EASTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY

New Program Guidelines

EASTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY

D IVISION OF A CADEMIC A FFAIRS

O UTLINE FOR S UBMITTING P ROPOSALS FOR N EW D EGREE P ROGRAMS

Use this outline to prepare proposals for new programs, including undergraduate majors and minors and graduate majors.

Proposals should be submitted in narrative form, organized according to the following outline. Guidelines for submitting such proposals are on the following pages.

P

ROPOSED

P

ROGRAM

N

AME

: M

INOR IN

F

OUNDATIONS IN

S

PANISH

T

RANSLATION

D

EGREE

: B

ACHELOR OF

A

RTS WITH A

M

INOR IN

R

EQUESTED

S

TART

D

ATE WINTER

2013

F

OUNDATIONS IN

S

PANISH

T

RANSLATION

D

EPARTMENT

(

S

)/S

CHOOL

(

S

): W

ORLD LANGUAGES

C

ONTACT

P

ERSON

: Rosemary Weston-Gil

C

OLLEGE

(

S

):

ARTS

&

C

ONTACT

P

HONE

: 7-0130

SCIENCES

C

ONTACT

E

: rweston3@emich.edu

I.

Description :

General philosophy and intent of program

Translation and interpretation are intellectual activities that aim to bridge the gap between individuals and groups with different languages. The main goal of such activities is to bring people together that would otherwise remain strangers so they can communicate orally and in writing for multiple everyday and/or professional purposes. Thinking of translation and interpretation in the widest sense, it can be seen that they not only happen when different languages come into contact, but rather on any occasion when individuals or groups with different backgrounds and/or lifestyles come into contact – even if they communicate in a common language. For example, the expression “economic crisis” has different meanings for different peoples not only worldwide but also in the United States.

We are now aware that translation and interpretation are performed daily, by many of us, at different levels. As such, they quite spontaneously overflow the four walls of a classroom or the campus of a university, to find themselves at work in various settings. Extensive and intensive reflection on translation, interpretation, and service learning provide students with the professional tools needed to render the most adequate translations and interpretations. Such work is based on deep linguistic, social, cultural and educational knowledge of the source texts and on an intimate professional knowledge of the target audience (i.e. the Spanish translation of the source texts, as well as the interpretation of conversations), their social, political, cultural, educational and linguistic uses. Both these knowledge bases as well as the necessary related skills needed to be proficient will be achieved in the proposed minor in Foundations in Spanish Translation via extensive practice, both in and outside of the classroom (internships and service learning contracts will be sought for students) as they pertain to professional fields, but, especially, to those of business, education, health, and law.

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines

A.

Goals

2

The overall program goals are as follow:

• Learn to appreciate and manipulate two official languages, English and Spanish; with the option of a third language as well;

•

Gain greater understanding of the influence of culture, history and politics on language use;

•

Obtain professional training in the translation and interpretation processes with emphasis on linguistics, especially contrastive grammar, semantics, phonology, strategies and technologies;

• Work creatively and professionally in internships, private contracts, once students complete the minor;

•

Be able to work in a “portable” (computers allow and promote this all over the world).

B. Objectives

The program and all courses will seek to enable students to:

• Explore and understand the details, nuances, and secrets of language and language transfer;

•

Understand the theories, workings, processes, and importance of translation/interpretation, and the translator/interpreter, in all international and intercultural exchanges;

• Learn about and develop the skills, terminology and technologies of T&I, as well as the related linguistic fields of semantics, phonology, transformational grammar, etc., especially from a comparative perspective crucial to translate and interpret effectively and successfully

•

Undertake the practical activities of translators and interpreters, especially through various oral and written exercises, simulations, use of electronic media as well as human intervention

•

Participate and work in increasing international inter-connectedness to acquire professional skills in language transfer and get a job in the field;

• Work as a translator, or interpreter, or terminologist, or reviser, or bilingual, and even trilingual editor/writer – in the U.S., or internationally via internships, such as those offered by the government, companies, non-profit institutions, and courts (e.g. interpreting)

C.

Student Learning Outcomes

Students should be able to undertake the following successfully:

•

Analyze a source speech or text for translation and interpretation, including the identification of meaning, stylistics, register, and emotional tone while applying the concepts of linguistic and cultural translatability and untranslatability, cultural and functional equivalency, and types of meaning (i.e., propositional meaning, expressive meaning, presupposed meaning, and evoked meaning)

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines 3

• Conduct research relevant to performing specific translation and interpretation assignments and design an industry-standard terminology database to store and maintain results

• Demonstrate effective note-taking for consecutive interpretation

•

Perform professional translation and interpretation at real-life speeds in a variety of fields, situations, and modes (i.e., consecutive and simultaneous interpretation, sight translation)

•

Implement performance improvements based on professional and self-evaluation of practical translation and interpretation experience

•

•

•

•

Use a range of fundamental equipment and software needed to begin work as a translator or interpreter

Develop and employ essential industry-oriented business materials, including résumés, business cards, portfolios, contractual agreements, and invoices

Describe the different types and levels of certification available to interpreters and the legal requirements to work as an independent contractor in the State of Michigan

Apply a variety of codes of ethics for translators and interpreters, including the concepts of impartiality, confidentiality, and conflict of interest

B.

