Multiple Predictors of Maternal Sensitivity across the Transition

advertisement

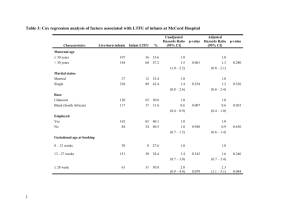

Multiple Predictors of Maternal Sensitivity across the Transition to Parenthood and Infant Social-Emotional Outcomes Kylene Krause, M.S., Alissa C. Huth-Bocks, Ph.D., Syreeta Scott, M.S., and Angela Joerin, B.A. Eastern Michigan University INTRODUCTION It has been well established in previous literature that sensitive maternal behaviors significantly impact important child developmental outcomes. In addition, sensitive maternal behaviors have been found to remain relatively stable over time, indicating that predictors of maternal sensitivity are a worthy topic of investigation. However, previous research lacks a full understanding of the various factors which promote early maternal sensitive behaviors. AIM: To explore prenatal and postnatal factors which may predict sensitive maternal parenting behaviors toward infants as well as infant social-emotional functioning. METHOD PARTICIPANTS: A community sample of pregnant women (N = 120) was recruited from public locations, programs, and agencies primarily serving low-income families. As part of a larger investigation, women participated in a 2 1/2 hour interview during their last trimester of pregnancy (T1) and received $25.00 compensation. During this interview, which often took place in the women’s homes, participants completed a semi-structured interview about their feelings about pregnancy and motherhood and verbally completed numerous questionnaires about their history, current and past relationships, psychosocial experiences, and general health. They also completed another, similar home visit when their infants were 1 year of age (T3). This visit lasted approximately 3 hours and women received $50.00 compensation. • Age: Mean = 26 (Range = 18 – 42, SD = 5.7) • Race/ Ethnicity: 47% = African American, 36% Caucasian, 18% = Other Ethnic Groups • Education: 20% = High School Diploma/ GED or less, 44% = Some College/Trade School, & 36% = College Degree • Monthly Income: Median = $1,500. • Family Status: 64% = Single Parents 30% = First Time Mothers MEASURES: 1 – Maternal Sensitivity. The Mini Maternal Behavior Q-sort (Bailey, Bisceglia, Roche, Jenkins, & Moran, 2009; Pederson, Moran, & Bento,1999) is a 25-item Q-sort (sorted into 5 categories of 5, from very much unlike the mother to very much like the mother) designed to assess the level of sensitivity shown towards the infant. The Q-sort is completed by trained researchers following the T3 home visit. Sensitivity scores are based on the correlation between the participants’ sort and an “ideal” sensitivity sort. 2 – Child Abuse Potential. The Brief Child Abuse Potential Inventory (BCAP; Ondersma, Chaffin, Mullins, & LeBreton, 2005) is a 34-item questionnaire that assesses dimensions believed to be related to risk for child abuse such as parental rigidity, loneliness, and general distress. The 24-item Abuse total collected during T1 was used for this investigation. 3 – Knowledge of Infant Development. The Knowledge of Infant Development Inventory (KIDI; MacPhee, 1981) is a 20-item multiple-choice questionnaire, collected at T3, designed to assess adults’ knowledge of typical child development and parenting of children from birth to 2 years. In this study, we used the proportion of correct responses to represent mothers’ knowledge of infant development. 4 – Parenting Daily Hassles. The Parenting Daily Hassles questionnaire (PDH; Crnic & Greenberg, 1990) is a 20-item multiple choice questionnaire designed to measure a parent’s perception of the frequency and intensity of the daily hassles of parenting. Each item is rated on how often the events happen (rarely, sometimes, a lot, or constantly) and then rated on a 1 to 5 scale of how much of a hassle the event is (1 = low, 5 = high). 