Bayh-Dole Act Turned On Its Head?

advertisement

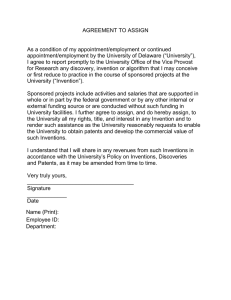

August 12, 2011 Practice Groups: Government Contracts and Procurement Policy Bayh-Dole Act Turned On Its Head? The Supreme Court Tells Government Contractors (And, Potentially, The Federal Government) They Do Not Automatically Get Rights In Federally Funded Inventions Introduction The Supreme Court recently held that the University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act of 1980, more commonly known as the Bayh-Dole Act (occasionally referred to herein as the “Act”), does not automatically vest title to federally funded inventions with federal contractors covered by the Act.1 This holding may come as a shock to some, including the U.S. Government, which argued in an amicus brief that the Court’s holding will turn “the Act’s framework on its head.”2 At the very least, the Court’s holding requires federal contractors to review their current policies and practices concerning employee assignments of inventions and nondisclosure agreements. Moreover, the Court’s opinion may even have unintended consequences with respect to the government’s rights in federally funded inventions. Background Before diving into the Court’s decision, a little background information may prove useful. Congress enacted the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980 in an attempt to establish a uniform system to allocate rights in federally funded inventions between the federal government and certain government contractors.3 Very generally, the Act and its implementing regulations allow small business and nonprofit government contractors to retain title to inventions conceived or first reduced to practice by the contractor during the performance of a government contract (such inventions are called “subject inventions”), subject to certain procedural requirements and government rights.4 The patent rights principles of the Act have been extended to large and for-profit businesses by President Ronald Reagan’s “Memorandum to the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies: Government Patent Policy,” issued February 18, 1983.5 Indeed, the Federal Acquisition Regulation (“FAR”), which applies to all government contractors (unless a statutory exception applies) states “[g]enerally, 1 Bd. of Trs. of the Leland Stanford Junior Univ. v. Roche Molecular Sys., 180 L. Ed. 2d *1, 2011 U.S. LEXIS 4183 (2011). 2 Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, at 11. 3 35 U.S.C. §§ 200, 210(a). 4 35 U.S.C. §§ 200 et seq.; 37 C.F.R. Part 401. 5 Despite the Presidential Memorandum, the Department of Energy (“DOE”) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (“NASA”) have authorizing statutes that generally enable them to take title to subject inventions made by large, for-profit companies. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 2182, 5908 (DOE), and 42 U.S.C. § 2457 (NASA). DOE and NASA, however, have the right to waive the patent rights statutes, under appropriate circumstances. See 10 C.F.R. Part 784 (DOE) and 14 C.F.R. Part 1245 (NASA). For example, contractors may apply to the DOE for an individual advance waiver of the patent rights statute (or DOE may grant a class waiver) and, if granted, the contractor (or contractors, if a class waiver) may retain title to any subject inventions made under the contract, subject to disclosure, election and filing requirements similar to those in the Bayh-Dole Act implementing regulations (including those in the FAR). See 10 C.F.R. § 784.12. Bayh-Dole Act Turned On Its Head? pursuant to 35 U.S.C. 202 and Presidential Memorandum and Executive order…each contractor may, after required disclosure to the Government, elect to retain title to any subject invention.”6 Pursuant to the Act’s implementing regulations, government contractors may retain title to a subject invention if the contractor discloses the invention within a certain amount of time of being conceived or first reduced to practice, affirmatively elects to retain title in writing to the government, and files an initial patent application by a set deadline.7 For each subject invention to which the contractor retains title, the federal government is entitled to a nonexclusive, nontransferable, irrevocable, world-wide, paid-up license to practice the invention or have the invention practiced on the government’s behalf.8 “If a contractor does not elect to retain title to a subject invention…the Federal agency may consider and after consultation with the contractor grant requests for retention of rights by the inventor subject to the provisions of this Act and regulations promulgated hereunder.”9 At least from initial outward appearances then, the Act arguably establishes an order of priority with respect to title to subject inventions, putting the contractor in the prime position, with the government next and the inventor last. Until recently, the U.S. Government (and Stanford) believed this was the case and that the Act provided a dependable system for allocation of priority to ownership of subject inventions. The Case With the above as context, we now turn to the facts and the Court’s opinion. The case involved a dispute