URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE IN CHINA Weiping Wu

advertisement

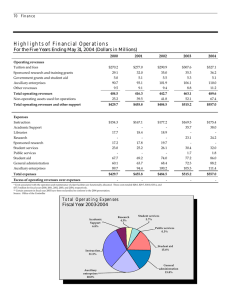

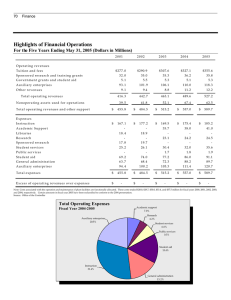

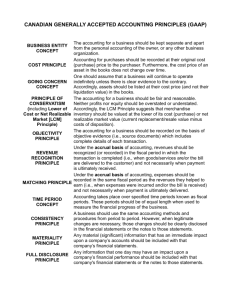

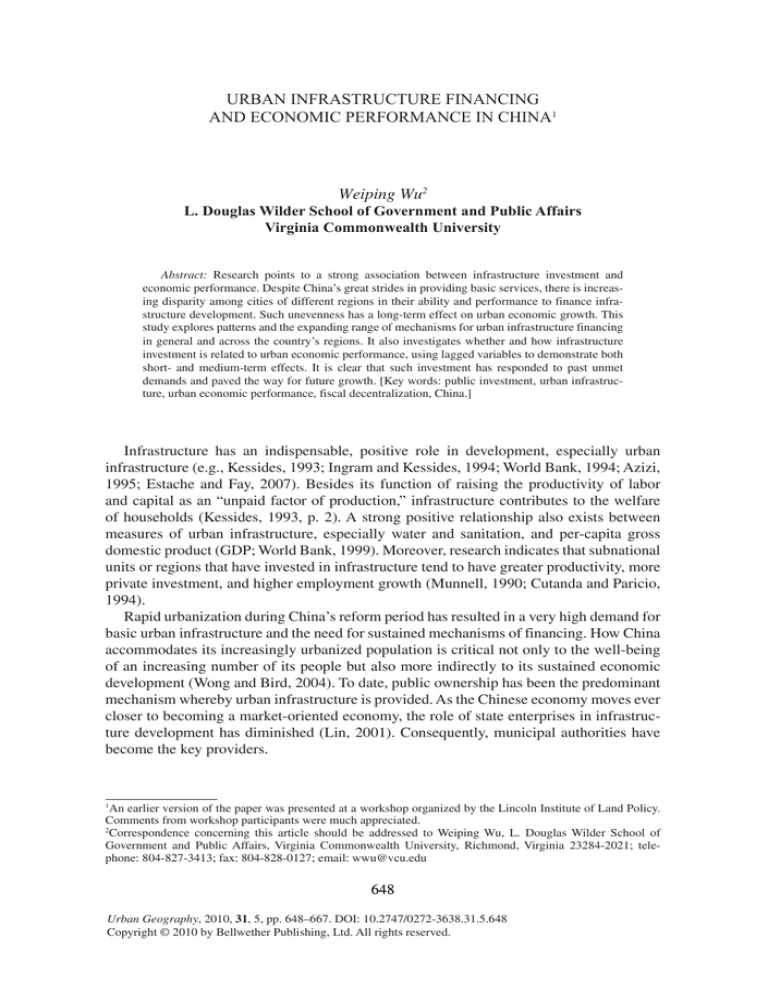

URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE IN CHINA1 Weiping Wu2 L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs Virginia Commonwealth University Abstract: Research points to a strong association between infrastructure investment and e­ conomic performance. Despite China’s great strides in providing basic services, there is increasing disparity among cities of different regions in their ability and performance to finance infrastructure development. Such unevenness has a long-term effect on urban economic growth. This study explores patterns and the expanding range of mechanisms for urban infrastructure financing in general and across the country’s regions. It also investigates whether and how infrastructure investment is related to urban economic performance, using lagged variables to demonstrate both short- and medium-term effects. It is clear that such investment has responded to past unmet demands and paved the way for future growth. [Key words: public investment, urban infrastructure, urban economic performance, fiscal decentralization, China.] Infrastructure has an indispensable, positive role in development, especially urban infrastructure (e.g., Kessides, 1993; Ingram and Kessides, 1994; World Bank, 1994; Azizi, 1995; Estache and Fay, 2007). Besides its function of raising the productivity of labor and capital as an “unpaid factor of production,” infrastructure contributes to the welfare of households (Kessides, 1993, p. 2). A strong positive relationship also exists between measures of urban infrastructure, especially water and sanitation, and per-capita gross domestic product (GDP; World Bank, 1999). Moreover, research indicates that subnational units or regions that have invested in infrastructure tend to have greater productivity, more private investment, and higher employment growth (Munnell, 1990; Cutanda and Paricio, 1994). Rapid urbanization during China’s reform period has resulted in a very high demand for basic urban infrastructure and the need for sustained mechanisms of financing. How China accommodates its increasingly urbanized population is critical not only to the well-being of an increasing number of its people but also more indirectly to its sustained economic development (Wong and Bird, 2004). To date, public ownership has been the predominant mechanism whereby urban infrastructure is provided. As the Chinese economy moves ever closer to becoming a market-oriented economy, the role of state enterprises in infrastructure development has diminished (Lin, 2001). Consequently, municipal authorities have become the key providers. An earlier version of the paper was presented at a workshop organized by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Comments from workshop participants were much appreciated. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Weiping Wu, L. Douglas Wilder School of ­Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia 23284-2021; telephone: 804-827-3413; fax: 804-828-0127; email: wwu@vcu.edu 1 2 648 Urban Geography, 2010, 31, 5, pp. 648–667. DOI: 10.2747/0272-3638.31.5.648 Copyright © 2010 by Bellwether Publishing, Ltd. All rights reserved. URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 649 Infrastructure financing in urban China is fundamentally different from that of most other countries. In industrialized countries, borrowing is widely used as a key method because of the capital-intensive nature of much urban infrastructure, especially in terms of up-front costs (Chan, 1998; Bird, 2004). Most such borrowing emanates directly from a functioning capital market and relies on a system of municipal bond rating. Large cities in particular tend to have better access to bond markets than smaller cities. Excluding borrowing, local taxes are the most important source of infrastructure financing, averaging a 40% share (Chan, 1998). What follows are grants and subsidies as well as other sources that include user charges. Although the situation in developing countries various substantially, local property taxes dominate the revenue structure and loan financing tends to be a minor source. Municipal governments in China, on the other hand, have neither sufficient tax resources to finance infrastructure nor the authority to borrow externally (Wong and Bird, 2004). Under reform, the decentralized fiscal system has mostly worked to the advantage of municipal governments, providing them with better incentives to mobilize local resources. At the municipal level, new mechanisms of financing that have arisen from such fiscal freedom have contributed to the significant expansion of infrastructure investment. However, the central government assigns heavy responsibilities for the provision of nearly all public services to local governments while not adequately supporting them through either revenue assignments or an intergovernmental transfer system. In addition, continuing fiscal decentralization has affected regional patterns of infrastructure financing. As economic growth becomes more concentrated in China’s coastal region, there has been a sharp rise in interregional disparities in fiscal spending accompanied by gradual deterioration in the provision of public services for inland regions. This unevenness in infrastructure development will have long-term effect on national economic development. The main purpose of this study is to explore patterns of financing infrastructure development across cities of different regions, and how infrastructure investment may be related to increasing disparities in urban economic performance. First is a review of the theoretical literature and evidence to show how public investment in infrastructure affects economic performance, particularly in the context of regional development. Next follows an overview of how fiscal decentralization in China during the reform era has altered local finance, which includes an analysis of the expanding range of mechanisms in financing urban infrastructure. The third section examines the increasing disparity among cities of different regions in their ability to finance infrastructure development. Using statistical data on large, prefecture-level cities in China, the final section presents and interprets a regression analysis on the effects of urban infrastructure investment on economic ­performance. This study uses a limited definition of urban infrastructure, often called urban maintenance and construction in China. It includes public utilities (water supply and drainage, residential gas and heating supply, and public transportation), municipal works (roads, bridges, tunnels, and sewerage), parks, sanitation and waste management, and flood control. Note that housing, power, telecommunications, and other transportation sectors (ports, airports, and railway) are not counted under the rubric of urban maintenance and construction (Wu, 1999). 