Program

1.

List of current courses included for Translation/Interpretation minor:

Required Courses (12 credits)

SPNH 420 Introduction to Translation

SPNH 430 Spanish Phonetics and Phonology

SPNH 443 Advanced Spanish Grammar and Composition

3-hours course at the 400-level with Spanish section approval

Restricted electives

SPNH 411 Cultures of Spain

SPNH 412 Cultures of Spanish America

SPNH 422 Hispanic Linguistics

SPNH 444 Advanced Spanish Conversation and Composition

SPNH 490 Intensive Spanish (6 credits)

2.

List of new courses included for the Spanish Translation minor:

SPNH 466 Introduction to Spanish Interpretation

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines

3.

Program Delivery Plan:

4

For the present, all classes will be offered on campus and in the evening to attract not only campus students but also those who live and work outside the campus. In the future, some classes may be offered on line, especially those of translation.

4.

Outline of typical program of study student would follow to complete the T&I minor

FALL SEMESTER :

SPNH 443 Advanced Spanish Grammar and Composition

SPNH 430 Spanish Phonetics and Phonology

WINTER SEMESTER :

NEW COURSE: SPNH 466 Introduction to Spanish Interpretation

SPNH 422 Hispanic Linguistics

SUMMER SEMESTERS:

SPNH 420 Introduction to Translation

SPNH 444 Advanced Spanish Conversation and Composition

FALL SEMESTER :

SPNH 412 The Cultures of Spain

5.

Undergraduate program

A student would need to complete at least 21 hours or all the courses required for the minor in order to graduate. Some students may need additional classes depending on their level of proficiency and accuracy at the time they declared the minor in Translation & Interpretation.

C.

Admission

In addition to being passionate about and good at English and Spanish, interested in other languages and curious about and knowledgeable of current affairs, arts, history, literature, culture; as well as interested in reading, writing, and all aspects of language use, students should have:

1.

Completed the following or equivalent classes:

Spanish 343 Spanish Grammar & Composition

Spanish 344 Spanish Conversation & Composition

2.

Have achieved an overall B average or 3.0 GPA, in all Spanish classes taken prior to or after admission or at least a score of 500 on the Spanish Placement test. If a student has not taken

Spanish for a year or has received a score of less than 500 on the Spanish Placement, s/he may be asked, to take certain courses as part of a conditional admission in which the student must receive a <<B>> average.

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines

D.

Projections

1.

Number of students at initial enrollment

5

One of the classes proposed as part of the Spanish Translation & Interpretation minor —and offered for the past several years—Introduction to Translation—English/Spanish,

Spanish/English— has attracted, on average, 15 to 20 students per semester. If approved the minor is expected to attract at least that number but, eventually, more, once the program gains momentum.

2.

Scheduling needs and patterns for the next three to five years:

FALL SEMESTERS:

SPNH 411 Cultures of Spain

SPNH 430 Spanish Phonetics and Phonology

SPNH 443 Advanced Spanish Grammar and Composition

WINTER SEMESTERS:

SPNH 412 Cultures of Spanish America

SPNH 422 Hispanic Linguistics

SPNH 444 Advanced Spanish Conversation and Composition

NEW COURSE: SPNH 466 Introduction to Spanish Interpretation

SUMMER SEMESTERS:

SPNH 420 Introduction to Translation

SPNH 443 Advanced Spanish Grammar and Composition

SPNH 444 Advanced Spanish Conversation and Composition

SPNH 479 Special Topics: Variable Topic in Translation

SPNH 490 Intensive Spanish (6 credits)

II. Justification/Rationale

A.

Demand for Program

Translation and interpretation are very desirable foreign language skills for today’s college students and as their use in numerous professional fields, especially, those of international business, health, law, and science, attest. Newspaper and other printed and electronic articles abound showing the increasing need for professionals with these capabilities.

B.

Similar programs in Michigan

In Michigan, only one college offers a translation program: Mary Grove College. It is not a state university but a private one and, unlike the EMU I&T program, it focuses on literary translation. It does not include interpretation and does not focus on the professional fields to be addressed in the

EMU T&I program, namely business, education, health, and law. Consequently, EMU is wellpositioned to gain stature and fame in an area that has been ignored by practitioners, particularly by

World Language Departments. Indeed, students, who have taken existing translation classes at EMU

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines 6 have inquired and insisted that they be offered a course in Interpretation to complement their writing knowledge and, thus, become more marketable and useful in the profession they are pursuing. That

Interpretation is being added to the minor not only makes the latter unique but also reflects the fact that Spanish is the third most spoken language in the world, as well as the first in the America’s (the second in the U.S.), with more than half billion people speaking it, whose importance goes beyond mere local needs but extends to those of a global nature.

C.

Evidence of support for the proposed program from within and outside the University

See attached letter from the Department Head of World Languages in support of the new proposed

Minor in Foundations in Spanish Translation (Appendix A)

D.

