded at this stage if there was no mention of

appendiceal perforation or gangrenous appendicitis in the

operative report or surgeon’s progress notes. For both the

pre- and post-CPG patients, medical records were reviewed,

and demographic and clinical data were extracted into

the database. Only patients who were treated by early

appendectomy (occurring during the index admission for

appendicitis) were included in this analysis. Because of the

subjective nature of the diagnosis of gangrenous appendicitis, these patients were also excluded from the primary

analysis (n = 34), leaving only patients with a grossly perforated appendix or gross peritoneal contamination. Because

the CPG did apply to patients with gangrenous appendicitis,

a secondary analysis was conducted that included these

patients. The study was approved by the institutional

review board of the Vanderbilt University School of Medijamasurgery.com

cine. The institutional review board determined it to be a

quality improvement project with no consent required.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the occurrence of any adverse event within 30 days of appendectomy. Adverse events

assessed included SSIs, classified as superficial incisional, deep

incisional, or organ/space infection20; emergency department

visits; hospital readmissions; additional operative procedure;

any interventional radiology procedure; and adverse effects of

antibiotics requiring discontinuation and/or medical treatment.

Health care use measures included length of stay, proportion of

patients undergoing interval appendectomy, proportion undergoing open appendectomy, proportion receiving a postoperative CT scan, proportion receiving a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC), proportion having a WBC count checked to

determine duration of antibiotic administration, and proportion

receiving parenteral nutrition. The CPG strongly discouraged use

of PICC unless indicated for parenteral nutrition. Initial diagnostic evaluation was not addressed by the CPG, but the proportion

of patients receiving a preoperative CT scan was gathered to assess baseline trends in CT use.

To assess CPG adherence, we calculated the adherence rate

for each individual surgeon and tabulated the most common

reasons for nonadherence. To be considered CPG-adherent, an

(Reprinted) JAMA Surgery Published online March 30, 2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/ by a Vanderbilt University User on 04/01/2016

E3

Research Original Investigation

A Clinical Guideline for Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics, Clinical Data at the Time of Presentation, Imaging Use and Findings,

and Operative Findingsa

Pre-CPG

(n = 191)

Characteristic

Age, mean (SD), y

Male, No. (%)

Post-CPG

(n = 122)

P Value

8.8 (4.0)

8.7 (4.1)

.79

111 (58.1)

72 (59.0)

.88

Race, No. (%)

American Indian or Alaska Native

1 (0.5)

1 (0.8)

Asian

3 (1.6)

4 (3.3)

Black or African American

23 (12.0)

8 (6.6)

141 (73.8)

93 (76.2)

23 (12.0)

16 (13.1)

44 (23.0)

28 (23.0)

.99

Duration of symptoms, h

76.6 (65.1)

67.6 (47.8)

.16

White blood cell count, /μL

17.2 (6.4)

17.8 (6.0)

.41

White

Unknown/not reported

.43

Ethnicity, No. (%)

Hispanic

Presenting characteristics, mean (SD)

No. of patients

183

117

Preoperative imaging, No. (%)

CT

128 (67.0)

63 (48.4)

.001

Ultrasonography

79 (41.4)

79 (64.8)

<.001

None

10 (5.2)

1 (0.8)

.04

11.3 (7.2)

.26

Operative management, mean (SD), h

Time from presentation to OR

10.2 (10.1)

No. of patients

190

119

167 (87.4)

105 (86.1)

Open

11 (5.8)

8 (6.6)

Laparoscopic converted to open, No. (%)

13 (6.8)

9 (7.4)

.92

79 (41.4)

53 (43.4)

.72

Laparoscopic, No. (%)

Abscess identified at operation

individual patient had to meet the following criteria: (1) received only appropriate inpatient antibiotics (piperacillintazobactam or ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole if allergic to

penicillin); (2) did not have a WBC count checked to determine duration of antibiotics or readiness for discharge; (3) prescribed ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole for 7 days at discharge; and (4) attended a follow-up surgery clinic appointment

within 30 days of discharge. Responsibility for nonadherence

was assigned to the medical team or family. For example, if no

follow-up appointment was scheduled, then responsibility for

nonadherence was assigned to the surgical team. If a patient

failed to attend a scheduled follow-up appointment, responsibility was assigned to the family. To determine the effect of

the CPG on practice variation, between-surgeon use of PICCs,

parenteral nutrition, and WBC count to determine discharge

eligibility was tabulated.

