SECTION d Curriculum

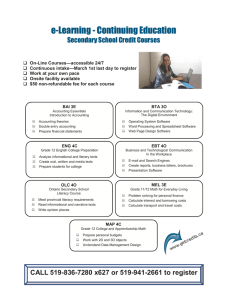

advertisement

SECTION d Curriculum Curriculum Description We know from our academic research and visits with educators across the country that Place-Based Education, integrated with state standards, has been proven to increase achievement levels. Learning that is rooted in place provides a rich, relevant context for knowledge that motivates students. We also know that lifelong learners have developed habits of mind, heart, and hands that support ongoing attainment of knowledge. Therefore, we have identified eight learning habits (used in professional development training at the Washtenaw Intermediate School District and included below) that support our mission of nurturing creative, critical thinkers who contribute to their communities: collaboration, social awareness, critical thinking, grit, creativity/resourcefulness, self-actualization, and health. To that end, every academic goal at the Boggs School has three purposes: 1) To ensure that each child develops the skills embedded in the Grade Level Content Expectations (GLCEs) and Common Core State Standards (CCSSs) in order to achieve college-readiness by graduation from the Boggs School 2) To encourage stewardship of place 3) To develop habits of mind, heart and hands for life-long learning Place-Based Education (PBE) PBE immerses students in local heritage, cultures, landscapes, opportunities and experiences, using these as a foundation for the study of language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and other subjects across the curriculum. PBE emphasizes learning through participation in service projects for the school and local community. Because PBE embraces a wide range of strategies, each project or unit of study looks different. There are, however, some very important similarities in successful PBE work. Successful PBE criteria (adapted from Sobel, 2005): Work is focused on relevant community issues Community organizations, schools, students, teachers, and parents all become partners in learning Community members become resources of the classroom Students are valued as productive, problem solving citizens of a community Students get out of the classroom and into the community Lessons and projects provide for student voice and student driving inquiry Experiences build meaningful, long-term relationships with community partners Student learning meets and exceeds state standards Experiences require sustained academic work (not a one-shot exposure) Work goes beyond a field trip. A field trip may be a critical component, but it should be only one component of the learning Allows students to see the “results” of their work in the school and community (examples include exhibitions of student work, changes in community policy as a result of work, something that students can point to and be proud of) Successful PBE benefits (adapted from Sobel, 2005): Partnerships and experiences lead to increased resources for schools and communities Experiences engage traditionally marginalized, disengaged students of all abilities Work solves community issues Experiences provide relevance and rigor in core content areas Work exceeds academic standards and can lead to students performing higher on standardized tests PBE is applicable and meaningful at any grade level PBE provides cross-curricular opportunities, and can lead to interdisciplinary teamwork Principles of Place-Based Education Learning takes place on-site, in the schoolyard, and in the local community and environment. Learning focuses on local themes, systems, and content. Learning is personally relevant to each learner. Learning experiences contribute to the community’s vitality and environmental quality; they support the community’s role in fostering global environmental quality. Learning is supported by strong and varied partnerships with local residents, organizations, businesses, and government. Learning is interdisciplinary. Learning experiences are tailored to the local audience. Learning is grounded in and supports the development of a love for one’s place. Local learning serves as the foundation for understanding and participating in appropriate regional and global issues. Common Core State Standards The Boggs School has been designing our curriculum to align our Place-Based approach with the CCSSs. PBE offers myriad opportunities for authentic learning experiences that cut across traditional disciplines. It is the responsibility of the classroom teacher, along with his or her team, to plan instruction that maintains the tenants of PBE while also addressing the requirements of the CCSSs. All of the instructors at the Boggs School will have a thorough understanding of both state and national standards and use this knowledge while collaboratively planning instruction. PBE is easily applicable to all traditional disciplines and content areas. In order to give a sense of what lessons at the Boggs School might look like, we have included a sample unit outline and a detailed lesson plan. (See Curriculum - Unit Outline) Essential Skills: Literacy Overview of Balanced Literacy Balanced Literacy is a framework for instructional planning and implementation of literacy education. It involves the use of observation, assessment, and work sampling to make instructional decisions; the structure of classroom delivery that moves through whole group, small group, and independent learning to build student competence and independence; and incorporates a balance of quality fiction and nonfiction materials to support instruction and learning in reading and writing. Untested literacy skills such as listening and public speaking are infused throughout a Balanced Literacy framework. The Boggs School will use the materials and framework of Fountas and Pinnell in implementing our Readers’ and Writers’ Workshops and Word Study. We will supplement our Writers’ Workshop with elements of Lucy Calkins’ writing curriculum and other related resources. Elements Balanced Literacy reading instruction incorporates the five foundation elements of reading (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary development, and comprehension) into an instructional framework based on Vygotsky’s “Gradual Release of Responsibility Theory.” The teacher’s goal is to support the growth and development of students so that they become independent learners. The teacher uses a structure of whole group, small group, and individual learning settings to identify and support the “Zone of Proximal Development,” the specific area of challenge where rigorous instruction can support and expand the learning of each student. Balanced Literacy writing instruction addresses the goal of fostering effective and lifelong writers, pairing creative writing and traditional convention instruction to this end. It is based upon four principles: students will write about their own lives, they will use a consistent writing process, they will work in authentic ways, and the process will foster independence. Each grade level has specific units of study tailored to meet developmental and curricular needs. Students have a large amount of choice in their topic and style of writing. The teacher acts as a mentor author, modeling writing techniques and conferring with students as they move through the writing process. Direct writing instruction takes place in the form of a mini-lesson at the beginning of each workshop and is followed by active writing time. Each workshop ends with a sharing of student work. Use of Observation and Assessment A teacher in a Balanced Literacy classroom uses observation and assessment to monitor the skill acquisition and development of children as they grow as readers and writers. This requires a deep and working knowledge of multiple ways to assess the foundational areas of reading and writing and having the flexibility to use assessment and observation data to make instructional decisions and modify instruction to meet the needs of each learner. It requires conversations between and among teachers at grade levels and across grade levels to discuss and problem-solve the reading and writing needs of students. Reading and writing will be assessed using a number of formative and summative assessment methods: Scantron Performance Series testing, Fountas and Pinnell’s Benchmark Assessment System, teacher-student book talks, guided reading notes analysis, writing sample rubric evaluation and comparison, and others. Structure of Classroom Delivery In a K/1 Balanced Literacy classroom, Readers’ and Writers’ Workshops, including Word Study, will be 8090 minutes per day. In 2/3 and 3/4, Readers’ Workshop, including Word Study, will be 90 minutes, while Writers’ Workshop will be an additional hour. Daily Schedule for Readers’ Workshop, K/1, 2/3, and 3/4 Whole Group Lesson - Introduction, Modeling, Setting the Purpose (Level 1 Example: Decoding Consonant Blends; Level 2 Example: Mapping the Plot of a Narrative) Small Group and Independent Learning - Small Group: Shared Reading, Guided Reading, Paired Reading, Literacy Circles and/or Intervention Groups - Independent Learning: Independent Reading, Literacy Centers, Ongoing