Working paper,1990, presented at Transportation Research Board Annual Conference, 1990

advertisement

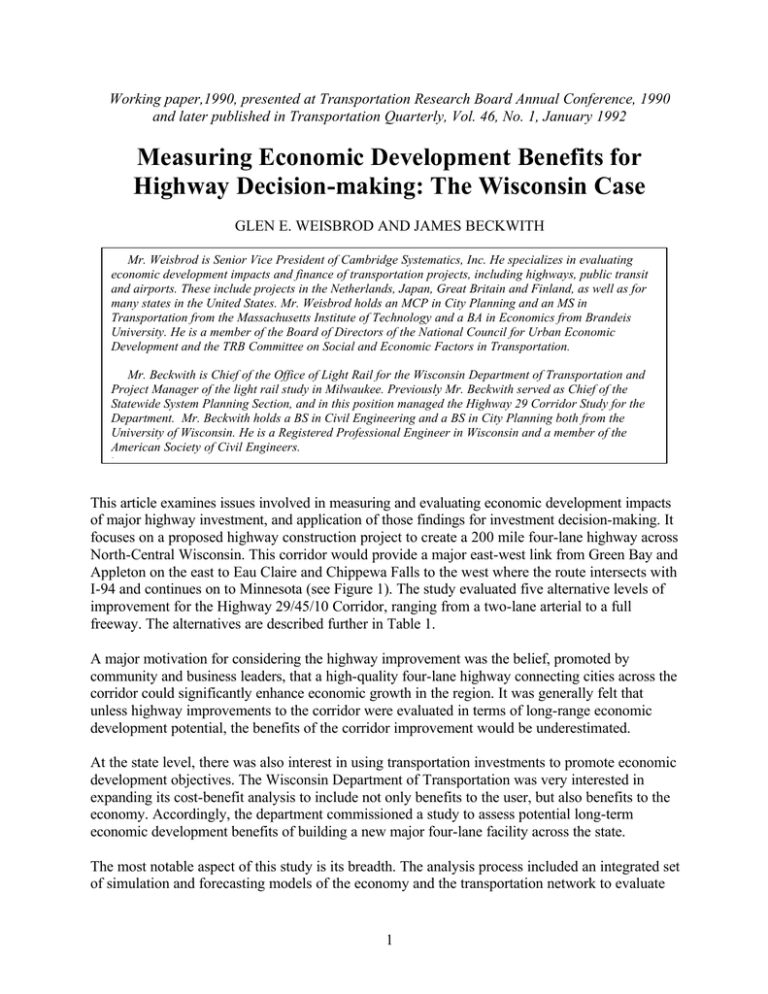

Working paper,1990, presented at Transportation Research Board Annual Conference, 1990 and later published in Transportation Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 1, January 1992 Measuring Economic Development Benefits for Highway Decision-making: The Wisconsin Case GLEN E. WEISBROD AND JAMES BECKWITH Mr. Weisbrod is Senior Vice President of Cambridge Systematics, Inc. He specializes in evaluating economic development impacts and finance of transportation projects, including highways, public transit and airports. These include projects in the Netherlands, Japan, Great Britain and Finland, as well as for many states in the United States. Mr. Weisbrod holds an MCP in City Planning and an MS in Transportation from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a BA in Economics from Brandeis University. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the National Council for Urban Economic Development and the TRB Committee on Social and Economic Factors in Transportation. Mr. Beckwith is Chief of the Office of Light Rail for the Wisconsin Department of Transportation and Project Manager of the light rail study in Milwaukee. Previously Mr. Beckwith served as Chief of the Statewide System Planning Section, and in this position managed the Highway 29 Corridor Study for the Department. Mr. Beckwith holds a BS in Civil Engineering and a BS in City Planning both from the University of Wisconsin. He is a Registered Professional Engineer in Wisconsin and a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. | This article examines issues involved in measuring and evaluating economic development impacts of major highway investment, and application of those findings for investment decision-making. It focuses on a proposed highway construction project to create a 200 mile four-lane highway across North-Central Wisconsin. This corridor would provide a major east-west link from Green Bay and Appleton on the east to Eau Claire and Chippewa Falls to the west where the route intersects with I-94 and continues on to Minnesota (see Figure 1). The study evaluated five alternative levels of improvement for the Highway 29/45/10 Corridor, ranging from a two-lane arterial to a full freeway. The alternatives are described further in Table 1. A major motivation for considering the highway improvement was the belief, promoted by community and business leaders, that a high-quality four-lane highway connecting cities across the corridor could significantly enhance economic growth in the region. It was generally felt that unless highway improvements to the corridor were evaluated in terms of long-range economic development potential, the benefits of the corridor improvement would be underestimated. At the state level, there was also interest in using transportation investments to promote economic development objectives. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation was very interested in expanding its cost-benefit analysis to include not only benefits to the user, but also benefits to the economy. Accordingly, the department commissioned a study to assess potential long-term economic development benefits of building a new major four-lane facility across the state. The most notable aspect of this study is its breadth. The analysis process included an integrated set of simulation and forecasting models of the economy and the transportation network to evaluate 1 FIGURE 1. HIGHWAY 29/45/10 LOCATIONS. See Table 1 for explanation of route alternatives. TABLE 1-DESIGN CHARACTERISTICS OF HIGHWAY ALTERNATIVES Two Route Alternatives most notableReplacement aspect of this study29is(Eau its breadth. analysis process included an integrated set ·The 29/45 Upgrade - WIS Claire toThe Green Bay) and U.S. 45 (E. of Wausau to Appleton) ofconnecting simulationtoand forecasting models of the economy and the transportation network to evaluate Highway 29. potential impacts of this major investment. addition benefitsPoint to auto · 29/10 Upgrade Replacement -highway WIS 29 (Eau Claire toIn Green Bay) to andprojecting U.S. 10 (Stevens to Appleton) travelers, thetostudy focused onU.S. estimating impacts on expansion of existing business, attraction of connecting Highway 29 via 51 freeway. new Design business, andAlternatives tourism growth. Specific attention focused on providing a rigorous framework Five Level for benefit assessment that avoids double counting, a typical problem of economic impact · Freeway- A full 4-lane, limited access divided highway, meeting interstate highway standards and assessment. In addition, was given to of providing a methodology for estimating therefore eligible for a 65attention mph speed limit. Most the freeway would be constructed on new alignment in transportation and economic impacts that adequately recognizes implications of business order to bypass built-up areas around all communities. efficiency benefits, a shortcoming of some prior economic assessment studies. · Freeway/Expressway I-About 35% of the finished highway would be constructed as 4-lane "freeway; ' the rest would be constructed as "expressway." The major difference between expressway and freeway design This article provides an overview how economic impacts wererequiring measured, analysis is that an expressway allows some of at-grade intersections rather than thatdescribes all access the to the highway modeling techniques used and shows how benefit-cost analysis was applied for highway be through interchanges. (Later upgrading of the highway and intersections would be possible.) Under investment decision-making. current law, the speed limit for a freeway/expressway combination would be 55 mph. · FreewaylExpresswayII-The primary design difference between this and the previous alternative is fewer interchanges andREVIEW more at-grade intersections with other public highways. About 15% of the finished LITERATURE highway would be constructed as 4-lane freeway; the rest would be constructed as 4-lane "expressway." (Later evaluating upgrading of the highway and intersection would be possible.) Before economic impacts of proposed highway projects, it is important to understand ·the Base Case -The parallels the department's normal improvement schedule by limitations of base priorcase research studies on this topic. In fact, a major aspect offor thehighways economic proposing 4-laneissections onlyhave warranted on strictly traffic capacity needs. Under this alternative,very about impact literature that there been several discrete directions of research, addressing 35% of the corridor highways would be 4-lane by the year 2000. different sets of issues. Overall, they provide only limited guidance for local economic ·development No Build-This alternative represents the point of reference against which to measure the additional costs evaluations. and benefits of each of the four above alternatives. It represents maintenance of the highway segments at their current 2-lane design. 2 potential impacts of this major highway investment. In addition to projecting benefits to auto travelers, the study focused on estimating impacts on expansion of existing business, attraction of new business, and tourism growth. Specific attention focused on providing a rigorous framework for benefit assessment that avoids double counting, a typical problem of economic impact assessment. In addition, attention was given to providing a methodology for estimating transportation and economic impacts that adequately recognizes implications of business efficiency benefits, a shortcoming of some prior economic assessment studies This article provides an overview of how economic impacts were measured, describes the analysis modeling techniques used and shows how benefit-cost analysis was applied for highway investment decision-making. Literature Review Before evaluating economic impacts of proposed highway projects, it is important to understand the limitations of prior research studies on this topic. In fact, a major aspect of the economic impact literature is that there have been several discrete directions of research, addressing very different sets of issues. Overall, they provide only limited guidance for local economic development evaluations. For instance, one set of research studies has shown the relationship of national highway investments to reducing shipping costs and increasing business productivity.' These studies generally find evidence, through national time series statistics, of increasing business productivity over time associated with reducing shipping costs as a result of upgrading the national highway network. Such findings, however, are not transferable for evaluation of specific individual highway improvements, where geographic differences in travel patterns and economic patterns become important considerations. Another set of economic modeling studies analyzed the relationship of highway locations to nearby business growth patterns.2 There have also been case studies that have attempted to document shifts in business growth patterns associated with specific new freeways.3 Most of these 1. Theodore Keeler, "Public Policy and Productivity in the Trucking Industry," American Economic Review 76 (1986): 153-158; Ann F. Friedlaender, The Interstate Highway System, (North Holland Press, 1965); and A.F. Daugherty et al., "An Economic Analysis of the Cost and Production Structure of the Trucking Industry," in A.F. Daugherty, ed., Analytic Studies in Transport Economics (Cambridge University Press, 1965). 2. Curtis Harris, Regional Economic Effects of Alternative Highway Systems (Ballinger Brooks, 1974); Jack Faucett Associates, Regional Economic Effects of Highway Investment--A Case of the Interstate System (1971); Karen Polenske and P. Levy, Multi-Regional Economic Impacts of Energy and Transport Policies (Office of Transport Planning Analysis, 1975); and Benjamin H. Stevens et al., Regional Economic Analysis for Transportation Planning, NCHRP Report 8-15A, Regional Science Research Institute, 1982. 3. Gale Lang et al., "A Corridor Land Use Study: The Impact of an Interstate Highway on Land Values, Private Investment and Land Use in Southwestern Wyoming" (University of Wyoming, Laramie, 1970): Robert D. Sanders, The Economic Impact of Interstate Highway 35 on Towns in North Central Oklahoma (Oklahoma Department of Highways, 1973); and Robert W. Vockrodt, The Economic Effects of Interstate 94 on Truck Highway 10 Communities (Minnesota Department of Highways, 1972). 3 studies occurred a decade ago, and found very mixed evidence concerning whether or not there is any statistical or causal relationship between regional economic growth and highway improvements. They generally conclude that many other local factors besides highway improvements come into play to affect regional growth. Thus, all that can be concluded from these studies is that a new or substantially upgraded highway may or may not have economic impacts, depending on where it is located and the intercity connections it provides. Discussions with business executives who make location decisions, and economic development professionals involved in trying to attract businesses, however, provide evidence that highway issues are prominent in the expansion and location decisions of many firms. Surveys of corporate executives by Dow Jones & Co. and Site Selection magazine, for instance, have consistently found highway access to be one of the top three locational considerations for corporate headquarters, regional offices, research and development facilities, manufacturing plants and distribution centers. Overall; past research provides backing for the assertion that major highway improvements can have significant economic development benefits, although the magnitude of those benefits will vary depending on the particular setting and types of highway improvements being considered. Economic Development Benefits Whenever a section of highway is improved, individual auto and truck travelers benefit in terms of travel time, transportation cost and accident reduction. These are the direct user benefits, which