Additional justification

•

A copy of the report done by the U.S. Department of Labor in its annual publication Occupation

Handbook on the fields of Translation & Interpretation is included in Appendix B. The report provides further and valuable information and statistics on the current and future status of T&I with regard to the following topics:

Nature of the Work

•

Training, Other Qualifications, and Advancement

•

Employment

•

•

Job Outlook

Projections

•

•

Earnings

Wages

•

Related Occupations

•

Sources of Additional Information

III Preparedness

A Names and qualifications of the faculty involved in the T&I minor (Brief CVs for each of the faculty members listed below are included in Appendix C)

1.

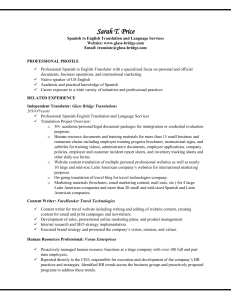

Ronald Cere (Ph. D, New York University).

Created and taught the Introduction to Spanish Translation & Interpretation course offered at

EMU since 2000. Prepared course pack, as well as all instructional (electronic and printed) materials which focus on professional areas, such as business, education, health, and law. Dr.

Cere has also translated scores of documents in French and Spanish (birth certificates, driver’s license, marriage certificates, etc) for individuals as well as Fortune 500 companies (Pfizer,

MASCO, etc.), government agencies, and non-profits (The Corner Health Center, Ypsilanti, MI).

(See in Appendix C for a brief resume)

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines 7

2.

Alfonso Illingworth-Rico (Ph. D. University of Arizona)

Former adviser of the Bilingual/Bicultural Teacher Education Program at EMU. His research has focused on bilingualism and language choice in U. S. Hispanic writers. Worked as translator for ATP Consulting from Ann Arbor, Michigan; the Suárez-Clausen/ Piqué Consulting Firm from

Buenos Aires, Argentina; CMS Energy from Jackson Michigan; and the Thomson-Heinle

Publishing Co. He has also served as volunteer translator/interpreter for the Community Action

Agency from Michigan; Michigan Secretary of State, and Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti legal courts.

(See in Appendix C for a brief resume)

3.

Monica Millan (Ph. D, University of Illinois at UC).

Created and taught the Hispanic Linguistics and Phonetic and Phonology courses at EMU and at the University of Illinois at UC. Dr. Millán specializes in Spanish Linguistics, more specifically

Sociolinguistics and Language Variation. Dr. Millán also worked in the past translating documents in Spanish and English (business correspondence, user guides, technical manuals, etc.) for two companies in Colombia. (See in Appendix C for a brief resume)

B. Current and future status of library holdings

1. At present, in addition to various bilingual, general, and specialized dictionaries, there are some theoretical and practical texts in the library on translation and interpretation which have been used in the already offered Introduction to Spanish Translation & Interpretation course

2. For the new minor, new specialized dictionaries and reference texts will be needed. Also with research and developments in the field of T & I constantly occurring every year, new electronic and multimedia resources will be needed. These materials may be acquired through the departmental normal request for books and other instructional materials, but additional university funds will need to be sought.

C. Existing instructional facilities:

Increased use of the Alexander Music computer laboratory and facilities in Hall Library will probably be needed, especially for oral and written practice

D. Adequacy of Support beyond the Department

No additional support services are anticipated at this time except for those mentioned in B and C a bove.

E.

Plan for Marketing the proposed program and recruiting students into it

Flyers, pamphlets and announcements in such venues of the EASTERN ECHO, as well as the

Department of World Languages website, describing the T&I program and its academic and practical benefits, will be created. Attending MITIN (Michigan Translators & Interpreters Network) to recruit beginning professionals in the field. Informing students during events, such as Explore

Eastern.

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines

IV. Assessment/Evaluation

A.

Plan and schedule for assessing the quality of program

The plan will include written measurable and scaled instruments which will ascertain the following: a.

Realization of program goals, objectives, and student learning outcomes b. Surveys conducted by faculty to help evaluate program c.

Student and other evaluation forms, including letters and related pertinent documents d. Grants that may provide an evaluation by an outside accredited agency (American

Association of Translators and Interpreters

B.

Schedule for assessing the program

The assessment will be undertaken after a sufficient number of the courses of the Spanish

Translation & Interpretation minor (at least half of them) have been offered

V. Program Costs

8

For the present and near future, no new personnel, facilities, nor equipment except for one or two new computers with special capabilities for students to undertake certain translation and nterpretation exercises and resources (e.g., books, journals, etc.) will be needed

VI. Action of the Department/College

1. Department/School (Include the faculty votes signatures from all submitting departments/schools.)

Vote of faculty: For 17 Against 0

(Enter the number of votes cast in each category.)

I support this proposal. The proposed program can X cannot additional College or University resources.

Abstentions 0

be implemented without

Rosemary Weston-Gil

Department Head/School Director Signature

5/2/12

Date

2. College/Graduate School ( Include signatures from the deans of all submitting colleges.)

A. College .

I support this proposal. The proposed program can cannot the affected College without additional University resources.

