Health Policy Salaries and incomes of health workers in sub-Saharan Africa

advertisement

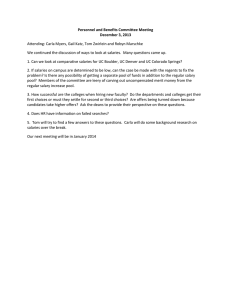

Health Policy Salaries and incomes of health workers in sub-Saharan Africa David McCoy, Sara Bennett, Sophie Witter, Bob Pond, Brook Baker, Jeff Gow, Sudeep Chand, Tim Ensor, Barbara McPake Public-sector health workers are vital to the functioning of health systems. We aimed to investigate pay structures for health workers in the public sector in sub-Saharan Africa; the adequacy of incomes for health workers; the management of public-sector pay; and the fiscal and macroeconomic factors that impinge on pay policy for the public sector. Because salary differentials affect staff migration and retention, we also discuss pay in the private sector. We surveyed historical trends in the pay of civil servants in Africa over the past 40 years. We used some empirical data, but found that accurate and complete data were scarce. The available data suggested that pay structures vary across countries, and are often structured in complex ways. Health workers also commonly use other sources of income to supplement their formal pay. The pay and income of health workers varies widely, whether between countries, by comparison with cost of living, or between the public and private sectors. To optimise the distribution and mix of health workers, policy interventions to address their pay and incomes are needed. Fiscal constraints to increased salaries might need to be overcome in many countries, and non-financial incentives improved. Introduction The pay and income of health workers affect health care and health systems in many ways. Pay and income have been described as hygiene factors1 that affect motivation, performance, morale, and the ability of employers to attract and retain staff. When pay is low in absolute terms, health workers will moonlight to supplement their incomes by providing health-care services privately, engaging in other income-earning activities, extracting informal fees from their patients, or seeking per-diem payments by attending workshops and seminars.2 The wider earning power of health workers depends on the context in which they work; richer urban settings generally provide opportunities for private practice, whereas rural regions provide opportunities to supplement pay with non-financial income such as locally grown food. Health workers are also affected by relative differences in pay and income. Relatively low pay can cause dissatisfaction and loss of motivation, and cause migration towards higher earning jobs. The size of the pay differential between different types of health worker (eg, doctors and nurses) can also affect morale, working relationships, and the available mix of cadres. Differences in pay and income can therefore affect both retention within countries and distribution of health workers, whether between urban and rural areas or between the public and private sector. Pay for health workers is also an important determinant of overall health expenditure. In 2006 in Ghana, for example, when health worker pay and emoluments went 35% over budget, they absorbed 76% of government spending on health; this left only 6% of the government budget for non-wage recurrent expenditure once capital expenditure had been spent.3 Availability of data Policy debate and discussion about health-worker salaries and incomes in countries with low and middle incomes is constrained by insufficient data. In theory, data on public-sector pay should be readily available from www.thelancet.com Vol 371 February 23, 2008 government databases, but in practice, such data are inaccurate, incomplete, unclear, and out of date.4–6 Pay structures are often complex, consisting of a mix of salary, various allowances, periodic bonuses, overtime payments, and other forms of remuneration such as per diems. Most data exclude non-wage benefits (such as employers’ contributions to pensions, medical insurance, and housing); unofficial payments or gifts from patients; and other income from private sources. Because data collection is not standardised or consistent, cross-country comparisons and analyses of longitudinal trends are difficult. Cross-country comparisons are also hindered by differences in job descriptions, roles, and levels of training. Another difficulty is that data about the average salary of a particular type of health worker might not reflect variations in pay for subsets of workers within that grade (eg, different types of nurses). Data on health workers who are employed in the private sector are more scarce than those for government staff, notwithstanding concerns about the brain drain of health workers from the public sector.7,8 The heterogeneity and lack of regulation that characterise this sector in sub-Saharan Africa complicate data collection. Even if the commercial private sector is excluded, scores of non-profit organisations employ health workers under different terms and conditions of service. Because of the poor quality of routinely collected data, we searched recent