Document 13562702

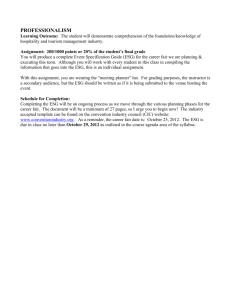

advertisement