HERE WE ARE. by Emily Forbes Browne

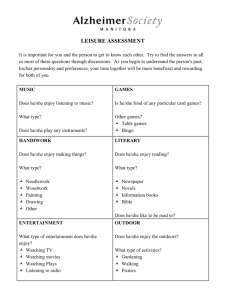

advertisement

HERE WE ARE. by Emily Forbes Browne A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Fine Arts in Art MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2011 ©COPYRIGHT by Emily Forbes Browne 2011 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Emily Forbes Browne This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citation, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to The Graduate School. Rollin Beamish Approved for the School of Art Vaughan Judge Approved for The Graduate School Dr. Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Emily Forbes Browne April 2011 iv LIST OF IMAGES Images Page 1. Father and Son, 2010, Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper, 128” x 84” ......9 2. Father and Son (detail) ...................................................................................10 3. Father and Son (detail) ...................................................................................11 4. Watching Them Both, 2011, Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper 258” x 89” (total installation) ...................................................................12 5. Watching Them Both (panel 1 of 4), Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper 114” x 42” . ..............................................................................................13 6. Watching Them Both (panel 2 of 4), Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper 114” x 42”................................................................................................14 7. Watching Them Both (panel 3 of 4), Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper 114” x 42”................................................................................................15 8. Watching Them Both (panel 4 of 4), Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper 114” x 42”................................................................................................16 9. Watching Them Both (detail of panel 1 of 4) .................................................17 10. Watching Them Both (detail of panel 3 of 4)................................................18 11. Watching Them Both (detail of panel 4 of 4)................................................19 12. Watching Them Both (installation detail) ....................................................20 13. Watching Them Both (installation detail) .....................................................21 14. Here Together, 2011, Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper, 126” x 94”....22 15. Here Together (detail) ..................................................................................23 16. Here Together (detail) ..................................................................................24 17. Here Together (detail) ..................................................................................25 18. Here Together (detail) ..................................................................................26 v LIST OF IMAGES – CONTINUED Images Page 19. Long History, 2010, Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper, 42” x 60” .......27 20. Long History (detail)....................................................................................28 21. Influence, 2010, Graphite, Pastel, Acrylic Ground and Charcoal on Paper, 30” x 40” (total installation), 30” x 11” (each panel) ................................29 22. Influence (detail) ..........................................................................................30 23. My Mother and My Sister, 2010, Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper, 128” x 84” ...............................................................................................31 24. My Mother and My Sister (detail) ...............................................................32 25. My Mother and My Sister (detail) ................................................................33 26. My Mother and My Sister (detail) ................................................................34 27. My Mother and My Sister (detail) ................................................................35 28. Right Here, 2011, Charcoal and Acrylic Ground on Paper, 85” x 60” ..........36 29. Right Here (detail)........................................................................................37 30. Influence, Father and Son, Watching Them Both, Long History (installation view) ........................................................................................................38 31. Watching Them Both, Long History (installation view)................................39 32. Influence, Father and Son (installation view)................................................40 33. Watching Them Both, Here Together (installation view)..............................41 34. Watching Them Both, Here Together (installation view)..............................42 35. Long History, My Mother and My Sister (installation view).........................43 36. Father and Son (installation view) ...............................................................44 36. here we are. (title) (installation view) ..........................................................45 1 When I think of where I come from, it is not a place it is a community. When asked where I grew up, I give the easy answer of the name of the island versus explaining the transient nature of my childhood. To simply say I am from Bainbridge Island is true, but I do not think of the actual island or any of the seven houses in which I lived. I think of my family, the friends I grew up with, and their families. I have never lived long in any place. The only constants were the people closest to me. Even as an adult, I have never stayed anywhere long, moving every year since I was eighteen years old. The education and career path I chose encouraged or demanded a willingness and flexibility to move from location to location, opportunity to opportunity. I have grown to accept that temporality and transience are a part of my life. This itinerancy creates only temporal feelings of connection to a place. The lasting connections I establish and carry with me are with the people around me. Gathering these people together in my drawings and examining both the connections that exist between them and the relationships I have with each of them allow me to create an abstract space to which I belong. The people in the drawings do not belong to the same literal