surveys of health-worker pay and income in sub-Saharan Africa. We searched Medline, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, International Labour Organization (ILO), and WHO websites. We also consulted expert researchers and WHO staff. We obtained public-sector data from two surveys by the Initiative for Maternal Mortality Programme Assessment (IMMPACT) in Burkina Faso9 and Ghana,10 and from two by the World Bank in Zambia11 and Nigeria,12 in collaboration with country governments (table 1). We have also drawn on three other sources of secondary data from Zambia,13 Ethiopia,14 and Malawi.15 Lancet 2008; 371: 675–81 See Editorial page 623 See Comment page 632 Centre for International Health and Development, University College London, UK (D McCoy DrPh, S Chand MFPH); Alliance for Health Systems and Policy Research, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland (S Bennett PhD); IMMPACT, University of Aberdeen, UK (S Witter MA, T Ensor PhD); World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland (B Pond MD); Health GAP, Northeastern University School of Law, Boston, MA, USA (Prof B Baker JD); Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, UK (B McPake PhD); and Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Division, University of Kwazulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa (J Gow PhD) Correspondence to: David McCoy, Centre for International Health and Development, University College London, 30 Guilford Street, London WC1N 1EH, UK d.mccoy@ucl.ac.uk 675 Health Policy Year of survey Burkina Faso Ghana Nigeria 2006 2005 2001 96 374 717 Number of respondents Sampling Two rural districts (Diapaga and Ouargaye) 12 rural and urban districts in two regions (Central and Volta) Zambia 2005 Not stated, but at least 242 252 public primary-care facilities in two states (Lagos and Kogi, which are urban and rural, respectively) 171 public facilities including hospitals and primary care in two urban and three rural provinces Data are from references 9, 10, 11, and 12. Table 1: Sources of survey data Agricultural Commerce and Clinical work petty trade work Other activities Medical officers 0 30·0% 10·0% 0 0 Community health officers 8·4% 12·6% 2·5% 6·7% 5·0% 1·7% 14·3% 17·9% 0 10·7% 3·6% 2·1% Nurses 0 Home health Sale of service medicines Data are from references 12. Table 2: Supplementation of public-sector pay in Nigeria by different types of health workers History of public-sector pay and income Trends in employment and remuneration of civil servants in sub-Saharan Africa reflect those for government health workers. In the decade before 1985, numbers of civil servants in many sub-Saharan African countries grew at more than 5% every year.16 In Ghana, for example, the civil service was five times as large in the 1980s as it had been at independence in 1957,17 and about 30% of all Ghanaian civil servants worked for the Ministry of Health. And yet, sub-Saharan Africa has consistently had fewer central government employees as a proportion of total population than other regions of the world (1·1% in the early 1990s compared with an average of 1·3% for developing countries in Asia and Latin America). At the same time, countries in sub-Saharan Africa have devoted a higher proportion of low GDP to pay these workers (6·7% of GDP in the early 1990s compared with 4·8% in developing countries in Asia and Latin America).4 High inflation and structural adjustment programmes reduced real wages in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, with the exception of those that were formerly under French rule. For example, in real terms, the average civil-service salary in Tanzania in 1985 was only a quarter of what it had been 10 years earlier.16 When both real and nominal civil-service wages decreased, the value of benefits such as housing and transportation assumed a more important role. In Senegal, non-wage benefits increased from 25% in 1980–85 to 43% in 1989 as a proportion of total compensation for civil servants.16 Another feature of this period was so-called wage compression, in which proportionately higher nominal wage increases were awarded to lower-level employees, thus reducing the ratio between the salaries of the most qualified and senior staff and the salaries of less qualified staff.18 In Zambia, the ratio between the salary of an undersecretary and that of the lowest-paid salaried 676 employee was 19 to one in 1970, and fell to seven to one in 1983.19 Progressively worse salary compression “eventually leads to loss of employees with options, i.e., the better employees” and “difficulty in recruiting qualified outsiders, and a ‘deskilled’ workforce too poorly paid to resist temptation.”4 In the late 1970s and early 1980s, government wage bills, and health wages in particular, contributed to large fiscal deficits. Such deficits became unsustainable for many countries and led to structural adjustment in the 1980s and 1990s, which aimed to get countries to pay their debts and balance their books. Reforms included freezes on hiring; cessation of pay