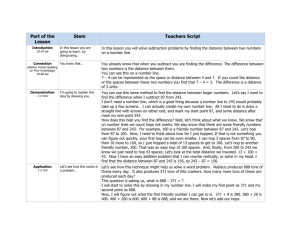

-t1 Ff1ice:ic icLr! Lrodu:iii, F1Iij 3rL

advertisement