650 WEIPING WU INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE: THE RESEARCH CONTEXT The literature on the contribution of public infrastructure capital to economic growth is substantial, with some of it in the context of regional economics and economic development. Overall, the 1994 World Development Report correlates a 1% increase in GDP with a 1% increase in infrastructure stock across all countries (World Bank, 1994). Exploring the impact of the stock of public capital on economic activity at the state level in the United States, Munnell (1990) concludes that those states that have invested in infrastructure tend to exhibit greater output, more private investment, and higher employment growth. Other research has shown the same findings at the metropolitan-area level in the United States (Munnell, 1990). Similarly, in a study of Spanish regions, large differences in public­capital facilities appear to be significant in accounting for regional income disparities (Cutanda and Paricio, 1994). The core rationale for infrastructural investment that emerges from the theoretical literature is that it raises the marginal product of other capital used in production (Fedderkea et al., 2006). Research points to a strong association between infrastructure investment and output (Munnell, 1990; Easterly and Rebelo, 1993). Improvements in infrastructure services also can have the beneficial effect of increasing households’ real income and quality of life. According to Munnell (1990), the aggregate stock of public capital is found to be positively related to output, and so are highway stock and water and sewer systems. Easterly and Rebelo (1993) find that public investment in transportation and communications is consistently correlated with economic growth. Cutanda and Paricio (1994) confirm in their Spanish study that transport, communications, energy, and water supply networks stand out, exerting a major influence on regional income because of their potential influence on productive activities. The most common methods of examining the impact of public capital on economic activity have been to estimate a production function in which public capital is considered to be an input into the production process (Kelly, 1997). Several studies have done so at the regional level, often using ordinary least squares (OLS) to estimate production functions (e.g., Munnell, 1990; Andrews and Swanson, 1995). Other researchers have examined the relationship between the growth, as opposed to the level, of output and public infrastructure. Results tend to be mixed, not as clear-cut as using output level (Munnell, 1990). Studies also have demonstrated the impact of public capital on factor productivity. For instance, Munnell (1990) shows that public capital investment makes an important contribution to explaining changes in labor productivity in the United States over the 1949–1987 time period. There is evidence that the slowdown of the U.S. productivity is related to the decrease in public infrastructure investment. In addition to public capital in infrastructure, some studies have included other types of public capital such as that in education and social services. The effect of the latter on production appears to be less measurable (Munnell, 1990; Kelly, 1997). In effect, there are opposing views regarding the contribution of social expenditures. Some see social expenditures as unproductive consumption expenditures that inhibit growth, while others contend that social expenditures enhance growth by fostering welfare and productivity improvements (Kelly, 1997). The effects of social expenditures, other than education, on economic growth are often ignored. Regarding education, there is evidence that investment URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 651 in higher education infrastructure predicts subsequent city and regional growth better than investment in physical infrastructure (Florida, 2002). Another aspect of the role of public capital is its impact on private investment. On the one hand, public capital can enhance the productivity of private capital, thereby influencing private investment. In a study of 40 U.S. metropolitan areas, a statistically significant relationship exists between public outlays and private investment (Munnell, 1990). On the other hand, there are concerns about rent seeking and crowding out. There is evidence that initial increments in public capital accelerate growth. Nevertheless, at some point additional increments to public capital reduce growth by creating distortions in the private sector (Kelly, 1997). Public capital also may serve as a substitute for private capital. An analysis of the impact of the stock of public capital on private investment at the state level in the United States shows a weak degree of substitution between the two. Yet it is also clear that a state’s investment in public capital has a significant positive impact on that state’s private employment growth (Munnell, 1990). There is now a growing body of research on how infrastructure affects China’s economic growth at the local and regional levels. Démurger’s (2001) econometric results show that differences in transportation infrastructure contribute significantly to the observed variation in growth performance among provinces between 1985 and 1998. Policies supporting infrastructure improvements could have substantial impacts in reducing disparities in the level of per-capita income among provinces. Focusing on the urban sector, Lin and Song (2002) find that an increase in paved roads is positively and significantly related to growth in per-capita GDP between 1991 and 1998 among China’s cities. Fan and Chan-Kang (2005), on the other hand, show that road development, together with agricultural research and development, irrigation, education, electricity, and telecommunications, have made significant contributions to economic growth and poverty reduction in the rural sector. URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING UNDER CHINA’S DECENTRALIZATION Public finance matters in the provision of urban infrastructure. China’s record of investment in such infrastructure as highways, ports, power plants, and a variety of urban services has been nothing short of astonishing (Wong and Bird, 2004). But its fiscal system remains in transition, the product of decentralization. Much like the macroeconomic reforms, fiscal decentralization has been gradual and incremental, responding to immediate problems with short-term fixes. Prior to the economic reform, the fiscal system was characterized by centralized revenue collection and fiscal transfers. All taxes and profits were collected by local governments, remitted to the central government, and then transferred back to the provinces and municipalities according to their expenditure needs approved by Beijing. Under this fiscal system, municipal revenues were shared with the central or the provincial government for redistribution. For many years, revenue retention rates for municipal authorities were very low and insufficient to allow significant expansion of infrastructure and adequate maintenance. Given the three general levels of governments (central, provincial, and municipal), the lower levels were entirely subordinate to governments of higher rank in fiscal matters (Wong, 1997). The central government controlled urban maintenance and construction revenues, mainly through central budgetary allocation, supplementary project funding, and the ­Public 652 WEIPING WU Utility Surcharge levied on enterprises and commercial users. There were no earmarked taxes or funds for urban construction, and user charges were minimal. As a result, there was no guaranteed steady flow of funds to urban construction from year to year. Indeed, central funding for the urban sector dried up from 1950s to 1970s as Beijing focused on building interior defense facilities. As a result of rigid central-local fiscal relations, municipalities also did not have local finance systems necessary to support infrastructure projects (Dowall, 1993; Chan, 1998). At the local level, the infrastructure sector was a low priority when funds were allocated through municipal budgets. Because of the bias toward industrial production, capital outlays for urban construction were determined by a population account using household registration and