increases linked to inflation; elimination of automatic promotions; voluntary and compulsory retirement; and removal of “ghost workers” from the payroll.18–23 Between 1986 and 1996, real wages for civil servants fell in 26 of the 32 sub-Saharan Africa countries for which data are available.16 Real wages fell most precipitously in the formerly French colonies after their currency was devalued by 50% in 1994. In Nigeria, from 1980 to 1993, the official monthly wage of senior civil servants in constant 1995 international dollars (adjusted for purchasing power) dropped from US$820 to US$234.24 Nine countries also lowered non-wage benefits, although five countries managed to raise them.16 At least 21 countries resorted to retrenchment of some civil servants.16 The number of civil servants decreased, especially in Uganda and francophone countries. In Uganda, the number of civil servants dropped from 320 000 in 1989 to around 148 000 by 1997.25 Of 22 countries for which data exist, the proportion of civil-service employees in the population decreased either “sizeably” or “moderately” in all but one country between 1986 and 1996.18 Civil-service reforms during this period of structural adjustment (1980–90s) typically failed to counter wage compression. The governments of Ghana, Mozambique, and Uganda were exceptions; they adopted specific measures to decompress wage structures as part of their civil-service reforms.4 For example, in Uganda, retrenchments combined with increased donor funding and some economic growth permitted civil-service wages to be decompressed and increased on average by more than nine-fold in real terms between 1990 and 1996. What has been the trend in government employment and wages over the past ten years? The IMF has tracked government expenditures on employment for the www.thelancet.com Vol 371 February 23, 2008 Health Policy Private income Per diems Share of user fees Allowances Salary 1200 800 Allowances Salary 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 600 0 Do ct or Ph ar bo m ra a c is to ry t sc ien tis t Tu t Se or ni or nu rse Nu rse M id La w C lin ife bo i ra to cal o ry ffi te ce ch r Ph no ar lo m gi ac st yt ec hn ic i an Monthly income (US$) 1000 1600 Monthly income (US$) 1400 400 La 200 0 Doctor Medical assistant Midwife Nurse Community nurse Figure 1: Monthly income for health workers in the public sector in Ghana in 2005 (US$) Data are from reference 10. 41 countries that they supported with Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility loans.26 Their data show that in 2005, the average government wage bill in sub-Saharan Africa was 6·6% of GDP, which is roughly the same as it was during the early 1990s. This was lower than in Central America (11%) but higher than Central Asia (3·7%) and Asia (4·6%). Structure and sources of pay Public-sector pay is commonly composed of different elements, with basic salary a small component of overall pay. The Ghana survey, for example, showed that in 2005, only 26% of a doctor’s monthly income was basic salary, compared with 43% of that of mid-level workers such as medical assistants (figure 1).8,10 Allowances (of which an allowance for additional hours of duty was the largest) contributed more to total income than did salary. The Zambia survey also showed the importance of allowances (figure 2), which constituted nearly 40% of doctors’ incomes from government.11 Therefore, allowances decompress the salary scale across the workforce. Compared with the salary of a community nurse, a doctor’s salary in Ghana was three times higher and their income was four times higher.10 Similarly, in Zambia, allowances meant that doctors were paid about four times more than nurses or midwives.11 The large difference in pay between doctors and other skilled clinical staff such as medical assistants, clinical officers, and senior nurses highlights the importance of pay to sector-wide HR planning and getting the right mix of types of health workers. The survey data from Burkina Faso neither disaggregated basic salary income from allowances, nor captured data for doctors (figure 3).7,9 However, it did reveal that per diems for attending workshops and training events accounted for about 10% of total income, and that user fees were another important source of supplementary income. www.thelancet.com Vol 371 February 23, 2008 Figure 2: Monthly income for health workers in Zambia in 2005 (US$) Data are from reference 11. The surveys reported that income from private practice made up only 0·1% of the earnings of health workers in the public sector in Ghana, and close to zero in Burkina Faso.9,10 However, these figures probably reflect under-reporting, since in Burkina Faso, only 32% of survey respondents said they would agree to a new contract to outlaw private practice; more said they would accept such a contract only if their public salary was doubled.9 In the Nigerian survey, 45% of staff reported that they supplemented their income privately (table 2).12 The Zambian survey also reported that many health workers had generated income