have been the traditional means of determining benefits of a highway project. Direct user benefits for trucking can translate into real dollar savings for businesses that ship items by truck. However, highway improvements can have a significant impact on the corridor and state economy, over and above direct user benefits. Specifically, by reducing truck shipping costs, a very real efficiency benefit can accrue to the business shipping out the product, and a potential cost savings can accrue for the business receiving the product. Cost savings can mean lower product costs, which in turn can make local area businesses more competitive compared to their outside competition, and better able to expand to new markets. In addition to the business expansion benefit related to trucking cost savings, highway improvements can extend the market area that businesses can serve, as well as the areas from which they can access suppliers. They can extend the distance range accessible within a day's drive for truck deliveries or customer visits. They also can extend the distance range over which local businesses effectively compete with their counterparts located out of state (and vice versa). The extent of such benefits depends critically on the relative locations of business buyers, suppliers and competitors. These travel range impacts can provide opportunities for significant expansion and attraction of manufacturing and distribution industries. Consumer market areas for retail and service businesses are also affected by changes in effective trade areas, but those effects tend to be merely localized shifts in retail activity rather than true gains for the region and state as a whole. There can be additional impacts on the attraction of new business. In the case of the Wisconsin Highway Study, some types of businesses would find the corridor to be an attractive location if it were not for its lack of a four-lane, east-west highway. Some businesses not previously attracted to the area could also be lured if they were to see the area upgraded to be fully served by four-lane freeway or expressway facilities, providing fast and reliable transportation links to the national 4 highway network, regional population centers and specific buyers or suppliers. Improvements to this particular corridor could also enhance the perception that North-Central Wisconsin is an attractive place to live and locate a business. These types of impacts of highway upgrading are over and above incremental effects of travel time savings alone. Some types of businesses could find the proposed highway improvements to be necessary but not sufficient to attract them to the area. Some businesses could be attracted to the area if the highway improvements were to be accompanied by other economic incentives and/or public improvements, as part of an effort to address a broader set of what those businesses see as local or regional deficiencies in resources and services available. For this reason, the economic attraction benefits of each alternative must be viewed in the broader context of existing marketing and business development efforts at the local, regional and state levels. Tourism-related business is a special type of opportunity, whereby passenger travel benefits can lead to additional visitation to the state. For instance, given the location of Highway 29, four-lane improvements to it can provide a particular opportunity to make vacation and recreation areas along the Lake Michigan shore more accessible and attractive for Minnesota residents. The easier and more relaxed quality of travel experience along a four-lane freeway or expressway, in addition to safety and travel time benefits, can affect these tourism and recreational travel patterns. The economic development effects of highway improvements do not end with the direct effects on business expansion and attraction. There are also very significant spillover effects on the rest of the area economy. The direct effect on business expansion and attraction leads to indirect effects in terms of additional orders for materials and equipment from other businesses. For instance, expansion of the food processing industry would lead to expanded orders for plastic packaging and cardboard boxes. In addition, there are induced effects that result when new and expanding businesses hire more workers, who then spend money on consumer products and services. While businesses within the highway corridor study area are the principal beneficiaries of the direct benefits, the spillover indirect and induced business growth can provide very real benefits for the rest of the state. Appropriate Measures of Benefits Economic growth can be viewed as bringing more business sales, more jobs, more personal income and more population growth to the state. Such economic growth is publicly perceived as desirable insofar as it leads to greater employment opportunities, greater variety of shopping merchandise and cultural activity, higher income levels, a more vibrant atmosphere for private business investment and greater public resources for investment in local infrastructure. Impacts can be measured in terms of jobs, business sales or personal income. For cost-benefit analysis of Wisconsin highway projects, the disposable personal income measure is the appropriate measure of benefit for Wisconsin residents. The business sales measure includes benefits that go to out-of-state residents. For instance, fuel sales include the cost of Middle Eastern and South American petroleum. Personal income includes only the additional income to Wisconsin residents involved in the local sales, distribution or manufacturing of the product. Disposable 5 income further deletes the portion of personal income that is paid out in taxes, the majority of which goes to the federal government. There are other financial impacts of economic growth in addition to those associated with job creation, business sales and personal income. Economic growth can also lead to impacts on investment in industrial, commercial and residential land development, and hence property values. It would also