tended to be quite limited, often not exceeding one-tenth of total municipal expenditure (Wu, 1999). Central-local fiscal relations have been altered significantly through decentralization efforts since 1980. The central government introduced a new decentralizing fiscal regime that visualized each provincial entity as a “separate kitchen” for fiscal purposes. This, together with subsequent fiscal reform by provinces, allowed many municipalities to retain higher rates of revenue and to allocate funding more freely. After a decade or so of experimenting with various formulas for revenue-sharing, a new set of reform measures were introduced in 1994 to further streamline central-local fiscal relations. Taxes were reassigned between the central and local governments, with a shift from a negotiated system of general revenue sharing to a mix of tax assignments and tax sharing (Wong and Bird, 2004). For the first time, local governments were assigned some taxes with significant revenue-generation capacity as local taxes. As for urban construction, an urban land use tax, a real estate tax, and an urban maintenance and construction tax are now included among local taxes. However, the reform recentralized revenues but left expenditure assignments unchanged. This in turn created a huge fiscal gap for local governments and left them dependent on central transfers to finance expenditures. Under fiscal decentralization, mechanisms for urban infrastructure financing are broadening, particularly through nonstate channels. There are four general sources of funds available for urban infrastructure development (Table 1). The first is budgetary allocation from central and local governments, consistently making up about 15%. The second involves local fiscal revenues: the Urban Maintenance and Construction Tax (collected by local governments as a surcharge on the combined value of Value-Added Tax, product tax, and business tax—7% in cities, 5% in towns and 1% elsewhere), and the Public ­Utility Surcharge (collected by local governments at a rate of 5% to 8% from the turnover of water, electricity, natural gas supplies, public transportation, and local telephone service; Chan, 1998; World Bank, 2000). Set by the central government, these rates are low relative to the financing needs of many cities. Revenues also fluctuate with output levels of enterprises and do not apply to public institutions (or shiye danwei). As a result, local fiscal revenues have counted for a declining share of infrastructure financing. The third and increasingly important mechanism of financing is the collection of fees and user chargers, including an infrastructure connection fee (similar to the U.S. concept of impact fee), although most such nonfiscal revenues were recorded in the “other sources” category in the 1990s. Such income now counts for between 15% and 25% of urban maintenance and construction revenues (Table 1). But the increasing fee/charge income may be misleading as revenue from leasing land-use rights has become an important component, which is not a common source of funding in other developing countries. A more serious URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 653 Table 1. Urban Maintenance and Construction Revenues, 1990–2006 (Billion RMB) Budgetary allocation Central budgetary allocation Local budgetary allocation Local taxes Maintenance and construction tax Public utility surcharge Fees and user charges Water resource fee Infrastructure connection fee User chargesa Land transfer fee Borrowing Domestic loans Foreign capitalb Bonds Stock financing Self-raised funds Other sourcesc Total 1990 1993 1996 2002 2005 2006 2005 (%) 1.09 1.98 2.70 5.95 1.04 8.63 7.60 6.22 5.67 1.15 39.27 79.59 84.25 14.68 6.51 2.26 9.8 3.3 15.78 5.56 31.60 55.13 56.68 10.17 4.99 5.55 7.62 1.02 0.28 0.48 0.61 1.24 2.50 2.45 0.46 8.66 14.29 21.00 2.64 8.94 14.55 19.71 2.68 28.30 59.45 88.19 10.96 0.88 0.25 4.46 1.38 9.57 5.59 2.58 5.21 21.04 4.59 25.47 58.13 11.95 26.05 84.78 87.39 6.11 0.29 0.68 60.08 30.47 315.62 166.99 30.80 9.27 1.71 3.43 0.63 0.10 0.02 94.60 23.23 17.45 30.59 45.26 5.64 542.25 354.06 100.00 a User charges include primarily toll on roads and bridges, wastewater treatment fee, and garbage treatment fee. b Foreign capital includes both direct investment and loans. c A major component of other sources prior to 2002 is infrastructure connection fees. Sources: Wu (1999) and Ministry of Construction (2002–2006). problem lies in the wide range of the fee scale and fee items among cities. Some municipal authorities have included a multitude of infrastructure services in the fee collection and often have requested exorbitant payments (Wu, 1999). This is shown in the case of some 28 different fees imposed on various aspects of real estate development in Shanghai (Bird, 2004). The importance of the fourth source, borrowing from both domestic and foreign sources including foreign investment, is rising—from only about 5% in 1990 to more than 30% in 2005 (Table 1). Domestic borrowing includes not only cash and deposits but also treasury and other financial bonds plus equities. Bank credit also is emerging as an important source of borrowing. China increasingly resembles market economies in which surpluses generated in the household sector are loaned to the enterprise sector to finance a portion of public investment. But banks sometimes are reluctant because infrastructure investment is large, with long terms and lower return rates (Zhang and Wu, 2005). ­Borrowing on the international market is in principle not permitted at the local level, with exceptions approved only by the central government. Fiscal reforms also have selectively allowed certain provincial-level entities the right to issue construction bonds domestically. Aimed 654 WEIPING WU at capturing the high level of household savings, this practice has been growing, but remains a negligible source of infrastructure financing (Wu, 1999). In addition, foreign capital (including government and commercial loans, direct investment, and international bonds) has begun to play a role in financing urban infrastructure. When China started to open infrastructure to overseas investment in the late 1980s, foreign companies responded enthusiastically. China has since attracted money for truly commercial projects, such as joint ventures to build and operate roads and bridges whose costs are expected to be recovered through toll collection. Public–private partnerships (or joint ventures) tend to be a common form of foreign participation in which both sides contribute funds or services (frequently by providing property or land on the Chinese side), and the public sector often is represented by a company directly or indirectly owned by the government (Bellier and Zhou, 2003; Bird, 2004). The emergence of these new mechanisms (primarily the third and fourth sources) has resulted in the increasing importance of extra-budgetary funds, which are still in the public sector but are not subject to central or provincial budgetary control. This indicates a higher degree of municipal fiscal independence. The formal budget is only a part of the fiscal story and not necessarily the most important part. A broad definition of extra-budgetary funds is that they constitute all resources managed directly or indirectly by administrative branches of the government outside the normal budgetary process. Extra-budgetary funds generally include fees and/or funds that are not taxes, such as water resource fees, infrastructure connection fees, and user charges (Table 1). Whereas budgeted funds are under strict supervision, extra-budgetary funds are easier to be manipulated and soften the budgetary constraint for municipal governments. The primary motivation