by other activities; this was more common in urban than rural health centres (32% and 9% of staff, respectively).11 These surveys did not calculate the monetary value of benefits such as free housing or transport. The adequacy of pay Policy makers need to be able to judge the adequacy of pay to assess to what extent it contributes to the bad distribution, poor retention, and low motivation of public sector health workers. One way is to compare pay against a measure of the cost of living (table 3). However, since prices of goods and services vary over time, and in different parts of a country, and the basket of services and goods selected to estimate the cost of living might not always be easily comparable between countries, the cost of living is not easy to measure. The calculation of purchasing power parity is based on an exchange rate that equalises the value of comparable market baskets of goods and services between countries. Although purchasing power parity has limitations, it is seen as the best available method by which to compare incomes and prices between countries. Another approach is to benchmark the salaries of health workers against the average gross national income (GNI) per person. In Ghana, in 2005, nurses earned nearly 11 times as much as the GNI per person, whereas doctors earned about 32 times the GNI per person.10 By contrast, the average government salary was four times the GNI per 677 Health Policy 3000 estimated Ghanaian doctor’s salary of US$14 600, although the real disparity is smaller when cost of living is taken into account. Another way to judge the adequacy of pay for health workers in the public sector is to compare it to pay in the private sector. In Ethiopia, concern has arisen that government and university salaries did not match those in the donor and non-government sector. For example, a driver for a US bilateral agency in Addis Ababa was paid more than a professor in the medical faculty, and a government public-health specialist could earn four to five times more by joining an international non-governmental organisation (NGO) (table 4).14 In Zambia in 2004, private health facilities paid much higher salaries than did the government or NGOs.13 Private doctors’ salaries were more than double those of government doctors; midwives’ salaries were almost a third higher; and laboratory technicians’ salaries were more than three times those in government. NGOs paid between 23% and 46% more than the government. The study also showed that the private sector used incentive payments, which were as much as 52% of a year’s salary for one group of private-sector doctors (table 5).13 However, employment in the private sector does not automatically mean a higher total income. In fact respondents from the Burkina Faso survey mentioned that one of the reasons for remaining in the public sector was that it provided a good salary.9 The survey from Ghana also showed that midwives who worked in private clinics had lower incomes than their public-sector counterparts, although this could have been because the respondents were often retired individuals who did not work full time.10 In Malawi, a survey of NGOs in 200515 showed that the average salaries paid by international NGOs were higher than salaries paid by local NGOs (eg,US$43 162 per year and US$29 231 per year, respectively for nurses). Expatriate Income from gifts Income from per diems Income from user charges Salary and allowances Annual income (US$) 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Auxiliary midwife Outreach health worker Statecertified nurse Stateregistered nurse Village midwife Stateregistered male midwife Stateregistered female midwife Figure 3: Annual income for health workers in Burkina Faso in 2005 (US$) Data are from reference 9. person. In Zambia, doctors earned forty times the GNI per person.11 In both Zambia and Burkina Faso, registered midwives received more than six times the average GNI, whereas auxiliary midwives in Nigeria earned about eleven times the average GNI.9,12 This measure also allows some cross-country comparisons: the pay of a public-sector nurse varied from about five times the GNI per person in Burkina Faso to about 11 times in Ghana.9,10 Table 3 shows that if salaries were simply converted to US dollars with official exchange rates, doctors from Ghana would seem to earn less than doctors from Zambia. However, conversions according to purchasing power parity suggest that doctors in Ghana earn more than their counterparts in Zambia. Although doctors’ incomes were higher than those of other health workers and the rest of the population, they were low by international standards. For example, a family doctor in the UK gets paid more than US$200 000 per year, which is more than 13 times the Ghana (2005) Burkina Faso (2006) Zambia (2005) US$ US$ PPP 17 208 31 663 ·· 4128 7596 5760 12 557 4128 7596 5097 11 113 US$ PPP PPP Doctor 14 616 35 648 Midwife 5580 13 610 2873 (male) 2443 (female) 7556 (male) 6426 (female) Nurse 4896 11 941 2454 (registered) 1871 (certified) 6454 (registered) 