be expected to bring about changes in local government revenues and expenses. These types of impacts tend to vary considerably by locality. Major new highway facilities and changes in economic growth can also bring localized changes in environmental conditions and quality of life, as a result of shifts in traffic patterns, shifts in shopping patterns and shifts in land use and development patterns. While highway projects can provide potential benefits for many different groups, and those benefits can be seen in many different ways, it is not appropriate to consider all of these different forms of benefits in a cost-benefit analysis, since it would be double counting to add together what are really the same fundamental benefits showing up in several different ways. For instance, property value increases can be the direct result of business growth and the increasing demand for property. Business growth changes, in turn may be partly the result of changes in relative business cost, which in turn may reflect changes in travel time and operating cost. For this study, all user benefits associated with trucking travel time, cost and safety improvements are incorporated in the measures of impacts on business expansion and attraction, and resulting disposable personal income benefits to state residents. The economic benefits are, in fact, greater when measured this way than when accounted for as simple user benefits. In the economic model, the additional income associated with business expansion is itself greater than the direct value a user benefits for existing truck travel. Similarly, the additional income associated with new business attraction is greater than the direct value of user benefits associated with the induced increment of truck travel. For purposes of completeness in the cost-benefit analysis, all impacts related to value of time savings, out-of-pocket costs and safety for auto travelers are also calculated, but no economic development benefits are calculated beyond the user benefits. All economic benefits in the costbenefit analysis are presented in terms of the discounted present value of the stream of additional disposable income over the 1990-2020 period. Analysis Methods Evaluation of economic development benefits involved several analysis techniques: · a computerized traffic simulation model of the entire state, sensitive to traffic distribution impacts and measurement of savings for area travelers; · a detailed economic forecasting and simulation model of the study area and state economy, sensitive to business growth impacts of changes in transportation costs; · an industry "screening" analysis process for identifying new business attraction impacts, sensitive to transportation impacts on interindustry sales and supply patterns; and · a tourism market forecasting process, sensitive to relative differences in travel time among competing areas. 6 The integrated design of the traffic and economic model system used in this study is of particular note. A highway network model was used to estimate impacts on traffic, distribution and travel times. These travel time changes were then input into the economic simulation model to estimate long-term impacts on population and employment growth. The forecast changes in population and employment were, in turn, used to estimate future changes in passenger and truck traffic for the highway model. This ability for interplay of traffic and economic models provided a means for ensuring consistency and recognizing interrelationships between traffic and business growth impacts. The transportation and economic models as well as the methodology for applying these models, and the analytic processes used for business attraction and tourism forecasts are discussed below. Transportation Model User benefits refer to the savings in travel time and out-of-pocket cost and safety associated with highway improvements. User benefits traditionally have been calculated for both autos and trucks and then combined to provide a total measure of direct benefits. For this study, however, truck benefits were separated from auto benefits and included as a basis for analysis of some economic development benefits, in the form of business expansion and new business development. Although trucking cost savings were initially estimated using the traffic model analysis of benefits, they were used as an input into the economic impact model, rather than being directly used in the costbenefit evaluation. Estimation of user benefits for each highway alternative was based on the output of a trip generation and route assignment travel model. The basis of the traffic forecasting was an urban transportation planning system network representation of the current and expected future statewide highway system. Using origin-destination studies and traffic counts, these models simulated current traffic volume and travel patterns. Population and employment projections were used to forecast trip patterns and future traffic separate from any improvements to the corridor. Once no build conditions were estimated, the models simulated new traffic and travel patterns expected under each improvement alternative. In addition to the increase in normal traffic growth (expected from changes in population, employment and auto use), the models were used to estimate how alternative highway improvements would attract trips from nearby routes, thus further increasing traffic volume. The assignment of traffic onto the most efficient route linking origins and destinations on the system produced a different distribution of trips for each alternative. With each successive level of improvement, the corridor was forecast to attract more and more traffic from other routes previously used by travelers. Figure 2 shows how each higher improvement level extends the area of influence (i.e., area of origins and destinations for which it would serve) of the improved highway. 