Data Analysis

Dichotomous measures were assessed with χ2 test and Fisher

exact test as appropriate. For dichotomous outcome measures, relative risk (RR) with 95% CI was calculated with the

pre-CPG group as the referent. For continuous measures and

outcomes, a t test was used when data were normally distributed. When data were not normally distributed, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. All tests were 2-tailed, with a P

value less than .05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using Stata/IC 13.1 (StataCorp).

E4

Abbreviations: CPG, clinical practice

guideline; CT, computed tomography;

OR, operating room.

SI conversion factor: to convert white

blood cell count to × 109 per liter,

multiply by .001.

a

Excluding patients diagnosed as

having appendicitis more than

48 hours after admission (n = 4).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Presenting Characteristics

Of 219 patients assessed for inclusion in the pre-CPG cohort,

19 were excluded because of interval appendectomy and 9 were

excluded for nonperforated appendicitis, for a final pre-CPG

cohort of 191 patients. One hundred fifty-two patients were assessed for inclusion in the post-CPG cohort, after excluding 5

because of interval appendectomy and 25 because of nonperforated appendicitis, for a final post-CPG group of 122

patients.

Data regarding patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were no significant

differences in the age (P = .79), sex (P = .88), race (P = .43), or

Hispanic ethnicity (P = .99) between patients in the pre-CPG

and post-CPG groups. There were no significant differences in

preoperative duration of symptoms (P = .16) or WBC count

(P = .41) on admission. There was no difference in the proportion of patients diagnosed as having an intra-abdominal abscess at the time of appendectomy (P = .72).

Preoperative Imaging and Operative Management

Preoperative and operative management are summarized in

Table 1. There was no difference in operative approach between the 2 cohorts, with most patients in both groups undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy (P = .94). There was a sig-

JAMA Surgery Published online March 30, 2016 (Reprinted)

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/ by a Vanderbilt University User on 04/01/2016

jamasurgery.com

A Clinical Guideline for Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis

Original Investigation Research

nificant difference in the use of preoperative imaging, with

67% of pre-CPG patients undergoing a CT scan vs 48% of postCPG patients (P = .001). Conversely, 41.4% of pre-CPG

patients had preoperative ultrasonography vs 64.8% of postCPG patients (P < .001).

A total of 10 individual surgeons operated in cases of

complicated appendicitis during the study. Three surgeons performed a total of 40 appendectomies for complicated appendicitis exclusively in the pre-CPG period, while 1 surgeon

performed 1 appendectomy for complicated appendicitis exclusively in the post-CPG period. The remaining 6 surgeons performed a minimum of 9 appendectomies for complicated

appendicitis in both the pre- and post-CPG periods.

CPG Adherence and Standardization of Practice

Of the 122 patients in the post-CPG group, complete CPG adherence occurred in 96 patients (78.7%). Twenty-nine deviations from protocol occurred in 26 patients, with the most common reason being failure to follow up in pediatric surgery clinic

(n = 12) and failure to prescribe 7 days of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole (n = 10). Thirteen of 29 deviations (45%) were attributed to the health care team; the remainder were attributed to the family, most commonly for failure to attend the

scheduled follow-up appointment. When considering only adherence failures attributed to health care teams, overall adherence was 87.5%. For the 6 surgeons treating patients after

CPG implementation, adherence ranged from 67% to 100%

(Table 2). There were no temporal trends in adherence during

the 16 months of observation.