College Dean Signature

B. Graduate School (new graduate programs ONLY)

Graduate Dean Signature

be implemented within

Date

Date

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines

VII. Approval

Associate Vice-President for Academic Programming Signature

VIII. Appendices

Date

9

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines

APPENDIX B

US Department of Labor

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2010-11 Edition

10

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Interpreters and Translators

•

Nature of the Work

•

•

Training, Other Qualifications, and Advancement

Employment

OOH Home

Index

•

Job Outlook

OVERVIEW OF

THE 2008-18

PROJECTIONS

Management

Professional

Service

Sales

Administrative

•

•

Projections

Earnings

•

Wages

•

Related Occupations

•

Sources of Additional Information

Significant Points

•

About 26 percent of interpreters and translators are self-employed; many freelance and work in this occupation only sporadically.

Farming

Construction

Installation

•

•

In addition to needing fluency in at least two languages, many interpreters and translators need a bachelor's degree.

Employment is expected to grow much faster than average.

Production •

Job prospects vary by specialty and language.

Transportation

Armed Forces

Special Features

Nature of the Work

Interpreters and translators facilitate the cross-cultural communication necessary in today's society by converting one language into another. However, these language specialists do more than simply translate words—they relay

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines 11 concepts and ideas between languages. They must thoroughly understand the subject matter in which they work in order to accurately convey information from one language into another. In addition, they must be sensitive to the cultures associated with their languages of expertise.

Although some people do both, interpreting and translation are different professions. Interpreters deal with spoken words, translators with written words. Each task requires a distinct set of skills and aptitudes, and most people are better suited for one or the other. While interpreters often interpret into and from both languages, translators generally translate only into their native language.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Interpreters convert one spoken language into another—or, in the case of signlanguage interpreters, between spoken communication and sign language.

Interpreting requires that one pay attention carefully, understand what is communicated in both languages, and express thoughts and ideas clearly.

Strong research and analytical skills, mental dexterity, and an exceptional memory also are important.

RELATED LINKS:

OOH REPRINTS

There are two modes of interpreting: simultaneous, and consecutive.

Simultaneous interpreting requires interpreters to listen and speak (or sign) at

HOW TO ORDER

A COPY the same time someone is speaking or signing. Ideally, simultaneous interpreters should be so familiar with a subject that they are able to anticipate the end of the speaker's sentence. Because they need a high degree of

TEACHER'S

GUIDE concentration, simultaneous interpreters work in pairs, with each interpreting for 20-minute to 30-minute periods. This type of interpreting is required at international conferences and is sometimes used in the courts.

OOH FAQS

LINKS:

ADDITIONAL

CAREER GUIDE

TO INDUSTRIES

In contrast to the immediacy of simultaneous interpreting, consecutive interpreting begins only after the speaker has verbalized a group of words or sentences. Consecutive interpreters often take notes while listening to the speakers, so they must develop some type of note-taking or shorthand system.

This form of interpreting is used most often for person-to-person communication, during which the interpreter is positioned near both parties.

CAREER

ARTICLES FROM

THE OOQ

Translators convert written materials from one language into another. They must have excellent writing and analytical ability, and because the translations that they produce must be accurate, they also need good editing skills.

EMPLOYMENT

PROJECTIONS

Translating involves more than replacing a word with its equivalent in another language; sentences and ideas must be manipulated to flow with the same coherence as those in the source document so that the translation reads as though it originated in the target language. Translators also must bear in mind any cultural references that may need to be explained to the intended audience, such as colloquialisms, slang, and other expressions that do not translate literally. Some subjects may be more difficult than others to translate because words or passages may have multiple meanings that make several translations possible. Not surprisingly, translated work often goes through multiple revisions before final text is submitted.

Nearly all translation work is done on a computer, and most assignments are

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

12 received and submitted electronically. This enables translators to work from almost anywhere, and a large percentage of them work from home. The Internet provides advanced research capabilities and valuable language resources, such as specialized dictionaries and glossaries. In some cases, use of computerassisted translation—including memory tools that provide comparisons of previous translations with current work—helps save time and reduce repetition.

The services of interpreters and translators are needed in a number of subject areas. While these workers may not completely specialize in a particular field or industry, many do focus on one area of expertise. Some of the most common areas are described below; however, interpreters and translators may work in a variety of other areas also, including business, education, social services, and entertainment.

Judiciary interpreters and translators facilitate communication for people with limited English proficiency who find it challenging to communicate in a legal setting. Legal translators must be thoroughly familiar with the language and functions of the U.S. judicial system, as well as other countries' legal systems.

Court interpreters work in a variety of legal settings, such as attorney-client meetings, preliminary hearings, arraignments, depositions, and trials. Success as a court interpreter requires an understanding of both legal terminology and colloquial language. In addition to interpreting what is said, court interpreters also may be required to read written documents aloud in a language other than that in which they were written, a task known as sight translation.