Assessment Return to Whole Group Learning Daily Schedule for Writers’ Workshop, K/1, 2/3, and 3/4 Whole Group Lesson - Introduction, Modeling, Reinforcing a Strategy (K/1 Example: Telling Events in Order; 2/3 Example: Attention-Grabbing Leads) Independent Writing - Prewriting, Drafting, Revising, Editing, Final drafting, Publishing, Illustrating - Conferring o With Teacher o With Peers o Listen, help plan, give feedback, re-teach, reinforce strengths Whole Group Sharing - Presentation, Reflection, Feedback Weekly Schedule for Word Study, 2/3 and 3/4* Day 1: Mini-lesson; Choose~Write~Build - Teacher chooses a word pattern or group and shares with class (3/4 Examples: “Words With Silent –gh” or “Words That Come From Latin”). - Class cooperatively generates list of words that fit pattern or group. Each student chooses a predetermined number of words from the list for his or her own folder. Students supplement lists with a predetermined number of previously misspelled words from their individual “Words to Learn” lists. Students work independently, using magnetic letters and cookie sheets to build each of their weekly words three or more times. Day 2: Look~Say~Cover~Write~Check - Students work independently with special class-created slotted folders to follow the five steps in the title of the activity. - Students are given time to return to magnetic letters for words not mastered during this activity. Day 3: Buddy Test - Students are put in pairs to do a practice quiz of weekly words. - Students are given time to return to Day 1 and 2 activities for misspelled Buddy Check words. Day 4: Making Connections - Students participate in one of a wide variety of activities that will help them connect their words to whole language and real-life contexts. - Examples, depending on grade/ability level: o Writing a short story with weekly words included o Changing prefixes, roots, or suffixes to change meaning of words o Looking for weekly words and words in the same group in a newspaper o Creating a crossword puzzle using weekly words (advanced) Day 5: Final Test - Students test each other on weekly words. - Tests are graded by teacher. *Word Study lessons at K/1, including phonological and phonemic awareness, print awareness, alphabetic knowledge, alphabetic principle, decoding, reading practice with decodable text, irregular or high-frequency words, and reading fluency, are embedded seamlessly in Readers’ and Writers’ Workshops. Integration Balanced Literacy fits the curriculum at the Boggs School in a number of ways: 1) It is Place-Based Education. In addition to fantasy and other fictional text genres, students will have access to and be directed toward texts that relate to their daily lives: Realistic Fiction featuring characters that look and live like them, Informational Nonfiction that addresses real-life topics from their communities and/or based on their individual interests, and nontraditional texts that come directly from the community, including the work of Detroit poets, spoken-word art, and neighbor interviews, to name a few. 2) It depends on a Responsive Classroom. As in Math Workshop, literacy learning needs to exist in a community of discourse and constructive co-support. Students are asked to go beyond what they like, dislike, and think someone else should read or write and learn to support each other in their individual reading and writing skills and styles, drawing out the best in each other. The gradual release of responsibility is vital to a Balanced Literacy classroom as students are often working on different activities and skills at the same time; the Responsive Classroom is one in which students can define and act out ideas like “silent,” “quiet,” “collaboration,” “feedback,” and “respect.” 3) It serves our mission. In order to become creative, critical thinkers, students must be given opportunities to use creativity and critical thinking in their work. The “guided discovery” that Balanced Literacy employs allows students to experience a sense of responsibility for their own learning and a freedom to explore their own interests while still achieving skill attainment determined and facilitated by the teacher. In addition, literacy is a powerful tool in addressing the goal of having students contribute to the well-being of their communities. As future leaders, our students must be able to use the power of language to communicate with community members and outsiders, conduct research, critically assess the written and spoken expressions of community stakeholders, and advocate for his or her own beliefs. Balanced Literacy takes universal skills and allows BEC teachers and students to ground them in easily accessible and interesting contexts, fostering strong-minded and skilled citizens. Essential Skills Math Instruction at the Boggs School The Mathematics in the City program defines mathematics as “mathematizing”—the activity of structuring, modeling, and interpreting one’s lived world mathematically. Their mission is to support powerful mathematics instruction. They do this by guiding teachers towards developing their classrooms into mathematics workshops in which learners engage in inquiry, worthwhile mathematical tasks, proving their thinking and communicating it to their peers. That way, teachers help children develop a deep understanding of number and the operations of addition and subtraction in grades K-3; multiplication and division in grades 3-5; fractions, decimals, and percentages in 4-6, and on to algebra. The way this will look at the Boggs School is to have daily Math Workshops, which function much like Writing Workshops. Teachers begin by leading a ten- or fifteen-minute mini-lesson to highlight a certain computational strategy or to help children develop efficient mental math computation. These lessons are explicit and designed to offer children a way to notice strategies and patterns to solve problems. After a mini-lesson comes the heart of the workshop, which is the investigation-- teachers find situations or dilemmas and structure contexts for children to model and solve problems, all the while searching for patterns, asking questions, and discussing strategies. Often these situations can be found in the routine of the classroom. One example of this is having the kids figure out each day if there are enough children in the room for everyone to walk in pairs to recess. Naturally, investigating odd and even numbers every day. Or, to begin to facilitate the understanding of place value, a teacher might explain that the office manager needs help counting out handouts for each classroom and having the kids figure out how to bundle the handouts in stacks of ten and make a chart showing her how many packs and how many loose sheets she needs for each class in the school. As the students are presented with the problem and work together to make their charts, ideas and strategies are discussed on how to best count the handouts with some kids developmentally further along than others. That’s where the Math Congress part of the workshop comes in. After the investigating, the class convenes for a math congress, where students communicate their ideas, solutions, problems and conjectures with one another. Here is where students defend their thinking. This is often where students have “aha” moments, coming to understand their own thinking by being exposed to the different thinking of a classmate. Elements of a Math Workshop Mini-Lesson Investigation Math Congress Math in the City fits the curriculum at Boggs School in a number of ways: 1) It is Place-Based Education. It fits this description in that the investigations are meant to come out of the context of real world situations that the children can relate to, to be presented with problems and dilemmas they need to solve in order to do something concrete (e.g. someone in the school needs help figuring out a problem or we must figure out if we have enough sunflower seed packets to pass out to each of our neighbors). 2) It depends on a Responsive Classroom. Math workshop needs to exist in a community of discourse, in which students ask questions of one another and comment on one another’s work. Students are asked to explain their thinking, often to the whole class, so that the process of learning is visible. The Boggs School will use Responsive Classroom to establish a school culture that promotes learning. In a Responsive Classroom, students practice talking with and to one another each morning so they are not dependent on the teacher to be the sole listener in the room. That way, teachers can walk the line between participant and observer, helping her or him notice those children who could use more challenges to push their mathematical development. 