for the development of extra-budgetary funds at the local level is revenue enhancement rather than earmarking (Wong and Bird, 2004). The final source, self-raised funds, makes up 10% to 20% of infrastructure revenues (Table 1) and is an even grayer area in local financing. Though not collected as taxes or budgetary items, extra-budgetary funds nonetheless are specifically authorized by some government body. Sometimes called extra-extrabudgetary funds, off-budgetary funds, or extra-system revenues, self-raised funds are not specifically authorized as a fee or fund (Wong and Bird, 2004). Such revenue is irregular and often nonrecurring, raised by central ministries, local governments, enterprises, or public institutions. It is an indication that fiscal burdens may be passed on to the enterprise sector that is forced to finance public services. For instance, in Dongguan, Guangdong Province, local authorities have experimented with a new method to raise funds. This involves the creation of an energy and communications company that may raise money from state, collective, and private sources for the construction of roads and power plants. The company pays interest on these funds and will repay the capital by collecting user fees and tolls (Harral, 1992). A further indication of privately funded infrastructure services is the rise of premium water networks in some cities. Beginning in the mid-1990s, select residential communities began to bypass municipal water supply systems through the construction of small-scale secondary pipe networks for purified drinking water (Boland, 2007). The difficulty in sorting out local public finance in China is further demonstrated by the practice of land leasing and transfer. Unlike most other transitional economies, China so far has not initiated a privatization program for urban land. It has chosen to preserve state ownership but, since the late 1980s, has permitted market transactions of user rights (as URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 655 distinct from ownership rights) during urban land management reforms. Since land is the most valuable commodity under the control of municipal governments, generating ­revenues from leasing land-use rights and charging land-use fees has become a popular practice. For many localities, land transfer fees are considered to be self-raised funds because they are not specifically authorized as a fee and the revenue varies from year to year. But for others, revenues from land transfer are treated as extra-budgetary. In its current practice, land leasing and transfer is driven by short-term interests of local governments. Many local governments have been dependent on the sale of such leases for a considerable fraction of their revenues and have at the same time been increasingly involved in land and real estate development. Local government’s role is critical to the acquisition of land for development, especially when the conversion of farmland is involved (Wong and Bird, 2004). The use of state assets by the government and its agencies to raise off-budget revenues, however, is a major source of inefficiencies, distorted incentives, and loss of state assets (Wong and Bird, 2004). In addition, sold land-use rights represent foregone sources of income. It is unlikely that cities can count on revenue from asset sales as a major, lasting source of funding to expand infrastructure construction and maintenance. Overall, China’s experience in infrastructure financing is a significant departure from the international norm: the capacity of municipalities to borrow externally is lacking, local property and land taxes are nearly absent, and extra-budgetary funds allow for softer budgetary constraint. The local problems, to a large extent, stem from the changing centrallocal fiscal relations. Although decentralization has allowed more incentives for local governments to mobilize resources, the 1994 tax reform has resulted in significant distortions. There continues to be a mismatch of expenditures and revenues between levels of government. Before 1985, for example, local government revenues were larger than local government expenditures, and local government remitted revenues to the central government. In 1998, 35% of local government expenditures were financed by subsidies from the central government (Lin, 2001). As such, the operation of local governments in public financing often are chaotic, as they cope with funding shortfalls through a variety of offbudge mechanisms. REGIONAL PATTERNS OF INFRASTRUCTURE PROVISION AND FINANCING Regional disparity in economic performance and income has been longstanding in China. Before 1949, more than 70% of China’s industries were concentrated within a ­narrow belt along the country’s east coast. This was largely due to the development of a pre-capitalist (Nationalist) mode of production in the early 20th century—mainly port cities to provide linkages to advanced capitalist countries in their imperialist expansion. Since the establishment of a socialist state, China’s development policies have exacerbated this unequal development pattern. Under the command economy, the pursuit of regional self-sufficiency severely distorted the allocation of resources and aggravated regional unevenness (Fan and Chan-Kang, 2005). After 1979, the tune of socialist planning in China changed to a one of economic efficiency and spatial deployment. Policies introduced since then favor a reorientation to coastal development, reinforcing China’s new effort toward further technological and economic expansion. Consequently, when measured at the provincial level, the most pronounced disparities have arisen mainly between coastal and interior regions (Démurger, 2001). Researchers also have identified capital input ­(including domestic and 656 WEIPING WU Table 2. Level of Urban Infrastructure Services by Region, 1996–2006 Water coverage rate (percent) Eastern region Central region Western region National average Gas coverage rate (percent) Eastern region Central region Western region National average Public transportation vehicle (per 10,000 persons) Eastern region Central region Western region National average Per-capita road area (m2) Eastern region Central region Western region National average Wastewater treatment rate (percent) Eastern region Central region Western region National average 1996 2000 2003 2005 2006 97.67 91.39 96.07 94.89 98.88 93.53 96.63 96.70 90.02 81.66 83.71 86.15 94.45 85.78 89.24 91.09 89.43 86.68 80.97 86.67 83.88 59.97 60.07 73.21 93.81 75.08 73.27 84.15 87.60 64.93 66.42 76.74 90.35 71.62 72.45 82.08 85.80 74.17 67.34 79.11 8.88 5.73 7.92 7.29 11.16 7.93 9.60 9.81 8.57 6.52 7.05 7.66 9.34 7.30 8.58 8.62 10.40 7.84 10.31 9.05 8.90 6.55 7.44 7.56 10.43 7.98 7.22 9.09 10.53 8.10 7.91 9.34 12.28 9.38 8.97 10.92 12.01 10.04 10.42 11.04 27.93 17.76 20.39 23.62 41.40 26.08 24.40 34.25 48.43 37.18 31.48 42.39 58.14 43.43 42.44 51.95 62.47 46.57 44.86 55.67 Sources: Hou (1998), National Bureau of Statistics of China (2006), and Ministry of Construction (2002– 2006). foreign) as the most important determinant of regional inequality in the postreform period (Fan and Sun, 2008). Some attempts to reverse the trend of growing regional inequality began around 1998, when the government started redirecting fiscal resources toward equalization, including the “Go West” development strategy launched in 1999. A major driver of this transfer policy appears to be a concern for growing regional disparities that many consider have detracted from the country’s impressive growth performance (Wong and Bird, 2004; Chan and Wang, 2008; Fan and Sun, 2008). There are noticeable differences in nearly all available aggregate indicators of urban infrastructure