4921 (certified) Nigeria (2001) US$ PPP Annual pay ·· ·· ·· Ratio of salary to GNI per capita Doctor 32·5 ·· ·· ·· 40·0 ·· ·· ·· Midwife 12·4 ·· 6·7/5·7 ·· 9·6 ·· 11·1 ·· Nurse GNI per person 10·9 450 ·· 1093 5·7/4·4 430 ·· 1131 9·6 430 ·· 791 9·8 520 ·· 1134 PPP=purchasing power parity. GNI=gross national income. Data are from references 9, 10, 11, and 12. Burkina and Nigeria data are inflated or deflated from survey date to 2005 prices. PPP conversions made at 2005 rates using World Bank conversion rates. Figures include all monetary allowances, including income from per diems and local fee revenue, but exclude other private income and non-monetary benefits. Table 3: Selected data from surveys of health workers in Ghana, Burkina Faso, Zambia, and Nigeria 678 www.thelancet.com Vol 371 February 23, 2008 Health Policy staff, who would have been paid more than their local counterparts, were excluded from the survey. When these salaries were compared with Malawi’s GNI per person (US$800 in 2005), the ratio was 54 for nurses with international NGOs, and 36·5 for the nurses with local NGOs. These ratios were higher than those recorded for public-sector nurses in table 3. Finally, what about the pay of health workers compared with other professions? The 2006 World Health Report compared the salaries of doctors and nurses with those of engineers and teachers, respectively; however, it extracted data from the ILO’s annual Labour Inquiry, which was generally old, incomplete, and unreliable for countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Reliable data with which to make such comparisons would be useful, for example, to inform the debate about prioritising the pay of health workers over other professions because of the urgency of the health crisis. Human resource management One of the findings from the Zambian survey was that the pay structure was complex, and consisted of many different types of allowance (eg, for housing, on-call duty, recruitment, retention, and uniform up-keep); overtime and night duty payments; and various non-monetary benefits.11 Such a complex structure not only incurs heavy administrative costs, but could also lead to inconsistencies, feelings of unfairness and mistrust in the system, and subsequent reductions in motivation. Another issue is regular payment. The Zambian survey reported that 15% of staff had not always received the salary payment that was due to them; 80% had received late payments; and 10% of staff had had to pay a so-called expediter’s fee to obtain their salaries.11 In Ghana, 40% of respondents had not received their allowance for additional duty hours regularly.10 Such tardiness is likely to discourage feelings of loyalty and commitment in employees of the public-sector health system. A third issue is the progression in pay over an individual’s working career. In Burkina Faso, pay did not increase with the length of service in the public sector.9 By contrast, Ghanaian salaries increased by a factor of 1·7 over the working life of a doctor, and by 3·7 for midwives.10 The prospect of a progression in salary over time would be expected to improve retention of staff within the public sector, although no empirical data from sub-Saharan Africa exists to substantiate this hypothesis. Fiscal and macroeconomic factors In most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, increases in government expenditure would be needed to raise the overall number of health workers and to improve pay, in both absolute and relative terms. Prospects exist for increased allocation of government budgets to health, and increased revenue collection. Few African countries have reached the Abuja target of allocating 15% of their public budget to health,27 and in low-income countries, tax www.thelancet.com Vol 371 February 23, 2008 Ministry of Health ($US) Driver Addis Ababa University ($US) Midrange NGO ($US) US bilateral agency ($US) 20–45 24–48 70–120 120–450 General medical practitioner, MD, with 2 years of service 157–252 ·· 330–530 ·· Senior medical specialist or assistant Professor 273–420 352 Expert medical specialist or associate Professor 354–513 400 Programme manager 568–968 Officer 450–600 Public-health professional, PH or PhD 260 352 Health coordinator 744–1268 Associate Director 1200–1500 Professor ·· ·· 447 ·· Assistant Officer 450–600 ·· Data are from reference 14. $US calculated from an exchange rate of $1 to 8·5 Birr. Table 4: Monthly salary differentials between health workers in Ethiopia Government Non-governmental Private ($US) organisation ($US) for-profit sector ($US) Doctor 7525 9240 Clinical officer 1915 3400 17 050 ·· Midwife 1900 ·· 2500 Nurse 1865 2295 ·· Lab technician 1915 2800 6350 Lay counsellor ·· 2200 8760 Data are from reference 13. Table 5: Comparison of average annual salaries by provider type in Zambia in 2004 revenues amount to an average of only 15% of GDP, compared with 30–40% in high-income countries. Government budgets could also increase as a result of economic growth, although the prospects of this are dismal in the poorest