Medical interpreters and translator, sometimes referred to as healthcare interpreters and translators , provide language services to healthcare patients with limited English proficiency. Medical interpreters help patients to communicate with doctors, nurses, and other medical staff. Translators working in this specialty primarily convert patient materials and informational brochures issued by hospitals and medical facilities into the desired language. Interpreters in this field need a strong grasp of medical and colloquial terminology in both languages, along with cultural sensitivity to help the patient receive the information.

Sign-language interpreters facilitate communication between people who are deaf or hard of hearing and people who can hear. Sign-language interpreters must be fluent in English and in American Sign Language (ASL), which combines signing, finger spelling, and specific body language. Most signlanguage interpreters either interpret, aiding communication between English and ASL, or transliterate, facilitating communication between English and contact signing—a form of signing that uses a more English language-based word order. Some interpreters specialize in oral interpreting for people who are deaf or hard of hearing and lip-read instead of sign. Other specialties include tactile signing, which is interpreting for people who are blind as well as deaf by making manual signs into their hands, using cued speech, and signing exact

English.

Conference interpreters work at conferences that have non-English-speaking attendees. The work is often in the field of international business or diplomacy,

New Program Guidelines 13 although conference interpreters can interpret for any organization that works with speakers of foreign languages. Employers prefer high-level interpreters who have the ability to translate from at least two languages into one native language—for example, the ability to interpret from Spanish and French into

English. For some positions, such as those with the United Nations, this qualification is mandatory.

Guide or escort interpreters accompany either U.S. visitors abroad or foreign visitors in the United States to ensure that they are able to communicate during their stay. These specialists interpret on a variety of subjects, both on an informal basis and on a professional level. Most of their interpreting is consecutive, and work is generally shared by two interpreters when the assignment requires more than an 8-hour day. Frequent travel, often for days or weeks at a time, is common, and it is an aspect of the job that some find particularly appealing.

Literary translators adapt written literature from one language into another.

They may translate any number of documents, including journal articles, books, poetry, and short stories. Literary translation is related to creative writing; literary translators must create a new text in the target language that reproduces the content and style of the original. Whenever possible, literary translators work closely with authors to best capture their intended meanings and literary characteristics.

Localization translators completely adapt a product or service for use in a different language and culture. The goal of these specialists is to make it appear as though a product originated in the country where it will be sold and supported. At its earlier stages, this work dealt primarily with software localization, but the specialty has expanded to include the adaptation of Internet sites, marketing, publications, and products and services in manufacturing and other business sectors.

Work environment. Interpreters work in a wide variety of settings, such as schools, hospitals, courtrooms, and conference centers. Translators usually work alone, and they must frequently perform under pressure of deadlines and tight schedules. Technology allows translators to work from almost anywhere, and many choose to work from home.

Because many interpreters and translators freelance, their schedules often vary, with periods of limited work interspersed with periods requiring long, irregular hours. For those who freelance, a significant amount of time must be dedicated to looking for jobs. Interpreters who work over the telephone or through videoconferencing generally work in call centers in urban areas and keep to a standard 5-day, 40-hour workweek.

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines 14

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

Interpreters and translators must have a thorough understanding of various languages.

Training, Other Qualifications, and Advancement

Interpreters and translators must be fluent in at least two languages. Their educational backgrounds may vary widely, but many need a bachelor's degree.

Many also complete job-specific training programs.

Education and training. The educational backgrounds of interpreters and translators vary. Knowing at least two languages is essential. Although it is not necessary to have been raised bilingual to succeed, many interpreters and translators grew up speaking two languages.

In high school, students can prepare for these careers by taking a broad range of courses that include English writing and comprehension, foreign languages, and basic computer proficiency. Other helpful pursuits include spending time abroad, engaging in direct contact with foreign cultures, and reading extensively on a variety of subjects in English and at least one other language.

Beyond high school, there are many educational options. Although a bachelor's degree is often required for jobs, majoring in a language is not always necessary. An educational background in a particular field of study can provide a natural area of subject-matter expertise. However, specialized training in how to do the work is generally required. Formal programs in interpreting and translation are available at colleges nationwide and through nonuniversity training programs, conferences, and courses. Many people who work as conference interpreters or in more technical areas—such as localization, engineering, or finance—have master's degrees, while those working in the community as court or medical interpreters or translators are more likely to complete job-specific training programs.

Other qualifications. Experience is an essential part of a successful career in either interpreting or translation. In fact, many agencies or companies use only the services of people who have worked in the field for 3 to 5 years or who

New Program Guidelines

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

15 have a degree in translation studies, or both.

A good way for translators to learn firsthand about the profession is to start out working in-house for a translation company; however, such jobs are not very numerous. People seeking to enter interpreter or translator jobs should begin by getting experience whatever way possible—even if it means doing informal or volunteer work.

Volunteer opportunities are available through community organizations, hospitals, and sporting events, such as marathons, that involve international competitors. The American Translators Association works with the Red Cross to provide volunteer interpreters in crisis situations. Any translation can be used as an example for potential clients, even translation done as practice.

Paid or unpaid internships and apprenticeships are other ways for interpreters and translators to get started. Escort interpreting may offer an opportunity for inexperienced candidates to work alongside a more seasoned interpreter.