7 Figure 2. Highway 29/45 corridor area of influence The end product of the simulation process of all highway use was an accumulation of all highway use assigned to individual portions of the statewide highway network. Based on these assignments, miles traveled and hours spent were totaled for trips between all locations on the network. These miles and hours were related to safety, time, and operating costs and thus used as the foundation for calculating auto and truck user benefits for each improvement alternative. Automobile user benefits were calculated assuming a value of time of $7/hour passenger vehicles, and value of accident reduction based on "willingness to pay" studies sponsored by the Federal Highway Administration and conducted at the Urban Institute. Results of the auto user benefit analysis showed that a freeway produces the greatest absolute benefits, as time savings and accident reduction benefits more than offset the growing operating costs that result from higher speeds on the freeway. 8 Economic Model Direct truck cost savings can lower business cost of acquiring supplies and/or distributing products, thus making local businesses more cost competitive and able to expand relative to out-ofstate competition. This impact is estimated by examining current relative costs of doing business in the study area compared to elsewhere (for each industry), and by considering how reductions in relative business costs lead to expansion in relative rates of business growth (for each industry). Traditional economic analysis techniques fall short here. The traditional approach uses an inputoutput model to estimate indirect and induced growth of the area economy, given a direct change in jobs and business sales that the highway creates. What it does not predict is how highway improvements will change the competitive position of different types of businesses, and how that competitive change will directly affect future business growth. To address such issues, the regional economic forecasting and simulation model (Regional Economic Models, Inc.-REMI) was created. The Wisconsin Forecasting and Simulation Model is a statewide REMI model used for the past several years by the Wisconsin Department of Development. A special multi-area version, specifically designed for counties within the study area, was applied for this study. Essentially, the model predicts, for each year in the future, the number and distribution of income, output and employment in each substate area for each industry sector and each occupational category. Sub-state areas are defined as five sub-zones within the project study area, plus a sixth zone comprising the rest of the state. The REMI simulation model and conjoined input-output model provides information on business output and employment in terms of 490 detailed industry sectors and 94 detailed occupational categories. The model process is outlined in Figure 3. One basis for the REMI model was a set of information on the specific industrial structure of the state in terms of inter-industry purchasing patterns. This is the information that comes from input-output accounting tables, which trace the extent to which each industry sector generates demand for inputs from other sectors. The REMI model, however, goes far beyond simple input-output accounting by incorporating information on a large number of policy-sensitive economic factors and relationships, in terms of how they change the region's economic growth or decline by industry sector. They include effects of transportation costs, as well as costs of labor, equipment, materials, capital financing and taxes. In each case, the REMI model evaluates cost of doing business for each industry sector, comparing costs for businesses within the study area with costs for similar business located elsewhere. The forecast of future business growth and decline in each area is then made on the basis of (1) national forecasts for change in each business sector and their technologies of production; (2) differences in relative costs of production in each business sector within the study area, compared to elsewhere in the nation; (3) expected change in transportation and production cost in each business sector resulting from the highway projects; and (4) expected change in attraction of business from out of state, and tourists from out of state. 9 Figure 3. REMI forecast National Forecast Industry Growth/Decline National Data Wisconsin Economic Mix Wisconsin Performance Relative to US I-O Related Analysis Wisconsin Economic Structure: Import, Export, Inter-Industry Flows Structural Policy Model Relative Cost of Doing Business: Affecting Economic Growth IMPACT FORECASTS 10 • Fuel • Taxes • Capital Costs • Labor Costs • Transport Costs • Labor/Capital Intensity ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY AND FINDINGS Economic impacts of highway improvements could be increased or lessened by future changes in the area's business mix, which will affect relative reliance on trucking. In addition, economic impacts could also be affected by future changes in technologies affecting interindustry shipping relationships. For the study area, the REMI forecasts indicated that output of three major industries-paper, food products and health care-will grow at a slower pace and actually decline in employment compared to the past decade. These patterns, which hold for both the study area and the rest of the state, are due, in part, to the expected slowdown in the rate of growth of the state's population and economy. They are also due to forecasts of continued technology change, raising the output per employee over the long-term 1986-2020 period. In fact, both the paper and food industries are also undergoing significant changes in product mix. In the paper industry, converted paper products are forecast to grow, while production of paperboard containers are not. In the food industry, frozen foods are forecast to grow, while output of dairy products are not. These changes in industrial mix were forecast to have a bearing on highway impacts because surveys showed that each type of industry had a very different shipping pattern. In order to estimate the magnitude of trucking-related benefits to business, a three-step process was used. The first step was to conduct