Substantial variation in practice was observed before CPG

implementation. Prior to CPG implementation, individual sur-

Table 2. Clinical Practice Guidelines Adherence by Operating Surgeon

Surgeon

19

18 (94.7)

2

18

12 (66.7)

3

17

13 (76.5)

4

23

22 (95.7)

5

22

21 (95.5)

6

1

1 (100)

7

9

9 (100)

109

96 (88.1)

Total

a

Adherence, No. (%)a

No. of Cases

1

Cases in which the family was nonadherent are excluded (n = 13).

geons’ use of PICCs ranged from 7% to 48%; after CPG implementation, no operating surgeon ordered placement of more

than 1 PICCs (range, 0%-5%). Parenteral nutrition use ranged

from 6% to 22% before implementation and from 0% to 5%

after implementation. Before the CPG, individual surgeons’ use

of the WBC count to determine eligibility for discharge ranged

from 7% to 100%; following implementation, the range was

0% to 11%. The intersurgeon distribution of surgical approach was similar between the cohorts: the use of an open

approach ranged from 0% to 17% for both cohorts.

Postoperative Resource Use

Inpatient use of hospital services and procedures was lower

in the post-CPG group (Table 3). Specifically, in the pre-CPG

group, 84 patients (44%) had a WBC count drawn prior to discharge compared with 5 (4.1%, P < .001) in the post-CPG group.

Fifty-eight patients (30.4%) in the pre-CPG group and 3 patients (2.5%) in the post-CPG group (P < .001) underwent PICC

placement. Twenty-three patients (12.0%) in the pre-CPG group

underwent an interventional radiology procedure compared

with 3 (2.5%) in the post-CPG group (P = .003). Parenteral nutrition was administered to 22 patients (11.5%) in the pre-CPG

group and to 2 patients (1.6%) in the post-CPG group (P = .001).

In the pre-CPG group, 56 patients (29.3%) underwent a postoperative CT scan, compared with 16 (13.1%) in the post-CPG

group (P = .001).

Patient Outcomes

The proportions of patients experiencing adverse events between the 2 groups are presented in Table 4. In the pre-CPG

group, 59 patients (30.9%) experienced any adverse event,

while 27 post-CPG patients (22.1%) experienced any adverse

event (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.48-1.06). In the pre-CPG group, 27

patients (14.1%) returned to the emergency department within

30 days of appendectomy, while 14 post-CPG patients (11.5%)

returned to the emergency department (RR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.441.49). The 30-day readmission rate was 16.2% in the pre-CPG

group and 11.5% in the post-CPG group (RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.391.27). Prior to CPG implementation, 9.4% of patients returned

to the operating room, while 3.3% of post-CPG patients required

a second surgical procedure (RR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.12-1.00). There

was a significant decrease in the proportion of patients who had

an organ-space SSI, from 24.1% in the pre-CPG group to 9.8%

in the post-CPG group (RR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.23-0.74). Superficial incisional and deep incisional SSIs were uncommon and no

Table 3. Resource Use by CPG Status

No. (%)

Resource

Pre-CPG

(n = 191)

Post-CPG

(n = 122)

WBC count prior to discharge

84 (44)

5 (4.1)

0.09 (0.05-0.17)

<.001

PICC at any time

58 (30.4)

3 (2.5)

0.08 (0.04-0.18)

<.001

Any IR procedure

23 (12.0)

3 (2.5)

0.20 (0.07-0.58)

.003

Receipt of parenteral nutrition

22 (11.5)

2 (1.6)

0.14 (0.04-0.47)

.001

56 (29.3)

16 (13.1)

0.45 (0.28-0.72)

.001

8 (4.2)

1 (0.8)

0.20 (0.02-1.54)

.10

P Value

RR (95% CI)

Postoperative

CT

Ultrasonography

jamasurgery.com

Abbreviations: CPG, clinical practice

guideline; CT, computed tomography;

IR, interventional radiology;

PICC, peripherally inserted central

catheter; RR, relative risk;

WBC, white blood cell.

