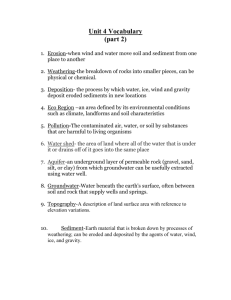

Role of Mycorrhizae in Rhizosphere Processes and Phosphorus Dynamics

advertisement