Maternal Depression, Sensitivity, Child Abuse Potential, and Parenting Stress

Maternal Depression, Sensitivity, Child Abuse Potential, and Parenting Stress as Predictors of Perception of Infant Emotion

Kristine Cramer, Melissa Swartzmiller, Alissa Huth-Bocks & Ana Tindall

Eastern Michigan University

INTRODUCTION

A mother’s ability to interpret infant emotions is crucial for healthy infant development (Weinberg et al., 2006). Depressed mothers and mothers at highrisk for child abuse display poorer emotion recognition skills overall than non-depressed and low-risk mothers (Balge & Milner, 2000; Weinberg et al., 2006). Exactly how infant emotion appraisals differ between these groups remains unclear; some studies indicated a mood congruency effect

(Leppanen et al., 2004), while others suggest a tendency for some mothers to attribute clearly positive or negative appraisals to ambiguous or neutral expressions (LeMoult et al., 2009).

Parenting stress has also been examined in relation to child abuse potential and depression (Balge &

Milner, 2000), but limited research exists on how the former construct influences perception of infant emotion. Lohaus, Keller, Ball, Elben, and Voelker

(2011) suggest that maternal responses (including maternal sensitivity) also differ depending on contextual factors, such as positive or negative infant cues. Limited research exists on the perception of infant emotion in low-income, high risk samples.

AIM: To examine how prenatal and postpartum factors predict mothers’ perception of infant emotion at 1 year post-partum in a racially diverse, high risk sample.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS:

Participants in this study include 120 mothers in an ongoing longitudinal study examining the transition to parenthood in a primarily low income sample.

• At study entry, participants’ ages ranged from18 to

42 ( M = 26, SD = 5.7).

• Forty-seven percent of participants are African

American, 36% are Caucasian, 13% are Biracial, and 4% belong to other ethnic groups.

• Sixty-four percent of participants are single (never married), 28% married, 4% separated, and 4% divorced, and 30% are first time mothers.

• 20% percent of participants have a high school diploma/GED or less education, 44% have some college or trade school, and 36% have a college degree.

• The median monthly income for participants is

$1,500 (range = $0 - $10,416).

• Eighty-eight percent receive services from WIC,

62% receive food stamps, 90% receive Medicaid,

Mi-Child, or Medicare, and 20% receive public supplemental income.

PROCEDURE/MEASURES:

Data from the first three waves [pregnancy (T1), 3 months postpartum (T2), and 1 year postpartum

(T3)] of the study were examined. T1 and T3 were in-home interviews; T2 interviews were conducted via telephone.

1 - Child abuse potential was assessed at T1 using the Brief Child Abuse Potential Inventory (B-

CAP; Ondersma, Chaffin, Mullins, & Lebreton,

2005). The B-CAP is a 34-item questionnaire that assesses dimensions believed to be related to risk for child abuse such as parental rigidity, loneliness, and general distress ( α = .86) .

2 - Maternal depression was measured at T2 using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

(EPDS; Cox et al., 1987; α = .84

) & at T3 using the

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al.,

1996; α = .90

).

3 - Parenting stress was examined at T3 using the

Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin,

1995). The PSI-SF is a 36-item self-report of stress in the parent-child relationship that allows for the identification of at-risk dyads ( α = .88) .

4 - Maternal sensitivity was rated in the home by observers at T3 using the short version of the

Maternal Behavior Q-Sort (MBQS; Pederson,

Moran, & Bento, 1999; Bailey, Bisceglia, Roche,

Jenkins, & Moran, 2009). The short Maternal

Behavior Q-Sort is a 25 item measure of observed maternal behaviors that were appraised by researchers throughout the in-home interview.

Items are sorted into 5 even piles ranging from “very unlike the mother” to “very much like the mother.”

5 Maternal perception of infant emotion was assessed at T3 using the IFEEL Pictures , a series of 30 color photographs of 1 year old infants displaying daily-occurring facial expressions (Emde et al., 1993). Responses can be scored using a categorical or dimensional approach. Categorically, responses are classified into 13 emotion categories

(surprise, interest, joy, contentment, passive, sad, cautious-shy, shame-guilt, disgust, anger, distress, fear, and other). Dimensionally, hedonic tone and arousal level ratings each range from 1 to 9, with lower tone ratings indicating a more negative response and lower arousal ratings indicative of a less-arousing response. The operating characteristics and psychometric properties of the

IFEEL Pictures were determined from a predominantly White, middle-class reference sample (Appelbaum, Butterfield, & Culp, 1993).

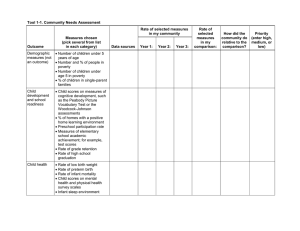

Measure

B-CAP (total)

EPDS (total)

BDI (total)

PSI (total)

Measures Totals

MBQS- Sensitivity

IFEEL-Tone

IFEEL- Arousal

Mean

6.42

5.05

10.79

67.57

.41

153.13

173.32

SD

4.97

4.36

8.31

14.24

.43

113.71

12.93

Correlational Findings

• Child abuse potential was negatively correlated with the overall tone of responses (r = -.19, p <

.05).

• Postpartum depression, assessed 3 months after birth, was positively correlated with more perceptions of surprise (r = .21, p < .01) and fewer perceptions of content ( r = -.21, p < .05).

• Parenting stress was positively correlated with perceptions of infant anger ( r = .24, p < .05).

• Maternal sensitivity was positively correlated with overall tone of more positive responses (r =

.24, p < .01).

• Summary: Post-partum depression and parenting stress predict perceptions of specific emotion categories. Child abuse potential and sensitivity predict overall tone of responses.

RESULTS

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Response Category Differences between Depressed (BDI total > 13) versus Non-depressed (BDI total < 14) Mothers

Category

T

Significance

Surprise

Interest

-.38

2.29

.71

.02

Joy

Content

Passive

Sad

-2.66

-.23

.04

.01

.82

.97

.35

Cautious-Shy

Shame-Guilt

-.94

1.01

-1.44

.92

.31

.15

Disgust-Dislike

Anger

Distress

Fear

-2.01

-.90

.26

.36

.05

.37

.80

*Significant findings indicated in bold italics.

DISCUSSION

T

-Test Findings

Average # of Responses per Category

Original

Reference

Sample

Current

Study

*Significant at p < .05 level. **Significant at p < .01 level.

• Mothers at greater risk for child abuse reported more negatively-toned appraisals. Interventions targeting mothers who are at risk for child abuse should focus on assisting mothers in perceiving and labeling a wider variety of infant emotion.

• The tendency to perceive more anger was associated with higher reported levels of parenting stress. Further research needs to be conducted investigating a possible mood congruency effect in parental stress and how it influences the perception of emotion; that is, stress and irritability may be projected onto the infant.

• Greater levels of observed maternal sensitivity were associated with more positively toned responses. Mothers who appeared more attentive and responsive to their infants’ needs seemed to perceive infant facial expressions in a more positive light overall. Interventions aimed at improving maternal sensitivity may also increase perceptions of positive emotionality in infants and vice-versa.

• Contrary to the mood congruency effect, mothers with depression at T3 were not more likely to report emotions in categories typically congruent with a depressed mood (such as sad, distress, or disgust-dislike) compared to nondepressed mothers. Instead, depressed and non-depressed mothers differed in how often they responded in more discrete emotion categories, such as joy and anger. Depressed mothers tended to perceive emotions that were clearer and associated with higher arousal than non-depressed mothers.