5 – Infant Social-Emotional Problems. The Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA; BriggsGowan et al., 2004) is a 42-item multiple choice questionnaire of the social and emotional problems and competencies of children between the ages of 12 and 36 months of age. Items are rated as 0 = not true/ rarely, 1 = somewhat true/ sometimes, and 2 = very true/ often. Only the total problem scale was used in this investigation. RESULTS Table 1. Descriptive Data for Study Variables Measure Mean .41 6.4 Standard Deviation .43 5.0 KIDI .75 .15 .25 1 0 -1 N/A PDH Frequency 39.9 8.3 22 62 20 - 80 .81 PDH Intensity 37.5 12.2 20 78 20 - 100 .88 BITSEA 11.1 5.7 1 38 0 - 62 .77 Maternal Behavior Q-set BCAP Minimum Maximum Possible Alpha Range -.82 1.0 -1 - 1 N/A 0 21 0 – 24 .81 Table 2. Correlation Matrix for Study Variables Q-Set BCAP KIDI Q-Set 1.000 BCAP -.258* 1.000 KIDI .233* -.199* 1.000 PDH Freq. -.064 .190* PDH Freq. PDH Intens. BITSEA -.052 1.000 .264** -.127 .814** 1.000 BITSEA .257** -.412** .402** .404** Table 3. Predicting Maternal Sensitivity Variable BCAP KIDI PDH Intensity Adjusted R2 F Value β -.180 .176 -.161 .101 5.289 Child Abuse Potential Maternal Sensitivity Knowledge of Infant Development Infant SocialEmotional Functioning Intensity of Parenting Hassles PDH Intens. -.232* -.209* Figure 1. Mediation Models Tested 1.000 * p < .05 ** p < .01 Significance p = .056 p = .056 p = .083 Three different mediation models were tested with maternal sensitivity as the mediator, infant socialemotional functioning as the dependent variable and either child abuse potential, knowledge of infant development, or intensity of parenting hassles as the independent variable. Results from three sets of regression analyses showed that no mediation was found in any of the models. .002 • Table 1 displays descriptive data for all study variables. • Table 2 shows the correlations between all study variables. Greater maternal sensitivity was significantly related to lower child abuse potential, greater knowledge of infant development, lower intensity of parenting daily hassles, and lower infant social-emotional problems. • Table 3 presents the results of a multiple regression predicting maternal sensitivity. Together, child abuse potential, knowledge of infant development, and intensity of daily parenting hassles accounted for 10% of the variance in maternal sensitivity. The main effects of all three predictors individually approached significance in predicting maternal sensitivity. • Table 4 presents the results of a multiple regression predicting infant social-emotional functioning. Together, child abuse potential, knowledge of infant, daily parenting hassles, and maternal sensitivity accounted for 30% of the variance in infant social-emotional problems. Knowledge of infant development and the frequency of daily parenting hassles were the strongest individual predictors. Table 4. Predicting Infant Social-Emotional Functioning Variable β Significance BCAP KIDI PDH Frequency PDH Intensity Sensitivity Adjusted R2 F Value .095 -.349 .303 .072 -.067 .303 10.924 p = .258 p = .000 p = .030 p = .616 p = .437 .000 DISCUSSION This study examined predictors of maternal sensitivity that have not received much attention in the literature. Correlational results suggested that greater maternal sensitivity was significantly related to lower child abuse potential, greater knowledge of infant development, and lower intensity of parenting daily hassles. When considered simultaneously, these three factors together predicted 10% of the variance in maternal sensitivity. This is a relatively small effect. Thus, future research should continue to explore predictors of maternal sensitivity as it appears that other factors have significant contributions. However, predictors that could be identified prenatally might be especially important to investigate. No mediation was found in any of the three models tested. Instead, regression analyses suggested that knowledge of infant development, child abuse potential, and intensity of parenting hassles are (along with maternal sensitivity) important predictors of infant social-emotional problems. Correlational results suggested that increased infant social-emotional problems were significantly related to greater child abuse potential, lower knowledge of infant development, higher frequency and intensity of parenting daily hassles, and lower maternal sensitivity. When considered simultaneously, these five factors together predicted 30% of the variance in infant social-emotional problems. These results indicate that these five factors, and especially knowledge of infant development and subjective experiences of parenting, are important factors to consider when developing early intervention programs aimed at improving infant social-emotional functioning.