countries in sub-Saharan Africa. For these countries, any increase in public-sector employment and pay for health workers would require sustained external or donor financing. However, arguments against external financing include the volatility and unreliability of foreign financing, which could force developing countries to cope with large recurrent costs of salaries for health workers, if donors withdrew their aid. The IMF and finance ministries have argued that public spending needs to be capped, particularly in relation to non-traded goods and services such as domestic labour costs, to protect against inflation, currency appreciation, and fiscal instability.29 Another argument against external financing is that public budgets should be used to keep reserves of foreign currency high and to make debt repayments, rather than to spend more on the public sector. As a result, the IMF has redirected a large proportion of the increases in foreign aid to Africa into international currency reserves or domestic debt payments.28 Only 27% of new donor aid from 1999 to 2005 was actually designated to be spent on 679 Health Policy goods and services, and in some countries this was as low as 17%.28 Studies have shown that IMF policies hinder public spending and social investment, and that limits on wage bills prevent needs for education and health personnel from being met.29,30 Moreover, the macroeconomic rationale of the IMF’s restrictions on public spending on labour is not supported by evidence.31 Finally, some policy makers argue that government spending should be kept low as a means to liberalise labour markets, encourage a competitive low-wage environment, and attract private investment. These arguments implicitly suggest that investments in health and education are not pro-development, and ignore the need to build and sustain human capacity. Discussion We identified insufficient quality data about the salaries and income of health workers in sub-Saharan Africa to adequately study the association between the income of health workers and their morale, motivation, and choices about career and employment. The available survey data were limited by a lack of comparability, specificity, and detail, due to their methods and sample sizes. Policy questions for which data are needed include: How do countries determine the optimum balance between wage and non-wage expenditure within the health sector? What is the most effective response to the patterns of health-worker movement that aggravate inequities in health care? What package of financial and non-financial incentives is required to improve staffing of rural health facilities? To what extent do salaried health workers in the public sector generate additional income by other activities, and what is the effect on their performance within the health system? How important are per-diem payments in the public sector and how do they affect the availability and performance of workers in health facilities? What is the effect of the pay promotion structure on retention and motivation? Governments, WHO, ILO, research funders, and research institutions urgently need to generate the necessary data. They will need to invest in research, and perhaps more importantly, in regular surveillance and information systems. Definitions will need to be standardised, and the private sector needs a set of incentives and obligations to participate in data collection. Donors can promote strengthening of the human-resource departments of national health ministries. Improved data on salaries and incomes must also be complemented with better systems and more standardised methods to estimate the cost of living and to map the movement of health workers within and between countries. Efforts to adjust the skills mix and task allocations of health workers have focused on shifting tasks from doctors to clinical officers and nurses, and from nurses to lay workers and community health workers. Such shifts might 680 result in some cost savings and leave more highly skilled health workers to do more complex clinical and supervisory tasks. However, a system of fair pay is important for maintenance of morale and quality, and for reduction of attrition, especially since lay and community health workers are frequently volunteers and therefore receive little or no pay. To optimise the distribution and mix of health workers, some management of the labour market is necessary. Non-profit organisations and donor agencies need to consider the public good and coordinate with government on wages rather than competing for scarce health workers. Donors, NGOs, and Ministries of Health should instead cooperate. For example, non-government employers could allow their staff to work part time in government health services or teaching institutions. The recent drafting of a Code of Conduct by international NGOs to help ensure that their activities contribute to building public health systems is a welcome development.32 The draft code covers six areas of NGO activity, and explicitly recognises that NGOs can undermine the health