Interpreters might also find it easier to break into areas with particularly high demand for language services, such as court or medical interpreting.

Whatever path of entry they pursue, new interpreters and translators should establish mentoring relationships to build their skills, confidence, and professional network. Mentoring may be formal, such as through a professional association, or informal with a coworker or an acquaintance who has experience as an interpreter or translator. Both the American Translators

Association and the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf offer formal mentoring programs.

Translators working in localization need a solid grasp of the languages to be translated, a thorough understanding of technical concepts and vocabulary, and a high degree of knowledge about the intended target audience or users of the product. Because software often is involved, it is not uncommon for people who work in this area of translation to have a strong background in computer science or to have computer-related work experience.

Self-employed and freelance interpreters and translators need general business skills to successfully manage their finances and careers. They must set prices for their work, bill customers, keep financial records, and market their services to attract new business and build their client base.

Certification and advancement. There is currently no universal form of certification required of interpreters and translators in the United States.

However there are a variety of different tests that workers can take to demonstrate proficiency, which may be helpful in gaining employment. For example, the American Translators Association provides certification in 24 language combinations involving English for its members.

Federal courts have certification for Spanish, Navajo, and Haitian Creole interpreters, and many State and municipal courts offer their own forms of certification. The National Association of Judiciary Interpreters and Translators also offers certification for court interpreting.

New Program Guidelines

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

16

The U.S. Department of State has a three-test series for prospective interpreters—one test in simple consecutive interpreting (for escort work), another in simultaneous interpreting (for court or seminar work), and a third in conference-level interpreting (for international conferences)—as well as a test for prospective translators. These tests are not considered a credential, but successful completion indicates that a person has a significant level of skill in the field. Additionally, the International Association of Conference Interpreters offers certification for conference interpreters

The National Association of the Deaf and the Registry of Interpreters for the

Deaf (RID) jointly offer certification for general sign interpreters. In addition, the registry offers specialty tests in legal interpreting, speech reading, and deafto-deaf interpreting—which includes interpreting among deaf speakers with different native languages and from ASL to tactile signing.

Once interpreters and translators have gained sufficient experience, they may then move up to more difficult or prestigious assignments, may seek certification, may be given editorial responsibility, or may eventually manage or start a translation agency.

Many self-employed interpreters and translators start businesses by submitting resumes and samples to many different translation and interpreting agencies and then wait to be contacted when an agency matches their skills with a job.

Work is often acquired by word of mouth or through referrals from existing clients.

Employment

Interpreters and translators held about 50,900 jobs in 2008. However, the actual number of interpreters and translators is probably significantly higher because many work in the occupation only sporadically. Interpreters and translators are employed in a variety of industries, reflecting the diversity of employment options in the field. About 28 percent worked in public and private educational institutions, such as schools, colleges, and universities. About 13 percent worked in healthcare and social assistance, many of whom worked for hospitals. Another 9 percent worked in other areas of government, such as

Federal, State, and local courts. Other employers of interpreters and translators include interpreting and translation agencies, publishing companies, telephone companies, and airlines.

About 26 percent of interpreters and translators are self-employed. Many who freelance in the occupation work only part time, relying on other sources of income to supplement earnings from interpreting or translation.

Job Outlook

Interpreters and translators can expect much faster than average employment growth. Job prospects vary by specialty and language.

Employment change. Employment of interpreters and translators is projected to increase 22 percent over the 2008–18 decade, which is much faster than the

New Program Guidelines

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

17 average for all occupations. Higher demand for interpreters and translators results directly from the broadening of international ties and the large increases in the number of non-English speaking people in the United States. Both of these trends are expected to continue throughout the projections period, contributing to relatively rapid growth in the number of jobs for interpreters and translators across all industries in the economy.

Demand will remain strong for translators of frequently translated languages, such as Portuguese, French, Italian, German, and Spanish. Demand should also be strong for translators of Arabic and other Middle Eastern languages and for the principal East Asian languages—Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. Demand for American Sign Language interpreters will grow rapidly, driven by the increasing use of video relay services, which allow individuals to conduct video calls using a sign language interpreter over an Internet connection.

Technology has made the work of interpreters and translators easier. However, technology is not likely to have a negative impact on employment of interpreters and translators because such innovations are incapable of producing work comparable with work produced by these professionals.

Job prospects. Urban areas, especially Washington, DC, New York, and cities in California, provide the largest numbers of employment possibilities, especially for interpreters; however, as the immigrant population spreads into more rural areas, jobs in smaller communities will become more widely available.

Job prospects for interpreters and translators vary by specialty and language.

For example, interpreters and translators of Spanish should have good job opportunities because of expected increases in the Hispanic population in the

United States. Demand is expected to be strong for interpreters and translators specializing in healthcare and law because it is critical that information be fully understood among all parties in these areas. Additionally, there should be demand for specialists in localization, driven by the globalization of business and the expansion of the Internet; however, demand may be dampened somewhat by outsourcing of localization work to other countries. Given the shortage of interpreters and translators meeting the desired skill level of employers, interpreters for the deaf will continue to have favorable employment prospects. On the other hand, competition can be expected for both conference interpreter and literary translator positions because of the small number of job opportunities in these specialties.

