Networks, Careers, and the Jihadi Radicalization of Muslim Clerics

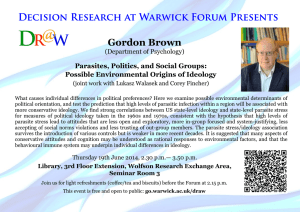

advertisement