National Arthritis Action Plan: A Public Health Strategy

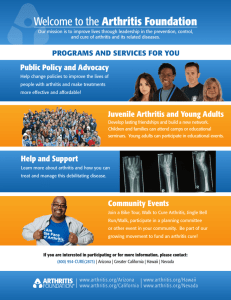

advertisement