services across the three broad regions (eastern, central, and western), even though China has made significant progress at an aggregate level (Table 2). Cities in the eastern region uniformly enjoy higher levels of service in all sectors, with markedly higher percentages of population having access to piped water and wastewater treatment. In many inland provinces, local infrastructures such as public transportation, roads, streets, water supply, and waste treatment are in poorer condition. The major reasons for this and the slower infrastructure growth include low government spending on infrastructures URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 657 stemming from low government revenues (Lin, 2001). Since the early 2000s, rapid urban expansion appears to have caused a slight setback across the regions (Table 2) in levels of service. In response to the growing demand for water, however, the central government made the development of water and wastewater infrastructure a national priority in the 1990s. As a result, urban wastewater treatment capacity has grown substantially in recent years, particularly in the eastern region (Table 2). Continuing fiscal decentralization also has affected regional patterns of infrastructure financing. In particular, there are substantial distortions associated with the new tax sharing system created as part of the 1994 reform. By sharing value-added tax revenues with local governments at a flat rate by origin, the system introduced a highly unequalizing feature to revenue sharing, ensuring that revenue-rich provinces kept more. Specifically, coastal provinces gained higher revenue shares than inland provinces. From 1993 to 1998, for instance, the ratio of provincial per-capita fiscal expenditures in Shanghai (in eastern region) grew from 2.8 to 4.5 times the national average, and in Beijing from 2.0 to 3.0. In contrast, the ratio fell in Gansu (western region) from 0.76 to 0.61, and in Hunan (central region) from 0.60 to 0.52 (Wong and Bird, 2004). More specifically, a supporting system has yet to be put in place to ensure minimum standards of service provision across the regions. As wealth has become more concentrated in the coastal region since the 1990s, there has been a sharp rise in interregional disparities in fiscal spending accompanied by a gradual deterioration in public services provided in the inland provinces (Wong and Bird, 2004). The western region, for example, relies much more on budgetary allocation and borrowing to finance urban infrastructure and has far less ability to raise funds from extrabudgetary sources (Fig. 1). There is a general regional disparity in the level of urban infrastructure financing, although the patterns are not uniform within each region. Overall, provinces in the eastern region have fared better. From 1996 to 2006, for instance, Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang enjoyed per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues that were more than twice the national average. But there is substantial variation within the coastal region. Provinces on the southeast coast (e.g., Guangxi, Fujian, Hainan) saw their revenue levels decline relative to national averages. Some provinces in the western region, particularly Chongqing as the newly designated provincial-level city, experienced more rapid growth in the level of urban infrastructure investment (Table 3). The central region in general, on the other hand, lagged behind. Regional patterns in urban infrastructure financing appear to have shifted in tandem with the progress of economic reforms across China. In 1996, provinces with the highest levels of per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues, as compared to the national average, tended to be on the southeast coast (including Guangdong, Fujian, ­Zhejiang, and Shanghai). This was the place where market reforms took hold earlier. As reforms spread north and west, the growth of the Yangzi Delta area has become more prominent and the Bohai area also is rising. Provinces in these areas (e.g., Zhejiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, ­Beijing) now stand out as major investors in urban infrastructure. Some of the poorest provinces, primarily in the central and western regions (e.g., Anhui, Henan, Hubei, Gansu), continue to lose ground in their capacity to finance urban infrastructure (Fig. 2). 658 WEIPING WU Fig. 1. Urban maintenance and construction revenues by region, 2002 and 2005. Sources: Ministry of ­Construction (2002, 2005). DOES INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT MATTER FOR URBAN ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE? To explore whether infrastructure investment contributes significantly to urban economic performance, a database of prefecture-level Chinese cities was constructed (it includes all large cities and provincial capitals except Lhasa). In the strictest sense of the term, a prefecture-level city is not an equivalent of a city or municipality. Rather, it is an administrative unit comprising both an urban core (a city in the strict sense) and surrounding less-urbanized and rural areas. In fact, such delineation applies to cities at all levels in China (Chan, 2007). Prefecture-level cities nearly always contain multiple counties, county-level cities, and other similar units. As a result, they can be considered the Chinese version of the term “metropolitan area” used in many other countries. Official statistics collected on these cities, hence, include data on both the entire jurisdiction of a prefecturelevel city (quan shi) and the urban core (shi qu). This study uses the former as the level of analysis, and shows patterns at the metropolitan level. Using this database, I have conducted an OLS analysis to estimate and compare the effects of infrastructure investment as well as a set of other predictors. Because of limited data availability, estimating a Cobb-Douglas production function at the level of metropolitan area is not feasible. Instead, growth in per-capita GDP (∆GDP) functions as the dependent variable. Research has highlighted the fact that causality may run both ways between growth and infrastructure. Infrastructure contributes to growth and growth causes greater demand for (and usually supply of) infrastructure (Estache and Fay, 2007). Endogeneity also would be present, particularly when both GDP per-capita and infrastructure URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 659 Table 3. Per-Capita Urban Maintenance and Construction Revenues by Province, 1996–2006a Investment (RMB) 1996 2000 Index (national average = 1) 2003 2006 1996 2000 2003 2006 Eastern region Beijing 613 2,848 2,429 1,607 1.37 3.00 1.92 2.94 Tianjin 436 1,046 2,219 465 0.97 1.10 1.75 0.85 Hebei 304 764 1,306 375 0.68 0.80 1.03 0.69 Liaoning 361 636 835 488 0.80 0.67 0.66 0.89 Shanghai 1,325 2,824 2,951 850 2.95 2.98 2.33 1.55 706 1,116 2,307 959 1.57 1.18 1.82 1.75 1,038 3,154 3,645 1,018 2.31 3.32 2.88 1.86 614 889 1,063 535 1.37 0.94 0.84 0.98 Jiangsu Zhejiang Fujian Shandong 350 787 1,013 651 0.78 0.83 0.80 1.19 Guangdong 711 1,346 835 775 1.58 1.42 0.66 1.42 Guangxi 466 597 1,213 532 1.04 0.63 0.96 0.97 Hainan 496 1,058 442 167 1.10 1.11 0.35 0.31 Central region Shanxi 259 328 427 389 0.58 0.35 0.34 0.71 Inner Mongolia 219 617 1,057 616 0.49 0.65 0.84 1.13 Jilin 327 428 615 277 0.73 0.45 0.49 0.51 Heilongjiang 170 531 690 292 0.38 0.56 0.55 0.53 Anhui 362 567 668 275 0.81 0.60 0.53 0.50 Jiangxi 227 360 1,238 371 0.51 0.38 0.98 0.68 Henan 299 433 601 279 0.67 0.46 0.47 0.51 Hubei 163 486 507 162 0.36 0.51 0.40 0.30 Hunan 480 660 1,199 382 1.07 0.69 0.95 0.70 – 668 1,645 994 – 0.70 1.30 1.82 Western region Chongqing Sichuan 385 729 1,796 286 0.86 0.77 1.42 0.52 Guizhou 301 559 558 112 0.67 0.59 0.44 0.20 Yunnan 494 730 931 201 1.10 0.77 0.74 0.37 84 93 110 189 0.19 0.10 0.09 0.35 Tibet Shaanxi 347 542 992 314 0.77 0.57 0.78 0.57 Gansu 202 423 384 219 0.45 0.45 0.30 0.40 Qinghai 242 1,370 761 661 0.54 1.44 0.60 1.21 Ningxia 221 821 891 497 0.49 0.87 0.70 0.91 Xinjiang 310 865 1,446 413 0.69 0.91 1.14 0.75 National average 449 949 1,265 547 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 a Only the 2006 provincial aggregate data include migrants in the calculation of per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues, which explains the drop in the overall levels. A dash (–) means that data are not available. Sources: Hou (1998) and Ministry of Construction (2002–2006). 