3) It serves our mission. When an assessment with items that captured various levels of mathematizing was designed and given to third graders who were taught math traditionally as a list of procedures versus those taught by the Math in the City program, the answers were not significantly different, but those children who were in classrooms where number relationships and context were emphasized outperformed their peers in terms of using a number of strategies to compose and decompose numbers to make them friendlier to work with, make mental computations and answer problems within the context they were given. This is the kind of creative, critical thinking that the Boggs School is committed to and that our 21st century society needs. Habits of Heart, Mind, and Hands Learning at the Boggs School will be guided by the use of specific habits of mind, heart, and action that are central to our mission of nurturing creative, critical thinkers who are also compassionate and caring stewards of their environment. Developing these habits of mind, heart, and action are important to everyone at the school, not just students. Adults will be responsible for modeling these habits in practice, and teachers will incorporate the habits into each of their lesson plans, including making sure that they are engaging children intellectually, emotionally, and physically. Habits of Mind, Heart, and Hands Collaboration Social Awareness Critical Thinking Essential Questions Are we learning together? Are we valuing each other’s gifts? Is everyone getting what they need? From whose perspective are we seeing, hearing, reading? What questions do we have about this? What is the evidence? Is it reliable? Grit Are we dedicated, persistent learners? Do we know what we need to learn to gain answers to our questions? Creativity and Resourcefulness What else can we try? How can we transform ideas into an artful form of expression? Self-Actualization Do we know what we stand for? Are we enacting the best version of ourselves? Health What makes us healthy? How do we keep our lives in balance? Mastery What more can I learn? Have I taken any steps, even small ones, toward my goal? Curriculum: The Community Partners Program Overview To infuse our school with the arts, we will establish the Community Partners Program, an enrichment of the academic program that will utilize the skills of uncertified teachers from the community and our network of art, music, and movement educators to increase the learning opportunities for our students. Community teachers will emerge from the immediate neighborhood and from our grassroots networks to share their expertise within a boundless array of skills: carpentry, Suzuki violin, painting, gardening, food preparation, yoga, sewing, athletics, and beyond. In addition, community organizations will partner with us to provide before-, after-, and in-school enrichment opportunities. Community teachers will work in cooperation with certified classroom teachers, who will remain the “teachers of record.” Goals The aim of the Community Partners Program is to: 1) Enrich the academic experience of our students with diverse and extended learning opportunities in the arts 2) Honor and highlight the existing community resources and human assets of the neighborhood 3) Maintain and extend the large support network of the school 4) Model innovative educational arts programming that meets the needs of students and the community Many studies confirm our belief that “a caring and supportive relationship with an adult remains ‘the most critical variable’ predicting health and resiliency throughout childhood and adolescence” (Benard, 1991; Garmezy, 1993). We also believe that the benefits of intergenerational relationships are plentiful, both for children and older adults. We want the Boggs School to be the place where every student has numerous opportunities to find that caring and supportive relationship with an adult. Oftentimes, it is a classroom teacher. But personal connections are unpredictable and are not guaranteed. We want there to be as many opportunities as possible at the school academically and personally - to reach each child. Community members would be served by having their talents honored and utilized; and students would benefit from enrichment classes that strengthen their school experience. To implement this project, we will: 1) Identify the leaders in the community with skills that are widely respected and conduct background checks to ensure that they are safe for the student population. 2) Offer professional development to those individuals in our school culture and curriculum as well as in classroom management and lesson planning. 3) Partner community teachers with a classroom teacher for mentoring support, making sure that the learning corresponds to the school-wide anchor project (to be a gift to the community), which is required by our curriculum at the end of each trimester. 4) Develop high-quality before- and afterschool programming in partnership with Detroit Future Youth, extending the day by 3.5 hours. Partnerships The strength of the Boggs School lies in the nexus of relationships we have developed with others over two decades in our collective work to improve the city in which we all live. We are confident that we have a team of people who understand the Boggs’ legacy and are committed to preserve the mission and goals of the school. We see the Community Partners program as a potent exemplar of how to re-imagine education. We will contract with four regular community teachers for specific art, music, dance, and movement classes and numerous community teachers from the neighborhood to offer an array of programming for students. Each community teacher would be paid an hourly amount, consistent with a living wage. In addition to specific arts programs and community teachers, we have established relationships with partner programs, including SEMIS, Detroit Future Schools, Detroit Future Youth, InsideOut Literary Arts Project, and the Mt. Elliott Maker Space. We will also partner with other local organizations, including the Boggs Center to Nurture Community Leadership and Earthworks Urban Farm, although not directly under the Community Partners Program. These programs are described below. For a graphic depiction of our partnerships, please go this link: http://www.pearltrees.com/#/N-p=72281266&N-fa=7542472&N-f=1_7542472&N-s=1_7542472&N-u=1_1110050. 1) The Southeast Michigan Stewardship Coalition (SEMIS) – Eastern Michigan University (http://www.semiscoalition.org) The SEMIS Coalition facilitates school-community partnerships to develop students as citizenstewards of healthy ecological-social systems. The work of SEMIS is based on an EcoJustice framework that recognizes that social and environmental justice are not separate; they share the same cultural roots. SEMIS students, teachers, and community partners explore issues of social and environmental justice through learning focused on: i. ii. iii. iv. v. Engagement Care Critical Analysis & Inquiry Collaborative Problem-Solving Action, Advocacy, & Empowerment 2) Detroit Futures a. Detroit Future Schools (www.schools.detroitfuture.org) Detroit Future Schools partners graduates from Detroit Future Media with K-12 teachers to design and implement digital media arts-integrated curriculum. The goal of DFS is to use digital media arts to provide the project-based learning experiences that students need to understand and shape their worlds. Participating teachers and artists receive a full year of professional development support to implement and improve their instructional practices. b. Detroit Future Youth (www.youth.detroitfuture.org) Detroit Future Youth aims to strengthen and deepen youth social justice organizing in Detroit by partnering with youth programs that focus on social justice based education and multimedia creation and are using digital media to transform ourselves and our communities. Network members share a commitment to authentic youth-leadership development that fosters the future creators, problem-solvers and social change-makers our city needs. 3) InsideOut Literary Arts Project (www.insideoutdetroit.org) InsideOut Literary Arts Project engages children in the pleasure and power of reading and writing. The program places professional writers in schools to help students develop their self-expression and give them opportunities to publish and perform their work. 4) Mt. Elliott Makerspace (http://www.mtelliottmakerspace.com/) The Mt Elliott Makerspace is a community workshop where people make, tinker, and learn together. They do this in order to strengthen themselves and their communities. Based on the needs and passions of the Southeast Detroit community, the Mt. Elliott Makerspace concentrates on learning experiences and entrepreneurial opportunities related to transportation, electronics, digital tools, wearables, design & fabrication (future), food (future), and music & arts (future). Sustainability The Boggs School team will go through an evaluation process at the conclusion of the school year to determine the next year’s iteration of the program. If it is determined that we want to continue the program as-is or with revisions, we will assess whether it can be funded through our regular per-pupil state aid or whether we will need to seek outside funding. Evaluation Our criteria for a successful program is as follows: 1) We will see a vibrant, engaging, and rigorous learning community where students are developing strong and positive relationships with one another as well as at least one other adult in the school besides their classroom teacher. 