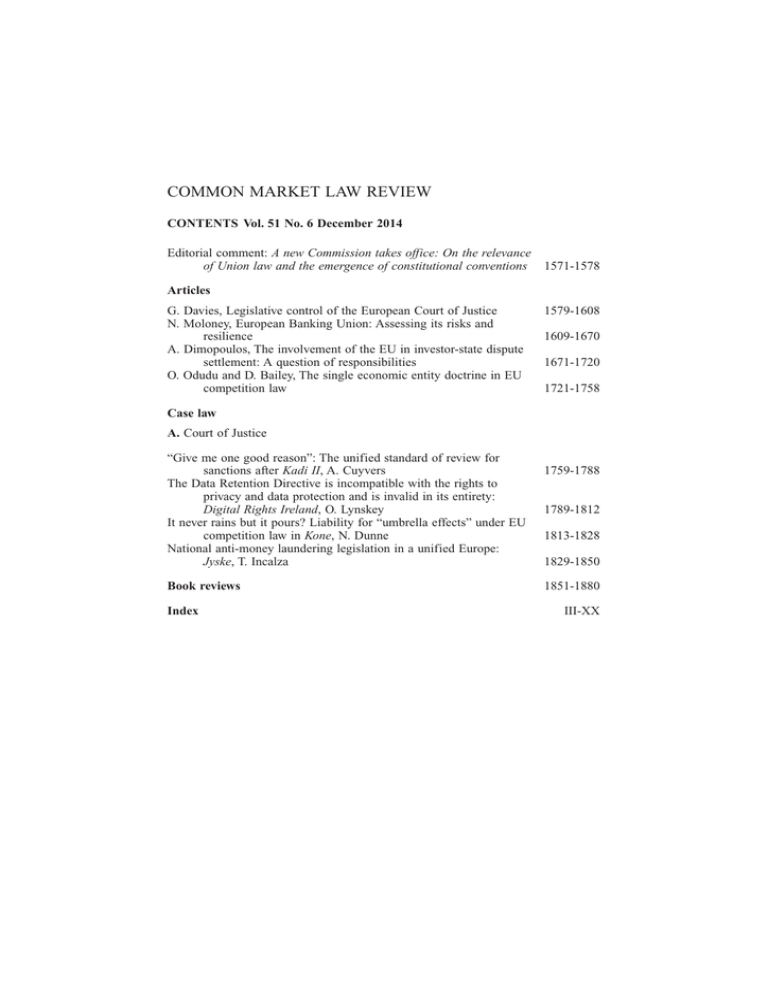

COMMON MARKET LAW REVIEW

CONTENTS Vol. 51 No. 6 December 2014

Editorial comment: A new Commission takes office: On the relevance

of Union law and the emergence of constitutional conventions

1571-1578

Articles

G. Davies, Legislative control of the European Court of Justice

N. Moloney, European Banking Union: Assessing its risks and

resilience

A. Dimopoulos, The involvement of the EU in investor-state dispute

settlement: A question of responsibilities

O. Odudu and D. Bailey, The single economic entity doctrine in EU

competition law

1579-1608

1609-1670

1671-1720

1721-1758

Case law

A. Court of Justice

“Give me one good reason”: The unified standard of review for

sanctions after Kadi II, A. Cuyvers

The Data Retention Directive is incompatible with the rights to

privacy and data protection and is invalid in its entirety:

Digital Rights Ireland, O. Lynskey

It never rains but it pours? Liability for “umbrella effects” under EU

competition law in Kone, N. Dunne

National anti-money laundering legislation in a unified Europe:

Jyske, T. Incalza

1789-1812

Book reviews

1851-1880

Index

1759-1788

1813-1828

1829-1850

III-XX

Aims

The Common Market Law Review is designed to function as a medium for the understanding and

implementation of European Union Law within the Member States and elsewhere, and for the

dissemination of legal thinking on European Union Law matters. It thus aims to meet the needs of

both the academic and the practitioner. For practical reasons, English is used as the language of

communication.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, without prior written permission of the publishers.

Permission to use this content must be obtained from the copyright owner. Please apply to:

Permissions Department, Wolters Kluwer Legal, 111 Eighth Avenue, 7th Floor, New York, NY

10011–5201, United States of America. E-mail: permissions@kluwerlaw.com.

Common Market Law Review is published bimonthly.

Subscription prices 2015 [Volume 52, 6 issues] including postage and handling:

Print subscription prices: EUR 802/USD 1134/GBP 572

Online subscription prices: EUR 758/USD 1075/GBP 544

This journal is also available online. Online and individual subscription prices are available upon

request. Please contact our sales department for further information at +31(0)172 641562 or at

sales@kluwerlaw.com.

Periodicals postage paid at Rahway, N.J. USPS no. 663–170.

U.S. Mailing Agent: Mercury Airfreight International Ltd., 365 Blair Road, Avenel, NJ 07001.

Published by Kluwer Law International, P.O. Box 316, 2400 AH Alphen aan den Rijn,

The Netherlands

Printed on acid-free paper.

COMMON MARKET LAW REVIEW

COMMON MARKET LAW REVIEW

Editors: Thomas Ackermann, Loïc Azoulai, Michael Dougan, Christophe Hillion,

Siofra O’Leary, Wulf-Henning Roth, Ben Smulders, Stefaan Van den Bogaert

Subscription information

Online subscription prices for 2015 (Volume 52, 6 issues) are: EUR 758/USD 1075/

GBP 544. Print subscription prices for 2015 (Volume 52, 6 issues):

EUR 802/USD 1134/GBP 572

Personal subscription prices at a substantially reduced rate are available upon request. Please

contact our sales department for further information at +31 172641562 or at sales@kluwerlaw.

com.

Advisory Board:

Ulf Bernitz, Stockholm

Kieran Bradley, Luxembourg

Alan Dashwood, Cambridge

Jacqueline Dutheil de la Rochère, Paris

Claus-Dieter Ehlermann, Brussels

Giorgio Gaja, Florence

Walter van Gerven, Leuven

Roger Goebel, New York

Daniel Halberstam, Ann Arbor

Gerard Hogan, Dublin

Laurence Idot, Paris

Francis Jacobs, London

Jean-Paul Jacqué, Brussels

Pieter Jan Kuijper, Amsterdam

Ole Lando, Copenhagen

Miguel Poiares Maduro, Florence

Sacha Prechal, Luxembourg

Gil Carlos Rodriguez Iglesias, Madrid

Allan Rosas, Luxembourg

Eleanor Sharpston, Luxembourg

Piet Jan Slot, Amsterdam

John Spencer, Cambridge

Christiaan W.A. Timmermans, Brussels

Ernö Várnáy, Debrecen

Joachim Vogel†, München

Armin von Bogdandy, Heidelberg

Joseph H.H. Weiler, Florence

Jan A. Winter, Bloemendaal

Miroslaw Wyrzykowski, Warsaw

Associate Editor: Alison McDonnell

Common Market Law Review

Europa Instituut

Steenschuur 25

2311 ES Leiden

The Netherlands

tel. + 31 71 5277549

e-mail: a.m.mcdonnell@law.leidenuniv.nl

fax: + 31 71 5277600

Aims

The Common Market Law Review is designed to function as a medium for the

understanding and analysis of European Union Law, and for the dissemination of legal

thinking on all matters of European Union Law. It thus aims to meet the needs of both the

academic and the practitioner. For practical reasons, English is used as the language of

communication.

Editorial policy

The editors will consider for publication manuscripts by contributors from any country.

Articles will be subjected to a review procedure. The author should ensure that the

significance of the contribution will be apparent also to readers outside the specific

expertise. Special terms and abbreviations should be clearly defined in the text or notes.

Accepted manuscripts will be edited, if necessary, to improve the general effectiveness of

communication.

If editing should be extensive, with a consequent danger of altering the meaning,

the manuscript will be returned to the author for approval before type is set.

Submission of manuscripts

Manuscripts should be submitted, together with a covering letter, to the Associate Editor.