660 WEIPING WU Fig. 2. Index of per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues by province, 1996 and 2006 (national average = 1). Sources: Hou (1998) and Ministry of Construction (2006). URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 661 i­nvestment variables are flows. Even though disentangling the two is complex, it is possible to devise estimation methods that make it clear which way causality runs. In addition, there are lags in infrastructure’s impact on growth. Much infrastructure is long lived, and its full impact is slow in coming. While it may be reasonable to say that roads constructed five years ago are still causing growth, it would be difficult to argue the reverse (Seethepalli et al., 2008). As such, this analysis uses lagged variables for both per-capita infrastructure investment (in the form of urban maintenance and construction revenues) and per-capita education investment as predictors to clarify the direction of causality. In addition, unemployment rate is used to control for both cyclical and long-term trends in productivity (Andrews and Swanson, 1995). Per-capita foreign direct investment is used to approximate the level of private investment, since there is no adequate information on other types of private investment. Other important predictors of growth include industrial composition (approximated by the percentage of manufacturing in the total employment mix) and firm ownership structure (percentage of the private sector or geti in total employment). These two variables serve to control for differences in industrialization and market reform processes. Regional dummy variables are added to capture the broad regional fixed effect. Data are drawn from the China Statistical Yearbook for Cities and the China Urban Construction Statistical Report. Important data issues arise. First, Chinese data on urban population are known to be problematic (Chan, 2007; Fan and Sun, 2008). Population estimates from census sources differ considerably from pre-census and post-census estimates in the yearbook source. This analysis draws from yearbook sources exclusively and uses total population figures (rather than nonagricultural population). Second, migrants without local household registration are not always counted in the urban population (Chan, 2007; Chan and Wang, 2008). The 2000 Census was a turning point in that population was enumerated for the first time in their place of residence and not place of registration. As such, data on the migrant segment of urban population became more readily available after 2000. For the years 2002–2005, per-capita data for GDP and other variables in the regression analysis are adjusted to include migrants in the total population. Per-capita data for earlier years (1999 and 2000), however, are not adjusted in this way. Third, real per-capita GDP often is derived from the official nominal GDP data in conjunction with official GDP deflators (Fan and Sun, 2008). This study utilizes per-capita GDP data converted into 2000 constant prices. To ascertain the short- and medium-term effects, two models were constructed using two-year and five-year lags. Research from another large developing country, India, shows that sustained increase in public investment in infrastructure can accelerate real macroeconomic growth both in the medium (3–5 years) to long (6–10 years) run (Murty and Soumya, 2006). The first model uses classical pooling of cities for the years 2004 and 2005 lagged against two-year-prior investment levels (2002 and 2003), with migrants included in population counts. A second model uses pooling of cities for years 2004 and 2005 lagged against five-year-prior investment levels (1999 and 2000), without counting migrants (Tables 4 and 5). Descriptive statistics shows that GDP growth varies substantially in both periods, as indicated by the sizeable standard deviation; so do levels of investment in infrastructure and education as well as foreign direct investment (Table 4). It is clear that there are significant disparities across cities in economic performance, public 662 WEIPING WU Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for Prefecture-Level Citiesa Mean 2-year lag model ∆GDP per capita (2-year, RMB) Per-capita investment in education (2-year prior, RMB) Per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues (2-year prior, RMB) Per-capita foreign direct investment (US$) Std. dev. b Share of private sector in employment (percent) Share of manufacturing sector in employment (percent) Unemployment rate (percent) Eastern region Central region 2,539.76 210.88 242.66 3,196.49 125.86 404.69 57.36 104.31 37.58 42.03 4.20 0.40 0.39 12.29 13.41 2.60 4,873.57 144.13 689.87 4,783.11 93.97 706.75 63.37 37.63 43.93 4.26 0.43 0.39 107.54 12.40 13.06 2.71 N = 551 5-year lag modelc ∆GDP per capita (5-year, RMB) Per-capita investment in education (5-year prior, RMB) Per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues (5-year prior, RMB) Per-capita foreign direct investment (US$) Share of private sector in employment (percent) Share of manufacturing sector in employment (percent) Unemployment rate (percent) Eastern region Central region N = 482 All data are from the China Statistical Yearbook for Cities except that those on per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues are from the China Urban Construction Statistical Report. b Includes migrants in the calculation of per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues, and percapita investment in education. c Migrants are not included in the calculation of per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues, and per-capita investment in education. Sources: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2000–2006), Ministry of Construction (1999–2005). a investment, and private investment. The OLS models are run with simultaneous entry, not stepwise procedures, because the latter tends to capitalize on random variations in the data. There is no problem of multicollinearity in the models since no variables display tolerance levels less than 0.2 (Table 5). As regression coefficients are unit dependent, the discussion below focuses on standardized coefficients to assess the extent to which each predictor is influential. The two models have produced consistent results. Both indicate that per-capita infrastructure investment is a statistically significant predictor for per-capita GDP growth (Table 5). It is, in fact, the single most important predictor in the short run, followed by the share of manufacturing employment and level of foreign direct investment. Its effect pales somewhat against the two other factors in the medium term. These results show that better economic growth in Chinese cities is driven by public infrastructure investment, the URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 663 Table 5. Regression Models on Per-Capita GDP Changec 2-year lag model Constant Per-capita investment in education (2-year prior) Per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues (2-year prior) Per-capita foreign direct investment Standardized coefficient t-value Significance Tolerance 0.036 0.268 –1.013 0.726 5.766 0.312 0.468 0.000 0.512 0.586 0.179 3.512 0.000 0.490 –0.026 0.264 –0.028 –0.030 0.016 0.302 –0.701 6.839 –0.778 –0.562 0.327 0.484 0.000 0.437 0.574 0.744 0.905 0.850 0.948 0.453 0.558 0.044 0.190 –1.454 0.977 4.330 0.147 0.329 0.000 0.614 0.649 0.347 –0.020 0.282 0.003 –0.017 0.010 6.947 –0.531 7.301 0.084 –0.318 0.190 0.000 0.595 0.000 0.933 0.751 0.849 0.500 0.903 0.836 0.926 0.423 0.493 a Share of private sector in employment Share of manufacturing sector in employment Unemployment rate Eastern region Central region Adjusted R2 5-year lag modelb Constant Per-capita investment in education (5-year prior) Per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues (5-year prior) Per-capita foreign direct investment Share of private sector in employment Share of manufacturing sector in employment Unemployment rate Eastern region Central region Adjusted R2 0.399 c All data are from the China Statistical Yearbook for Cities except that those on per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues are from the China Urban Construction Statistical Report. a Includes migrants in the calculation of per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues, and percapita investment in education. b Migrants are not included in the calculation of per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues, and per-capita investment in education. Sources: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2000–2006), Ministry of Construction (1999–2005). expansion of the manufacturing sector, and foreign capital. The contribution of foreign capital is likely more substantial for cities in the eastern region, as major port cities and their surroundings have become preferred places for global investors (Zheng et al., 2009). Per-capita investment in education is not a significant contributor in both models, confirming results from studies on U.S. states (Munnell, 1990) and 73 countries worldwide (Kelly, 1997); public capital in infrastructure has a far more significant effect on economic performance than social expenditures. However, per-capita investment in education may not be the best indicator of the quality of educational services, since such investment tends to be channeled to physical facilities. The broad classification of regions also does not significantly predict per-capita GDP growth. This indicates there is a sizeable variation in economic performance among cities within the same region. 664 WEIPING WU The effects of infrastructure investment on urban economic performance likely take place in several ways. Its contribution is well documented in terms of raising the productivity of labor and capital, as well as increasing the welfare of households. Given the rapid pace of urbanization in China, its role in meeting both past-due and anticipated demands is noteworthy. First, infrastructure investment can respond to unmet demands and needs, which often represent obstacles to current economic performance and future growth. Access to infrastructure services also helps individuals get connected to core economic activities, allowing them to access additional productive opportunities (Seethepalli et al., 2008). Through sensible investment and travel demand management, for instance, congestion and associated costs can be reduced. The city of Shanghai provides such an example. With only about 10% of the urban area devoted to roads, its central area inherited an antiquated transportation network from the early twentieth century designed for pedestrians and bicycles. After major investment in public transportation and support infrastructure (e.g., bridge and tunnel crossings) with the assistance of international lending agencies, the downtown area of the city has avoided the kind of traffic congestion now frequently seen in other large Chinese cities (Wu, 2007). A report from the Guangzhou Academy of Social Sciences indicates traffic jams cost Guangzhou up to 12 billion RMB a year, about 7% of its GDP (“Beijing Wrestles with Urban Traffic Congestion,” 2006). Second, investment in public infrastructure can be used to anticipate future development and to stimulate investment in other sectors and economic growth in future years (ADB, 2002). The medium-term effect is confirmed by the results from this analysis and elsewhere. Where infrastructure facilities are developed, it is easier for entrepreneurs to adopt new technologies and consequently generate technical progress and economic growth (Démurger, 2001). Today’s increasingly knowledge-based economy in particular calls for such facilities as cable networks for advanced telecommunications, wired and energy-saving structures, and backup power and telecommunications lines (Bird, 2004). Most Chinese cities, with the exception of a few large ones, have yet to offer such services, but Shanghai’s recent undertaking may be a promising lead. A five-year key project has been launched to integrate all the circuits and pipelines for telecom services into an underground broadband pipeline. Upon completion, this project not only offers a strong backbone for the city’s development as an Internet-smart metropolis, but it also reduces environmental pollution as well as accidents caused by open-air circuit poles and lines (Yusuf and Wu, 2002). CONCLUSION Research at the national and regional levels has pointed to a positive contribution of public infrastructure investment to economic performance in both industrialized and developing countries. Differences in public capital facilities also appear to play a significant role in accounting for regional income disparities. While still facing the daunting task of equipping its cities with modern infrastructure, China has made great strides forward in providing basic services and perhaps performed better than most of its counterparts with similar national income levels. However, there is an increasing disparity among cities of different regions in their ability and performance to finance urban infrastructure. Stemming from a historical legacy and more recent waves of fiscal decentralization, this unevenness likely has a longer term effect on urban economic growth. URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 665 Although fiscal decentralization generally offers local governments more incentives to mobilize resources, the 1994 tax reform has strengthened the authority of the central government over budgetary control. The unified revenue-sharing ratio has ensured that the more prosperous provinces with stronger revenue-generating capabilities receive more tax revenues per capita. This undermines the ability of lagging provinces in central and western China to undertake needed infrastructure investments even with substantial redistribution of tax revenues from the central authority. Such distortions have spatial implications, producing greater regional disparities. It is clear that levels of infrastructure service differ substantially across cities in the three regions, and so do their methods and abilities to finance public facilities. Bestowed with most of the responsibilities for service provision, local governments cope with funding shortfalls through a variety of off-budget mechanisms. Cities in the western region have the fewest opportunities to raise funds from extra-budgetary sources. Instead, they rely much more on budgetary allocation and borrowing to finance new urban infrastructure. Overall, provinces in the eastern region have experienced higher levels of financing. Zhejiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Beijing especially stand out as major investors in urban