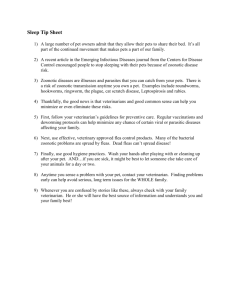

Household Pets and Zoonoses Summary

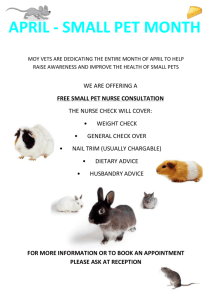

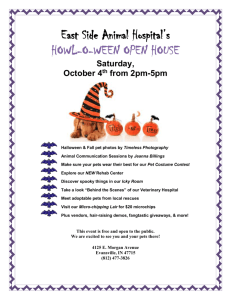

advertisement