a series of surveys to profile truck shipping patterns and current truck reliance on Highways 29, 45 and 10. The next step was to estimate the business cost savings of proposed highway improvements, based on truck shipping patterns and the cost structure of different types of businesses. The final step was to estimate impacts of these cost savings on business expansion rates. This process made use of the REMI economic forecasting model, which relates changes in business costs of truck shipments to competitive cost of doing business, comparing businesses in the study area, rest of the state, adjoining states and rest of the country. A mail-back survey of area firms provided information on the overall pattern of truck trips originating in or destined for locations within the study region. The survey showed differences in industry supplier-buyer locations among types of businesses, and these were reflected in their truck shipping patterns. These patterns of interstate travel are shown in Figure 4 for four major industries in the study area. The survey also showed systematic differences in truck shipping patterns among sub-zones of the study corridor (see Figure 5). 11 Figure 4. Inter-state trucking patterns for selected industries by zone of origin/destination Figure 5. Intra-state trucking patterns (all industries) by zone of origin/ destination 12 The cost savings for truck movements was then calculated on the basis of changes in travel time and operating costs for current users, forecast new users and diverted trips under each highway improvement alternative. The effect of a truck shipment cost savings on the competitive position of businesses depends on the importance of truck costs as a component of the total cost of doing business. There are many components of overall business cost, including labor, capital equipment, utilities, depreciation, financing costs, etc. Truck shipping costs include costs of businesses purchasing services from the trucking industry and costs of businesses doing their own shipping (including truck driver labor costs). Businesses found to be most sensitive to truck shipping costs are trucking firms, petroleum product firms, and paper manufacturers. The overall economic impacts reflect expansion of businesses benefiting from trucking cost savings (direct effects), plus expansion of their business suppliers (indirect effects) and expansion of other businesses receiving additional worker spending (induced effects). While the directly benefiting businesses are largely manufacturing, distribution and trucking firms, the indirect and induced benefits also involve retail, wholesale and service businesses. The analysis of truck travel concluded that total benefits to existing business are greater for freeway and freeway/expressway alternatives than for the base case. However, improvements beyond the freeway/ expressway II alternative yielded no further increase in truck cost savings, because the time savings from further speed increases were cancelled by the lower fuel economy and higher vehicle operating costs that occur when trucks travel faster than 55 mph. Business Attraction Impacts While trucking cost savings themselves can lead to business growth, there are other ways in which highway improvements can affect the attractiveness of the corridor as a place to do business. The area might become more attractive to new businesses because of the geographic positioning of the highway relative to locations of particular population centers, suppliers or buyers (both in-state and out-of-state), providing special opportunities for particular combinations of industries to better support each other and take advantage of emerging technologies or provide new products, or its impacts through improving the perceived quality of life of the region served. These are additional business attraction impacts, over and above the truck cost saving impacts. Estimation of the impact on business attraction of the proposed improvements to Highways 29 and 45 required a three-phased methodology. First, a list of industries compatible with the corridor economy and resources available was compiled. Second, characteristics of those industries-and the comparative cost of business operations in Wisconsin and the corridor-were evaluated to determine whether or not these types of businesses would find the area cost competitive to be attracted to the region. Third, business attraction and job creation potentials were distinguished in terms of whether they required: 1. only highway improvements to be made; 2. other economic development or business attraction factors aside from highway improvements; or 13 3. both highway improvements and attention to other economic development or business attraction factors. As a first step in identifying industries that might be attracted to the study area as a result of the highway improvements, economic development agencies and chambers of commerce within' the study area were contacted. These organizations were asked to list current business attraction targets and reasons for these targeting efforts. To further identify industries that might be attracted as a result of the highway improvements, the existing economic base and regional characteristics were examined to identify potential linkages between existing industries, natural resources, universities and technical schools, labor force, etc., and industries that are currently not located in the study area. In addition, interviews were conducted with representatives of individual businesses and trade associations to identify the most important locational characteristics considered when making facility location decisions. These industry specialists were further asked to evaluate the importance of highway access to their location decisions, and the appeal of central Wisconsin locations. The competitive position of the corridor study area for attracting target industries was also evaluated in terms of relative costs for fuel, capital and labor in the study area, compared to the same cost factors for the rest of Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the