Literatures of the Great War Term 2, Week 8

advertisement

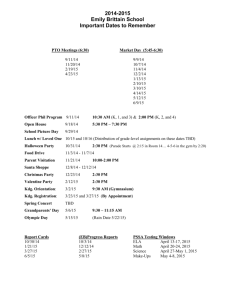

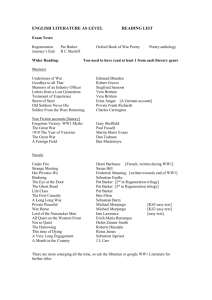

Literatures of the Great War Term 2, Week 8 English Memoirs Testament of Youth ‘[D]rawing a picture of middle-class England – its interests, its morals, its social ideals, its politics – as it was from the time of my earliest conscious memory, and then telling some kind of personal story against this changing background’ (TY, Foreword, p. xxv). ‘[T]o tell my own fairly typical story as truthfully as I could against the larger background, and take the risk of offending all those who believe that a personal story should be kept private, however great its public significance and however wide its general application’ (TY, Foreword, p. xxvi). ‘[Brittain] confessed to a male associate who traveled in similar literary circles that she was working on “a kind of autobiography”. This fellow writer greeted Brittain’s admission with contempt and remarked: “An Autobiography! But I shouldn’t have thought that anything in your life was worth recording!”’ (Richard Badenhausen, ‘Testament of Youth’, Twentieth Century Literature, 49: 4 (Winter, 2003), 421-448 (p. 421)) Brittain at Melrose, the family home, in Buxton, 1913 Edward Brittain, Roland Leighton and Victor Richardson in Officers Training Corps uniform, Uppingham, 1914 Edward Brittain Roland Leighton Vera Brittain Geoffrey Thurlow Victor Richardson The Galeka The Britannic Imtarfa Military Hospital, 1917 Brittain at Nurses' Quarters, St George’s Hospital, Malta, c.1916 Brittain with patients, St George’s Hospital, Malta, 1916 Brittain (third from left) and colleagues, Near St George's Hospital, Malta, c.1917 Part of hospital complex at Étaples WAACs tending graves at Étaples Testament of Youth ‘[Brittain] builds the text around her letters to Roland Leighton, her brother Edward, & others, as well as letters from those correspondents […] the memoir is thus overrun with different types of writings, including selections from her diaries; epigraphic poems by herself and Leighton at the head of chapters; literary quotations within the body of chapters from renowned writers like Shelley, Wordsworth, Brooke, Longfellow, Hardy, and Kipling, as well as from more minor figures; popular verses from English newspapers; the texts of posters and placards; the words, and sometimes even music, to various songs and marches; excerpts from sermons, prayers, news headlines & stories, introductions to textbooks, & book reviews; and even scraps of odd documents like “a few pages torn from a child’s exercise-book that [Leighton] had found in a ruined house, and appeared to contain some stumbling translations from Flemish into French”’ (Badenhausen, p. 438). VB thus ‘create[s] a communal conversation about the trauma […] The [epigraphic] poems foreground an earlier, untraumatized version of herself, and the prose chapters write against that voice’ (Badenhausen, p. 439). Testament of Youth ‘Testament directly reproduces some of the less palatable ideologies that helped to make the VAD institution successful. Katharine Furse, the director, played the class and educational high standards of the applicants as a trump card against possible accusations on the part of the military of “unladylike” behaviour. The result was that not only were women of lower social status excluded from nursing service, but that they were also encased in an ideological construct that assumed their moral inferiority. Brittain maintains the discourse of superior sensitivity, and even uses it to derogate the trained nurses, whom she constructs as envious of the innate capabilities of the volunteers and, in any case, intrinsically dull. The literary effect of Brittain’s text has been to promote and validate the woman’s story of the war. Its political effect has been, in its silent reproduction of the ideologies exploited by Furse to ensure women’s acceptance near the trenches, to advance a feminism predicated on an individualism that was available only to women of a certain class.’ (Sharon Ouditt, Fighting Forces, Writing Women: Identity and Ideology in the First World War (London: Routledge, 1994), pp. 3–4) Testament of Youth Some approaches • ‘[A]utobiographical study’? • Responsibilities to others’ privacy & sensibilities? • Social context Middle-class society Women’s experience • Hindsight/later commentary • New approach to familiar themes Lack of information; rumour Propaganda Non-participants Lost generation • Narrator reliable or unreliable? • Relation to fiction (dramatic/literary effects &c