“We Had to Pay to Live!” Competing Sovereignties in Violent Mexico 䡲

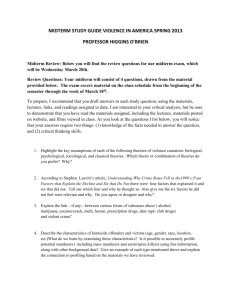

advertisement