United States as a whole. The existing concentration of each industry in the study area was also compared to the concentrations in those comparison areas. This was used to identify the types of businesses thriving nearby, although currently underrepresented in the study area. Finally, because highway improvements would improve accessibility through the region, potential negative impacts of businesses attracted out of the region were also taken into account. The analysis concluded that the greatest business attraction expected to occur as a direct result of the highway improvements was in the Northeast area of the corridor, followed by the Central and East (Fox Valley) areas. Essentially no further business attraction benefits were expected for the West or Lakeshore areas. Key beneficiary businesses were forecast to be specialized paper products, printing, food products and wood products. Compared to the full freeway, the two freeway/ expressway alternatives and the base case were found to have a lesser benefit, since both have at-grade intersections, foregoing the "interstate quality" freeway access that some businesses look for in their location decisions. The business attractive analysis concluded that while highway improvements alone can enhance the attractiveness of the region to attract investment for business location and expansion, these positive impacts can be even larger if coupled with business marketing and economic development programs. Tourism Benefits Business impacts of the proposed highway improvements will extend beyond trucking firms and businesses that ship or receive goods by truck. In fact, one industry that is expected to be a major beneficiary of any of the proposed highway improvement alternatives is the tourism industry, which serves both business and recreational travel. 14 Tourism benefits occur insofar as the highway improvements lessen travel time, reduce safety hazards and make travel more enjoyable for trips to various tourist destinations and recreational attractions within Wisconsin. Tourism benefits occur principally due to greater visitation and spending by out-of-state visitors. Shifts among in-state visitor destinations are of no economic benefit to the state. . The methodology for deriving the impact of proposed highway improvements on tourism included two key steps. The initial part of the tourism impact analysis was to estimate baseline tourist and visitor activity in the area. Baseline data was then refined to estimate the number of visitors to each zone that used Highways 29, 45 and 10. Visitor spending associated with use of these highways was calculated based on prior surveys of typical spending levels by different types of visitors. The second part of the analysis was to determine the potential impact on visitation patterns resulting from the proposed highway improvements. The findings drew heavily on responses to interviews with owners and managers of hospitality, tourism and recreation businesses and promotional organizations within the study area. It drew upon their own evaluations of existing and potential market attraction characteristics, competitive position relative to competing attractions, travel distances and spending patterns. The assessment distinguished new tourist trips generated or attracted from out of state, and new tourist trips which are merely transfers of trip destinations from one part of Wisconsin to another. Overall, the study concluded that the Lakeshore and Northeast areas would be expected to realize the greatest absolute increase in visitor days and dollars spent by tourists. The concentration of tourism impact on these two regions occurred because both have major regional and super-regional tourist destinations with the potential to attract additional visitors from the Twin Cities and the rest of Minnesota. OVERALL BENEFITS AND COSTS The cost-benefit evaluation is a comparison of benefits and costs associated with each of the four highway improvement alternatives, relative to the no build scenario. The comparison is made in terms of net benefit (defined as benefits minus costs) and B/C ratio benefits divided by costs). The set of costs considered for each alternative include estimates of all right-of-way acquisition and construction-related costs plus all ongoing rehabilitation and maintenance costs. The set of benefits considered include user benefits to auto travelers plus estimates of long-run (after construction) economic development impacts, including those resulting as an outcome of truck user benefits: Construction period benefits are explicitly ignored for purposes of the cost-benefit analysis, due to the nature of the investment decision-making. Highway construction expenditures associated with the project provide very real benefits in terms of business sales, income and jobs created. However, these dollars are assumed to be funds that would have been spent anyway by state government-if not on this project, then on other highway or public works investments with comparable capital expenditure benefits. For this reason, the short-term benefits associated with 15 construction spending are not relevant as additional benefits for purposes of ranking the project alternatives. The long-term transportation efficiency and economic development benefits associated with the project are measured by comparing statewide levels of income and jobs that would exist with and without each of the alternatives for proposed highway improvements. This is a clear and straightforward way of assessing project impacts on the state economy. The streams of benefits and costs over time are assessed in terms of their "present value," which discounts benefits and costs expected to occur further off in the future. Another issue, which can then be raised, is whether funding of the Highway 29/45/10 project actually causes other socially beneficial but competing projects (or other public expenditures) to be foregone. If so, it could be argued that the potential benefits of those foregone projects represent an additional "opportunity cost" associated with the Highway 29/45/10 