(Reprinted) JAMA Surgery Published online March 30, 2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/ by a Vanderbilt University User on 04/01/2016

E5

Research Original Investigation

A Clinical Guideline for Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis

Table 4. Patient Outcomes

No. (%)

Outcome

Postoperative length of stay, median, d

Pre-CPG

(n = 191)

5.1

Post-CPG

(n = 122)

4.6

RR (95% CI)

NA

P Value

.03

Any adverse event

59 (30.9)

27 (22.1)

0.72 (0.48-1.06)

.09

ED visit

27 (14.1)

14 (11.5)

0.81 (0.44-1.49)

.50

Readmission

31 (16.2)

14 (11.5)

0.71 (0.39-1.27)

.24

Return to OR

18 (9.4)

4 (3.3)

0.35 (0.12-1.00)

.04

46 (24.1)

12 (9.8)

0.41 (0.23-0.74)

4 (2.1)

2 (1.6)

0.78 (0.15-4.21)

SSI

Organ-space (intra-abdominal abscess)

Incisional (superficial or deep)

different between the groups. Postoperative length of stay was

significantly shorter in the post-CPG cohort (median of 5.1 days

vs 4.6 days, P < .05). For patients with an intra-abdominal abscess at the time of appendectomy, the median postoperative

length of stay was 5.8 days in the pre-CPG cohort vs 4.9 days

in the post-CPG cohort (P < .05).

Results of a secondary analysis of patient outcomes, in

which patients with gangrenous appendicitis were included,

are displayed in the eTable in the Supplement. There were 9

such patients in the pre-CPG group and 25 such patients in the

post-CPG group (4.5% vs 17.0%, P < .001). Adverse events occurred in 2 of these patients, both in the post-CPG group.

Discussion

Implementation of a CPG for complicated appendicitis in our

institution was associated with greater standardization of

care; decreased postoperative use of CT scans, interventional

radiology procedures, and PICCs; shorter inpatient length of

stay; and lower rates of postoperative infectious complications. The high adherence rate suggests that the CPG was acceptable to pediatric surgeons, pediatric surgery nurse practitioners, residents, and clinic nurses, likely owing to the

collaborative process by which the guideline was developed.

Among the 122 patients treated after CPG implementation, there

were only 13 deviations attributed to the pediatric surgery service (10.7%).

We observed a 14.3% reduction in the absolute risk of an

organ-space SSI, translating to a number needed to treat of 7

patients to avoid one such complication. This improvement

is reflected in the observed reductions in the length of stay and

the risks of requiring an interventional radiology procedure or

a second operative procedure.

Since 2010, several research groups have reported successful efforts to reduce CT scan use in the diagnosis of pediatric appendicitis.13,21,22 In our study, the use of preoperative

CT scans was significantly lower in the post-CPG group because diagnosis relied increasingly on ultrasonography. Because diagnostic approach was not a target of the CPG, this

change is likely associated with a secular trend. More strikingly, patients treated after CPG implementation were 55% less

likely to undergo a postoperative CT scan than their predecessors, a reduction of 22 CT scans per 100 patients treated. PostE6

.002

>.99

Abbreviations: CPG, clinical practice

guideline; ED, emergency

department; NA, not applicable;

OR, operating room; RR, relative risk;

SSI, surgical site infection.

operative CT scans were not replaced by ultrasonographies as

in preoperative patients because the use of postoperative

ultrasonographies did not rise. Because the CPG specified triggers for a postoperative CT scan, the decline in CT use is

believed to be caused by improvements in patient outcomes.

Furthermore, the decrease in CT use was not accompanied by

an increase in length of stay or readmissions, suggesting that

this approach did not result in missed diagnoses of postoperative SSIs.

Similar benefit was seen with the reduction in PICC placements. Rice-Townsend et al5 found that PICC use by hospital

ranged from 1.7% to 81.8% for patients with complicated appendicitis, with a weighted average of 18.9%. Use of PICCs fell

from 30.4% to 2.5% in our cohort, a 92% reduction. While there

were no major complications related to PICCs in either group,

a 2012 study23 found that 31% of children who have a PICC

placed experience a medically attended complication. The CPG

recommends against PICC use except in unusually complicated cases such as when parenteral nutrition was required.

In the pre-CPG cohort, PICCs were placed frequently and with

highly variable frequency among attending surgeons. Following CPG implementation, PICCs were rarely placed. Similarly,

there was a broad range of practice prior to CPG implementation with regard to obtaining a WBC count to determine

duration of antibiotic therapy and/or eligibility for discharge.

In the post-CPG cohort, the WBC count was rarely checked by

any of the attending surgeons.

