Unit 8

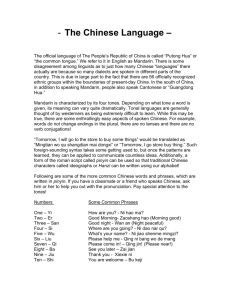

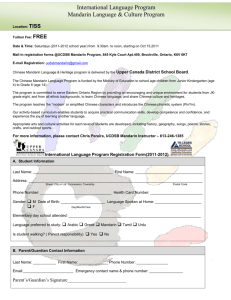

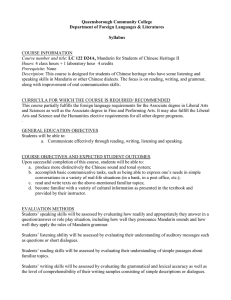

advertisement