infrastructure. The central region in general has lagged behind in this respect, and some of the poorest provinces continue to lose ground. An analysis using data on prefecture-level cities (the equivalent of metropolitan areas) shows that infrastructure investment is a statistically significant predictor for urban economic performance. Per-capita GDP growth is regressed as a function of two lagged variables—per-capita urban maintenance and construction revenues and per-capita investment in education—to ascertain both their short- and medium-term effects. Two other predictor variables, per-capita foreign direct investment and manufacturing’s share in total employment, have significant effects as well. This analysis also points to the sizeable variation in economic performance among cities within the same region. It is clear that infrastructure investment is justified in both responding to unmet demands from the past and paving the way for future economic growth. REFERENCES Andrews, K. and Swanson, J., 1995, Does public infrastructure affect regional performance? Growth and Change, Vol. 26, 204–216. Asian Development Bank (ADB), 2002, Strengthening Public Infrastructure Investment Policy in China: Strategic Options for Central, Provincial and Local Governments. Retrieved May 24, 2009 from http://www.adb.org/Documents/Reports/PRC-PublicInfrastructure/TA3253-Final.pdf Azizi, M. M., 1995, The provision of urban infrastructure in Iran: An empirical evaluation. Urban Studies, Vol. 32, 507–522. “Beijing Wrestles with Urban Traffic Congestion,” November 17, 2006, Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved March 18, 2009, from http://chinagate.cn/english/develop/49305.htm Bellier, M. and Zhou, Y. M., 2003, Private Participation in Infrastructure in China: Issues and Recommendations for the Road, Water, and Power Sectors. Washington, DC: The World Bank, Working Paper No. 2. Bird, R. M., 2004, Getting It Right: Financing Urban Development in China. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto, Institute for International Business, International Tax 666 WEIPING WU Program Paper 0413, November. Retrieved May 24, 2009 from http://www.rotman. utoronto.ca/iib/ITP0413.pdf Boland, A., 2007, The trickle-down effect: Ideology and the development of premium water networks in China’s cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 31, 21–40. Chan, K. W., 1998, Infrastructure services and financing in Chinese cities. Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal, Vol. 7, 503–528. Chan, K. W., 2007, Misconceptions and complexities in the study of China’s cities: Definitions, statistics, and implications. Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 48, 383–412. Chan, K. W. and Wang, M., 2008, Remapping China’s regional inequalities, 1990–2006: A new assessment of de facto and de jure population data. Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 49, 21–56. Cutanda, A. and Paricio, J., 1994, Infrastructure and regional economic growth: The Spanish case. Regional Studies, Vol. 28, 69–78. Démurger, S., 2001, Infrastructure development and economic growth: An explanation for regional disparities in China? Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 29, 95–117. Dowall, D. E., 1993, Establishing urban land markets in the People’s Republic of China. Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 59, 182–192. Easterly, W. and Rebelo, S., 1993, Fiscal policy and economic growth: An empirical investigation. Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 32, 417–458. Estache, A. and Fay, M., 2007, Current Debates on Infrastructure Policy. Unpublished paper prepared for the Growth Commission, Yale University, September 28–29. Fan, C. C. and Sun, M., 2008, Regional inequality in China, 1978–2006. Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 49, 1–20. Fan, S. and Chan-Kang, C., 2005, Road Development, Economic Growth, and Poverty Reduction in China. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute, Research Report 138. Fedderkea, J. W., Perkins, P., and Luiz, J. M., 2006, Infrastructural investment in long-run economic growth: South Afrca 1875–2001. World Development, Vol. 34, 1037–1059. Florida, R., 2002, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, ­Leisure and Community. New York, NY: Basic Books. Harral, C. G., editor, 1992, Transport Development in Southern China. Washington, DC: The World Bank, Discussion Paper No. 151. Hou, J., editor, 1998, China Urban and Rural Construction Development Report, 1997. Beijing, China: China Urban Press (Zhongguo Chengshi Chubanshe). Ingram, G. and Kessides, C., 1994, Infrastructure for development. Finance and Development, Vol. 31, 18–21. Kelly, T., 1997, Public expenditures and growth. Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 34, 60–84. Kessides, C., 1993, The Contributions of Infrastructure to Economic Development: A Review of Experience and Policy Implications. Washington, DC: The World Bank, ­Discussion Paper No. 213. Lin, S., 2001, Public infrastructure development in China. Comparative Economic Studies, Vol. 43, 83–109. URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING IN CHINA 667 Lin, S. and Song, S., 2002, Urban economic growth in China: Theory and evidence. Urban Studies, Vol. 39, 2251–2266. Ministry of Construction, 1999–2006, China Urban Construction Statistical Report. ­Beijing, China: Ministry of Construction. Munnell, A. H., with the assistance of L. M. Cook, 1990, How does public infrastructure affect regional economic performance? New England Economic Review, 11–33. Murty, K. N. and Soumya, A., 2006, Effects of Public Investment in Infrastructure on Growth and Poverty in India. Mumbai, India: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (WP-2006-006). National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2000–2006, China Statistical Yearbook for Cities. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press. Seethepalli, K., Bramati, M. C., and Veredas, D., 2008, How Relevant Is Infrastructure to Growth in East Asia? Washington, DC: The World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 4597. Wong, C. P. W., 1997, Overview of issues in local public finance in the PRC. In C. P. W. Wong, editor, Financing Local Government in the People’s Republic of China. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 27–60. Wong, C. P. W. and Bird, R., 2004, China’s Fiscal System: A Work in Progress. Unpublished paper presented to the Conference on China’s Economic Transition, Pittsburgh, PA, November. World Bank, 1994, World Development Report 1994: Infrastructure for Development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. World Bank, 1999, World Development Report 1999/2000: Entering the 21st Century. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. World Bank, 2000, Proceedings of Workshop on China’s Urbanization Strategy: Opportunities, Issues, and Policy Options. Beijing, China: World Bank Office. Wu, W., 1999, Reforming China’s institutional environment for urban infrastructure provision. Urban Studies, Vol. 36, 2263–2282. Wu, W., 2007, Urban infrastructure and financing in China. In Y. Song and C. Ding, ­editors, Urbanization in China: Critical Issues in an Era of Rapid Growth. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 251–269. Yusuf, S. and Wu, W., 2002, Pathways to a world city: Shanghai rising in an era of globalization. Urban Studies, Vol. 39, 1213–1240. Zhang, Y. and Wu, Q., 2005, Urban Infrastructure Provision and Management. Beijing, China: Economic Science Press. Zheng, Y., Chen, T., Cai, J., and Liu, S., 2009, Regional concentration and region-based urban transition: China’s mega-urban region formation in the 1990s. Urban Geography, Vol. 30, 312–333.