At the time the manuscript is submitted, written assurance must be given that the article

has not been published, submitted, or accepted elsewhere. The author will be notified of

acceptance, rejection or need for revision within three to nine weeks.

Authors may be requested to submit a hard copy of their manuscript, in addition to a

digital copy, together with a summary of the contents. Articles should preferably be no longer

than 28 pages (approx. 9,000 words). Annotations should be no longer than 10 pages (approx.

3,000 words). The title of an article should begin with a word useful in indexing and

information retrieval. Short titles are invited for use as running heads. All notes should be

numbered in sequential order, as cited in the text, *Except for the first note, giving the

author’s affiliation.The author should submit biographical data, including his or her current

affiliation.

© 2014 Kluwer Law International. Printed in the United Kingdom.

Further details concerning submission are to be found on the journal’s website

http://www.kluwerlawonline.com/productinfo.php?pubcode=COLA

Payments can be made by bank draft, personal cheque, international money order, or UNESCO

coupons.

Subscription orders should be sent to:

All requests for further information

and specimen copies should be addressed to:

Kluwer Law International

c/o Turpin Distribution Services Ltd

Stratton Business Park

Pegasus Drive

Biggleswade

Bedfordshire SG18 8TQ

United Kingdom

e-mail: sales@kluwerlaw.com

Kluwer Law International

P.O. Box 316

2400 AH Alphen aan den Rijn

The Netherlands

fax: +31 172641515

or to any subscription agent

For Marketing Opportunities please contact marketing@kluwerlaw.com

Please visit the Common Market Law Review homepage at http://www.kluwerlawonline.com

for up-to-date information, tables of contents and to view a FREE online sample copy.

Consent to publish in this journal entails the author’s irrevocable and exclusive authorization

of the publisher to collect any sums or considerations for copying or reproduction payable by

third parties (as mentioned in Article 17, paragraph 2, of the Dutch Copyright act of 1912 and

in the Royal Decree of 20 June 1974 (S.351) pursuant to Article 16b of the Dutch Copyright

act of 1912) and/or to act in or out of court in connection herewith.

Microfilm and Microfiche editions of this journal are available from University Microfilms

International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106, USA.

The Common Market Law Review is indexed/abstracted in Current Contents/Social &

Behavioral Sciences; Current Legal Sociology; Data Juridica; European Access; European

Legal Journals Index; IBZ-CD-ROM: IBZ-Online; IBZ-lnternational Bibliography of Periodical literature on the Humanities and Social Sciences; Index to Foreign Legal Periodicals;

International Political Science Abstracts; The ISI Alerting Services; Legal Journals Index;

RAVE; Social Sciences Citation Index; Social Scisearch.

Common Market Law Review 51: 1671–1720, 2014.

© 2014 Kluwer Law International. Printed in the United Kingdom.

THE INVOLVEMENT OF THE EU IN INVESTOR-STATE DISPUTE

SETTLEMENT: A QUESTION OF RESPONSIBILITIES

ANGELOS DIMOPOULOS*

Abstract

This article discusses the legal framework for the involvement of the EU

and its Member States in Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) under

EU and Member State international investment agreements (IIAs). It

assesses whether the Financial Responsibility Regulation is a sufficient

and appropriate instrument to address the issue. It examines if and when

EU involvement in ISDS under EU IIAs is compatible with international

law and argues that EU IIAs and the Regulation should take into

consideration that international responsibility rules pose constraints on

the EU and Member State participation in ISDS, and that ICSID

arbitration can be a truly available ISDS option only if Member States can

act as respondents in all disputes concerning violations of EU IIAs. The

article then assesses the EU law implications of EU involvement in ISDS.

It explores the threats to the autonomy of the EU legal order; it examines

whether the allocation of financial responsibility is compatible with EU

rules on EU and Member State liability; it discusses how the application

and interpretation of the Financial Responsibility Regulation by the ECJ

may interfere with ISDS proceedings. Finally, it identifies the limited

scope for EU involvement in ISDS under Member State BITs, arguing that

the price that Member States have to pay for retaining their own

investment treaties is to bear full responsibility for all violations of their

BITs, even if they result from EU conduct.

1.

Introduction

In 2009 the Lisbon Treaty entered into force and endowed the EU with

exclusive competence over Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).1 Since then, the

EU has emerged as a new international actor in the field of foreign investment.

Already in 2010 the Commission made explicit its intention to create a

comprehensive EU investment policy by gradually taking over this field from

* Lecturer in Law, Queen Mary University of London. Websites were last visited 29 Sept.

2014.

1. Art. 207 TFEU together with Art. 3(1)(e) TFEU confer exclusive competence on the EU

in the field of the Common Commercial Policy, including FDI.

1672

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

Member States.2 Member State Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) amount

to more than 1,400 – which is slightly less than half of all existing BITs

worldwide.3 It is thus apparent why the EU can affect international investment

law.

One of the most controversial but least clarified aspects of the debate

concerns the involvement of the EU in investor-state dispute settlement

(ISDS). ISDS presents a unique system for dispute settlement under

international law involving individuals, and it has been an indispensable

characteristic of international investment agreements (IIAs). The growing

number of investment disputes and the million dollar awards rendered

annually by arbitral tribunals4 illustrate how successfully ISDS has been used

by investors to protect their interests, and why ISDS has been the source of

significant criticism, concerning mainly its legitimacy.5 Yet, the different

settings and the multifaceted nature of EU involvement in investment

arbitration create uncertainties. Indeed, the involvement of the EU in ISDS can

be very different depending on whether i) ISDS occurs under an IIA

concluded by the EU, the EU and its Member States together or its Member

States alone; ii) the dispute concerns a measure adopted by the EU, a Member

State acting within the scope of EU law, or a Member State acting on its own;

and whether iii) it concerns a dispute where third countries or their nationals

are involved, or only EU Member States and their nationals are involved. In

that respect, the clarification of the exact involvement of the EU in ISDS is

crucial for foreign investors, who need to know if ISDS is available for all of

the above situations and, if so, who can act as the respondent party in ISDS.

The position of third-country investors in the EU affects also indirectly the

interests of EU investors abroad, as most IIAs offer reciprocal rights to the

other party’s investors. In addition, the financial implications of ISDS require

a proper identification of whether and when the EU and its Member States

bear the costs of investment arbitration. Last but not least, the clarification of

the implications of EU involvement in ISDS is crucial for all adjudicatory

2. COM(2010)343, “Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European

Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions:

Towards a comprehensive European international investment policy”. <trade.ec.europa.eu/

doclib/docs/2010/july/tradoc_146307.pdf>.

3. UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2012: Towards a new generation of investment

policies” (2012) <www.unctad-docs.org/files/UNCTAD-WIR2012-Full-en.pdf>

4. UNCTAD, “Recent developments in investor-state dispute settlement”, (4 Apr. 2014),

<unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/webdiaepcb2014d3_en.pdf> .

5. On criticism of ISDS see indicatively Hachez and Wouters, “International investment

dispute settlement in the twenty-first century: Does the preservation of the public interest

require an alternative to the arbitral model?” in Baetens (Ed.), Investment Law within

International Law. Integrationist Perspectives (CUP, 2013), pp. 417–449.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1673

bodies, including EU courts and arbitral tribunals who will eventually be

called to decide on these matters.

The complexity of these questions has been in fact an important reason

preventing progress in the negotiations of IIAs by the EU (EU IIAs).6 Indeed,

the part on ISDS remains the main part of the investment chapter of the

EU-Canada CETA that is yet to be finalized,7 while the negotiations of the

ISDS provisions of the investment chapter of the Transatlantic Trade and

Investment Partnership (TTIP) agreement with the US have been postponed,

as the EU opened public consultations regarding investment protection under

the TTIP.8

Aiming to clarify most of these questions, the EU has taken significant

initiatives to establish a general framework regarding its involvement in ISDS.