2) We will experience high attendance numbers (a daily average of 95% or higher) because children are excited to be in school. 3) Students will create exceptional digital media projects with Detroit Future Schools that benefit the community and poetry with InsideOut that demonstrates a rich understanding of the school theme of “Home”. 4) School curriculum and classroom lessons are exemplars of excellent practices and supported by collaborations between classroom and community teachers. 5) Students will demonstrate the Eight Habits of Mind, Heart, and Hands, both in their regular classrooms and in classes with the community teacher. This will be measured using the transcription method developed by Detroit Future Schools as well as with a rubric developed in collaboration with SEMIS based on its existing self-assessment rubric for schools. We are also in the process of developing program evaluations with the Great Lakes Stewardship Initiative (GLSI), the statewide umbrella organization of which SEMIS is the southeastern hub, which has chosen us as a case-study for their program evaluation plan currently in development. The GLSI, a place-based institution, will inherently include community input in the evaluation process they are designing. In addition, we will measure the effectiveness of our program through child and parent satisfaction surveys and teacher evaluations and feedback. Community is a pillar of our school, and community members will be included at every phase of our school’s development and revision. Our anecdotal findings will be shared informally and periodically at community gatherings, while our formal evaluation results will be disseminated through our annual report to families and the community at the conclusion of the school year. We will strive to bring breadth and depth to our programming as we refine our process, extending this program to older students as our students age and to young children as we add an early childhood program in future years. Boggs School Essential Skills: Reading, Writing, and Mathematics There are essential skills that all students must master in order to become competent and lifelong learners. Students who master these skills will experience a greater degree of engagement and enjoyment in all of these subjects. The following charts show our commitment to the essential skills of reading, writing, and mathematical thinking. Essential Skill: Reading Curriculum Components Resources Assessment Aural: Teachers read aloud to nurture the whole class’ enjoyment of literature and teach reading comprehension skills. Texts: Guided Reading, Fountas and Pinnell Formative assessments through guided reading with teacher Guiding Readers and Writers (Grades 3-6): Teaching Comprehension, Genre, and Content Literacy, Fountas and Pinnell Diagnostic Benchmark Assessments Verbal: Students have regular opportunities to discuss books with classmates, teachers, and other adults. Interpretive: Students use reading experiences to make connections between texts, between text and place, and between text and self. Materials: High quality literature of multiple genres, written by notable authors is used to enrich the lives of children and their appreciation of literary arts. Individual: Silent reading time is consistently given. Integrated: Students have shared literacy experiences regardless of reading level. Learning Record MEAP Teaching for Comprehending and Fluency: Thinking, Talking, and Writing about Reading, K8, Fountas and Pinnell Strategies for Literacy Education, Wiesendanger Mosaic of Thought, Zimmerman and Keane Websites: www.ncte.org www.readwritethink.org www.readworks.org Essential Skill: Writing Curriculum Components Resources Assessment Process Orientated: Through dedication to the writing process: prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing; minilessons emerging from student writing; and reading related to writing experiences. Texts: The Art of Teaching Writing, Calkins Frequent formative assessments through teacherstudent writing conferences The Writing Workshop, Calkins and Harwayne Published work taken through the writing process The Conferring Handbook, Teacher Led: Through one-on- Calkins, Hartman, and White one teacher-student conferences, charting progress Writing Workshop: The over time. Essential Guide, Fletcher and Portalupi Peer Oriented: Through time to orally share writing with Craft Lessons: Teaching classmates. Writing K-8, Fletcher and Portalupi Expert Oriented: Through the analysis of published authors’ Non-FictionCraft Lessons: writing techniques. Teaching Information Writing K-8, Portalupi and Fletcher Product Oriented: Through the publication and celebration Websites: of student writing. www.ncte.org www.readwritethink.org Individual: Through quiet blocks of time given for writing exploration. Writing Portfolio Diagnostic Writing Assessment MEAP Essential Skill: Mathematical Thinking Curriculum Components Resources Math Workshop Texts: Ongoing formative assessment Elementary and Middle School including: Mathematics: Teaching Developmentally, Van de Walle - Periodic formative quizzes Cooperative learning and problem-solving skills Inquiry-based data collecting and analysis Problem-solving approaches to mathematics Math Journaling Calendar Math Assessment Young Mathematicians at Work: Constructing Number Sense, Addition, and Subtraction, Fosnot & Dolk - One-on-one task assessment notes Websites: www.nctm.org www.mitcccny.org Pre- and post-tests for each trimester’s units of study - Timed skills practice quizzes MEAP Place-Based Education in Action: Stories from the Field Finding the Alphabet All Around Town Our team has traveled across the country visiting, observing, and experiencing schools that use PlaceBased Education. On our trip to Forest Grove Community School in Forest Grove, Oregon, one of the most exciting examples of a Place-Based product was a professionally done alphabet photo book completed by the youngest students. Sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce, cameras were donated to the kids as they traveled through town taking pictures. They were specifically looking for places and things from the community that fit the alphabet letter they were assigned. Once they’d taken a picture they loved that captured their letter, they wrote a poem to go with their picture. This project has all the elements of effective Place-Based Education: the children must go into the community to complete the assignment, thereby establishing in them a sense of place and knowledge about that place; the work is sponsored by a community entity (such as the Chamber of Commerce) that supports and benefits from the school; students are learning core content material such as alphabetic awareness and the writing process; creative expression is ingrained in the assignment, allowing for individual strengths and talents to emerge; and there is a tangible product that demonstrates learning and contributes to the community. It is also a beautifully produced book, proving that the youngest amongst us are capable of producing quality work that can enrich all our lives. From Julia Putnam, The James and Grace Lee Boggs School Bats Need Houses, Too! While learning about the habitats and roles of bats in Michigan ecosystems, Mrs. Magos’ and Mrs. Nagle’s 2nd & 3rd grade students learned that humans activities are destroying bats’ natural habitats. The students and teachers felt they needed to do something about the problem. The first step was to create some places where bats can live without the threat of losing their homes. “My students wrote letters to many local area businesses and people who they thought might be willing to hang a bat house. In these letters, they tried to teach the recipients all that they had learned about bats and why they are of value to us and to our area. Many of my class’s bat houses have been hung: at a Preschool, an orchard, a farm, homes, etc. One is scheduled to be hung at the University of Michigan in the Spring.” Teacher Wendy Nagle The bat houses have also been hung in the homes of parents who volunteered to help the students construct the bat houses, as well as at the Subaru offices neighboring the school. From Ethan Lowenstein, Director, Southeast Michigan Stewardship Coalition and Professor of Curriculum and Instruction, Eastern Michigan University Sustainable Schools Project: What Does it Mean to be a Citizen in Our Neighborhood? When Lawrence Barnes Elementary School teachers Amy LaChance and Deirdre Morris developed the year long essential question for their 2nd and 3rd grade classes, "How do we care for the world and how does the world care for us?" it made sense to use the surrounding neighborhood as a springboard for broader study. This winter, LaChance and Morris are keeping close to campus but expanding the walls of their classroom to include the Old North End neighborhood and to use community members as teachers as they set about a new eight-week unit of study, "What does it mean to be a citizen in our neighborhood?" Key components of the Lawrence Barnes 2nd/3rd grade Neighborhood Unit: Mapping: Students kick off the unit with the