Steps to a Healthier US Workforce:

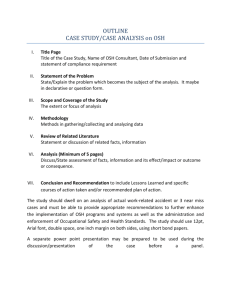

advertisement