In August 2014, after two years of negotiations, the Council and the

Parliament adopted Regulation 912/2014 (Financial Responsibility

Regulation/ FRR), which represents a milestone towards demarcating the

roles to be assigned to the EU and its Member States in ISDS under future EU

IIAs.9 More specifically, the Financial Responsibility Regulation establishes

rules concerning the apportionment of financial responsibility between the

EU and its Member States. It provides specific criteria for allocating financial

responsibility between the EU and its Member States, and it identifies in

which cases the EU and/ or its Member States can act as respondents in ISDS,

settle disputes, and be liable to pay damages to investors.

However, the Financial Responsibility Regulation is neither sufficient nor

always appropriate to guarantee legal certainty as to the involvement of the EU

in ISDS. First of all, the involvement of the EU and its Member States in ISDS

in accordance with the Financial Responsibility Regulation is not always in

line with international responsibility rules, while the inclusion of specific

provisions in EU IIAs is necessary in order to give effect to them. Moreover,

6. On the challenges regarding the content of EU IIAs beyond ISDS see European

Parliament Resolution of 6 April 2011 on the future European international investment policy

(2010/2203IINI); Reinisch, “The EU on the investment path – Quo Vadis Europe? The future of

EU BITs and other Investment Agreements”, 12 Santa Clara Journal of International Law

(2014), 111–157.

7. Commission Press Release, “EU and Canada strike trade deal” Brussels, 18 Oct. 2013,

available at <trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=973> ; Commission Press Release,

“Investment Provisions in the EU-Canada Free Trade Agreement”, 3 Dec. 2013, available at

<trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2013/november/tradoc_151918.pdf> .

8. Commission Press Release, “European Commission launches public online consultation

on investor protection in TTIP” 27 March 2014, available at <trade.ec.europa.

eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1052>.

9. Regulation 912/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a

framework for managing financial responsibility linked to investor-state dispute settlement

tribunals established by international agreements to which the European Union is party, O.J.

2014, L 257/121.

1674

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

it is unclear whether arbitration under the International Centre for Settlement

of Investment Disputes (ICSID) Convention10 may be included in EU IIAs as

an ISDS option. Secondly, the involvement of the EU in ISDS raises concerns

about compatibility with EU law rules. More specifically, the application of

the provisions of the Financial Responsibility Regulation can present a threat

to the autonomy of EU law, while the criteria under which financial

responsibility is allocated between the EU and its Members States differ from

internal EU law rules on EU and Member State liability. On top of that, the

application of the Regulation by the ECJ raises threats to the smooth

functioning of ISDS proceedings.

Thirdly, the Financial Responsibility Regulation does not deal with EU

involvement in ISDS under Member State BITs. Indeed, even if the EU is not

a party to a Member State BIT, disputes may arise when the EU is indirectly

involved, such as when the challenged measure relates to EU law. Such

situations may arise on the one hand under BITs that Member States have

concluded with third countries (extra-EU BITs). Although extra-EU BITs are

authorized according to Regulation 1219/2012,11 the FRR leaves important

questions concerning ISDS and the participation of the EU and its Member

States thereunder unanswered. On the other hand, such disputes may also arise

under BITs concluded between EU Member States (intra-EU BITs). The

involvement of the EU in ISDS under intra-EU BITs raises entirely different,

albeit related questions. Without entering into the details of the debate

regarding the compatibility of intra-EU BITs with EU law and whether they

should be terminated as a matter of principle,12 pragmatism requires

identification of how and in what circumstances the EU could and should be

involved in ISDS under intra-EU BITs.

Within this context, this article aims to provide a clear framework for the

participation of the EU and its Member States in ISDS. After explaining the

main characteristics of the Financial Responsibility Regulation, it examines if

and when EU involvement in ISDS under EU IIAs is compatible with

10. Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of

Other States (adopted 18 March 1965, entered into force 14 Oct. 1966), 575 UNTS, 159.

11. Regulation 1219/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December

2012 establishing transitional arrangements for bilateral investment agreements between

Member States and third countries, O.J. 2012, L 351/40.

12. Dimopoulos, “The validity and applicability of International Investment Agreements

between EU Member States under EU and international law”, 48 CML Rev. (2011), 63–93;

Hindelang, “Circumventing primacy of EU law and the CJEU’s judicial monopoly by resorting

to Dispute Resolution Mechanisms provided for in inter-se Treaties? The case of intra-EU

investment arbitration”, 39 LIEI (2012), 179–206; Von Papp, “Clash of ‘autonomous legal

orders’: Can EU Member State courts bridge the jurisdictional divide between investment

tribunals and the ECJ? A plea for direct referral from investment tribunals to the ECJ”, 50 CML

Rev. (2013), 1039–1081.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1675

international law. Afterwards, this contribution assesses the compatibility of

the Financial Responsibility Regulation with EU law and the constraints and

limitations that EU law imposes on EU involvement in ISDS under EU IIAs.

Finally, in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of EU involvement in

ISDS, this article offers a critical reflection of EU participation in ISDS under

Member State BITs.

2.

The Financial Responsibility Regulation

The Financial Responsibility Regulation aims to establish clear rules

concerning the apportionment of financial responsibility between the EU and

its Member States and explain how the EU and its Member States can be

involved in ISDS under EU IIAs. Limiting themselves to responsibility, EU

institutions avoided the temptation to resolve all matters pertaining to EU IIAs

in this Regulation. In that respect, it is noteworthy that the Regulation renders

clear that it is without prejudice to the delimitation of competences between

the EU and its Member States in the field of foreign investment. Despite the

Commission’s attempts to use this Regulation as a way to assert a broad FDI

competence under Article 207 TFEU,13 the Regulation makes clear that not

only is the Regulation without prejudice to the scope of the EU’s FDI

competence, but also that it does not constitute an exercise of the Union’s

shared competence regarding non-FDI aspects of foreign investment.14

Although competence questions are linked to international responsibility, as

explained below the Regulation cleverly avoids their determination.

In order to examine the implications of the Financial Responsibility

Regulation on how ISDS can function under EU IIAs, it is necessary to

understand first the objectives behind determining financial responsibility,

the scope of financial responsibility and its linkages to participation in ISDS,

the criteria under which responsibility is apportioned and the tools available

for ensuring compliance with it.

2.1.

The aims of the Regulation

The importance of creating a specific legal framework for EU and Member

State participation in ISDS under EU IIAs has been highlighted by EU

13. COM(2012)335 final, Proposal for a Regulation of the EP and of the Council

establishing a framework for managing financial responsibility linked to investor-state dispute

settlement tribunals established by international agreements to which the European Union is a

party, pp. 3–5.

14. Art. 1(1) FRR.

1676

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

institutions since the very first steps of EU investment policy. The

Commission indicated early on its aim to clarify the rules concerning

respondent status under ISDS and allocation of responsibility. In fact, the

Commission indirectly suggested that the EU will be internationally

responsible not only for EU acts, but also for any Member State acts affecting

foreign investments under future EU IIAs, thus covering violations of FDI and

non-FDI related provisions.15 Despite such initial proclamations, the fact that

participation in ISDS can have significant financial consequences for the EU

has made the Commission adopt a more nuanced approach towards

participation in ISDS and the apportionment of responsibility between the EU

and its Member States.

Indeed, unlike dispute settlement under the WTO, where the EU has been

willing to pay the costs for defending Member State measures and bear the

financial burden of any adverse rulings,16 the assumption of international

responsibility for all Member State acts violating investment obligations

raises very significant moral hazard concerns. Member States may act in

violation of their obligations under EU IIAs, knowing that compensation will

be paid by the EU and (indirectly) shared by all Member States. Of course, the

EU can bring infringement proceedings against Member States according to

Articles 258 and 260 TFEU and require that they comply with EU IIAs, which

are also binding on Member States as a matter of EU law.17 However,

infringement proceedings are unsuitable for apportioning responsibility

between the EU and its Member States. Infringement proceedings, where the

ECJ would in essence have to reassess whether a Member State complied with

the provisions of an EU IIA, would result in duplication of ISDS proceedings,

thus indirectly scrutinizing all arbitral awards and jeopardizing their

enforcement. More importantly, the remedies offered under Article 260 TFEU

are unsuitable for reimbursing the Union for any financial loss it may incur

under ISDS. Fines are neither appropriate nor sufficient to cover the damages

that the EU may have to pay in cases of severe violations of investors’ rights,

which may amount to billions of euros.