creation of a hall-sized map of their city, plotting their school, roads, the river, lake, their homes and other points of community interest. Along the way, they learn map reading skills and begin to visualize their place in new and different ways. Literacy: Each week, students read neighborhood-themed informational text and fiction, exploring career books and stories about children around the world. After a field trip, students write personal narratives about the community resources they have visited. Photography: In a workshop with a local photographer, students examine the powerful stories photographs can tell. While viewing photos from a local newspaper, magazine advertisements and those taken by children in India and Haiti as part of the project Kids with Cameras, students learn to be mindful of each shot as they use photography as a tool to share their individual voices and perspectives. Field Trips: Equipped with clipboards, paper, pencils, inquiry skills and point-and-shoot cameras, small groups of students embark on Friday afternoon field trips throughout December and January. Each excursion has 2-3 planned points of interest where students gather information as they meet with community members, discovering new things about familiar and not-so-familiar places. Service-Learning: The unit culminates in a class book illustrated with photos, illuminated with narratives assembled as "An Old North End Neighborhood Guide," to be presented to new residents through the Vermont Refugee Resettlement Program. Once they have evaluated the positive attributes and opportunities for improvement in their community, students will be able to put their skills and knowledge into action. They will perform a service-learning project of their choosing to celebrate their work and their neighborhood. Possible projects include a neighborhood mural, assisting the food shelf, and a community green-up. By asking questions like "Where is our neighborhood? What makes our neighborhood function? What is the history of our neighborhood? What roles do people have in our community?" students begin to see the interconnectedness of their place. Students have acquired and practiced these new skills and have come to see and experience the familiar in a new light. Now they are ready to investigate new topics such as the natural world, human body systems, and the solar system. As students examine and value what is right outside the school door, they are not only empowered to understand their neighbors as resources, but also to begin their roles as a stewards of the neighborhood and the greater community. (Retrieved August 5, 2011 from http://www.promiseofplace.org/Stories_from_the_Field/Display?id=94) New City River Kids: On the Move and Making Waves! Teachers at the New City School, an independent school in St. Louis, Missouri, have been building strong connections in their curriculum between classroom activities and field studies. As part of this effort, they have taken things beyond simply engaging in outdoor learning by empowering the students to apply their growing knowledge to make a difference in the community. River Kids, an after school program made up of 4th through 6th graders at New City School, is making it a point to become better educated themselves and then educate others and take action on issues relating to river conservation. Carrying out this mission involves meeting on a regular basis to hear guest speakers, participating in stream clean-ups and re-vegetation projects to improve riparian zones, and taking part in community activities aimed at helping spread the word about river and water conservation issues. At the St. Louis Earth Day held in Forest Park (St. Louis' large urban park) each year, River Kids acts as a voice for river conservation by staffing its own booth. As part of this work, they use a stream table to demonstrate what they have learned about streams and rivers over the course of their studies. Integrating projects like this into both the regular school curriculum and the after-school program are powerful ways for students to make connections between the classroom and the "real world." Preparing students to teach others in an authentic context about the topics they have been studying also helps to deepen their own understanding. In addition to their Earth Day activities, River Kids also planned a benefit dinner at the City Museum to help raise money for the River Des Peres Watershed Coalition, a local volunteer organization working to improve the quality of our waterways and raise awareness about issues affecting St. Louis's streams and rivers. At the dinner, they had activities including games, raffles, music, and dancing for all ages. All of the proceeds from the dinner were given to the Coalition. Watching the students' level of investment and dedication in River Kids activities is inspiring. Students not only do a tremendous job of being advocates for rivers, but they play a role in nearly all aspects of the group's operations, including helping to keep track of the group's budget and serving on planning committees. This active, community-based learning environment sets the stage for students to grow up as "citizens making a difference," one of the New City School’s themes for learning. (Retrieved August 5, 2011 from http://www.promiseofplace.org/Stories_from_the_Field/Display?id=78) Issue S O U T H1EA STSeptember M IC H IG A N S 2010 T EW A RD SH IP C O A LIT SIO O UNT H EA ST M IC H IG AIssue N ST EW 1 A RD September SH IP C O A LIT 2010 IO N finding the mea ning of community in a pile of t ir es T r a cy D ur a ndet t o Teacher, H ope of D etroit Academy W HAT 4 C OMMUNITY ? why are there so many brownfields in our community and not the surrounding suburbs? For the past three years Hope of D etroit Academy (HO D A) and the Southeast Michigan Stewardship Coalition (SEMIS) have been working together to answer this question. Together with SEMIS, the students at Hope of D etroit have been participating in community-based projects to understand the importance of becoming stewards of their community. These projects included community mapping, identifying brownfields, starting a school recycling program, tire sweeps, creating schoolyard habitats and planning to make improvements to the playground next to the school. The issue of brownfields stirs up powerful questions about the connections between social and ecological injustices. IS The topic of local illegal dumping came up in these discussions. D uring the past year, our school petitioned the city to clean up the dumpsite next to our school. W e collected over 500 signatures from our parents, parents of children at a neighboring school and other community members. W hile we never received an official response from the city, a few weeks later, the garbage dumped on this site was cleaned up. Because our school is next to a major brownfield site, one of our first activities was to learn about them. W orking from curriculum supplied by Creative Change Educational Solutions, a SEMIS Community Partner organization, students learned about the twelve different types of brownfields (also known as “the dirty dozen”) and how they affect the community, both economically and environmentally. The students’ concern about illegal dumping inspired our Tire Sweep program. If you were to drive around the school’s neighborhood you would see several piles of illegally dumped tires. The students began questioning why this happens and suggested working on a solution. W ith the help of SEMIS and Southwest D etroit Environmental Vision (SD EV), HO D A’s tire sweep event was born. W orking within an EcoJustice framework we held classroom discussions, and as we explored the topic of brownfields, students at Hope considered the question: There were a series of activities involved in this community-based project. The students first learned how the dumped tires affect the environment and they interviewed local tire distributors to find out Responsive Classroom The founders of the Boggs School know from experience that in order to have a strong academic culture, we need a strong whole school culture. Our approach to a positive behavior system is to train all of our staff to use Responsive Classroom. Responsive Classroom (www.responsiveclassroom.org) is a series of teaching practices that promote community building in the classroom. It is based on the foundations of child development, awareness that social and academic learning are symbiotic, and the belief that all children want to learn and can learn. In the early 1990’s, the Northeastern Foundation for Children began working in Washington D.C public schools to share practical academic and social competencies. It was at this time, when they coined and defined the term Responsive Classroom as “The Responsive Classroom approach is a widely used, research-backed approach to elementary education that increases academic achievement, decreases problem behaviors, improves social skills, and leads to more high-quality instruction.” Using this approach at the Boggs School will help shape our school community and culture. At the Boggs School, we believe that developing and teaching