over title to a subject invention conceived or first reduced to practice, at least in part, by an employee of Stanford utilizing a private entity’s facilities and technology. In the 1980s, the Cetus Corporation (“Cetus”) developed polymerase chain reaction (“PCR”) technology relevant to HIV/AIDS research.10 Stanford researchers, including Dr. Mark Holodniy, subsequently began collaborating with Cetus, some at Cetus’ facilities, on the potential uses of PCR.11 In connection with his employment with Stanford, Dr. Holodniy had signed a “Copyright and Patent Agreement” (“CPA”), in which he “‘agree[d] to assign’ to Stanford his ‘right, title and interest in’ inventions resulting from his employment at the University.”12 Subsequently, however, and in conjunction with a visit to Cetus to perform PCR research, Dr. Holodniy also signed a Visitor’s Confidentiality Agreement (“VCA”) with Cetus to gain access to its facilities. The VCA included an agreement that Holodniy “‘will assign and do[es] hereby assign’ to Cetus his ‘right, title and interest in each of the ideas, inventions and improvements’ made ‘as a consequence of [his] access’ to Cetus.”13 The research at Cetus, which was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, resulted in a subject invention using the PCR technology that allowed for the detection and measurement of HIV acids in blood samples.14 Dr. Holodniy later conducted successful clinical studies using the subject 6 FAR 27.302(b); 48 C.F.R. § 27.302(b). Similar to the Bayh-Dole Act, the clause at FAR 52.227-11, which generally is the applicable clause for non-Defense experimental, developmental or research work conducted by a large, for-profit contractor, allows the contractor to retain title to a subject invention, subject to disclosure, election and patent filing requirements, and, in such circumstances, provides the government with a license to practice the invention. If conducting such work pursuant to a contract with the Department of Defense, the applicable clause allowing a contractor to retain title is Department of Defense FAR Supplement 252.227-7038, which is similar in function to the FAR clause. 7 37 C.F.R. § 401.14(b) and (c). 8 37 C.F.R. § 401.14(b). 9 35 U.S.C. § 202(d) (emphasis added). 10 Leland Stanford Junior Univ., 180 L. Ed. 2d at *9. 11 Id. 12 Id. 13 Id. 14 Id. at *9-10. 2 Bayh-Dole Act Turned On Its Head? invention at Stanford after which Stanford filed patent applications in compliance with the Bayh-Dole Act resulting in three patents.15 In 1991, Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. (“Roche”) purchased the PCR-related assets from Cetus, including all rights purportedly assigned by Dr. Holodniy, and began manufacturing HIV detection kits.16 Stanford subsequently filed a lawsuit alleging that the detection kits infringed on the university’s patent rights to the subject invention.17 The Supreme Court, affirming the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, held that the Bayh-Dole Act did not operate to automatically vest title with Stanford, even if the university had complied fully with the Act.18 The Court found that the Act was not intended to, and does not, supersede the wellestablished rule of law that rights in an invention belong to the inventor, absent an express, effective assignment of those rights.19 In this regard, the Court said “[t]he Bayh-Dole Act does not confer title to federally funded inventions on contractors or authorize contractors to unilaterally take title to those inventions; it simply assures contractors that they may keep title to whatever it is they already have.”20 According to the Court, the Bayh-Dole Act comes into play only when an invention already belongs to the contractor.21 The Court’s holding relied in part on the finding that the Act does not contain unambiguous language divesting the inventor of title in his/her invention in favor of another (such as the contractor or government), as is the case with other laws with such a purpose.22 Justice Breyer issued a dissenting opinion, joined by Justice Ginsburg, on the ground that the answer to the actual issue on appeal turns on matters not briefed by the parties or considered by the Court (i.e., interpretation of the assignment language) and, thus, the judgment of the Federal Circuit should be vacated and the case should be remanded for further argument.23 In reaching its holding, the dissent did, however, also express reservations about the majority’s holding. More specifically, the dissent, after considering the goals of the Act, stated that “I cannot so easily accept the majority’s conclusion -- that the individual inventor can lawfully assign an invention (produced by public funds) to a third party, thereby taking that invention out from under the Bayh-Dole Act’s restrictions, conditions, and allocation rules.”24 Fallout The Court’s holding subjects the priority allocation system of the Act to the private contracting practices of government contractors and their employees. Unless and until the subject invention actually belongs to the contractor through a valid and effective assignment from the employee inventor, the Court made clear that a contractor -- as opposed to an inventor-employee -- may not have rights in a subject invention pursuant to the Act. Even more troubling, the Act and any certainty it traditionally may have provided to contractors ultimately is subject to the diligence of the contractor’s researchers and other employees in properly executing (or not executing) assignment and 15 Id. Id. 17 Id. at *10. 