Within this framework, the EU is not eager to assume responsibility for all

violations of EU IIAs, since “[i]t would as a consequence be inequitable if

awards and the costs of arbitration were to be paid from the budget of the

15. Investment Policy Communication, cited supra note 2, p.10.

16. Cf. EC-LAN (WTO Panel Report of 22 June 1998, WT/DS62/R, WT/DS67/R,

WT/DS68/R); EC-Asbestos (WTO Appellate Body Report of 12 March 2001,

WT/DS135/AB/R); EC-Biotech (WTO Panel Report of 29 Sept. 2006, WT/DS291, 292,

293/R). See also infra section 3.3.1.

17. Case 104/81, Hauptzollamt Mainz v. Kupferberg [1982] ECR 3641, paras. 12–13; Case

C-13/00, Commission v. Ireland, [2002] ECR I-2943, para 15.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1677

European Union where the treatment was afforded by a Member State …”.18

The conclusion of EU IIAs should be budget neutral for the Union in

circumstances where Member States violate investors’ rights thereunder, so

the Regulation intends to guarantee “that the budget of the Union and Union

non-financial resources would not be burdened”.19 In that respect, this

Regulation deals with financial responsibility, namely with the question of

who bears the “obligation to pay a sum of money awarded by an arbitration

tribunal or agreed as part of a settlement and including the costs arising from

the arbitration”.20

2.2.

The scope of the Regulation: Linkages between financial and

international responsibility

The determination of financial responsibility is a question of EU law rather

than international law. The Financial Responsibility Regulation renders clear

that questions of financial responsibility are to be determined under this

Regulation in a manner that is independent from the determination of

international responsibility under ISDS.21 Despite proposals to link financial

responsibility with ISDS and render this Regulation part of EU IIAs22 – which

would be problematic as it would render Union law part of an international

agreement and thus threaten the autonomy of EU law23 – the Regulation aims

to determine financial responsibility as an internal EU law matter, decided

irrespective of international responsibility.

Nevertheless, the Regulation links financial responsibility with respondent

status in ISDS. More specifically, in cases where financial responsibility lies

with the Member States, the latter not only bear a Union law financial

obligation to pay costs, but more importantly, they become respondents in

ISDS and should bear an international law obligation to pay damages awarded

under ISDS. Article 9 FRR provides that, but for some limited exceptions,

when a Member States bears financial responsibility it is also respondent in

ISDS, while Article 18 FRR indirectly limits investors’ rights to pursue

18. Recital 5 FRR.

19. Recital 9 FRR.

20. Art. 2(g) FRR.

21. Recitals 3 and 5 FRR.

22. INTA, Draft Report on the proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of

the Council establishing a framework for managing financial responsibility linked to

investor-state dispute settlement tribunals established by international agreements to which the

European Union is party, PE504.106v01-00, 28.2.2013, Proposed amendment 50.

23. See infra section 4.1.1.

1678

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

payments for all awards rendered under EU IIAs from the EU.24 Moreover,

Member States have the right to settle disputes with investors, even when the

Union is respondent.25 As a result, financial responsibility is directly linked to

international responsibility, in that Member States participate in arbitration

proceedings, settle a dispute and are required to pay damages in cases where

they hold financial responsibility.

Article 9 FRR establishes three exceptions to the linkages between

financial and international responsibility.26 On the one hand, Article 9(2)(a)

FRR provides an exception in cases where financial responsibility is shared by

the Union and its Member States. In cases where the Union may, even partly,

bear financial responsibility, it is entitled to act as respondent, although

Member States would also bear financial responsibility. Article 9(3) FRR

offers a second exception in cases where similar claims are also raised in

WTO Dispute Settlement. Last but not least, Article 9(1)(b) FRR enables

Member States to decline to act as respondents, even though financial

responsibility lies with them. This provision establishes the main exception to

the linkage between financial responsibility and international responsibility,

as participation in ISDS is entirely independent from financial responsibility.

Yet, the Regulation provides, albeit only in hortatory language, that

international responsibility under EU IIAs should follow the division of

competences, so that only the EU could be held internationally responsible for

violations of provisions falling under exclusive competence.27 This statement

does not match with the implications that apportionment of financial

responsibility has on international responsibility and participation in ISDS. As

explained below,28 this statement contravenes one of the main objectives of the

Regulation, which is to guarantee that third country investors are not

disadvantaged by the fact that the EU and its Member States may both be

responsible under EU IIAs.29

24. The Commission will not pay for any awards where Member States have accepted

financial responsibility under Art.12 FRR or where a Member State has settled a case under

Art. 15 FRR.

25. Arts. 14(3) and 15 FRR.

26. The original Proposal submitted by the Commission provided two additional

exceptions. These would enable the Union to act as a respondent where the challenge concerned

treatment afforded by Member States, when similar claims were raised against a number of

Member States or if unsettled issues of law arose, (Commission Communication, cited supra

note 13, Art. 8(2)(c)-(d)). However, considering that in such cases only Member States would

incur financial responsibility, these provisions met strong resistance in the Council and were

later dropped, thus enhancing the principle that international responsibility reflects, to a large

extent, financial responsibility.

27. Recital 3 FRR.

28. See infra section 3.3.1.

29. Commission Communication, cited supra note 13, p.2.

Investor-state dispute settlement

2.3.

1679

The content of the Regulation: Allocation of financial responsibility

So far it has become evident that the determination of financial responsibility

is crucial for identifying in most cases whether the EU or its Member States

participate in ISDS under EU IIAs. In this respect, it is important to examine

the criteria according to which financial responsibility is apportioned between

the EU and its Member States. The key criterion for apportioning financial

responsibility is that such responsibility should be allocated to the entity that

afforded the treatment challenged as inconsistent with the relevant provisions

of an EU IIA.30 This principle is embodied in Article 3(1)(a) and 3(1)(b) FRR,

which provide that the EU and its Member States shall each bear the financial

responsibility arising from treatment afforded by them.

The determination of financial responsibility on the basis of the actor who

authored the challenged conduct is based on the principles of equity and

budget neutrality.31 Considering the high amounts of compensation that can

be awarded by investment tribunals, as well as the costs of investment

arbitration, the EU is willing to undertake only the costs related to its own

action. The nature of the remedies under ISDS, which involve significantly

high financial burdens, as well as the fact that the EU cannot always control

the conduct of Member States that results in violations of EU IIAs, would

render inequitable the allocation of financial responsibility to the EU for

Member State conduct.

Equity however requires a more nuanced approach in cases where Member

State conduct has been adopted within the framework of Union law. A strict

approach to allocation of financial responsibility on the basis of the author of

the challenged conduct would result in Member States bearing financial

responsibility for measures that they adopted in order to comply with EU law.

In that respect, Article 3(1)(c) FRR provides an exception concerning Member

State conduct that is “required by EU law”, while Article 2(l) defines such

conduct as “treatment where the Member State concerned could only have

avoided the alleged violation of the agreement by disregarding an obligation

under the law of the Union such as where it has no discretion or margin of

appreciation as to the result to be achieved”. Despite its complicated

wording,32 Article 3(1)(c) FRR provides in essence that in cases where the

challenged Member State measure is “required” by EU law, the EU bears

financial responsibility as long as prior Member State law was compatible

30. Recital 7 FRR.

31. Recitals 5 and 9 FRR.

32. Art. 3(1)(c) FRR is worded as an exception to 3(1)(b) FRR, while the second

subparagraph of 3(1)(c) FRR presents an exception to the exception, unless a specific condition

is met.

1680

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

with EU law, while the Member State bears financial responsibility if its prior

law was incompatible with EU law. However, the standards of apportionment

under this provision can be particularly problematic, especially if compared to

EU law rules on allocation of liability.