Our study had several limitations. There was a significantly greater proportion of patients with gangrenous appendicitis in the post-CPG era than the pre-CPG era. The reason

for this is unclear. Gangrenous appendicitis is a subjective diagnosis, and surgeons’ propensity to assign this diagnosis may

have been affected by the presence of the CPG. The diagnosis

of perforated appendicitis required gross perforation and/or

gross contamination of the peritoneal cavity with bowel contents; this diagnosis is far less subjective. To eliminate this difference in patient groups before and after the CPG implementation, gangrenous appendicitis cases were excluded from the

primary analysis. Consequently, the patient cohorts prior to

and after CPG implementation were very similar (ie, all had perforated appendicitis and were similar in other regards). There

was little difference between our primary results and the results of a secondary analysis in which patients with gangrenous appendicitis were included. Any assessment of a guide-

JAMA Surgery Published online March 30, 2016 (Reprinted)

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/ by a Vanderbilt University User on 04/01/2016

jamasurgery.com

A Clinical Guideline for Pediatric Complicated Appendicitis

line implementation is biased by time: we do not know how

management and outcomes might have changed over time

without intervention. Establishing a contemporaneous control group with such a study design was not feasible because

all clinicians were necessarily aware of the CPG. Additionally,

the failure to find a statistically significant difference on several important outcome measures was likely a consequence of

inadequate power. Finally, because several interventions were

incorporated simultaneously, it is difficult to determine which

changes had the greatest benefit.

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that a concerted effort to standardize the care of children with complicated appendicitis may substantially improve patient outcomes. Our guideline was designed to not replace the surgeon’s

judgment with respect to any individual case. For a heteroge-

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Accepted for Publication: January 19, 2016.

Published Online: March 30, 2016.

doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0194.

Author Contributions: Drs Willis and Blakely had

full access to all the data in the study and take

responsibility for the integrity of the data and the

accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Duggan, Pietsch,

Milovancev, Wharton, O’Neill, Di Pentima, Blakely.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data:

Willis, Duggan, Bucher, Pietsch, Milovancev, Gillon,

Lovvorn, Di Pentima, Blakely.

Drafting of the manuscript: Willis, Milovancev,

Blakely.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important

intellectual content: Duggan, Bulcher, Pietsch,

Wharton, Gillon, Lovvorn, O’Neill, Di Pentima,

Blakely.

Statistical analysis: Willis, Duggan, Di Pentima.

Administrative, technical, or material support:

Bucher, Milovancev, Wharton, Gillon, Lovvorn,

Di Pentima.

Study supervision: Pietsch, O’Neill, Di Pentima,

Blakely.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Funding/Support: Dr Willis was supported by

training grant T32 AI095202 from the National

Institutes of Health (principal investigator: Mark

Denison, MD).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding

organization had no role in the design and conduct

of the study; collection, management, analysis, and

interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or

approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit

the manuscript for publication.

REFERENCES

1. Anderson JE, Bickler SW, Chang DC, Talamini MA.

Examining a common disease with unknown

etiology: trends in epidemiology and surgical

management of appendicitis in California,

1995-2009. World J Surg. 2012;36(12):2787-2794.

2. Dunn J. Appendicitis. In: Coran A, ed. Pediatric

Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012:1255-1263.

3. Agency for Health Care Research and Quality.

HCUP Kids’ Inpatient Database. http://hcupnet

.ahrq.gov/. Published 2012. Accessed November

26, 2014.

jamasurgery.com

Original Investigation Research

neous condition with many open questions about optimal management, flexibility within a guideline is likely to increase its

acceptability.

Conclusions

Complicated appendicitis is an important target for quality improvement. In the absence of national management guidelines, individual institutions may develop their own guidelines based on the best available evidence, taking into account

their particular surgeons’ experience, case mix, trainee involvement, and imaging capability. A careful assessment for

local practice variation and undesirable outcomes will identify points of emphasis for institutional guidelines.

4. Keren R, Luan X, Localio R, et al; Pediatric

Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network.

Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research

topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med. 2012;166(12):1155-1164.

5. Rice-Townsend S, Barnes JN, Hall M, Baxter JL,

Rangel SJ. Variation in practice and resource

utilization associated with the diagnosis and

management of appendicitis at freestanding

children’s hospitals: implications for value-based

comparative analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):12281234.

evaluation can decrease computed tomography

utilization while maintaining diagnostic accuracy.

Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):568-573.

14. Slusher J, Bates CA, Johnson C, Williams C,

Dasgupta R, von Allmen D. Standardization and

improvement of care for pediatric patients with

perforated appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(6):

1020-1024.

15. Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice

guidelines we can trust. http://www.nap.edu/read

/13058/chapter/2#4. Accessed February 5, 2015.

6. Rice-Townsend S, Hall M, Barnes JN, Baxter JK,

Rangel SJ. Hospital readmission after management

of appendicitis at freestanding children’s hospitals:

contemporary trends and financial implications.

J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(6):1170-1176.

16. St Peter SD, Aguayo P, Fraser JD, et al. Initial

laparoscopic appendectomy versus initial

nonoperative management and interval

appendectomy for perforated appendicitis with

abscess: a prospective, randomized trial. J Pediatr

Surg. 2010;45(1):236-240.

7. Fraser JD, Aguayo P, Leys CM, et al. A complete

course of intravenous antibiotics vs a combination

of intravenous and oral antibiotics for perforated

appendicitis in children: a prospective, randomized

trial. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(6):1198-1202.

17. Blakely ML, Williams R, Dassinger MS, et al.

Early vs interval appendectomy for children with

perforated appendicitis. Arch Surg. 2011;146(6):

660-665.

8. St Peter SD, Tsao K, Spilde TL, et al. Single daily

dosing ceftriaxone and metronidazole vs standard

triple antibiotic regimen for perforated appendicitis

in children: a prospective randomized trial. J Pediatr

Surg. 2008;43(6):981-985.

18. Goldin AB, Sawin RS, Garrison MM, Zerr DM,

Christakis DA. Aminoglycoside-based

triple-antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy for

children with ruptured appendicitis. Pediatrics.

2007;119(5):905-911.

9. Myers AL, Williams RF, Giles K, et al. Hospital

cost analysis of a prospective, randomized trial of

early vs interval appendectomy for perforated

appendicitis in children. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214

(4):427-434.

19. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez

N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture

(REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and

workflow process for providing translational

research informatics support. J Biomed Inform.

2009;42(2):377-381.

10. Lee SL, Islam S, Cassidy LD, Abdullah F, Arca

MJ; 2010 American Pediatric Surgical Association

Outcomes and Clinical Trials Committee. Antibiotics

and appendicitis in the pediatric population: an

American Pediatric Surgical Association Outcomes

and Clinical Trials Committee systematic review.

J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(11):2181-2185.

11. Nadler EP, Gaines BA; Therapeutic Agents

Committee of the Surgical Infection Society. The

Surgical Infection Society guidelines on

antimicrobial therapy for children with appendicitis.

Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2008;9(1):75-83.

12. Muehlstedt SG, Pham TQ, Schmeling DJ. The

management of pediatric appendicitis: a survey of

North American pediatric surgeons. J Pediatr Surg.

2004;39(6):875-879.

13. Russell WS, Schuh AM, Hill JG, et al. Clinical

practice guidelines for pediatric appendicitis

20. Saito JM, Chen LE, Hall BL, et al. Risk-adjusted

hospital outcomes for children’s surgery. Pediatrics.

2013;132(3):e677-e688.

21. Le J, Kurian J, Cohen HW, Weinberg G,

Scheinfeld MH. Do clinical outcomes suffer during

transition to an ultrasound-first paradigm for the

evaluation of acute appendicitis in children? AJR Am

J Roentgenol. 2013;201(6):1348-1352.

22. Toorenvliet BR, Wiersma F, Bakker RFR, Merkus

JWS, Breslau PJ, Hamming JF. Routine ultrasound

and limited computed tomography for the

diagnosis of acute appendicitis. World J Surg. 2010;

34(10):2278-2285.

23. Barrier A, Williams DJ, Connelly M, Creech CB.

Frequency of peripherally inserted central catheter

complications in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J.

2012;31(5):519-521.

(Reprinted) JAMA Surgery Published online March 30, 2016

Copyright 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/ by a Vanderbilt University User on 04/01/2016

E7