Projections Data

Projections data from the National Employment Matrix

Occupational

Title

SOC

Code

Employment,

2008

Projected

Employment,

2018

Change,

2008-18

Number Percent

Detailed

Statistics

Interpreters and

27-

3091

50,900 62,200 11,300 22 [ PDF ] [ XLS ]

New Program Guidelines

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

18 translators

NOTE: Data in this table are rounded. See the discussion of the employment projections table in the Handbook introductory chapter on Occupational

Information Included in the Handbook .

Earnings

Wage and salary interpreters and translators had median annual wages of

$38,850 in May 2008. The middle 50 percent earned between $28,940 and

$52,240. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $22,170, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $69,190. Individuals classified as language specialists in the Federal Government earned an average of $79,865 annually in March

2009.

Earnings depend on language, subject matter, skill, experience, education, certification, and type of employer, and salaries of interpreters and translators can vary widely. Interpreters and translators who know languages for which there is a greater demand, or which relatively few people can translate, often have higher earnings, as do those who perform services requiring a high level of skill, such as conference interpreters.

For those who are not salaried, earnings typically fluctuate, depending on the availability of work. Freelance interpreters usually earn an hourly rate, whereas translators who freelance typically earn a rate per word or per hour.

For the latest wage information:

The above wage data are from the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) survey program, unless otherwise noted. For the latest National, State, and local earnings data, visit the following pages:

· interpreters and translators

Related Occupations

Interpreters and translators use their multilingual skills, as do teachers of languages. These include:

Teachers—adult literacy and remedial education

Teachers—kindergarten, elementary, middle, and secondary

Teachers—postsecondary

Teachers—self-enrichment education

Teachers—special education

Translators prepare texts for publication or dissemination; other workers involved in this process include:

Authors, writers, and editors

New Program Guidelines

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

19

Interpreters or translators working in a legal or healthcare environment are required to have a knowledge of terms and concepts that is similar to that of other workers in these fields, such as:

Court reporters

Medical transcriptionists

Sources of Additional Information

Disclaimer:

Links to non-BLS Internet sites are provided for your convenience and do not constitute an endorsement.

Organizations dedicated to these professions can provide valuable advice and guidance to people interested in learning more about interpreting and translation. The language services division of local hospitals or courthouses also may have information about available opportunities.

For general career information, contact:

•

American Translators Association, 225 Reinekers Ln., Suite 590,

Alexandria, VA 22314. Internet: http://www.atanet.org

For more detailed information by specialty, contact the association affiliated with the subject area in question. See, for example, the following:

•

•

American Literary Translators Association, University of Texas at

Dallas, 800 W. Campbell Rd., Mail Station JO51, Richardson, TX

75080-3021. Internet: http://www.utdallas.edu/alta

International Medical Interpreters Association, 800 Washington Street,

Box 271, Boston, MA 02111-1845. Internet: http://www.imiaweb.org

•

Localization Industry Standards Association, Domaine en Prael, CH-

1323 Romainmôtier, Switzerland. Internet: http://www.lisa.org

•

•

National Association of Judiciary Interpreters and Translators, 1707 L

St. NW., Suite 570, Washington, DC 20036. Internet: http://www.najit.org

National Council on Interpreting in Health Care, 5505 Connecticut Ave.

NW., Suite 119, Washington, DC 20015. Internet: http://www.ncihc.org

•

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 333 Commerce St., Alexandria,

VA 22314. Internet: http://www.rid.org

For information about testing to become a contract interpreter or translator with the U.S. State Department, contact:

•

U.S. Department of State, Office of Language Services, 2401 E St.

New Program Guidelines

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

20

NW., SA-1, Room H1400, Washington, DC 20522. Internet: http://languageservices.state.gov

Information on obtaining a position as an interpreter and translator with the

Federal Government is available from the Office of Personnel Management through USAJOBS, the Federal Government's official employment information system. This resource for locating and applying for job opportunities can be accessed through the Internet at http://www.usajobs.opm.gov

or through an interactive voice response telephone system at (703) 724–1850 or TDD (978)

461–8404. These numbers are not toll free, and charges may result. For advice on how to find and apply for Federal jobs, see the Occupational Outlook

Quarterly article “How to get a job in the Federal Government,” online at http://www.bls.gov/opub/ooq/2004/summer/art01.pdf

.

Suggested citation: Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor,

Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2010-11 Edition , Interpreters and

Translators, on the Internet at http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos175.htm

(visited

December 05, 2011 ).

Last Modified Date: July 21, 2010

New Program Guidelines 21

APPENDIX C

(Curricula vita of Program and Instructional Staff)

The names and c-vs of the EMU World Language faculty who will mediate the Translation & Interpretation minor follow. All are experienced teachers of Spanish language and culture and most have taught and done professional and scholarly work in various aspects and areas of translation and interpretation.