The allocation of financial responsibility is to be decided by the

Commission, after consulting with the Member States. Article 9(2) and (3)

FRR provide that in all cases where the Union acts as a respondent in ISDS

defending Member State conduct, a decision must be taken after following the

advisory or examination comitology procedures established in Articles 4 and

5 of Regulation (EU)182/2011.33 In cases where there is disagreement as to

the allocation of responsibility, Article 19 FRR provides a procedure for an ex

post facto determination of financial responsibility, after an award has been

rendered by an arbitral tribunal. The Commission has an obligation to offer a

detailed explanation of its position regarding the allocation of responsibility

and the Member States must respect tight timeframes in raising objections to

the Commission’s decision.

Compliance with the provisions determining financial responsibility may

be challenged before the ECJ. Such involvement of the ECJ in the application

and interpretation of the provisions of the Financial Responsibility Regulation

might, as explained below, pose threats to the smooth functioning of ISDS

proceedings.34

2.4.

Balancing the interests of the EU and its Member States: The role of

the duty to cooperate

In order to safeguard the allocation of financial responsibility between the EU

and its Member States and the determination of respondent status in ISDS and

settlement, the Financial Responsibility Regulation includes a system of

check and balances. It requires that the Commission and its Member States

consult each other and cooperate tightly, not only in cases where they share

responsibility,35 but even in cases where responsibility clearly lies with one of

them.36 In that respect, the Financial Responsibility Regulation is a

remarkable piece of legislation employing skilfully a vast array of obligations

enshrined in the duty of cooperation. Yet, its application can have undesirable

side-effects.

33. Regulation 182/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down the

rules and general principles concerning mechanisms for control by Member States of the

Commission’s exercise of implementing powers, O.J. 2011, L 55/13. See infra section 2.4.

34. See infra section 4.3.

35. Arts. 6, 9(3)-(5), 11, 13, 14 FRR.

36. Arts. 7, 8, 10, 15 FRR.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1681

More specifically, the most significant tool used in the Regulation which

guarantees cooperation between the Commission and the Member States is

the comitology procedure. In order to adopt decisions under Articles 9(3),

13(1), 14(8) and 16(3) FRR, where the examination procedure applies, the

Commission must in essence always have the consent of Member States,37

while decisions under Articles 9(2) and 15(3) FRR are to be taken only after

the Commission takes “utmost account” of the position of the Member

States.38 Besides, the Commission has a duty to render its decisions well

reasoned, “based on a full, balanced, factual analysis and legal reasoning

provided to the Member States”.39

In addition to comitology, the Financial Responsibility Regulation provides

a number of procedural safeguards, which guarantee that the Commission and

the Member States are duly informed and cooperate closely on any relevant

matters arising under ISDS. The Member States and the Commission are

obliged to duly notify each other of initiation of ISDS proceedings and any

steps they take thereunder,40 to share all relevant documentation and

information,41 and more importantly to consult with each other.42 Last but not

least, the Regulation also imposes substantive obligations on Member States

and the Commission in order to guarantee cooperation between them. Article

6(1) FRR provides that “… the Commission and the Member State concerned

will take all necessary steps to defend and protect the interests of the Union

and of the Member State concerned”. A number of other provisions emphasize

the obligation of the Commission to take into appropriate consideration the

Member States’ interests,43 focusing in particular on financial interests.44

The identification of specific procedural and substantive obligations born

by the Commission and the Member States is undoubtedly welcome. It renders

concrete which obligations arise out of Article 4(3) TEU in the context of

ISDS under EU IIAs. However, the enumeration of specific duties and

obligations potentially poses obstacles to the smooth operation of ISDS. This

is particularly so, since the Regulation does not identify the consequences of

the violation of these obligations and their impact on ISDS.

37. On the characteristics of these comitology procedures see Craig, EU Administrative

Law, 2nd ed. (OUP, 2012), pp.131–132.

38. Ibid.

39. Art. 9(2) FRR.

40. Arts. 6(2), 7(1), 8(1), 10(1)(b), 11(1)(d), 11(2), 15(3) FRR.

41. Arts. 6(2), 7(3), 10(2), 11(1)(c) FRR.

42. Arts. 6(2), 9(1) &(5), 10(1)(b), 11(1)(c), 14(1)-(4), 15(2), 16(1), 19(2) FRR.

43. Arts. 9(6), 10(1)(b), 11(1)(a), 13(1) FRR.

44. Arts. 9(4), 14(1),(4),(6), 16(1) FRR.

1682

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

Of course, any violation of the procedural conditions set for the adoption of

a Commission decision, such as the comitology rules, would be a ground for

challenging their validity under Article 263 TFEU.45 However, it is unclear

what are the ramifications in case of violations of general obligations to

cooperate, such as the obligation to cooperate under Article 6(1) FRR. Unlike

other areas of EU external relations, where a violation of the duty of

cooperation restricts the exercise of Member States’ external competences,46

any violation of the duty of cooperation under the Regulation should not affect

the external determination of respondent status, as this could seriously affect

the conduct of ISDS.47 Moreover, compliance with the duty to cooperate is not

a factor taken into consideration in the determination of financial

responsibility. Article 19(1) FRR provides that the allocation of financial

responsibility depends only on the basis of the criteria identified in Article 3

FRR, thus excluding the possibility of any other factor influencing how

financial responsibility is allocated in cases where one party does not

cooperate. This limitation on the ex post facto allocation of financial

responsibility may severely undermine the value of the duty to cooperate, as

its violation by Member States and the Commission would not bear any

financial consequences.

3.

EU involvement in ISDS under EU IIAs: International law

constraints

The Financial Responsibility Regulation, as a creature of EU law, is not

sufficient on its own to guarantee legal certainty regarding the involvement of

the EU in ISDS. On the contrary, the involvement of the EU in ISDS according

to the Financial Responsibility Regulation raises international law concerns.

This is particularly so, since not all international law rules are designed in a

way that can fully accommodate Regional Economic Integration

Organizations (REIOs), such as the EU.

More specifically, constraints arise firstly from international responsibility

rules. The determination of whether the EU and/or its Member States can be

respondent in ISDS under EU IIAs depends on whether they bear international

responsibility. However, the nature of the EU as a REIO, and the likely

conclusion of EU IIAs together by the EU and its Member States as mixed

agreements renders the determination of international responsibility difficult:

45. See infra section 4.3.1.

46. Case C-25/94, Commission v. Council (FAO Fisheries), [1996] ECR I-1469; Case

C-246/07, Commission v. Sweden (PFOS), [2010] ECR I-3317.

47. See infra section 4.3.2.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1683

on the one hand, international law has not yet developed crystallized rules

demarcating the international responsibility of the EU for acts of its Member

States and vice versa; and on the other hand, the EU treaty-making practice of

concluding treaties as mixed agreements renders the application of

international responsibility rules complex.

Secondly, constraints arise from the fact that the EU is an international

organization and not all types of ISDS are available to international

organizations. In that respect, it is unclear whether ICSID arbitration presents

a possible and fully functional ISDS option under EU IIAs, and if the

provisions of the Financial Responsibility Regulation facilitate the adoption

of ICSID arbitration.

3.1.

The involvement of the EU and its Member State in ISDS under

international law: The role of international responsibility

The involvement of the EU in ISDS is primarily a question of international

law. Arbitral tribunals must be satisfied that the respondent party to arbitration

meets certain conditions in order to have jurisdiction over a dispute and be able

to award damages. More specifically, the jurisdiction of arbitral tribunals

depends on whether the respondent party has given its consent to arbitrate a

case; the inclusion of an ISDS clause in an IIA is the most common way for

expressing a State party’s consent to ISDS.48 Moreover, arbitral tribunals must

be satisfied that the respondent party bears international responsibility, in

order to consider a claim admissible and award damages.49 Unless the

respondent can be held internationally responsible for a violation of an IIA

provision, an investor cannot claim damages for the loss suffered.