a social curriculum is key in healthy development. The Responsive Classroom methods of establishing school culture, root teachers and students in a positive environment with positive communication. It provides the tools, language, and activities for academic and social success. This philosophy of respect for children and the realization that children need to learn and practice the social skills conducive to learning is a total complement to the Boggs School’s mission and vision for a school that’s truly responsive to community needs, and we are confident that it will help us to establish a culture where all children will academically, socially, and emotionally succeed. Unit Outline Theme Home – The inaugural theme for the Boggs School is Home. This is the overarching theme that we come back to throughout the year. All classes at all levels are working with the same main theme throughout the year. Home is a place, a space, and a venue where knowledge is applied. Home can denote a physical location of our origin and family. It can be understood in terms of community, neighborhood, school, city, and region. Paradoxically, it oscillates between permanence and ephemerality, concreteness and transience. Home transcends the physical. It is what we know and where we have the most influence. It is the middle of the bulls-eye with all else radiating outward like ripples in a pond. Home is the space where we experience love, joy, belonging, and feel safe. Home, we believe, is not only experienced but it is constructed, created, and fashioned. It is the place to which we always return. Sub-theme Family and Friends & Storytelling – Sub-themes act as the lenses through which we gain greater understanding of the main theme. We can use our family and friends and the stories we have about them to understand Home in a new and deeper way. Unit Plan This is a Kindergarten/First Grade unit plan. This unit is the particular application and integration of the sub-themes Family and Friends & Storytelling expressly for Kindergarten/First Grade students. Units are driven by 4 – 6 questions that students must answer, usually through a concrete outcome. The table below lists the driving questions and tangible outcomes for this unit. Questions Who is in our family? What makes a good friend? What are some similarities between our family and our friends? How do we find out about our family stories? What family story can I share? What non-human families exist near our school? Are we valuing each other’s gifts? Outcomes Family tree A friend map Venn Diagram Interview of Family Member Written and oral story ready for publication Chart of neighborhood animal “friends” Habit of Collaboration Activities Each of these outcomes is actualized through a series of activities. The activities lead to the successful completion of the outcome. In general, most outcomes are completed through 4 – 8 activities. Example Outcome: Interview of a Family Member Activities Discuss how we find out information that we want to know from people Define “interview” Discuss how to conduct a good class interview (e.g. taking turns, active listening) Brainstorm great interview questions Practice interviewing skills with peers Draft invitation to one or two guest family interviewees for more practice Write and send thank you letters to guest interviewees Each activity is connected to multiple CCSSs: Activity Discuss how we find out information that we want to know from people Define “interview” Discuss how to conduct a good class interview Research and brainstorm great interview questions CCSS SL.K.1. Participate in collaborative conversations with diverse partners about kindergarten topics and texts with peers and adults in small and larger groups. a. Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (e.g., listening to others and taking turns speaking about the topics and texts under discussion). b. Continue a conversation through multiple exchanges. 1st Grade extension: SL.1. 1c. Ask questions to clear up any confusion about the topics and texts under discussion. RI.K 4. With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about unknown words in a text. 1st Grade Extension: RI.1. 4. Ask and answer questions to help determine or clarify the meaning of words and phrases in a text. SL.K1. Participate in collaborative conversations with diverse partners about kindergarten topics and texts with peers and adults in small and larger groups. a. Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (e.g., listening to others and taking turns speaking about the topics and texts under discussion). b. Continue a conversation through multiple exchanges. 1st Grade extension: SL.1.1c. Ask questions to clear up any confusion about the topics and texts under discussion. W.K. 8.With guidance and support from adults, recall information from experiences or gather information from provided sources to answer a question. d. Understand and use question words (interrogatives) (e.g., who, what, where, when, why, how). e. Use the most frequently occurring prepositions (e.g., to, from, in, out, on, off, for, of, by, with). f. Produce and expand complete sentences in shared language activities. Practice interview skills with peers SL.K 1. Participate in collaborative conversations with diverse partners about kindergarten topics and texts with peers and adults in small and larger groups. a. Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (e.g., listening to others and taking turns speaking about the topics and texts under discussion). b. Continue a conversation through multiple exchanges. 1st Grade extension: SL.1. 1c. Ask questions to clear up any confusion about the topics and texts under discussion. SL.1. 3. Ask and answer questions in order to seek help, get information, or clarify something that is not understood. L. K. 2. Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English capitalization, punctuation, and spelling when writing. Draft invitation to one or two family members interviewees for whole class practice Write and send thank you letters to class visitors L.K. 2. Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English capitalization, punctuation, and spelling when writing. a. Capitalize the first word in a sentence and the pronoun I. c.Write a letter or letters for most consonant and short-vowel sounds (phonemes). d. Spell simple words phonetically, drawing on knowledge of sound-letter relationships. Ist Grade Extension: L.1.2 e. Spell untaught words phonetically, drawing on phonemic awareness and spelling conventions. Lesson Plans The Common Core State Standards present the skills that students will need in order to complete each activity. Lessons are designed to teach these skills and address the content expectations. Example Activity: Research and brainstorm great interview questions Lesson Plan Theme: Home Sub-theme: Family and Friends Unit: Kindergarten/First Grade Family and Friends Driving Question: How do we find out our family stories? Final Outcome: Interview of a family member Lesson Time and Setting: Two days (Day one: Morning Meeting, Guided Read Aloud. Day two: Morning Meeting, Writer’s Workshop, Project Work) Materials: Writing journals, chart paper, pencils, dry-erase easel, Tell Me a Story, Mama (picture book by Angela Johnson) Objectives: SW use language that is appropriate to his/ her audience; SW identify courtesy words; SW use courtesy words; SW identify interrogative phrases (e.g. Who, What, When, Where, Why) SW use interrogative phrases SW request information Vocabulary: Courtesy, Interview, Request. Introduction: Engage students in a discussion that situates this activity within the context of the larger subtheme and theme, addressing the following points: Home is the main theme for our entire school year, and we understand that the people in our homes have stories to tell about their own lives and childhoods. The stories of our family become our own stories. One way to understand the people in our home - and therefore our own story - is to ask them questions about themselves. Interviews are one way to question people about things we want to know more about. The thematic question students are currently working on is, “How do we find out our family stories?” To answer this question, students have discussed the people who they consider to make up their family. They have discussed different kinds of families, including ones that are not human. They have listened to stories about families and compared their friends to their family members. Students have listened to interviews of authors and have decided to interview someone in their own family to figure out a family story to tell at the end of the trimester. To conduct the interview, they will continue their research on good interview questions (begun while listening to excerpts of interviews of famous authors) and come up with a class list of possible questions to use when interviewing one family member at home. Instruction: Day One Morning Meeting (whole group) – Morning Message includes a review of Question Words in the message along with correct punctuation. Guided Read Aloud (whole group in circle on carpet)—Read Tell Me a Story, Mama