The Costs of Anti-Retroviral Treatment in Zambia

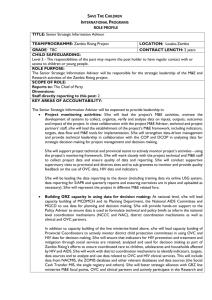

advertisement