However it is questionable whether the determination of the respondent

party under EU IIAs in accordance with the provisions of the Financial

Responsibility Regulation satisfies these conditions. First, the identification

of the EU’s and its Member States’ international responsibility under EU IIAs

depends primarily on the apportionment of obligations between the EU and its

Member States under EU IIAs. For international responsibility to arise, a State

or an international organization has to be bound by a specific international law

obligation.50 Hence, only the party bound by an EU IIA provision can be held

responsible for its violation. Secondly the determination of whether the EU

and/or a Member State bear international responsibility depends on the

48. Of course, consent to arbitrate may be expressed ad hoc or through national law. See

Mihaly International Corporation v. Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (ICSID Case

No. ARB/00/2) 2002 at para 55.

49. See Paparinskis, “Investment treaty arbitration and the (new) law of State

responsibility”, 24 EJIL (2013), 617–647, at 627–629.

50. Art. 2.b of the ILC DARS and Art. 4b DARIO.

1684

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

attribution of the conduct violating the provisions of an EU IIA. International

law does not offer clear rules determining attribution of conduct to

international organizations and/or its members.51 Although the International

Law Commission (ILC) has worked towards clarifying this area of

international law, especially by endorsing the Draft Articles on the

International Responsibility of International Organizations (hereinafter

DARIO),52 it is uncertain how these rules apply for determining the

international responsibility of REIOs, such as the EU, and its Member States.

Given that the EU differs substantially from other international organizations

in that the implementation of EU obligations rests on both the EU and its

Member States,53 there are different approaches as to when conduct should be

attributable to the EU and/or its Member States.54

3.2.

ISDS under “pure” EU IIAs

First of all, participation in ISDS is problematic if EU IIAs are concluded only

by the EU, as “pure” EU agreements. In such cases, the framework established

under the Financial Responsibility Regulation cannot function properly,

creating uncertainty under international law as to who can act as respondent.

3.2.1. The constraints under international responsibility rules

If the EU is the only contracting party to an EU IIA, Member States cannot,

according to existing international responsibility rules, bear responsibility for

the violation of treaty obligations that they have not undertaken.55 In such

cases where the EU is the only subject assuming international obligations, it

appears at first glance that only the EU would bear international responsibility

51. On the different sources of international law concerning attribution of international

responsibility to international organizations see Tomuschat, “Attribution of international

responsibility: Direction and control” in Evans and Koutrakos (Eds.), The International

Responsibility of the European Union (Hart, 2013), pp.7–34.

52. Text adopted by the International Law Commission at its sixty-third session, in 2011,

and submitted to the General Assembly as a part of the Commission’s report covering the work

of that session (A/66/10). DARIO has been based on the ILC Draft Articles on State

Responsibility (DARS) (Text adopted by the International Law Commission at its fifty-third

session, in 2001, and submitted to the General Assembly as a part of the Commission’s report

covering the work of that session (A/56/10).

53. Member States are bound to comply with international treaties concluded by the EU.

Case C-13/00, Commission v. Ireland [2002] ECR I-2943, paras. 15, 21; Case C-459/03,

Commission v. Ireland (Sellafield), [2006] ECR I-4635, paras. 80–85.

54. See Kuijper and Paasivirta, “EU international responsibility and its attribution: From

the inside looking out” in Evans and Koutrakos (Eds.), op. cit. supra note 51, pp. 35–71, at

48–67.

55. Rosas, “International responsibility of the EU and the European Court of Justice” in

Evans and Koutrakos op. cit. supra note 51, pp.139–159, at 151.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1685

for any violation of the provisions of an EU IIA, and of course only the EU

could be party to ISDS.

However, excluding Member States from ISDS and international

responsibility would appear problematic, especially in cases where the

conduct resulting in the violation of the EU IIA is the act of an organ of a

Member State. This is evident in cases of expropriations resulting from

Member State measures. Even if EU law dictates the conditions under which

nationalization occurs,56 a measure amounting to expropriation can be

adopted by a Member State without having any link to EU law whatsoever. In

such cases, it is questionable whether the EU bears responsibility for acts of

Member States which it cannot prevent. On the one hand, it is debatable

whether international responsibility rules allow holding the EU responsible

for violations of EU IIAs resulting from Member States’ measures. The rules

contained in DARIO concerning attribution of conduct to international

organizations, such as Articles 7, 9 and 17 are not sufficient to attribute

Member State conduct to the EU, especially in circumstances where a Member

State measure is not directly related to EU law, such as an act of

expropriation.57 It has been advocated that Article 64 DARIO, which provides

that special rules relating to international responsibility may supplement more

general rules or even replace them, may be able to capture the nature of the

“normative” control that the EU exercises over its Member States in areas of

EU competence.58 Yet, as Article 64 DARIO does not clarify the extent to

which this rule applies to the EU, whether it covers all types of Member States’

acts and if it supplements or replaces the general rules on attribution, it is

contentious whether the EU could be held responsible for all Member State

measures that amount to violations of EU IIAs.

At the same time, it is questionable whether Member States can be held

responsible for their conduct. The assumption of an international obligation is

a conditio sine qua non for State responsibility to arise. Although it may be

possible to attribute the conduct of EU organs to Member States under

exceptional circumstances, such as under Article 61 DARIO,59 there is no

provision enabling Member State international responsibility where only the

56. Dimopoulos, EU Foreign Investment Law (OUP, 2011), pp.108–116.

57. Ibid., pp. 260–264.

58. Commentary on the ILC Draft Articles, Official Records of the General Assembly, 61st

Session, Supplement No.10 (A/64/10) (2009); Hoffmeister, “Litigating against the European

Union and Its Member States – Who responds under the ILC’s Draft Articles on International

Responsibility of International Organizations?”, 21 EJIL (2010), 723–747, at 726–727,

740-741. On the concept of normative control as a criterion for determining EU international

responsibility see Delgado, The International Responsibility of the European Union: From

Competence to Normative Control, (PhD thesis, EUI 2011).

59. Kuijper, “International responsibility for EU mixed agreements” in Hillion and

Koutrakos (Eds.), Mixed Agreements Revisited (Hart, 2010), pp. 219–221.

1686

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

EU has assumed a specific treaty obligation. As there is not yet any

international practice regarding Member State international responsibility for

their conduct violating the provisions of a “pure” EU agreement, it is still

unclear if Member States bear any responsibility at all.60

The uncertainty pertaining to the determination of international

responsibility for Member State conduct under “pure” EU IIAs has to be

avoided at all costs. ISDS is one of the most successful systems of

international dispute settlement, and there is no doubt that investors will use it

under EU IIAs. Any uncertainty regarding international responsibility would

undermine the level of protection offered, which presents the rationale behind

the inclusion of ISDS in EU IIAs in the first place. The lack of clarity not only

as to who bears responsibility, but if any party at all is internationally

responsible, could devastate the guarantees that ISDS aims to provide to

foreign investors. Moreover, the existence of uncertainties would create

internal, financial concerns in the EU as to who, the EU or a Member State,

should bear the costs of an infringement. Last but not least, it is questionable

whether arbitral tribunals are best situated to determine how the rules of

international responsibility apply to the EU and its Member States, a question

that neither the ECJ nor the ILC have managed to address yet in a conclusive

manner.

3.2.2. The deficiencies of the Financial Responsibility Regulation

Besides international responsibility concerns, the participation of Member

States in ISDS under “pure” EU IIAs would cast doubt on the jurisdiction of

arbitral tribunals. Given that Member States did not sign “pure” EU IIAs, they

have not expressed therein their consent to be parties to arbitration, so arbitral

tribunals may lack jurisdiction to hear claims brought against Member States.

Of course, this obstacle could be overcome if Member States offer their

consent ad hoc in cases where they bear financial responsibility. However, this

would not be satisfactory, as Member States are not under any obligation

under international or Union law to consent to ISDS. Since the Financial

Responsibility Regulation does not impose such an EU law obligation on

Member States to consent to arbitration either, there is no legal obligation or

incentive for Member States to consent to ISDS under “pure” EU IIAs.