communities. Many of them do not know each other. As the linchpin, I create this community that exists only in my head and on the paper. The space in which these people communally exist in my mind is translated onto the paper, giving the viewer an intimate and honest glimpse into the ephemeral space I create for myself. The way I see the world is directly connected to how I see the people around me. The space I inhabit is created by the people in my life, and defined by the relationships I observe and engage in. The images in the drawings are of those to whom I am closely 2 connected. I am part of an abstract space which includes the various people in my community. In this space, I can bring together and make connections between people from seemingly unrelated periods of my life. I put individuals with whom I have had similar relationships together, those who have influenced me come together in an abstract space. The space is not real, or representational of any real space, but empty and dependent on those within it. The figures in my drawings represent how I interpret the associations I am a part of and how I relate to the relationships I see around me. By putting these people in the same space, I can examine and explore more effectively how I see them and how they influence me. The space is quiet, not chaotic. Each moment calm and still. The simple communication between the figures, or the obscured overlapping of shapes and people remain quiet. “There is nothing like silence to suggest a sense of unlimited space. Sounds lend color to space, and confer a sort of sound body upon it. But absence of sound leaves it quite pure, and in the silence, we are seized with the sensation of something vast and deep and boundless” (Henri Bozco, Malicroix)1. The quiet space allows simple connections between the individuals to be the focus. Each drawing shows a moment or a thought, not a whole story. There is no complicated narrative, but a short reflection or memory of something poignant. Although the focus of my work is personal and figurative, the empty areas in the drawings are an important narrative aspect. The color fields the figures reside within represent this abstracted space described earlier. Confined only by the physical edge of 1 Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1969) 43. 3 the paper, the spaces are conceptually limitless. The undefined voids the figures occupy allow them to remain projections or representations, rather than actual people. Abstracting the space around the figures by leaving it unaddressed allows the viewer to consider their own interpretations, memories and narratives in relation to the depicted image. Many pieces incorporate figures drawn larger than life. Referencing Gaston Bachelard’s idea of the “intimate immensity2”, I enlarge the figures to create the feeling of a projection, a daydream, or a thought. Adding to ideas created with the lack of landscape, larger-than-life, immensity, and grandeur all bring the images away from “every day” and imbue them with personal importance. “One might say that immensity is a philosophical category of daydream. Daydream undoubtedly feeds on all kinds of sights, but through a sort of natural inclination, it contemplates grandeur3”. This contemplation brought on by the large-scale images allows the viewer to stand back and still be surrounded by the image. Small pieces become mementos or objects to hold, like a snapshot or souvenir. Instead of projected thoughts, they are tokens that represent memories and moments. The smaller work tends to be more abstract; less of a projection and more intimate. This work does not define relationships, but one person over and over. It is the viewer’s relationship with the image that is directly addressed. Each set of smaller images connect to each other, building meaning. Either the close-up repetitious compositions of 2 3 Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1969) 183. Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1969) 183. 4 Influence or the far away isolated compositions of Away add to the intimacy or isolation, respectively. The edges of the paper hold each relationship in a frame. Sometimes the area around the figure takes over the image, and sometimes the figures fight the edges to stay seen on the paper. Bernard Tschumi, writing from an architectural philosopher’s point of view, discusses how a body entering an empty room is an act of violence, interrupting its quiet ideal state. A space, even one meant for use, is no longer pristine when entered4. In the same way that the entirety of the space is no longer intact when a body enters it, the space in the drawings is disrupted by the edges of the composition. Whether the figure is rendered miniature by the overwhelming void around them, or the edges crop out shoulders, heads and bodies from our view, the space is forcefully changed. As the artist, I get to push and pull these edges, controlling the tension and perceived violation of the space. The picture plane is cut way down in the pieces of Watching Them Both. All you can see are the torsos of the people, emphasizing the space between them. This distance between them is not awkward; the woman easily leans into the space, crossing it. These images are from a candid video of my parents at lunch one day at Diamond Lake in Oregon. Diamond Lake is a place of importance to my father, somewhere his father took him every year when he was a child. While at this place that was important to him, and was somewhat representative of his memory of his father, I caught this moment that was entirely every-day. My dad is reading an email off his phone out-loud to my mother, 4 Tschumi, Bernard. Architecture and Disjunction. (Boston, MIT, 1994) 123. 