by Angela Johnson. Ask children to notice what questions could produce the stories told by Mama. List the questions. Have students notice the question words used. Day Two Morning Meeting (Whole group)--Morning greeting has greeter asking a question. Sharing time includes an opportunity for children to answer the question they were greeted with. Writer’s Workshop (whole group in circle on carpet) – Review list of questions from yesterday’s story. Teacher notes: Comments make an observation, share information or an experience, or make a connection; Questions are used to find an answer or gather more information. Pose question: Do responses change depending on how a question is asked? Connect: Different question words provoke different responses. Some questions are simply answered with a yes or a no. Other questions inspire longer answers. Teacher asks students to model what questions they’d ask if they wanted to hear a story. Several students are invited up to role-play being asked different questions. Shared writing: What are some questions one could ask that would prompt a story versus a yes or no response? Pose question: How do we ask questions courteously? Guide students towards noticing the use of “courtesy” words. Connect courtesy to the concept of respect. Courtesy words include greetings like hello, titles like ma’am or sir, and other words like please, thank you, excuse me, and you’re welcome. Connect: Interviewing a family member may sound different than talking with them casually. Have students discuss how it might sound different when they are conducting an interview with a family member rather than just having dinner or watching TV with them. Shared writing: create list of words that can be used to show courtesy and respect. Pose questions: Are courtesy words appropriate when interviewing a family member? How will students use courtesy words when interviewing at home? Project Work Time (whole group on carpet; partners at work stations) – Have students work with their mixed-age partner at their individual workstations to think of possible questions they will ask at home for their interview. Connect: After students have listed possible questions orally or in their writing journals, reconvene the class on the carpet. Students share out some of their questions. Make sure questions are focused on content that would be appropriate to share in school. As partner-groups share possible questions the teacher helps them identify unique questions that haven’t already been posed by another group in order to gather a variety of information. Students put a star next to the questions they will ask. Assessment: Students gather in a whole group to debrief and share information about what they anticipate hearing based on the questions they’ve compiled. Informal Daily Assessment – Question and Answer: students identify common courtesy words and use them appropriately; students are able to demonstrate asking questions versus making comments. Possible Learning Record Material – Journal entry response to the Read Aloud book. Written list of interview questions: look for questions with appropriate punctuation, complete sentences. Mixed-Age Adjustments: Younger students focus on the oral language elements of the project (using courtesy words, making a request, speaking clearly and succinctly, etc.) while older students also incorporate writing (recording the content of the interview, writing journal entries in complete sentences using correct punctuation, etc.). Students are grouped in mixed-age groupings. Accommodations: Peer-pairings allow students who are as of yet unable to independently complete work experience success and complete the content of the lesson. Integration with Place-Based Education: At the end of the first trimester, the community celebration of learning will include an exhibition of the work the students have completed. This would entail a community art project where students will choose and display their best work of the trimester, be it a portrait of the person they interviewed (which would include a community member in the 2nd/3rd grade mix), an oral telling of their family/friend story that they’ve crafted into a performance piece, or a written publication of their family story. The exhibition would be presented at a community fair as a gift to the community and a public display of the “portrait mural”, where all stakeholders in the school would be invited so that they may ask questions of the students, honor and receive the gift of the students’ work. Schedule 7d: Core Courses and Learner Outcomes KINDERGARTEN MATHEMATICS LEARNER DOMAINS (CCSS) LEARNER OUTCOMES (CCSS) Counting and Cardinality Know number names and the count sequence. Count to tell the number of objects. Compare numbers. Operations and Algebraic Thinking Understand addition as putting together and adding to, and understand subtraction as taking apart and taking from. Number and Operations in Base Ten Work with numbers 11-19 to gain foundations for place value. Measurement and Data Describe and compare measurable attributes. Classify objects and count the number of objects in each category Geometry Identify and describe shapes. Analyze, compare, create, and compose shapes. Mathematical Practices 1. 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. 2. 2. Reason abstractly and quantitatively. 3. 3. Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. 4. 4. Model with mathematics. 5. 5. Use appropriate tools strategically. 6. 6. Attend to precision. 7. 7. Look for and make use of structure. 8. 8. Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning. ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS STRAND LEARNER DOMAINS (CCSS) LEARNER OUTCOMES (CCSS) READING: LITERATURE Key Ideas & Details RL K.1 With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about key details in a text. RL K.2 With prompting and support, retell familiar stories, including key details. Craft & Structure RL K.4 Ask and answer questions about unknown words in a text. RL K.5 Recognize common types of texts (e.g., storybooks, poems). RL K.5 Recognize common types of texts (e.g., storybooks, poems). Integration of Knowledge & Ideas READING: INFORMATIONAL TEXT Range of Reading & Level of Text Complexity Key Ideas & Details RL K.7 With prompting and support, describe the relationship between illustrations and the story in which they appear (e.g., what moment in a story an illustration depicts). RL K.9 With prompting and support, compare and contrast the adventures and experiences of characters in familiar stories. RL K.10 Actively engage in group reading activities with purpose and understanding. RI K.1 With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about key details in a text. RI K.2 With prompting and support, identify the main topic and retell key details of a text. RI K.3 With prompting and support, describe the connection between two individuals, events, ideas, or pieces of information in a text. RI K.4 With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about unknown words in a text. RI K.5 Identify the front cover, back cover, and title page of a boo Integration of Knowledge & Ideas RI K.6 Name the author and illustrator of a text and define the role of each in presenting the ideas or information in a text. RI K.7 With prompting and support, describe the relationship between illustrations and the text in which they appear (e.g., what person, place, thing, or idea in the text an illustration depicts). RI K.8 With prompting and support, identify the reasons an author gives to support points in a text. READING: FOUNDATIONAL SKILLS Range of Reading & Level of Text Complexity Print Concepts RI K.9 With prompting and support, identify basic similarities in and differences between two texts on the same topic (e.g., in illustrations, descriptions, or procedures). RI K.10 Actively engage in group reading activities with purpose and understanding. RF K.1 Demonstrate understanding of the organization and basic features of print. RF K.1.b Recognize that spoken words are represented in written language by specific sequences of letters. RF K.1.c Understand that words are separated by spaces in print. RF 1.d Recognize and name all upper- and lowercase letters of the alphabet. Phonological Awareness RF K.2 Demonstrate understanding of spoken words, syllables, and sounds (phonemes). RF K.2.a Recognize and produce rhyming words. RF K.2.b Count, pronounce, blend, and segment syllables in spoken words. RF K.2.c Blend and segment onsets and rimes of single-syllable spoken words. RF K.2.d. Isolate and pronounce the initial, medial vowel, and final sounds (phonemes) in three-phoneme (consonant-vowel-consonant, or CVC) words.