system by employing health workers, managers, and leaders, and by isolating communities from formal health systems. Quite how such a cooperative model would work in practice is unclear, but a first step would be to reduce the competition between actors in the health system over labour. Governments must take the lead to recruit and retain skilled personnel within the public sector. The commitment by African Heads of State, in the Abuja Declaration, to spend at least 15% of government expenditure on health has only been achieved by four countries. Expenditure could also increase if countries worked to capture a higher proportion of GDP as public revenue. If governments committed to maximising their contribution to health systems, then donor organisations would have to assess how to support and finance the recurrent costs of public-sector health workers on a long-term basis. In Malawi, as part of the Sector Wide Approach, some donors are helping to fund an ambitious 6-year Emergency Human Resource Programme for the health sector, which includes an increase in government salaries. For the Programme to be supported, sustained, and replicated in similarly poor countries, the IMF, donors, and ministries of finance would need to relax budget limits and other macroeconomic policy restraints on public expenditure. Increased salary and income for the health workforce are not the only solution to the health workforce crisis in sub-Saharan Africa.33 Other solutions that need to be implemented concurrently include non-financial incentives to affect the motivation of health workers. Improving job satisfaction and career progression; enhancing working conditions and the quality of supervision; addressing on-the-job safety and security concerns; redressing the unavailability of good schools for children in rural areas; and improving the structure and management of the www.thelancet.com Vol 371 February 23, 2008 Health Policy payroll could all contribute to retention, motivation, and payment of health workers within the public sector, especially in rural regions where staffing problems are most acute. Contributors DMcC, SW, and SB coordinated writing this paper. SW contributed data from the Ghana survey, and TE from the Burkina Faso survey. SB extracted data from the Zambian and Nigerian surveys. SB and JG did PPP calculations. BP and BMcP contributed to historical analysis; DMcC contributed to data on salary differentials between the public and private sector; BB to macroeconomic and fiscal constraints; and SC to salary differentials between health workers and other professional groups. All authors have seen and approved the final version. 18 19 20 21 Conflict of interest statement We declare that we have no conflict of interest. References 1 Hertzberg F, Mausner B, Snyderman B. The motivation to work. New York, USA: Wiley, 1959. 2 Roenen C, Ferrinho P, Van Dormael M, Conceicao MC, Van Lerberghe W. How African doctors make ends meet: an exploration. Trop Med Int Health 1997; 2: 127–35. 3 Dubbledam R, Witter S, Silimperi D, et al. Independent review of Programme of Work 2006. Accra, Ghana: Ministry of Health, 2007. 4 Schiavo–Campo S, de Tommaso G, Mukherjee A. Government employment and pay in global perspective: a selective synthesis of international facts, policies and experience. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 1806. 1997. http://www.worldbank.org/html/ dec/Publications/Workpapers/WPS1700series/wps1771/wps1771.html (accessed Dec 13, 2007). 5 Heller, PS, Tait AA. Government Employment and Pay: Some International Comparisons. Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund, 1984. 6 Dräger S, Dal Poz MR, Evans D. Health workers wages: an overview from selected countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2006. http://www.who.int/hrh/documents/health_ workers_wages.pdf (accessed Jan 2, 2008). 7 Joint Learning Initiative. Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 2004. 8 WHO. World Health Report: Working together for health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. 9 Ensor T, Chapman G, Barro M. Paying and motivating CSPS staff in Burkina Faso: evidence from two districts. Initiative for Maternal Mortality Programme Assessment. Aberdeen, Scotland: University of Aberdeen, 2006. 10 Witter S, Kusi A, Aikins M. Working practices and incomes of health workers: evidence from an evaluation of a delivery fee exemption scheme in Ghana. Hum Resour Health 2007; 5: 2. 11 Ministry of Health, Zambia. The Zambia public expenditure tracking and quality of service delivery survey in the health sector. Zambia, Lusaka: Ministry of Health, 2007. 12 Das Gupta M, Gauri V, Khemani S. Decentralized delivery of primary health services in Nigeria. Survey evidence from the states of Lagos and Kogi. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank Development Research group, 2004. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTAFRICA/ Resources/nigeria_phc_text.pdf (accessed Jan 2, 2008). 