In that respect, participation in ISDS under “pure” EU IIAs should be based

on an entirely different framework. On the one hand, the inclusion of ISDS in

“pure” EU IIAs has to be accompanied by specific rules on the allocation of

international responsibility between the EU and its Member States. Legal

certainty requires ISDS clauses to be accompanied by an explicit assumption

of EU international responsibility for all violations of its provisions, including

60. Rosas, op. cit. supra note 55.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1687

those resulting from Member State conduct. Such specific recognition of

single EU international responsibility would safeguard the autonomy of EU

law, guarantee the rights of investors under ISDS and comply with

international responsibility rules.

On the other hand, the provisions of the FRR on Member State participation

in ISDS, such as Articles 9, 10, 14(3), 15 and 18 FRR would be incompatible

with the provisions of the EU IIA. Given the priority that EU law offers to EU

international agreements over secondary law,61 these provisions would be

inapplicable. In such cases, the rules pertaining to the EU acting as respondent

in cases where the Member State is financially responsible would be of utmost

importance. Similar to Article 9(1)(b) FRR, the obligations of the Union to act

in the best interest of the Member State and to cooperate fully with the

Member State involved62 will be particularly important for all cases where

Member State conduct is challenged. At the same time, the rules concerning

financial allocation of responsibility and Member State obligations to pay into

the Union budget, in particular Articles 19 and 20 FRR, would be pertinent. In

order to guarantee the principles of equity and budget neutrality that the

Financial Responsibility Regulation adheres to, allocation of financial

responsibility would become very pertinent if the EU bore international

responsibility for all violations of EU IIAs provisions.

3.3.

ISDS in EU IIAs concluded as mixed agreements

Despite the possibility of concluding EU IIAs as “pure” EU agreements, EU

negotiating practice indicates that ISDS will be included in most cases in

comprehensive trade, investment and cooperation agreements that will be

concluded by the EU and its Member States jointly as mixed agreements.

Indeed, Member States are expected to conclude CETA and TTIP agreements

together with the EU.63 Yet, the conclusion of EU IIAs as mixed agreements

does not render the determination of the role of the EU under ISDS much

easier. On the contrary, unless ISDS provisions are carefully drafted, the

determination of respondent status in accordance with the provisions of the

Financial Responsibility Regulation can significantly affect legal certainty.

61. Case C-366/10, Air Transport Association of America v. Secretary of State for Energy

and Climate Change, [2011] ECR I-1133, paras. 49–51; Case C-311/04, Algemene Scheeps

Agentuur Dordrecht, [2006] ECR I-609, para 25.

62. Arts. 9(6) and 11 FRR. See supra section 2.4.

63. See supra note 7. Commission Press Release, “Speech: The Transatlantic Trade and

Investment Partnership: The Real Debate”, 22/5/2014, available at <europa.eu/rapid/

press-release_SPEECH-14-406_en.htm>.

1688

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

3.3.1. The role of EU exclusive competence

The determination of respondent status in ISDS under EU IIAs concluded as

mixed agreements is mainly problematic due to the exclusive nature of EU

competence in the field of FDI. This is so, because in areas of a priori

exclusive competence, such as FDI, only the EU assumes international

obligations towards third countries. Hence, as with the above-discussed

“pure” EU IIAs, questions arise regarding international responsibility for

Member State conduct violating obligations that fall under EU exclusive

competence.

More specifically, international law requires that both the EU and its

Member States assume full rights and obligations over the whole breadth of a

mixed agreement that they conclude jointly.64 The only exception to this rule

is the existence of a manifest violation of the internal EU rules demarcating

competence. Articles 27 and 46 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of

Treaties between States and International Organizations and between

International Organizations of 198665 recognize that the division of

competence is primarily an internal question that does not affect the validity of

the obligations entered into by the EU and its Member States. However, if

there is a clear lack of competence to assume an obligation, and this is

objectively evident in accordance with normal State practice and good faith,

such as in cases of a priori exclusive competence, then limited responsibility

exists along the lines of the division of competences.66 Without entering into

details, suffice it to note that the EU in its treaty-making practice, as well as the

ECJ, have long relied on the division of competences between the EU and its

Member States as a criterion for demarcating the EU’s and Member States’

obligations under mixed agreements.67 In that respect, the existence of EU

exclusive competence over FDI indicates that only the EU has assumed

obligations related to FDI. Hence, similar to “pure” EU IIAs, it is unclear

when and who bears responsibility for violations of FDI-related provisions

resulting from Member State measures, especially when the latter are not

related to EU law.

64. Bleckmann, “The mixed agreements of the EEC in public international law” in

O’Keeffe and Schermers (Eds.) Mixed Agreements (Kluwer, 1983), p.159.

65. 1155 UNTS 331. Even though the Vienna Convention has never come into force, it is

generally recognized as codifying principles of customary international law. Steinberger, “The

WTO treaty as a mixed agreement: Problems with the EC’s and the EC Member States’

membership of the WTO”, 17 EJIL (2006), 837–862, 843.

66. Ibid, 844–845.

67. Opinion of A.G. Mischo in Case C-13/00, Commission v. Ireland, [2002] ECR I-2943,

paras. 29, 30; Kuijper and Paasivirta, “Further exploring international responsibility: The

European Community and the ILC’s project on responsibility of international organizations”,

1 International Organizations Law Review (2004), 111–138, at 119; Hoffmeister, op. cit supra

note 58, at 743.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1689

Current developments regarding EU and Member State responsibility

under the WTO are illustrative of the lack of clear rules regarding international

responsibility for Member State acts violating a provision falling in an area of

EU exclusive competence. In the field of trade in goods, where the EU has

exclusive competence, the EU has always been eager to assume responsibility

for all violations of GATT provisions. Besides, WTO panels and the Appellate

Body have always been eager to accept the EU’s assumption of responsibility

for Member State measures.68 Yet, in all these cases, the EU was held

internationally responsible when Member States were acting within the

framework of EU law. On the contrary, in the Airbus case, which concerned

the compatibility of both EU and Member State measures with WTO law, the

Panel departed from prior case law and ruled that the Member States, being

members of the WTO, were responsible for the actions of their organs.69

Without explaining why it did not accept the EU’s readiness to assume

responsibility for Member State actions, the Panel seems to have accepted

Member State responsibility for their actions, since the latter were adopted

and implemented outside the EU legal framework, and thus, Member States

were better suited to remedy this violation.70 Yet, the Panel did not contest the

EU acting as the only respondent in dispute settlement proceedings, nor the

EU’s readiness to bear the full costs.

The lack of clarity regarding Member State international responsibility for

their conduct resulting in violation of FDI provisions has significant

repercussions for ISDS. In addition to the problems identified above with

regard to “pure” EU IIAs, if EU IIAs are concluded as mixed agreements, the

degree of uncertainty becomes greater, given that it is not yet clear which

aspects of EU IIAs fall under the EU’s exclusive FDI competence. More

importantly, the possibility of investment tribunals deciding on the existence

of international responsibility based on the existence of exclusive competence

would present a major threat to the autonomy of EU law. As explained below,

preserving the autonomy of EU law means that investment tribunals should

not be entitled under EU IIAs to decide, even indirectly, on the allocation of

competences between the EU and its Member States.71

3.3.2. Shared competence and the problem of attribution of conduct

Even in areas of shared competence, which cover all non-FDI provisions of

EU IIAs, the determination of respondent status is complicated. On the one

hand, the apportionment of obligations is not self-evident. The ECJ seems to

68.

69.

70.

71.

Supra note 16.

EC-Airbus, WTO Panel Report 30 June 2010, WT/DS316/R.

Kuijper and Paasivirta, op. cit. supra note 54, p. 63.

See infra section 4.1.3.