*(This does not include CVCs ending with /l/, /r/,or /x/.) RF K.2.e Add or substitute individual sounds (phonemes) in simple, one-syllable words to make new words. Phonics & Word Recognition RF K.3 Know and apply grade-level phonics and word analysis skills in decoding words. RF K.3.a Demonstrate basic knowledge of letter-sound correspondences by producing the primary or most frequent sound for each consonant. RF K.3.b Associate the long and short sounds with the common spellings (graphemes) for the five major vowels. RF K.3.c P Read common high-frequency words by sight. (e.g., the, of, to, you, she, my, is, are, do, does). RF 3.d Distinguish between similarly spelled words by identifying the sounds of the letters that differ. RF K.3.d Distinguish between similarly spelled words by identifying the sounds of the letters that differ. WRITING Fluency RF K.4 Read emergent-reader texts with purpose and understanding. Text Types & Purposes W K.2 Use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing to compose informative/explanatory texts in which they name what they are writing about and supply some information about the topic. W K.3 Use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing to narrate a single event or several loosely linked events, tell about the events in the order in which they occurred, and provide a reaction to what happened. W K.5 With guidance and support from adults, respond to questions and suggestions from peers and add details to strengthen writing as needed. W K.6 With guidance and support from adults, explore a variety of digital tools to produce and publish writing, including in collaboration with peers. Production & Distribution of Writing Research to Build & Present Knowledge SPEAKING & LISTENING Comprehension & Collaboration Presentation of Knowledge & Ideas LANGUAGE Conventions of Standard English W K.7 Participate in shared research and writing projects (e.g., explore a number of books by a favorite author and express opinions about them). W K.8 With guidance and support from adults, recall information from experiences or gather information from provided sources to answer a question. SL K.1 Participate in collaborative conversations with diverse partners about kindergarten topics and texts with peers and adults in small and larger groups. SL K.1.a Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (e.g., listening to others and taking turns speaking about the topics and texts under discussion). SL K.1.b Continue a conversation through multiple exchanges. SL K.2 Confirm understanding of a text read aloud or information presented orally or through other media by asking and answering questions about key details and requesting clarification if something is not understood. SL K.3 Ask and answer questions in order to seek help, get information, or clarify something that is not understood. SL K.4 Describe familiar people, places, things, and events and, with prompting and support, provide additional detaiL SL K.5 Add drawings or other visual displays to descriptions as desired to provide additional detaiL L K.1 Demonstrate command of the grammar and usage when writing or speaking. L K.1.a Print many upper- and lowercase letters. L K.1.b Use frequently occurring nouns and verbs. L K.1.c Form regular plural nouns orally by adding /s/ or /es/ (e.g., dog, dogs; wish, wishes). L K.1.d Understand and use question words (interrogatives) (e.g., who, what, where, when, why, how). L K.1.e Use the most frequently occurring prepositions (e.g., to, from, in, out, on, off, for, of, by, with). L K.1.f Produce and expand complete sentences in shared language activities. L K.2 Demonstrate command of capitalization, punctuation, and spelling when writing. L K.2.a Capitalize the first word in a sentence and the pronoun I. L K.2.b Recognize and name end punctuation. L K.2.c Write a letter or letters for most consonant and short-vowel sounds (phonemes). L K.2.d Spell simple words phonetically, drawing on knowledge of sound-letter relationships. Vocabulary Acquisition & Use L K.4 Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases based on kindergarten reading and content. L K.4.a Identify new meanings for familiar words and apply them accurately (e.g., knowing duck is a bird and learning the verb to duck). L K.4.b Use the most frequently occurring inflections and affixes (e.g., -ed, -s, re-, un-, pre-, -ful, -less) as a clue to the meaning of an unknown word. L 5 With guidance and support from adults, explore word relationships and nuances in word meanings. L K.5 With guidance and support from adults, explore word relationships and nuances in word meanings. L K.5.a Sort common objects into categories (e.g., shapes, foods) to gain a sense of the concepts the categories represent. L K.5.b Demonstrate understanding of frequently occurring verbs and adjectives by relating them to their opposites (antonyms). SCIENCE STRAND LEARNER DOMAINS (GLCE) LEARNER OUTCOMES (GLCE) Science Processes Inquiry Process S.IP.00.11 Make purposeful observation of the natural world using the appropriate senses. S.IP.00.12 Generate questions based on observations. S.IP.00.13 Plan and conduct simple investigations. S.IP.00.14 Manipulate simple tools (for example: hand lens, pencils, balances, non-standard objects for measurement) that aid observation and data collection. S.IP.00.15 Make accurate measurements with appropriate (non-standard) units for the measurement tool. S.IP.00.16 Construct simple charts from data and observations. Inquiry Analysis and Communication S.IA.00.12 Share ideas about science through purposeful conversation. S.IA.00.13 Communicate and present findings of observations. S.IA.00.14 Develop strategies for information gathering (ask an expert, use a book, make observations, conduct simple investigations, and watch a video). Reflection and Social Implications Physical Science Force and Motion S.RS.00.11 Demonstrate scientific concepts through various illustrations, performances, models, exhibits, and activities. P.FM.00.11 Compare the position of an object (for example: above, below, in front of, behind, on) in relation to other objects around it. P.FM.00.12 Describe the motion of an object (for example: away from or closer to) from different observers’ views. P.FM.00.21 Observe how objects fall toward the earth. P.FM.00.31 Demonstrate pushes and pulls. Life Science Organization of Living Things P.FM.00.32 Observe that objects initially at rest will move in the direction of the push or pull. P.FM.00.33 Observe how pushes and pulls can change the speed or direction of moving objects. P.FM.00.34 Observe how shape (for example: cone, cylinder, sphere), size, and weight of an object can affect motion. L.OL.00.11 Identify that living things have basic needs. L.OL.00.12 Identify and compare living and nonliving things. Earth Science Solid Earth E.SE.00.11 Identify Earth materials (air, water, soil) that are used to grow plants. STRAND LEARNER DOMAINS (GLCE) LEARNER OUTCOMES (GLCE) History Living and Working Together SOCIAL STUDIES Use historical thinking to understand the past. K – H2.0.1 Distinguish among yesterday, today, tomorrow. K – H2.0.2 Create a timeline using events from their own lives (e.g., birth, crawling, walking, loss of first tooth, first day of school). K – H2.0.3 Identify the beginning, middle, and end of historical narratives or stories. K – H2.0.4 Describe ways people learn about the past (e.g., photos, artifacts, diaries, stories, videos). Geography The World in Spatial Terms Use geographic representations to acquire, K – G1.0.1 Recognize that maps and globes represent places. process, and report information from a spatial perspective. K – G1.0.2 Use environmental directions or positional words (up/down, in/out, above/below) to identify significant locations in the classroom. Places and Regions Understand how regions are created from common physical and human characteristics. Environment and Society K – G2.0.1 Identify and describe places in the immediate environment (e.g., classroom, home, playground). Understand the effects of humanenvironment interactions. K – G5.0.1 Describe ways people use the environment to meet human needs and wants (e.g., food, shelter, clothing). Civics & Government Values and Principles of American Democracy K – C2.0.1 Identify our country’s flag as an important symbol of the United States. K – C2.0.2 Explain why people do not have the right to do whatever they want (e.g., to promote fairness, ensure the common good, maintain safety). K – C2.0.3 Describe fair ways for groups to make decisions. Role of the Citizen in American Democracy K – C5.0.1 Describe situations in which they demonstrated self-discipline and individual responsibility (e.g., caring for a pet, completing chores, following school rules, working in a group, taking turns). Economics Market Economy K - E1.0.1 Distinguish between goods and services. K - E1.0.2 Describe economic wants they have experienced. K - E1.0.3 Recognize situations in which people trade. Public Discourse, Identifying and Analyzing Public Issues Decision Making, and Citizen Involvement K – P3.1.1 Identify classroom issues. K – P3.1.2 Use simple graphs to explain information about a classroom issue. K – P3.1.3 Compare their viewpoint about a classroom issue with the viewpoint of another person. Persuasive Communication About a Public Issue K - P3.3 Communicate a reasoned position on a public issue. K – P3.3.1 Express a position on a classroom issue. Citizen Involvement K – P4.2.1 Participate in projects to help or inform others. K – P4.2.2 Develop and implement an action plan to address or inform others about a public issue.