The Impact of Recreational and Rural Residential Subdivisions

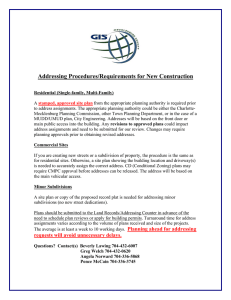

advertisement