18 Id. at *13-14, 17. 19 Id. at *12-15. The Court did not address the holding of the Federal Circuit regarding the effectiveness of Dr. Holodniy’s assignment to Stanford. Stanford University claimed that Dr. Holodniy had no rights to assign to Cetus because the research was federally funded and the Bayh-Dole Act gave the university superior rights in the invention. The Federal Circuit held that the language in the assignment to Stanford was nothing more than an agreement to assign rights in the future and, thus, the first effective present assignment was to Cetus. 20 Id. at *14-15. 21 Id. at *15. 22 Id. at *13-15. 23 Id. at *23. 24 Id. at *19. 16 3 Bayh-Dole Act Turned On Its Head? non-disclosure documents, which poses a risk -- after all, researchers often are more focused on conducting research than on administrative procedures. Interestingly, the holding also may have subjected the Federal government’s rights in subject inventions to the same uncertainty. If the Act does not control priorities unless and until the contractor has title, then the government arguably does not receive a license and/or any of the other rights provided by the Act until such time. The Act and the implementing regulations state that the federal government obtains a license only with respect to a subject invention in which the contractor retains title.25 This certainly would not be consistent with the intent of the Act, which states that one of its objectives is to “ensure that the Government obtains sufficient rights in federally supported inventions to meet the needs of the Government…”.26 Recommended Action If Congress disagrees with the Court’s conclusion regarding the intent behind the Act, it can take legislative action to clarify its true intent. Given the issues that the Court’s opinion potentially creates with respect to rights of the federal government in federally funded inventions, it is possible Congress may take some action. However, even if Congress believes the Supreme Court is mistaken, it is not certain that it will take action any time soon given the current issues swarming Capitol Hill. In the meantime, if a government contractor wishes to ensure protection of any rights it may obtain in subject inventions pursuant to the Act, it must make sure that it has a valid, present assignment of its employees’ rights in all inventions. Although the Supreme Court did not directly rule on the Federal Circuit’s holding regarding the validity of Stanford’s assignment language (i.e., whether “agrees to assign” any inventions resulting from his employment is merely a promise for a future assignment), it would be prudent, regardless of the jurisdiction in which the contractor is located, to ensure that it has presently effective assignments from all employees (e.g., “does hereby assign”), given the holdings in the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court. Moreover, contractors should conduct focused training for all employees with potential involvement in the performance of government contracts and the conception or reduction to practice of subject inventions. The training should cover the basics of patent rights under government contracting regulations and the company’s related policies and procedures, including signing (or not signing) assignments and non-disclosure agreements proffered by third parties. In particular, training should focus on ensuring that company employees carefully review and understand the implications of any nondisclosure agreements that they are asked to sign when they visit a third-party facility to conduct research or even for a technical interchange. In many instances, the value of the intellectual property developed under a government contract may have more value to the contractor than the contract itself. Thus, it is critical that contractors take all steps necessary to protect their rights in subject inventions, and any other intellectual property pertinent to contract performance, including technical data and even intellectual property developed at private expense. 25 35 U.S.C. § 202(c)(4); 37 C.F.R. § 401.14(b). Further, pursuant to the Act, the government may obtain title to a subject invention, if the contractor fails to disclose the subject invention, does not elect to retain title to the subject invention, or does not file required patent applications. See 35 U.S.C. § 202(c); 37 C.F.R. § 401.14 (b)-(c). These rights, however, also are at least implicitly contingent upon the contractor having title to the subject invention. If the Act does not operate to divest an inventor of title to his invention, as held by the Court, then it certainly cannot award title to the government. 26 35 U.S.C. § 200. 4 Bayh-Dole Act Turned On Its Head? Authors: Paul W. Bowen paul.bowen@klgates.com +1.214.939.4919 Robert J. Sherry robert.sherry@klgates.com +1.214.939.4945 5