Ronald Cere

• Ph.D., ( cum laude ) Romance Languages (1974), Graduate Certificate of Business (1982), New York

University

• Pro. Of Span; taught courses of Translation and Interpretation, English-Spanish/Spanish-English at EMU

2000-present, as well as courses of Business Spanish, Spanish for the Health & Human Resource

Professionals

• Served as interpreter and translator

• 200 presentations, workshops on translation, interpretation, business language, diversity training, program

& curriculum development, intercultural communication, at national and international conferences

(SIETAR, ASTD, MLA, ACTFL, AATSP, SCOLT, CENTRAL STATES FL, etc.),

• Seminars on subjects above at various U.S. and international universities (U. of Maryland, North and

South Carolina, Ohio, Texas, Babson College, the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México,

Guadalajara)

• Business language and cross-cultural communication consultant & trainer for Fortune 100 companies

(MASCO, MEXICAN INDUSTRIES, PFIZER, etc.).

• Invited by Spanish government to help promote study abroad programs between Spain and the U.S.

• Co-authored several books, including the internationally renown business Spanish text program, Éxito comercial , 5 th ed. Cengage, 2011).

• Authored numerous books, articles and reviews for various publishers, notably Tools and Activities for a

Diverse Workforce (New York, McGraw-Hill, 1996), as well as studies and critiques for various professional journals ( Canadian Modern Language Journal, Hispania, Journal on Language and

International Business , Dimensions, Journal of International Business, etc.

).

• Dr. Cere is fluent in several languages (French Italian Spanish, and Portuguese), and is cited in Who’s Who in America, in the World, in American Education,

• Fellow of International Biographical Center, Cambridge, England, 1995-present

• Deputy Governor of the Am. Biog. Institute of Rsch. Assocs., 1995-present

• Professor of Spanish, former coordinator of graduate & undergraduate Language and International Trade programs

• Director, Career Services of the Am. Assoc. of Tchrs. of Span. & Port. (National, 1990-2000)

• Certificate of International Recognition, awarded by the Centers of International Business, Education &

Research (consortia of 36 U.S. research-universities actively engaged in international business, education, and research in the U.S.), in conjunction with other award to EMU (particularly the Dept. of World

Languages and College of Business for outstanding contributions, service and scholarly activity in and to the field of business language and communication, April 2008 (cited in EMU Case Notes and Focus,

Spring 2008).

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines 22

Alfonso Illingworth-Rico

• PhD. in Spanish. University of Arizona, 1994. Major field of concentration: Generalist in Spanish Letters

•

Minor field: Hispanic Linguistics

• Nominated Area Coordinator by the National Association of Hispanic and Latino Studies, 2001

•

Academic Committee President South Arbor Academy Charter School, 2001-2004

•

Excellence in Teaching Award. The University of Arizona, 1994

•

Who's Who Among America's Teachers 1998 and 2000.

•

Eastern Michigan University Foundation Faculty Excellence Award, 1999.

• Nominated for Award for Outstanding Student Support. Eastern Michigan University,2005.

• Advisor/ Recruiter, Bilingual-Bicultural Teacher Education Program. Department of Foreign Languages and

Bilingual Studies. Eastern Michigan University. 1994- present

•

Head, Spanish Section. Department of Foreign Languages and Bilingual Studies. Eastern Michigan

University, 1998- 2001

• Coordinator, Spanish Section. Department of World Languages. Eastern Michigan University, 2010- 2012

•

Advisor, Spanish Club. Eastern Michigan University, 1999-2000 2005-present

• Translator, ATP Consulting. Ann Arbor, Michigan

• Translator, PIQUE-SUAREZ-CLAUSEN Consulting Buenos Aires, Argentina.

• Translator/Intercultural Trainer. MS Energy. Jackson, Michigan.

•

Translator, Thomson-Heinle Publishing Co.

Mónica Millán

•

Ph.D. in Spanish (concentration Hispanic Linguistics), University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,

Urbana, IL. 2011.

•

Minor Field: Second Language Acquisition Teaching Education

• Assistant Professor, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI, 2009 – Present. Teach all levels of

Spanish graduate and undergraduate courses.

•

Coordinator of 100 & 200-level Spanish Courses. Department of World Languages. Eastern Michigan

University, 2010- present

•

Advisor, Spanish Graduate students. Eastern Michigan University, 2010-present.

•

Advisor, Sigma Delta Pi (Spanish Honor Society). Eastern Michigan University, 2011-present.

• Nominated for the Teaching Excellence Award. Eastern Michigan University, 2012.

• Spanish instructor and Graduate Teaching assistant at varies American Universities. Taught all levels of undergraduate Spanish courses, including Hispanic Linguistics and Spanish Phonetics & Phonology.

• Worked as translator for two Colombian companies. Translated different kinds of documents in Spanish and English.

• Presented at several Linguistics and Sociolinguistics conferences nationally and internationally.

• Reviewed a manuscript that appeared in “Spanish at the turn of the 21 st

Cultural studies in honor of LSU’s 150 th Anniversary.” 2011

century: Literary, Linguistic and

•

Dr. Millán is fluent in Spanish and English and has reading knowledge of French.

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09

New Program Guidelines 23

Miller, New Program Guidelines

Sept. 09