5 both pushing his history with the place aside and pulling the present relationship back into the foreground. Contained on a single piece of paper, the compositions are long and narrow. The tension between the two figures is intimate and relaxed. The drawings of my mother are often overlapped, leaning in, and sitting back, comfortably listening. (Through controlling pictorial space, use of ghost images, and overlapping figures the viewer accesses the narrative. The drawing titled My Mother and My Sister explores the intimate relationship between two people, especially the relationship between child and parent. As we age, that intimacy remains, but the familiarity may become strained. There is space between the two figures, and their eyes do not meet, but the arm of the mother reaches out to cross that space. The sole subjects of the drawing, the figures stand alone, not grounded in a specific space. The isolation creates an opening into which a viewer can interpret their own meaning. My sister stands in for me as I think about how I interact with my mother, and my mother stands in for me as a protective older sister who reaches out and holds on to the connection between us. Even though on one level this is a drawing about my mother and my sister, it is very much about me, and my relationship with both of them. The space around the figures in My Mother and My Sister, unlike Watching Them Both, weighs in on the people instead of the edges of the composition. Allowing them to be alone in a quiet moment, simply depicted, brings their shared touch into the foreground, making that contact becomes the subject of the piece, not the actual people. This touch is echoed in Father and Son, representing a relationship I only observe, but do 6 not participate in. It could be said they are in the act of bridging the gap of this abstract space separating ourselves and others. Confined on the paper, the distance between figures becomes a material thing. Tschumi asks “If space is a material thing, does it have boundaries?” If the space depicted is not the space itself, then the depiction is all that has boundaries, and the space in which these people exist is infinite. If the space on the paper is real, then it has boundaries – the edges of the paper dictating these with clean square edges. The space reaches out past the edges of the paper and intertwines with all the spaces around it. Each drawing is not an entity on its own, but a view into a section of what surrounds me. The images are projected onto the paper, but the paper is not a perfect surface. The pictorial space is broken up into sections – the edges of the paper creating rifts and breaks in the plane. The ideas are projected onto the paper, not re-created on the paper. The paper is still an object. Similar to projecting a movie onto a screen, the ideas are only re-created on the paper, their existence is not limited to the picture plane. Although none of the figures are actually drawings of me, they are all in a way selfportraits. I use the people because they are important to me personally, but also because I can project myself into the depicted relationship from all sides. The abstract space within my drawings allows me to be not in the drawing, observing the drawing, and everybody in the drawing all at once. I am not interested in drawing myself, mostly because it is unnecessary and redundant. The images communicate a sense of who these people are, not necessarily the people themselves. I project how I see myself, and my personal relationships onto these people. Carl Jung wrote that it is in our dreams that the 7 unconscious speaks to us. Dreams are not the fulfillment of repressed wishes, as Freud wrote, but, according to Jung, the voice of the “higher self”. In our dreams we are being given insight into our unconscious selves, and each person, each activity, each thing represents a part of ourselves5. In this same way, I am using the people around me to show different sides of myself. In each drawing, I look at a relationship from a different angle. At the same time, looking at myself from a different angle. In The Happiness of Architecture, Alain de Botton writes: “Belief in the significance of architecture is premised on the notion that we are, for better or for worse, different people in different places – and on the conviction that it is architecture’s task to render vivid to us who we might ideally be.”6 We project the ideal version of ourselves onto the space we inhabit. We decorate our homes, our desks, and our spaces to show others who we are. As we look to our dreams to understand our unconscious mind, I look to my relationships with others to understand the complexities of my community. In the spaces I create in my drawings, I search for who I am. 5 Weitz, Lawrence J., Ph.D. "Jung and Freud's Contributions to Dream Interpretation: A Comparison." American Journal of Psychotherepy. 30.2, 1976, 290. 6 De Botton, Alain. The Architecture of Happiness (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2006) 13. 8 WORKS CITED Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space: The classic look at how we experience intimate places. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1969. Print. De Botton, Alain. The Architecture of Happiness. 1st ed. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2006. Print. Tschumi, Bernard. Architecture and Disjunction. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1994. Print. Weitz, Lawrence J., Ph.D. "Jung and Freud's Contributions to Dream Interpretation: A Comparison." American Journal of Psychotherepy. 30.2 (1976): Print. 9 Image 1 – Father and Son 10 Image 2 – Father and Son (detail) 11 Image 3 – Father and Son (detail) 12 Image 4 – Watching Them Both 13 Image 5 – Watching Them Both (panel 1 of 4) 14 Image 6 – Watching Them Both (panel 2 of 4) 15 Image 7 – Watching Them Both (panel 3 of 4) 16 Image 8 – Watching Them Both (panel 4 of 4) 17 Image 10 – Watching Them Both (detail of panel 1 of 4) 18 Image 11 – Watching Them Both (detail of panel 3 of 4) 19 Image 9 – Watching Them Both (detail of panel 4 of 4) 20 Image 12 – Watching Them Both (installation detail) 21 Image 13 – Watching Them Both (installation detail) 22 Image 14 – Here Together 23 Image 15 – Here Together (detail) 24 Image 16 – Here Together (detail) 25 Image 17 – Here Together (detail) 26 Image 18 – Here Together (detail) 27 Image 19 – Long History 28 Image 20 – Long History (detail) 29 Image 21 – Influence 30 Image 22 – Influence (detail) 31 Image 23 – My Mother and My Sister 32 Image 24 – My Mother and My Sister (detail) 33 Image 25 – My Mother and My Sister (detail) 34 Image 26 – My Mother and My Sister (detail) 35 Image 27 – My Mother and My Sister (detail) 36 Image 28 – Right Here 37 Image 29 – Right Here (detail) 38 Image 30 - Influence, Father and Son, Watching Them Both, Long History (installation view) 39 Image 31 - Watching Them Both, Long History (installation view) 40 Image 32 – Influence, Father and Son (installation view) 41 Image 33 – Watching Them Both, Here Together (installation view) 42 Image 34 – Watching Them Both, Here Together (installation view) 43 Image 35 – Here Together, My Mother and My Sister (installation view) 44 Image 36 – Father and Son (installation view) 45 Image 37 – here we are (title) (installation view)