project. In fact, it is clearly premature and inappropriate to guess how the proposed project will be financed, whether it be federal grants or new taxes or allocations from existing departmental budgets or other sources. Hypothetical competing alternatives need not be considered if the study objective is to evaluate highway improvement alternatives relative to each other, and not relative to all possible alternative expenditures. Project Benefits Economic development benefits are classified in terms of business expansion induced by cost savings, additional business attraction and increased tourism. User benefits for truck users are not counted in this benefit assessment since they are encompassed within the greater measure of business expansion benefits. Auto user benefits are estimated on the basis of a valuation of travel time savings, operating cost changes and accident rate reduction benefits. The present value of all economic development and auto user benefits (compared to the do nothing alternative) is shown in Table 2. There are several notable aspects of these numbers and their components. One is that economic development impacts account for roughly half of the total benefits. (It varies from 42 percent to 52 percent depending on the highway improvement alternative.) This is particularly notable since trucks account for just 20 percent of the traffic on Highways 29, 45 and 10. A second observation is that the spread in economic development benefits between the freeway and base case alternatives is nearly twice as large as the corresponding spread in auto user benefits for the same alternatives. There are several reasons for this. One is that the computation of economic development benefits includes a large reduction in industry and tourism attraction for the base case alternative where less than a fully four-lane expressway is provided. The other is that auto user benefits do not increase proportionally to speed increases and travel time savings for the higher level improvement alternatives, due to offsetting impacts of greater fuel consumption and increased auto operating costs at higher speeds. In fact, the penalty of higher operating costs at higher speeds causes the freeway/ expressway I alternative to have slightly lower auto user benefits than the lower speed freeway/ expressway II alternative. 16 TABLE 2-PRESENT VALUE OF COSTS AND BENEFITS OF HIGHWAY IMPROVEMENT ALTERNATIVES (Present value of 1990-2020 Disposable Income Benefits in Millions of 198'7 Dollars, Compared to the "No Build" Alternative) Freeway/ Freeway/ Exprezs- Base Freeway Expressway way 11 Case Costs Present value of total cost 29/45 (Compared to no build) 29/ 10 Economic development benefits (trucks) (disposable income value) Expansion due to truck cost savings 29/45 29/10 Additional industry attraction 29/45 29/10 Increased tourism 29/45 29/10 Subtotal: economic development benefits 29/45 29/10 Auto user benefits (autos only) (income equivalent value) Value of auto travel time savings 29/45 29/10 Change in auto operating costs 29/45 29/10 Value of auto accident reduction benefits 29/45 29/ 10 Subtotal: auto user benefits 29/45 29/10 Present value of total benefits 29/45 29/10 $550 564 $447 415 $334 337 $225 250 164 168 218 246 56 55 $438 469 164 168 164 184 42 _41 $370 393 164 168 153 172 39 _39 $356 379 131 132 55 62 14 _14 $200 208 $385 356 - 115 -116 138 146 $408 386 $846 855 $305 288 -46 -39 103 _123 $362 372 $447 765 $296 287 -13 -12 98 _107 $281 382 $334 761 $218 200 7 4 56 _67 $281 271 $225 479 Project Costs Costs associated with each highway improvement alternative include construction costs over 19891999 period, plus rehabilitation and general maintenance costs over the entire 1989-2020 time period. All costs are shown over and above those for the no build alternative, which includes costs of pavement maintenance. Benefit-Cost Comparison Table 3 compares the benefits and costs of each of the four highway improvement alternatives for both the 29/10 route and the 29/45 route. The benefit/cost ratio measures the efficiency of 17 spending in terms of return on investment. It clearly indicates that the Highway 29/10 freeway/expressway II alternative provides the greatest benefit/cost ratio. It returns $2.30 of benefit for every dollar spent on the highway. Of course, not all of these benefits represent dollars added to the economy. In fact, half of the benefits from the Highway 29/10 freeway/ expressway II alternative are in the form of auto user travel time and safety benefits. TABLE 3--COMPARISON OF BENEFITS AND COSTS (Present Value of 1990-2020 Benefits and Costs, in Millions of 1987 Dollars, Compared to the No Build Alternative) Present value of total benefits Present value of total costs Benefit/cost ratio Net benefit (benefit-cost) Freeway Freeway Freeway/ Express- Freeway/ Base Expressway Way I Express-II Case 29/45 29/10 29/45 29110 29/45 29/10 29/45 29/10 $846 $855 $550 $564 1.5 1.5 $296 $291 $732 $765 $447 $415 1.6 1.8 $285 $350 $737 $761 $334 $337 2.2 2.3 $403 $424 $481 $479 $225 $250 2.1 1.9 $256 $229 Another measure is the net benefit, calculated as benefits minus costs. The Highway 29/10 freeway/ expressway II alternative also provides the greatest net benefit, which has a present value benefit of $424 million over costs. Thus, the freeway/expressway II alternative for the Highway 29/10 route emerges as clearly the most beneficial, providing greater benefits than that same alternative using the Highway 29/45 route. CONCLUSIONS The Wisconsin study demonstrates how economic development benefits of highway projects can be estimated, and those estimates used for benefit-cost analysis to support policy decision-making. The state of Wisconsin has adopted and started to implement the highway alternative recommended by this study. However, this study also shows that a full evaluation of economic development benefits can be complicated, requiring a set of separate analytic techniques for estimation of impacts on relative business costs, business attraction and tourism, as well as modeling of travel patterns and regional economics. 18