13 Huddart J, Furth R, Lyons JV. The Zambia HIV/AIDS Workforce study: preparing for scale-up. operations research results. Bethesda, MD, USA: US Agency for International Development, 2004. 14 Davey G, Fekade D, Parry E. Must aid hinder attempts to reach the Millennium Development Goals? Lancet 2007; 367: 629–30. 15 Imani Development. Malawi NGO Remuneration Survey, 2005. Blantyre, Malawi: Imani Enterprise, 2005. 16 Lienert I, Modi J. A decade of civil service reform in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund, 1997. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.cfm?sk=2453.0 (accessed Jan 2, 2008). 17 Azangweo C. Case study 1: Ghana. In: McCallum N, Tyler V. Annex 2 of International experience with civil service censuses and civil service databases. London, UK: International Records Management Trust, 2001. http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/ civilservice/census.htm (accessed Jan 2, 2008). www.thelancet.com Vol 371 February 23, 2008 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Haque N, Aziz J. The quality of governance: “second-generation” civil service reform in Africa, Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund, 1998. http://www.imf.org/external/ pubs/CAT/doctext.cfm?docno=WPIEA1641998 (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Lindauer D. Government pay and employment policies and government performance in developing economies. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank, 1988. http://wbln0018.worldbank.org/ Network/PREM/PREMDocLib.nsf/58292AB451257BB9852566B4 006EA0C8/5EA2B2FCE14BD0AA852567130004665B (accessed Jan 2, 2008). International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Adjustment in Africa: reforms, results, and the road ahead. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press and World Bank, 1994. Egger R, Lipson D, Adams O. Achieving the right balance—the role of policymaking processes in managing human resources for health problems: issues in health services delivery. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2000. Ulreich R. Case Study 4: Sierra Leone. In: McCallum N, Tyler V. Annex 2 of International experience with civil service censuses and civil service databases. London, UK: International Records Management Trust, 2001. http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/ civilservice/census.htm (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Sawe D, Maimu D. Case Study 3: Tanzania. In: McCallum N, Tyler V. Annex 2 of International experience with civil service censuses and civil service databases. London, UK: International Records Management Trust, 2001. http://www1.worldbank.org/ publicsector/civilservice/census.htm (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Oluwu D. The role of the civil service in enhancing development and democracy: an evaluation of the Nigerian experience. Civil service systems in comparative perspective. Bloomington, IN, USA, April 5–8, 1997. http://www.indiana.edu/~csrc/olowu5.html (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Lienert I. Civil service reform in Africa: mixed results after 10 years. Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund, 1998. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/1998/06/lienert.htm (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Fedelino A, Schwartz G, Verhoeven M. Aid scaling up: do wage bill ceilings stand in the way. Washington, DC, USA: IMF 2006. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2006/wp06106.pdf (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Organisation of African Unity. Abuja declaration on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other related infectious diseases. Abuja, Nigeria: Government of the Organisation of African Unity, 2001. www. un.org/ga/aids/pdf/abuja_declaration.pdf (accessed Jan 2, 2008). IMF Independent Evaluation Office. The IMF and aid to sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund, 2007. http://www.ieo-imf.org/eval/complete/pdf/03122007/report.pdf (accessed Jan 2, 2008). CGD. Does the IMF constrain health spending in poor countries? Evidence and an agenda for action. Washington, DC, USA: Center for Global Development, 2007. http://www.cgdev.org/doc/IMF/IMF_ Report.pdf (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Marphatia AA, Moussié R, Ainger A, Archer D. Confronting the contradictions: the IMF, wage bill caps and the case for teachers. Washington, DC, USA: Action Aid USA, 2007. http://www.actionaidusa.org/imf_africa.php (accessed Jan 2, 2008) McKinley T, Hailu D. The macroeconomic debate: on scaling up HIV/AIDS financing. Brasilia, DF, Brazil: International Poverty Centre, UN Development Programme, 2006. http://www. jlica.org/debate/ScalingUpHIV_AIDSFinancing.pdf (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Health Alliance International. Global Connections, Health Alliance International Newsletter, September 2007. Seattle, WA, USA: Health Alliance International, 2007. http://depts.washington.edu/haiuw/ news/newsletters/2007-09.html (accessed Jan 2, 2008). Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med 2002; 54: 1255–66. 681