1690

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

favour a competence-based allocation of international obligations, according

to which the assumption of obligations depends primarily on the

determination of the actor who exercised its (shared) competence at the time

of the conclusion of the EU IIA. Yet the Court offers little guidance as to how

this can be done. The Court has accepted that the EU may exercise its shared

competence,72 and it linked the actual exercise of shared competence with the

legal basis used for the adoption of the mixed agreement.73 Yet, it is difficult

to extract definitive answers, since legal basis is only one indication of the

exercise of shared competence, which rests on other factors as well. Moreover,

it is highly unlikely that the EU will use in its EU IIAs a declaration of

competences, a tool that has proven rather useless in the past,74 to demarcate

the exercise of its investment powers. In that respect, apportioning non-FDI

obligations of EU IIAs to both the EU and the Member States would seem

more probable under international responsibility rules.75

On the other hand, even if obligations under EU IIAs in areas of shared

competence are equally apportioned to the EU and its Member States, the

identification of international responsibility remains complicated, as it would

depend on the attribution of the conduct violating an EU IIA provision. As

discussed above, there have been many attribution criteria that have been

proposed as suitable to reflect the realities of EU and Member State action

under the framework of EU law, which can be based upon different DARIO

provisions.76 Depending on the criterion chosen, it is possible to hold the EU

responsible for any violation of EU IIA provisions, such as under the WTO

framework,77 all the way to holding Member States responsible for acts of EU

organs.78 Considering the divergent rules and current practice concerning

attribution of responsibility under mixed agreements, it becomes apparent

why the inclusion of ISDS provisions in EU IIAs should be accompanied by

the explicit identification of attribution criteria, in a way that safeguards legal

certainty and promotes the policy choices on internal allocation of

responsibility which the EU favours.

72. Case C-239/03, Commission v. France (Etang de Berre), [2004] ECR I-9325, para 30.

73. Commission v. Ireland (Sellafield), cited supra note 53, paras. 96–97.

74. For a critical analysis of the impact of declarations of competence on international

responsibility see Heliskoski, “EU declarations of competence and international

responsibility” in Evans and Koutrakos (Eds.), op. cit. supra note 51, pp.189–212.

75. Case C-316/91 European Parliament v. EDF [1994] ECR I-625, para 29; Eeckhout,

“The EU and its Member States in the WTO: Issues of Responsibility” in Bartels and Ortino

(Eds.), Regional Trade Agreements and the WTO System (OUP, 2006), p. 464; ILC

Commentary-2009, op. cit. supra note 58, p.144.

76. Kuijper and Paasivirta, op. cit. supra note 54; Delgado, op. cit. supra note 58.

77. Kuijper and Paasivirta, op. cit. supra note 54, pp. 60–63.

78. Ibid., pp. 65–67.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1691

Rendering financial responsibility possible: The need for joint and

several responsibility under EU IIAs

Unlike “pure” EU agreements, allocation of responsibility under the Financial

Responsibility Regulation can function appropriately if EU IIAs are

concluded as mixed agreements. The conclusion of EU IIAs as mixed

agreements could not only guarantee adherence to the principles of

apportionment of financial responsibility elaborated in the Regulation, but

also, as explained below, render possible the inclusion in EU IIAs of ICSID

arbitration as an available and fully functioning ISDS option. However, this

depends on how international responsibility under EU IIAs will be divided

between the EU and its Member States.

More specifically, the determination of respondent status under the

Financial Responsibility Regulation cannot be properly applied, if

international responsibility under EU IIAs is determined only on the basis of

competence. In such cases, only the EU would be able to act as respondent and

be responsible for all violations relating to FDI, irrespective of whether

financial responsibility for such violations would be apportioned to Member

States. Similar to “pure” EU IIAs, the provisions of the Financial

Responsibility Regulation concerning respondent status, conduct of

arbitration, settlement and payment would be inapplicable.79 The fact that

competence should not be used as the sole criterion for establishing

international responsibility under EU IIAs does not necessarily undermine its

value within EU law. The determination of international responsibility under

EU IIAs should be based on additional – to competence – criteria, which can

enhance legal certainty under international law and enable the system

established under the Financial Responsibility Regulation to work

successfully. Besides, since the exact determination of EU exclusive

competence remains a highly contentious matter, which more than 5 years

after the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty has not yet been clarified, any

competence-based allocation of responsibility should be avoided.

In that respect, EU IIAs should explicitly establish joint and several

responsibility for all violations of EU IIAs provisions. EU IIAs could

explicitly provide that the EU and its Member States jointly assume all

obligations provided thereunder and have joint and several responsibility for

any violation occurred. Adding to legal certainty, such an approach would

allow third-country investors to bring claims against both the EU and its

Member States, while arbitral tribunals would in all cases have jurisdiction

and be able to award damages, irrespective of whether the EU or a Member

State acts as respondent.

3.3.3.

79. Supra note 61.

1692

Dimopoulos

CML Rev. 2014

The joint assumption of all obligations would be particularly crucial for

enabling Member State international responsibility in areas of EU exclusive

competence. Only if Member States explicitly assume international

obligations that may fall under EU exclusive competence, can they be held

internationally responsible for their conduct and act as respondents in ISDS

according to the provisions of the Financial Responsibility Regulation. At the

same time, the explicit acknowledgment and adoption of Member States

conduct by the EU and vice versa, according to the principles provided in

Articles 9 and 61(1)(a) DARIO, would enable the EU to act as respondent and

assume responsibility for the conduct of Member States in all circumstances.

This would be particularly relevant for situations covered under Article

9(1)(b) FRR, where the Union acts as respondent in cases where the violation

results from Member State conduct that is not linked to EU law.

The explicit adoption of joint and several responsibility under EU IIAs is

nothing new under EU international agreements. The ECJ favours the

existence of joint and several responsibility under mixed agreements, as they

enable third countries to choose either to seek remedies from the EU and its

Member States together or the party of their choice for the whole of the

damages suffered.80 Moreover, international law favours the existence of joint

and several responsibility in cases where an obligation is violated that both the

EU and Member States bear equally, since responsibility cannot be

apportioned between them and each of them is fully liable to the injured

party.81 As regards the language that can be used in EU IIAs, various options

are available: EU IIAs could of course directly acknowledge joint and several

responsibility for any violations of their provisions. However, they may adopt

more indirect language, such as requiring arbitral tribunals to accept that

whether the EU or a Member State acts as respondent does not affect the

admissibility of a claim or the jurisdiction of a tribunal.

3.4.

ICSID arbitration as an ISDS option under EU IIAs

Despite the great diversity of fora provided in IIAs for settlement of

investment disputes, ICSID arbitration has been the main mechanism used

broadly since the emergence of ISDS. Unlike other ISDS options, which are

primarily used for private commercial arbitration, such as UNCITRAL

arbitration rules, ICSID offers a unique arbitration system that combines

elements of both commercial and inter-state arbitration. While it adheres to

the basic rule of arbitration that consent of the parties is a condition sine qua

non, it requires double consent of the defendant State party, one of them being

80. European Parliament v. EDF, cited supra note 75.

81. Art. 47 DARIO; ILC Commentary-2009, op. cit. supra note 58, p. 77,144.

Investor-state dispute settlement

1693

the ratification of the ICSID Convention, the other relating to the specific

dispute, which is usually expressed by conclusion of an IIA. More

importantly, it provides for annulment and legal review of awards as well as for

a strong and efficient enforcement mechanism of ICSID awards. ICSID

obliges States to treat them as if they were a final judgment of a national court,

thus avoiding the restrictions posed by the New York Convention on the

Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitration Awards.82

Considering the benefits that ICSID arbitration offers to investors in

comparison to other ISDS options, the EU is willing to include ICSID as an

available ISDS option under EU IIAs.83 The inclusion of ICSID arbitration as

an ISDS option could be particularly beneficial for EU investors, maximizing

the benefits that they can draw from the conclusion of EU IIAs.84 Yet, it is

questionable whether ICSID is a truly available ISDS option under EU IIAs,

especially given the determination of respondent status under the FRR.

3.4.1. Constraints under international law

International law places constraints on the inclusion of ICSID arbitration in

EU IIAs. As the ICSID Convention is open only to States,85 it is doubtful